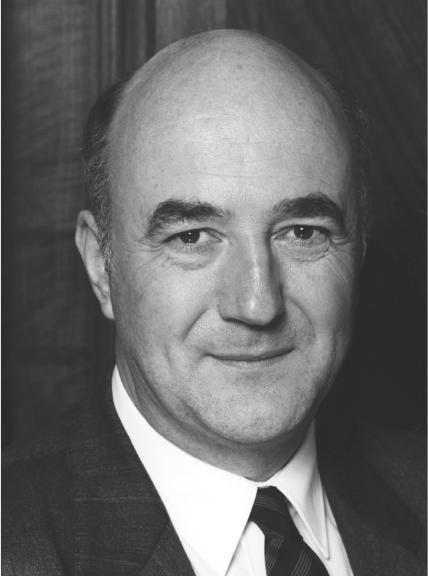

WorldEnergyOutlook2023INTERNATIONALENERGYAGENCYTheIEAexaminestheIEAmemberIEAassociationfullspectrumcountries:countries:ofenergyissuesincludingoil,gasAustraliaArgentinaandcoalsupplyandAustriaBrazildemand,renewableBelgiumChinaenergytechnologies,CanadaEgyptelectricitymarkets,CzechRepublicIndiaenergyefficiency,DenmarkIndonesiaaccesstoenergy,EstoniaKenyademandsideFinlandMoroccomanagementandFranceSenegalmuchmore.ThroughGermanySingaporeitswork,theIEAGreeceSouthAfricaadvocatespoliciesHungaryThailandthatwillenhancetheIrelandUkrainereliability,affordabilityItalyandsustainabilityofJapanenergyinitsKorea31membercountries,Lithuania13associationLuxembourgcountriesandMexicobeyond.NetherlandsNewZealandPleasenotethatthisNorwaypublicationissubjecttoPolandspecificrestrictionsthatlimitPortugalitsuseanddistribution.TheSlovakRepublictermsandconditionsareSpainavailableonlineatSwedenwww.iea.org/termsSwitzerlandRepublicofTürkiyeThispublicationandanyUnitedKingdommapincludedhereinareUnitedStateswithoutprejudicetothestatusoforsovereigntyTheEuropeanoveranyterritory,totheCommissionalsodelimitationofinternationalparticipatesinthefrontiersandboundariesandworkoftheIEAtothenameofanyterritory,cityorarea.Source:IEA.InternationalEnergyAgencyWebsite:www.iea.orgInmemoryofRobertPriddle(1938-2023)ExecutiveDirectoroftheInternationalEnergyAgencyfrom1994to2002.ForewordToday,50yearsonfromtheoilshockthatledtothefoundingoftheInternationalEnergyAgency(IEA),theworldonceagainfacesamomentofhighgeopoliticaltensionsanduncertaintyfortheenergysector.Thereareparallelsbetweenthenandnow,withoilsuppliesinfocusamidacrisisintheMiddleEast–buttherearealsokeydifferences:theglobalenergysystemhaschangedconsiderablysincetheearly1970sandfurtherchangesaretakingplacerapidlybeforeoureyes.Onethingthathasn’tchangedsincethe1970sistheIEA’scommitmenttoitscoremissionofsafeguardingenergysecurity.AswehavedemonstratedthroughouttheglobalenergycrisisthateruptedinFebruary2022,theIEAisreadytorespondquicklyandeffectivelytosuddendisruptionsinenergymarkets.Atthesametime,wecontinuetodedicatesignificanteffortstoanticipatingandaddressingthechallengesthatareevolvingandemergingacrosstheentireglobalenergysystem.ThisisanareawherethedataandanalysisoftheWorldEnergyOutlook(WEO)aresovaluable.WiththeinsightsofthisnewWEOinmind,Iwanttohighlightsomeimportantdifferencesbetweenwheretheenergysectorwas50yearsagoandwhereitistoday.The1973-74crisiswasallaboutoil,buttoday’spressuresarecomingfrommultipleareas.Alongsidefragileoilmarkets,theworldhasseenanacutecrisisinnaturalgasmarketscausedbyRussia’scutstosupply,whichhadstrongknock-oneffectsonelectricity.Atthesametime,theworldisdealingwithanacuteclimatecrisis,withincreasinglyvisibleeffectsofclimatechangecausedbytheuseoffossilfuels,includingtherecord-breakingheatwavesexperiencedaroundtheworldthisyear.Acrisiswithmultipledimensionsrequiressolutionsthataresimilarlyall-encompassing.Ultimately,whatisrequiredisnotjusttodiversifyawayfromasingleenergycommoditybuttochangetheenergysystemitself,andtodosowhilemaintainingtheaffordableandsecureprovisionofenergyservices.Thegrowingimpactsofglobalwarmingmakethisallthemoreimportant,asanincreasingamountofenergyinfrastructurethatwasbuiltforacooler,calmerclimateisnolongerreliableorresilientenoughastemperaturesriseandweathereventsbecomemoreextreme.Inshort,wehavetotransformtheenergysystembothtostaveoffevenmoresevereclimatechangeandtocopewiththeclimatechangethatisalreadywithus.Aseconddifferencebetweenthe1970sandtodayisthatwealreadyhavethecleanenergytechnologiesforthejobinhand.The1973oilshockwasamajorcatalystforchange,drivingahugepushtoscaleupenergyefficiencyandnuclearpower.Butitstilltookmanyyearstorampthemupwhilesomeotherkeytechnologieslikewindandsolarwerestillemerging.Today,solar,wind,efficiencyandelectriccarsareallwellestablishedandreadilyavailable–andtheiradvantagesareonlybeingreinforcedbyturbulenceamongthetraditionaltechnologies.Wehavethelastingsolutionstotoday’senergydilemmasatourdisposal.IEA.CCB4.0.Foreword5Thethirddifferenceisthatcleanenergytransitionshaverealmomentumatthemoment.Inthe1970s,manycountriesweregoingfromastandingstartastheyscrambledtorespondtotheoilshock.AsweshowinthisWEO,cleanenergydeploymentismovingfasterthanmanypeoplerealise.Anditcanandshouldgofasterstillforustomeetoursharedenergyandclimategoals.Inaddition,wehaveinternationalprocessesandaccordsinplacetoday,suchastheParisAgreement,thatprovideanimportantframeworkforstrongeractionbygovernments.Andonefinaldifferenceis,unlikein1973,wehavetheIEA.IfirmlybelievethattheAgencyhasacrucialroletoplay–bysafeguardingagainsttraditionalenergysecurityvulnerabilities,byanticipatingnewones,and–inthewordsofourmostrecentMinisterialmandates–by“leadingtheglobalenergysector’sfightagainstclimatechange”.Theworldismuchbetterpreparedthanwewere50yearsago.Weknowwhatweneedtodoandwhereweneedtogo.Atthesametime,thechallengesaremuchbroaderandmorecomplex–energysecurityandclimateareinterwoven,andclaimingthatweneedtofocusonjustoneortheotherisablinkeredview.Wecanstilllearnfromtheresponsetotheoilshockof1973andfromtheapproachthatledtotheParisAgreementof2015:governmentsmustworktogethertoaddressourmajorcommonchallengesbecauseapatchworkofindividualeffortswillfallshort.Weneedtoco-ordinateandco-operate–thoseintheleadandwithgreaterresourcesneedtohelpthosefurtherbehindwhohaveless.Eachcountrymustfinditsownpath,butitstillneedssomesignpostsalongtheway.ThisWEOhighlights,onceagain,thechoicesthatcanmovetheenergysysteminasaferandmoresustainabledirection.Iencouragedecisionmakersaroundtheworldtotakethisreport’sfindingsintoaccount–inthelead-uptotheCOP28climatechangeconferenceinDubailaterthisyearandbeyond.IwouldliketocommendmyIEAcolleagueswhoworkedsohardonthisWEO–alongsidemanyotherkeyreports,activitiesandevents–foralltheirefforts,undertheoutstandingleadershipofLauraCozziandTimGould.WehavechosentodedicatethiseditiontoalongtimefriendoftheWEOandleadingfigureinthehistoryoftheIEA,ourformerExecutiveDirectorMrRobertPriddle,whosadlypassedawayinSeptember.AfterservingasExecutiveDirectorbetween1994and2002,MrPriddlecontinuedtomakeamajorcontributionformanyyearsaseditoroftheWEO.Inthisrole,hisdeepunderstandingofenergyandgeopoliticalmatters,aswellashisexceptionalcommunicationskills,raisedourworktoanewlevel.Wewillmisshimgreatly.DrFatihBirolExecutiveDirectorInternationalEnergyAgencyIEA.CCBY4.0.6InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023AcknowledgementsIEA.CCBY4.0.ThisstudywaspreparedbytheWorldEnergyOutlook(WEO)teamintheDirectorateofSustainability,TechnologyandOutlooks(STO)inco-operationwithotherdirectoratesandofficesoftheInternationalEnergyAgency(IEA).ThestudywasdesignedanddirectedbyLauraCozzi,Director,Sustainability,TechnologyandOutlooks,andTimGould,ChiefEnergyEconomist.ThemodellingandanalyticalteamsfortheWorldEnergyOutlook-2023wereledbyStéphanieBouckaert(demand),ChristopheMcGlade(leadonChapter4,supply),ThomasSpencer(climateandenvironment),CeciliaTam(investmentandfinance),BrentWanner(power)andDanielWetzel(sustainabletransitions).KeycontributionsfromacrosstheWEOteamwerefrom:OskarasAlšauskas(transport),CaleighAndrews(employment),YasmineArsalane(leadonChapter5,leadoneconomicoutlook,power),BlandineBarreau(governmentspending),SimonBennett(leadonhydrogen,energytechnologies),CharlèneBisch(datamanagement),EricBuisson(criticalminerals),OliviaChen(leadonbuildings,equity),YunyouChen(power),JonathanCoppel(economicoutlook),DanielCrow(leadonclimatemodelling,behaviour),JulieDallard(power,flexibility),DavideD'Ambrosio(leadondatascience,power),AmritaDasgupta(criticalminerals),TanguyDeBienassis(investmentandfinance),TomásDeOliveiraBredariol(leadonmethane,coal),NouhounDiarra(access),MichaelDrtil(power,electricitynetworks),DarlainEdeme(Africa),MusaErdogan(fossilfuelsubsidies,datamanagement),EricFabozzi(power,electricitynetworks),VíctorGarcíaTapia(buildings,datascience),EmmaGordon(Africa),AlexandraHegarty(methane),JérômeHilaire(leadonoilandgassupplymodelling),PaulHugues(leadonindustry),BrunoIdini(employment),HyejiKim(transport),Tae-YoonKim(leadoncriticalminerals,energysecurity),MartinKueppers(industry,decompositionanalysis),YannickMonschauer(leadonaffordability),AlessioPastore(power,electricitynetworks),DianaPerezSanchez(industry,affordability),ApostolosPetropoulos(leadontransport),RyszardPospiech(leadoncoalsupplymodelling,datamanagement),AlanaRawlinsBilbao(investmentandfinance),ArthurRoge(agriculture,datascience),GabrielSaive(climatepledges),MaxSchoenfisch(power,electricitysecurity),SiddharthSingh(leadonChapter5,leadonregionalanalysis),LeonieStaas(buildings,behaviour),CarloStarace(Africa),MatthieuSuire(demand-sideresponse),JunTakashiro(leadonfossilfuelsubsidies),RyotaTaniguchi(power),GianlucaTonolo(leadonenergyaccess),AnthonyVautrin(buildings,demand-sideresponse),PeterZeniewski(leadonChapter3,leadongas,energysecurity).Othercontributionswerefrom:AbdullahAl-Abri,EmileBelin-Bourgogne,Franced'Agrain,DavidFischer,PaulGrimal,MarcoIarocci,YunYoungKim,AliceLatella,CarsonMaconga,AnaMorgado,RebeccaRuffandNataliaTriunfo.MarinaDosSantos,EleniTsoukalaandRekaKoczkaprovidedessentialsupport.EdmundHoskercarriededitorialresponsibility.DebraJustuswasthecopy-editor.Acknowledgements7IEA.CCBY4.0.ColleaguesfromtheEnergyTechnologyPolicy(ETP)DivisionledbyTimurGül,ChiefEnergyTechnologyOfficer,co-ledonmodellingandanalysis,withoverallguidancefromAraceliFernandezPalesandUweRemme.PeterLevi,TiffanyVass,AlexandreGouy,LeonardoCollina,RichardSimon,FaidonPapadimouliscontributedtotheanalysisonindustry.ElizabethConnelly,JacobTeter,ShaneMcDonagh,MathildeHuismanscontributedtotheanalysisontransport.ChiaraDelmastro,RafaelMartínez-Gordóncontributedtotheanalysisonbuildings.JoséMiguelBermúdezMenéndez,StavroulaEvangelopoulou,FrancescoPavanandAmaliaPizarrocontributedtotheanalysisonhydrogen.PraveenBainscontributedtotheanalysisonbiofuels.OtherkeycontributorsfromacrosstheIEAwere:HeymiBahar,CarlosFernándezAlvarezandJeremyMoorhouse.ValuablecommentsandfeedbackwereprovidedbyotherseniormanagementandnumerousothercolleagueswithintheIEA.Inparticular,MaryWarlick,DanDorner,TorilBosoni,JoelCouse,PaoloFrankl,DennisHesseling,BrianMotherwayandHiroyasuSakaguchi.ThanksgototheIEA’sCommunicationsandDigitalOfficefortheirhelpinproducingthereportandwebsitematerials,particularlytoJethroMullen,PoeliBojorquez,CurtisBrainard,JonCuster,HortensedeRoffignac,AstridDumond,MerveErdil,GraceGordon,JuliaHorowitz,OliverJoy,IsabelleNonain-Semelin,JuliePuech,RobertStone,SamTarling,ClaraVallois,LucileWall,ThereseWalshandWonjikYang.IEA’sOfficeoftheLegalCounsel,OfficeofManagementandAdministrationandEnergyDataCentreprovidedassistancethroughoutthepreparationofthereport.ValuableinputtotheanalysiswasprovidedbyDavidWilkinson(independentconsultant).SupportforthemodellingofairpollutionandassociatedhealthimpactswasprovidedbyPeterRafaj,GregorKiesewetter,LauraWarnecke,KatrinKaltenegger,JessicaSlater,ChrisHeyes,WolfgangSchöpp,FabianWagnerandZbigniewKlimont(InternationalInstituteforAppliedSystemsAnalysis).Valuableinputtothemodellingandanalysisofgreenhousegasemissionsfromlanduse,agricultureandbioenergyproductionwasprovidedbyNicklasForsell,ZuelcladyAraujoGutierrez,AndreyLessa-Derci-Augustynczik,StefanFrank,PekkaLauri,MykolaGustiandPetrHavlík(InternationalInstituteforAppliedSystemsAnalysis).AdvicerelatedtothemodellingofglobalclimateimpactswasprovidedbyJaredLewis,ZebedeeNicholls(ClimateResource)andMalteMeinshausen(ClimateResourceandUniversityofMelbourne).Theworkcouldnothavebeenachievedwithoutthesupportandco-operationprovidedbymanygovernmentbodies,organisationsandcompaniesworldwide,notably:Enel;Eni;EuropeanCommission(DirectorateGeneralforClimateandDirectorateGeneralforEnergy);HitachiEnergy;Iberdrola;Japan(MinistryofEconomy,TradeandIndustry,andMinistryofForeignAffairs);TheResearchInstituteofInnovativeTechnologyfortheEarth,Japan;andSwissFederalOfficeofEnergy.8InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023TheIEACleanEnergyTransitionsProgramme,theIEAflagshipinitiativetotransformtheworld’senergysystemtoachieveasecureandsustainablefutureforall,supportedthisanalysis.ThanksalsogototheIEAEnergyBusinessCouncil,theIEACoalIndustryAdvisoryBoard,theIEAEnergyEfficiencyIndustryAdvisoryBoard,theIEARenewableIndustryAdvisoryBoardandtheIEAFinanceIndustryAdvisoryBoard.PeerreviewersManyseniorgovernmentofficialsandinternationalexpertsprovidedinputandreviewedpreliminarydraftsofthereport.Theircommentsandsuggestionswereofgreatvalue.Theyinclude:IEA.CCB4.0.KeigoAkimotoResearchInstituteofInnovativeTechnologyfortheEarth,JapanDougArentNationalRenewableEnergyLaboratory,UnitedStatesPapaSambaBaMinistèreduPétroleetdesEnergies,SénégalManuelBaritaudEuropeanInvestmentBankMarcoBaroniEnelFoundationHarmeetBawaHitachiEnergyChristianBessonIndependentconsultantJorgeBlazquezBPStefanBouzarovskiUniversityofManchesterMickBuffierGlencoreNickButlerKing’sCollegeLondonRebeccaCollyerEuropeanClimateFoundationRussellConklinUSDepartmentofEnergyAnne-SophieCorbeauColumbiaUniversityIanCronshawIndependentconsultantFrançoisDassaEDFJonathanElkindColumbiaUniversityJasonFarrOxfamDavidFritschUSEnergyInformationAdministrationHiroyukiFukuiToyotaMikeFulwoodNexantDavidG.HawkinsNaturalResourcesDefenseCouncilTimGoodsonIndependentconsultantFrancescaGostinelliENELYuyaHasegawaMinistryofEconomy,TradeandIndustry,JapanAcknowledgements9IEA.CCB4.0.SaraHastings-SimonUniversityofCalgaryLauryHaytayanNaturalResourceGouvernanceInstituteMasazumiHironoTokyoGasTakashiHongoMitsuiGlobalStrategicStudiesInstitute,JapanJan-HeinJesseJOSCOEnergyFinanceandStrategyConsultancySohbetKarbuzMediterraneanObservatoryforEnergyRafaelKaweckiSiemensEnergyMichaelKellyWorldLPGAssociationMsiziKhozaAbsaGroupKenKoyamaInstituteofEnergyEconomics,JapanAtsuhitoKurozumiKyotoUniversityofForeignStudies,JapanJoyceLeeGlobalWindEnergyCouncilLiJiangtaoStateGridEnergyResearchInstitute,ChinaThomas-OlivierLéautierTotalEnergiesPierre-LaurentLucilleEngieRituMathurNITIAayog,GovernmentofIndiaFelixChr.MatthesÖko-Institut–InstituteforAppliedEcology,GermanyMalteMeinshausenUniversityofMelbourne,AustraliaAntonioMerinoGarciaRepsolTatianaMitrovaSIPACenteronGlobalEnergyPolicyChristopherMoghtaderUKDepartmentforBusiness,EnergyandIndustrialStrategyIsabelMurrayDepartmentofNaturalResources,CanadaSteveNadelAmericanCouncilforanEnergy-EfficientEconomy,UnitedStatesJanPetterNoreNoradThomasNowakEuropeanHeatPumpAssociationPakYongdukKoreaEnergyEconomicsInstituteDemetriosPapathanasiouWorldBankIgnacioPérezArriagaComillasPontificalUniversity'sInstituteforResearchinTechnology,SpainAndreaPescatoriInternationalMonetaryFundGlenPetersCICEROCédricPhilibertFrenchInstituteofInternationalRelations,CentreforEnergy&ClimateVickiPollardDirectorate-GeneralforClimateAction,EuropeanCommissionAndrewPurvisWorldSteelAssociation10InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023JuliaReinaudBreakthroughEnergyOliverReynoldsGlobalOff‐GridLightingAssociationNickRobinsGranthamResearchInstituteJayRutovitzUniversityofTechnologySydneyYaminaSahebOpenEXP,IPCCauthorAnaBelénSánchezInstitutefortheJustTransition,SpainHans-WilhelmSchifferWorldEnergyCouncilJesseScottDeutschesInstitutfürWirtschaftsforschung(GermanInstituteforEconomicResearch)AdnanShihab-EldinIndependentconsultantRebekahShirleyWorldResourcesInstituteMariaSiciliaEnagásPaulSimonsYaleUniversityGurdeepSinghNationalThermalPowerCorporationLimitedJimSkeaImperialCollegeLondon,IPCCCo-ChairWorkingGroupIIIJonathanSternOxfordInstituteforEnergyStudies,UnitedKingdomMiguelGilTertreDirectorateGeneralforEnergy,EuropeanCommissionWimThomasIndependentconsultantRahulTongiaCentreforSocialandEconomicProgess,IndiaNikosTsafosGeneralSecretariatofthePrimeMinisteroftheHellenicRepublicAdairTurnerEnergyTransitionsCommissionJamesTurnureUSEnergyInformationAdministrationFridtjofFossumUnanderAkerHorizonsNoéVanHulstInternationalPartnershipforHydrogenandFuelCellsintheEconomyDavidVictorUniversityofCalifornia,SanDiego,UnitedStatesAndrewWalkerCheniereEnergyCharlesWeymullerEDFKelvinWongDBSBankChristianZinglersenEuropeanUnionAgencyfortheCooperationofEnergyRegulatorsIEA.CCB4.0.Acknowledgements11TheworkreflectstheviewsoftheInternationalEnergyAgencySecretariat,butdoesnotnecessarilyreflectthoseofindividualIEAmembercountriesorofanyparticularfunder,supporterorcollaborator.NoneoftheIEAoranyfunder,supporterorcollaboratorthatcontributedtothisworkmakesanyrepresentationorwarranty,expressorimplied,inrespectofthework’scontents(includingitscompletenessoraccuracy)andshallnotberesponsibleforanyuseof,orrelianceon,thework.Thisdocumentandanymapincludedhereinarewithoutprejudicetothestatusoforsovereigntyoveranyterritory,tothedelimitationofinternationalfrontiersandboundariesandtothenameofanyterritory,cityorarea.Commentsandquestionsarewelcomeandshouldbeaddressedto:LauraCozziandTimGouldDirectorateofSustainability,TechnologyandOutlooksInternationalEnergyAgency9,ruedelaFédération75739ParisCedex15FranceE-mail:weo@iea.orgMoreinformationabouttheWorldEnergyOutlookisavailableatwww.iea.org/weo.IEA.CCB4.0.12InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023TableofContentsForeword.................................................................................................................................5Acknowledgements.................................................................................................................7Executivesummary...............................................................................................................171Overviewandkeyfindings23Introduction...........................................................................................................251.1Apeakby2030foreachofthefossilfuels....................................................261.1.1Coal:Scalingupcleanpowerhastensthedecline.............................271.1.2Oil:Endofthe“ICEage”turnsprospectsaround..............................281.1.3Naturalgas:Energycrisismarkstheendofthe“GoldenAge”..........291.2AslowdownineconomicgrowthinChinawouldhavehugeimplicationsforenergymarkets........................................................................................311.2.1China’sgrowthhasdefinedtheenergyworldinrecentdecades.....311.2.2IntegratingaslowdowninChina’seconomyintotheSTEPS.............321.2.3SensitivitiesintheOutlook................................................................351.3Aboomofsolarmanufacturingcouldbeaboonfortheworld....................361.3.1Solarmodulemanufacturingandtrade.............................................371.3.2SolarPVdeploymentcouldscaleupfastertoacceleratetransitions381.4Pathwaytoa1.5°Climitonglobalwarmingisverytough,butitremainsopen.................................................................................................421.4.1Fourreasonsforhope.......................................................................421.4.2Fourareasrequiringurgentattention...............................................461.5Capitalflowsaregainingpace,butnotreachingtheareasofgreatestneed491.5.1Fossilfuels.........................................................................................501.5.2Cleanenergy......................................................................................511.6Transitionshavetobeaffordable..................................................................521.6.1Affordabilityforhouseholds..............................................................531.6.2Affordabilityforindustry...................................................................551.6.3Affordabilityforgovernments...........................................................571.7Risksontheroadtoamoreelectrifiedfuture..............................................591.7.1Managingrisksforrapidelectrification.............................................601.7.2Criticalmineralsunderpinelectrification..........................................62IEA.CCB4.0.1.8Anew,lowercarbonpathwayforemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesistakingshape.............................................................................63TableofContents131.9Geopoliticaltensionsundermineenergysecurityandprospectsforrapid,affordabletransitions....................................................................................681.9.1Cleanenergyinalow-trustworld.....................................................691.9.2Fossilfuelsinalow-trustworld.........................................................711.9.3Risksofnewdividinglines.................................................................721.10Asthefactschange,sodoourprojections....................................................731.10.1SolarPVandwindgeneration...........................................................751.10.2Naturalgas.........................................................................................772Settingthescene792.1NewcontextfortheWorldEnergyOutlook..................................................812.1.1Newcleanenergyeconomy..............................................................842.1.2Uneasybalanceforoil,naturalgasandcoalmarkets.......................862.1.3Keychallengesforsecureandjustcleanenergytransitions.............882.2WEOscenarios...............................................................................................912.2.1Policies...............................................................................................922.2.2Economicanddemographicassumptions.........................................932.2.3Energy,criticalmineralandcarbonprices.........................................952.2.4Technologycosts...............................................................................993Pathwaysfortheenergymix1013.1Introduction.................................................................................................1033.2Overview.....................................................................................................1043.3Totalfinalenergyconsumption...................................................................1073.3.1Industry............................................................................................1083.3.2Transport.........................................................................................1133.3.3Buildings..........................................................................................1183.4Electricity.....................................................................................................1233.5Fuels............................................................................................................1303.5.1Oil....................................................................................................1303.5.2Naturalgas.......................................................................................1353.5.3Coal..................................................................................................1403.5.4Modernbioenergy...........................................................................145IEA.CCB4.0.3.6Keycleanenergytechnologytrends...........................................................14714InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20234Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions1554.1Introduction.................................................................................................1574.2Environmentandclimate............................................................................1584.2.1Emissionstrajectoryandtemperatureoutcomes...........................1584.2.2Methaneabatement........................................................................1614.2.3Airquality........................................................................................1644.3Secureenergytransitions............................................................................1664.3.1Fuelsecurityandtrade....................................................................1664.3.2Electricitysecurity...........................................................................1714.3.3Cleanenergysupplychainsandcriticalminerals............................1784.4People-centredtransitions..........................................................................1834.4.1Energyaccess...................................................................................1834.4.2Energyaffordability.........................................................................1874.4.3Energyemployment........................................................................1914.4.4Behaviouralchange.........................................................................1934.5Investmentandfinanceneeds....................................................................1975Regionalinsights2035.1Introduction.................................................................................................2055.2UnitedStates...............................................................................................2065.2.1Keyenergyandemissionstrends....................................................2065.2.2HowmuchhavetheUSInflationReductionActandotherrecentpolicieschangedthepictureforcleanenergytransitions?.............2085.3LatinAmericaandtheCaribbean................................................................2115.3.1Keyenergyandemissionstrends....................................................2115.3.2WhatroleforLatinAmericaandtheCaribbeaninmaintainingtraditionaloilandgassecuritythroughenergytransitions?...........2135.3.3DocriticalmineralsopennewavenuesforLatinAmericaandtheCaribbean’snaturalresources?.......................................................2145.4EuropeanUnion...........................................................................................2165.4.1Keyenergyandemissionstrends....................................................2165.4.2CantheEuropeanUniondeliveronitscleanenergyandcriticalmaterialstargets?............................................................................2185.4.3WhatnextforthenaturalgasbalanceintheEuropeanUnion?.....219IEA.CCB4.0.5.5Africa...........................................................................................................221TableofContents155.5.1Keyenergyandemissionstrends....................................................2215.5.2Rechargingprogresstowardsuniversalenergyaccess....................2235.5.3WhatcanbedonetoenhanceenergyinvestmentinAfrica?..........2245.6MiddleEast..................................................................................................2265.6.1Keyenergyandemissionstrends....................................................2265.6.2Shiftingfortunesforenergyexports................................................2285.6.3Howisthedesalinationsectorchangingintimesofincreasingwaterneedsandtheenergytransition?.........................................2295.7Eurasia.........................................................................................................2315.7.1Keyenergyandemissionstrends....................................................2315.7.2What’snextforoilandgasexportsfromEurasia?..........................2335.8China............................................................................................................2365.8.1Keyenergyandemissionstrends....................................................2365.8.2HowsoonwillcoalusepeakinChina?............................................2385.9India.............................................................................................................2415.9.1Keyenergyandemissionstrends....................................................2415.9.2ImpactofairconditionersonelectricitydemandinIndia...............2435.9.3WilldomesticsolarPVmodulemanufacturingkeeppacewithsolarcapacitygrowthinIndia?........................................................2445.10JapanandKorea..........................................................................................2465.10.1Keyenergyandemissionstrends....................................................2465.10.2Challengesandopportunitiesofnuclearandoffshorewind...........2485.10.3Whatrolecanhydrogenplayintheenergymixandhowcanthegovernmentsdeployit?...................................................................2495.11SoutheastAsia.............................................................................................2515.11.1Keyenergyandemissionstrends....................................................2515.11.2HowcaninternationalfinanceacceleratecleanenergytransitionsinSoutheastAsia?...........................................................................2535.11.3Howcanregionalintegrationhelpintegratemorerenewables?....254AnnexesIEA.CCB4.0.AnnexA.Tablesforscenarioprojections............................................................................259AnnexB.Designofthescenarios........................................................................................295AnnexC.Definitions............................................................................................................319AnnexD.References...........................................................................................................339AnnexE.InputstotheGlobalEnergyandClimateModel..................................................34716InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023ExecutiveSummaryTheenergyworldremainsfragilebuthaseffectivewaystoimproveenergysecurityandtackleemissionsSomeoftheimmediatepressuresfromtheglobalenergycrisishaveeased,butenergymarkets,geopolitics,andtheglobaleconomyareunsettledandtheriskoffurtherdisruptioniseverpresent.Fossilfuelpricesaredownfromtheir2022peaks,butmarketsaretenseandvolatile.ContinuedfightinginUkraine,morethanayearafterRussia’sinvasion,isnowaccompaniedbytheriskofprotractedconflictintheMiddleEast.Themacro-economicmoodisdownbeat,withstubborninflation,higherborrowingcostsandelevateddebtlevels.Today,theglobalaveragesurfacetemperatureisalreadyaround1.2°Cabovepre-industriallevels,promptingheatwavesandotherextremeweatherevents,andgreenhousegasemissionshavenotyetpeaked.Theenergysectorisalsotheprimarycauseofthepollutedairthatmorethan90%oftheworld’spopulationisforcedtobreathe,linkedtomorethan6millionprematuredeathsayear.Positivetrendsonimprovingaccesstoelectricityandcleancookinghaveslowedorevenreversedinsomecountries.Againstthiscomplexbackdrop,theemergenceofanewcleanenergyeconomy,ledbysolarPVandelectricvehicles(EVs),provideshopeforthewayforward.Investmentincleanenergyhasrisenby40%since2020.Thepushtobringdownemissionsisakeyreason,butnottheonlyone.Theeconomiccaseformaturecleanenergytechnologiesisstrong.Energysecurityisalsoanimportantfactor,particularlyinfuel-importingcountries,asareindustrialstrategiesandthedesiretocreatecleanenergyjobs.Notallcleantechnologiesarethrivingandsomesupplychains,notablyforwind,areunderpressure,buttherearestrikingexamplesofanacceleratingpaceofchange.In2020,onein25carssoldwaselectric;in2023,thisisnowonein5.Morethan500gigawatts(GW)ofrenewablesgenerationcapacityaresettobeaddedin2023–anewrecord.MorethanUSD1billionadayisbeingspentonsolardeployment.Manufacturingcapacityforkeycomponentsofacleanenergysystem,includingsolarPVmodulesandEVbatteries,isexpandingfast.ThismomentumiswhytheIEArecentlyconcluded,initsupdatedNetZeroRoadmap,thatapathwaytolimitingglobalwarmingto1.5°Cisverydifficult–butremainsopen.ThisnewOutlookprovidesastrongevidencebasetoguidethechoicesthatfaceenergydecisionmakersinpursuitoftransitionsthatarerapid,secure,affordableandinclusive.Theanalysisdoesnotpresentasingleviewofthefuturebutinsteadexploresdifferentscenariosthatreflectcurrentreal-worldconditionsandstartingpoints.TheStatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS)providesanoutlookbasedonthelatestpolicysettings,includingenergy,climateandrelatedindustrialpolicies.TheAnnouncedPledgesScenario(APS)assumesallnationalenergyandclimatetargetsmadebygovernmentsaremetinfullandontime.Yet,muchadditionalprogressisstillrequiredtomeettheobjectivesoftheNetZeroEmissionsby2050(NZE)Scenariowhichlimitsglobalwarmingto1.5°C.Alongsideourmainscenarios,weexploresomekeyuncertaintiesthatcouldaffectfuturetrends,includingstructuralchangesinChina’seconomyandthepaceofglobaldeploymentofsolarPV.IEA.CCB4.0.ExecutiveSummary17Weareontracktoseeallfossilfuelspeakbefore2030Alegacyoftheglobalenergycrisismaybetousherinthebeginningoftheendofthefossilfuelera:themomentumbehindcleanenergytransitionsisnowsufficientforglobaldemandforcoal,oilandnaturalgastoallreachahighpointbefore2030intheSTEPS.Theshareofcoal,oilandnaturalgasinglobalenergysupply–stuckfordecadesaround80%–startstoedgedownwardsandreaches73%intheSTEPSby2030.Thisisanimportantshift.However,ifdemandforthesefossilfuelsremainsatahighlevel,ashasbeenthecaseforcoalinrecentyears,andasisthecaseintheSTEPSprojectionsforoilandgas,itisfarfromenoughtoreachglobalclimategoals.Policiessupportingcleanenergyaredeliveringastheprojectedpaceofchangepicksupinkeymarketsaroundtheworld.ThankslargelytotheInflationReductionActintheUnitedStates,wenowprojectthat50%ofnewUScarregistrationswillbeelectricin2030intheSTEPS.Twoyearsago,thecorrespondingfigureintheWEO-2021was12%.IntheEuropeanUnionin2030,heatpumpinstallationsintheSTEPSreachtwo-thirdsofthelevelneededintheNZEScenario,comparedwiththeone-thirdprojectedtwoyearsago.InChina,projectedadditionsofsolarPVandoffshorewindto2030arenowthree-timeshigherthantheywereintheWEO-2021.Prospectsfornuclearpowerhavealsoimprovedinleadingmarkets,withsupportforlifetimeextensionsofexistingnuclearreactorsincountriesincludingJapan,KoreaandtheUnitedStates,aswellasfornewbuildsinseveralmore.Althoughdemandforfossilfuelshasbeenstronginrecentyears,therearesignsofachangeindirection.Alongsidethedeploymentoflow-emissionsalternatives,therateatwhichnewassetsthatusefossilfuelsarebeingaddedtotheenergysystemhasslowed.Salesofcarsandtwo/three-wheelvehicleswithinternalcombustionenginesarewellbelowwheretheywerebeforetheCovid-19pandemic.Intheelectricitysector,worldwideadditionsofcoal-andnaturalgas-firedpowerplantshavehalved,atleast,fromearlierpeaks.SalesofresidentialgasboilershavebeentrendingdownwardsandarenowoutnumberedbysalesofheatpumpsinmanycountriesinEuropeandintheUnitedStates.Chinahaschangedtheenergyworld,butnowChinaischangingChinahasanoutsizedroleinshapingglobalenergytrends;thisinfluenceisevolvingasitseconomyslowsanditsstructureadjusts,andascleanenergyusegrows.Overthepasttenyears,Chinaaccountedforalmosttwo-thirdsoftheriseinglobaloiluse,nearlyone-thirdoftheincreaseinnaturalgas,andhasbeenthedominantplayerincoalmarkets.Butitiswidelyrecognised,includingbythecountry’sleadership,thatChina’seconomyisreachinganinflectionpoint.Afteraveryrapidbuildingoutofthecountry’sphysicalinfrastructure,thescopeforfurtheradditionsisnarrowing.Thecountryalreadyhasaworld-classhigh-speedrailnetwork;andresidentialfloorspacepercapitaisnowequaltothatofJapan,eventhoughGDPpercapitaismuchlower.Thissaturationpointstolowerfuturedemandinmanyenergy-intensivesectorslikecementandsteel.Chinaisalsoacleanenergypowerhouse,accountingforaroundhalfofwindandsolaradditionsandwelloverhalfofglobalEVsalesin2022.IEA.CCB4.0.18InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCB4.0.MomentumbehindChina’seconomicgrowthisebbingandthereisgreaterdownsidepotentialforfossilfueldemandifitslowsfurther.Inourscenarios,China’sGDPgrowthaveragesjustunder4%peryearto2030.Thisresultsinitstotalenergydemandpeakingaroundthemiddleofthisdecade,withrobustexpansionofcleanenergyputtingoverallfossilfueldemandandemissionsintodecline.IfChina’snear-termgrowthweretoslowbyanotherpercentagepoint,thiswouldreduce2030coaldemandbyanamountalmostequaltothevolumecurrentlyconsumedbythewholeofEurope.Oilimportvolumeswoulddeclineby5%andLNGimportsbymorethan20%,withmajorimplicationsforglobalbalances.NewdynamicsforinvestmentaretakingshapeTheendofthegrowtheraforfossilfuelsdoesnotmeananendtofossilfuelinvestment,butitundercutstherationaleforanyincreaseinspending.Untilthisyear,meetingprojecteddemandintheSTEPSimpliedanincreaseinoilandgasinvestmentoverthecourseofthisdecade,butastrongercleanenergyoutlookandlowerprojectedfossilfueldemandmeansthisisnolongerthecase.However,investmentinoilandgastodayisalmostdoublethelevelrequiredintheNZEScenarioin2030,signallingaclearriskofprotractedfossilfuelusethatwouldputthe1.5°Cgoaloutofreach.SimplycuttingspendingonoilandgaswillnotgettheworldontrackfortheNZEScenario;thekeytoanorderlytransitionistoscaleupinvestmentinallaspectsofacleanenergysystem.Thedevelopmentofacleanenergysystemanditseffectonemissionscanbereinforcedbypoliciesthateasetheexitofinefficient,pollutingassets,suchasageingcoalplants,orthatrestricttheentryofnewonesintothesystem.Buttheurgentchallengeistoincreasethepaceofnewcleanenergyprojects,especiallyinmanyemerginganddevelopingeconomiesoutsideChina,whereinvestmentinenergytransitionsneedstorisebymorethanfivetimesby2030toreachthelevelsrequiredintheNZEScenario.Arenewedeffort,includingstrongerinternationalsupport,willbevitaltotackleobstaclessuchashighcostsofcapital,limitedfiscalspaceforgovernmentsupportandchallengingbusinessenvironments.MeetingdevelopmentneedsinasustainablewayiskeytomovingfasterTheglobalpeaksindemandforeachofthethreefossilfuelsmaskimportantdifferencesacrosseconomiesatdifferentstagesofdevelopment.Thedriversforgrowthindemandforenergyservicesinmostemerginganddevelopingeconomiesremainverystrong.Ratesofurbanisation,builtspacepercapita,andownershipofairconditionersandvehiclesarefarlowerthaninadvancedeconomies.Theglobalpopulationisexpectedtogrowbyabout1.7billionby2050,almostallofwhichisaddedtourbanareasinAsiaandAfrica.Indiaistheworld’slargestsourceofenergydemandgrowthintheSTEPS,aheadofSoutheastAsiaandAfrica.Findingandfinancinglow-emissionswaystomeetrisingenergydemandintheseeconomiesisavitaldeterminantofthespeedatwhichglobalfossilfueluseeventuallyfalls.Cleanelectrification,improvementsinefficiencyandaswitchtolower-andzero-carbonfuelsarekeyleversavailabletoemerginganddevelopingeconomiestoreachtheirnationalenergyandclimatetargets.Gettingontracktomeetthesetargets,includingnetzerogoals,hasbroadimplicationsforfuturepathways.InIndia,itmeanseverydollarofvalueaddedbyExecutiveSummary19IEA.CCB4.0.India’sindustryresultsin30%lesscarbondioxide(CO2)by2030thanitdoestoday,andeachkilometredrivenbyapassengercar,onaverage,emits25%lessCO2.Some60%oftwo-andthree-wheelerssoldin2030areelectric,asharetentimeshigherthantoday.InIndonesia,theshareofrenewablesinpowergenerationdoublesby2030tomorethan35%.InBrazil,biofuelsmeet40%ofroadtransportfueldemandbytheendofthedecade,upfrom25%today.Insub-SaharanAfrica,meetingdiversenationalenergyandclimatetargetsmeansthat85%ofnewpowergenerationplantsto2030arebasedonrenewables.Significantprogressismadetowardsuniversalaccesstomodernenergy,withsome670millionpeoplegainingaccesstomoderncookingfuels,and500milliontoelectricityby2030.AmpleglobalmanufacturingcapacityoffersconsiderableupsideforsolarPVRenewablesaresettocontribute80%ofnewpowercapacityto2030intheSTEPS,withsolarPValoneaccountingformorethanhalf.However,thisusesonlyafractionoftheworld’spotential.SolarhasbecomeamajorglobalindustryandissettotransformelectricitymarketsevenintheSTEPS.Butthereissignificantscopeforfurthergrowthgivenmanufacturingplansandthetechnology’scompetitiveness.Bytheendofthedecade,theworldcouldhavemanufacturingcapacityformorethan1200GWofpanelsperyear.ButintheSTEPS,only500GWisdeployedgloballyin2030.Boostingdeploymentupfromtheselevelsraisessomecomplexquestions.Itwouldrequiremeasures–notablyexpandingandstrengtheninggridsandaddingstorage–tointegratetheadditionalsolarPVintoelectricitysystemsandmaximiseitsimpact.Manufacturingcapacityisalsohighlyconcentrated:Chinaisalreadythelargestproduceranditsexpansionplansfaroutstripthoseinothercountries.Trade,therefore,wouldcontinuetobevitaltosupportworldwidedeploymentofsolar.Using70%ofanticipatedsolarPVmanufacturingcapacitywouldbringdeploymenttothelevelsprojectedintheNZEScenario;effectivelyintegrated,thiswouldfurthercutfossilfueluse–firstandforemostcoal.Inasensitivitycase,weexplorehowtheSTEPSprojectionswouldchangeiftheworldaddedover800GWofnewsolarPVperyearby2030.TheimplicationswouldbeparticularlystrongforChina,reducingcoal-firedgenerationbyafurther20%by2030comparedwiththeSTEPS.Withoutassuminganyadditionalretirements,theaverageannualcapacityfactorforcoal-firedpowerplantswouldfalltoaround30%in2030,fromover50%today.TheconsequenceswouldspreadwellbeyondChina:inthiscase,morethan70GWofadditionalsolarPVisdeployedonaverageeachyearto2030acrossLatinAmerica,Africa,SoutheastAsiaandtheMiddleEast.Evenwithmodestcurtailment,thisreducesfossilfuel-firedgenerationintheseregionsbyaboutone-quarterin2030comparedwiththeSTEPS.SolarPValonecannotgettheworldontracktomeetitsclimategoals,but–morethananyothercleantechnology–itcanlightuptheway.AwaveofnewLNGexportprojectsissettoremodelgasmarketsStartingin2025,anunprecedentedsurgeinnewLNGprojectsissettotipthebalanceofmarketsandconcernsaboutnaturalgassupply.Inrecentyears,gasmarketshavebeendominatedbyfearsaboutsecurityandpricespikesafterRussiacutsuppliestoEurope.Marketbalancesremainprecariousintheimmediatefuturebutthatchangesfromthemiddleofthedecade.Projectsthathavestartedconstructionortakenfinalinvestment20InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCB4.0.decisionaresettoadd250billioncubicmetresperyearofliquefactioncapacityby2030,equaltoalmosthalfoftoday’sglobalLNGsupply.Announcedtimelinessuggestaparticularlylargeincreasebetween2025and2027.MorethanhalfofthenewprojectsareintheUnitedStatesandQatar.ThisadditionalLNGarrivesatanuncertainmomentfornaturalgasdemandandcreatesmajordifficultiesforRussia’sdiversificationstrategytowardsAsia.ThestrongincreaseinLNGproductioncapacityeasespricesandgassupplyconcerns,butcomestomarketatatimewhenglobalgasdemandgrowthhasslowedconsiderablysinceits“goldenage”ofthe2010s.Alongsidegascontractedonalonger-termbasistoend-users,weestimatethatmorethanone-thirdofthenewgaswillbelookingtofindbuyersontheshort-termmarket.However,maturemarkets–notablyinEurope–aremovingintostrongerstructuraldeclineandemergingmarketsmaylacktheinfrastructuretoabsorbmuchlargervolumesifgasdemandinChinaslows.TheglutofLNGmeansthereareverylimitedopportunitiesforRussiatosecureadditionalmarkets.Russia’sshareofinternationallytradedgas,whichstoodat30%in2021,ishalvedby2030intheSTEPS.AffordabilityandresiliencearewatchwordsforthefutureAtensesituationintheMiddleEastisareminderofhazardsinoilmarketsayearafterRussiacutgassuppliestoEurope.Vigilanceonoilandgassecurityremainsessentialthroughoutcleanenergytransitions,andourprojectionshighlighthowthebalanceoftradeandpotentialvulnerabilitiesshiftovertime.IntheSTEPS,theshareofseabornecrudeoiltradefromtheMiddleEasttoAsiarisesfromsome40%ofthetotaltodayto50%by2050.AsiaisalsothefinaldestinationforalmostallofadditionalMiddleEastLNGsupply.Theglobalenergycrisiswasnotacleanenergycrisis,butithasfocusedattentionontheimportanceofensuringrapid,people-centredandorderlytransitions.Threeinterlinkedissuesstandout:riskstoaffordability,electricitysecurityandtheresilienceofcleanenergysupplychains.Shelteringconsumersfromvolatilefuelpricesin2022costgovernmentsUSD900billioninemergencysupport.Thewaytolimitsuchexpendituresinthefutureistodeploycost-effective,cleantechnologiesatscale,especiallyinpoorerhouseholds,communitiesandcountriesthatstruggletofinancetheupfrontinvestmentsrequired.Astheworldmovestowardsamoreelectrified,renewables-basedsystem,securityofelectricitysupplyisalsoparamount.Higherinvestmentinrobustanddigitalisedgridsneedstobeaccompaniedbyaroleforbatteriesanddemandresponsemeasuresforshort-termflexibilityandlower-emissionstechnologiesforseasonalvariations,includinghydropower,nuclear,fossilfuelswithcarboncapture,utilisationandstorage,bioenergy,hydrogenandammonia.Diversificationandinnovationarethebeststrategiestomanagesupplychaindependenciesforcleanenergytechnologiesandcriticalminerals.Arangeofstrategiesareinplacetostrengthentheresilienceofcleanenergysupplychainsandreducetoday’shighlevelsofconcentration,butthesewilltaketimetobearfruit.Explorationandproductioninvestmentsarerisingaroundtheworldforcriticalmineralslikelithium,cobalt,nickelandrareearths,buttheshareofthetopthreeproducersin2022iseitherunchangedorhasincreasedfrom2019levels.OurtrackingofannouncedprojectssuggestsconcentrationlevelsExecutiveSummary21IEA.CCB4.0.in2030aresettoremainhigh,especiallyforrefiningandprocessingoperations.Manymidstreamprojectsarebeingdevelopedintoday’smajorproducingregions,withChinaholdinghalfofplannedlithiumchemicalplantsandIndonesiarepresentingnearly90%ofplannednickelrefiningfacilities.Alongsideinvestmentsindiversifiedsupply,policiesencouraginginnovation,mineralsubstitutionandrecyclingcanmoderatetrendsonthedemandsideandeasemarketpressures.Theyarevitalcomponentsofcriticalmineralssecurity.Weneedtogomuchfurtherandfaster,butafragmentedworldwillnotrisetomeetourclimateandenergysecuritychallengesProvenpoliciesandtechnologiesareavailabletoalignenergysecurityandsustainabilitygoals,speedupthepaceofchangethisdecadeandkeepthedoorto1.5°Copen.TheSTEPSseesapeakinenergy-relatedCO2emissionsinthemid-2020sbutemissionsremainhighenoughtopushupglobalaveragetemperaturestoaround2.4°Cin2100.ThisoutcomehasimprovedoversuccessiveeditionsoftheOutlookbutstillpointstowardsverywidespreadandsevereimpactsfromclimatechange.Thekeyactionsrequiredtobendtheemissionscurvedownwardsto2030arewidelyknownandinmostcasesverycosteffective.Triplingrenewableenergycapacity,doublingthepaceofenergyefficiencyimprovementsto4%peryear,rampingupelectrificationandslashingmethaneemissionsfromfossilfueloperationstogetherprovidemorethan80%oftheemissionsreductionsneededby2030toputtheenergysectoronapathwaytolimitwarmingto1.5°C.Inaddition,innovative,large-scalefinancingmechanismsarerequiredtosupportcleanenergyinvestmentsinemerginganddevelopingeconomies,asaremeasurestoensureanorderlydeclineintheuseoffossilfuels,includinganendtonewapprovalsofunabatedcoal-firedpowerplants.Everycountryneedstofinditsownpathway,anditneedstobeinclusiveandequitabletosecurepublicacceptance,butthispackageofglobalmeasuresprovidescrucialingredientsforanysuccessfuloutcomefromtheCOP28climatechangeconferenceinDubaiinDecember.Nocountryisanenergyisland,andnocountryisinsulatedfromtherisksofclimatechange.Thenecessityofcollaborationhasneverbeenhigher.Especiallyintoday’stensetimes,governmentsneedtofindwaystosafeguardco-operationonenergyandclimate,includingbyembracingarules-basedsystemofinternationaltradeandspurringinnovationandtechnologytransfer.Withoutthis,thechancetolimittheriseinglobaltemperaturesto1.5°Cwilldisappear.Theoutlookforenergysecuritywillalsolookperilousifwelosethebenefitsofinterconnectedandwell-functioningenergymarketstorideoutunexpectedshocks.Fiftyyearsonfromthefirstoilshock,theworldhaslastingsolutionstoaddressenergyinsecuritythatcanalsohelptackletheclimatecrisis.Thefirstoilshock50yearsagobroughttwocrucialpolicyresponsesfirmlyintoplay:energyefficiencyandlow-emissionspower,ledatthetimebyhydropowerandnuclear.Today’senergydecisionmakersareonceagainfacinggeopoliticaltensionsandtheriskofenergyshocks,buttheyhaveamuchbroaderrangeofhighlycompetitivecleantechnologiesattheirdisposal,andanaccumulatedwealthofpolicyexperienceonhowtoacceleratetheirdeployment.Thecrucialstepistoputthesereadilyavailablesolutionstowork.22InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Chapter1OverviewandkeyfindingsTransitionsaregettingcompetitiveSUMMARY•ConflictanduncertaintyprovideaninauspiciousbackdroptothenewWorldEnergyOutlook.FollowingRussia’sinvasionofUkraine,instabilityintheMiddleEastcouldleadtofurtherdisruptiontoenergymarketsandprices.Thisunderscoresonceagainthefrailtiesofthefossilfuelage,andthebenefitsforenergysecurityaswellasforemissionsofshiftingtoamoresustainableenergysystem.•Cleanenergyprojectsarefacingheadwindsinsomemarketsfromcostinflation,supplychainbottlenecksandhigherborrowingcosts.Butcleanenergyisthemostdynamicaspectofglobalenergyinvestment.Howfastitgrowsinthecomingdecadesinresponsetopolicyandmarketstimuliiskeytoexplainthedifferencesintrajectoriesandoutcomesacrossourthreemainscenarios.Inallscenarios,themomentumbehindthecleanenergyeconomyisenoughtoproduceapeakindemandforcoal,oilandnaturalgasthisdecade,althoughtheratesofpost-peakdeclinevarywidely.•IntheStatedPoliciesScenario,averageannualgrowthrateof0.7%intotalenergydemandto2030isaroundhalftherateofenergydemandgrowthofthelastdecade.Demandcontinuestoincreasethroughto2050.IntheAnnouncedPledgesScenario,totalenergydemandflattens,thankstoimprovedefficiencyandtheinherentefficiencyadvantagesoftechnologiespoweredbyelectricity–suchaselectricvehiclesandheatpumps–overfossilfuel-basedalternatives.IntheNetZeroEmissionsby2050Scenario,electrificationandefficiencygainsproceedevenfaster,leadingtoadeclineinprimaryenergyof1.2%peryearto2030.•Ouranalysisexploressomekeyuncertainties,notablyregardingthepaceofChina’seconomicgrowthandthepossibilitiesformorerapidsolarPVdeploymentopenedbyamassiveplannedexpansioninmanufacturingcapacity(ledbyChina).Wehighlighttheimplicationsofahugeincreaseinthecapacitytoexportliquefiednaturalgasstartinginthemiddleofthisdecade,ledbytheUnitedStatesandQatar.Weexaminehowanydeteriorationingeopoliticaltensionswouldundermineboththeprospectsforenergysecurityandforrapid,affordabletransitions.•Extremevolatilityinenergymarketsduringtheglobalenergycrisishashighlightedtheimportanceofaffordable,reliableandresilientsupply,especiallyinprice-sensitivedevelopingeconomiesthatseethelargestincreaseindemandforenergyservices.Energytransitionsrelyonelectrificationandtechnologieslikewind,solarPVandbatteries,andpushelectricitysecurityanddiversifiedsupplyforcleantechnologiesandcriticalmineralsupthepolicyagenda.Emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesaccountforalmost80%oftheglobalgrowthinelectricitydemandintheStatedPoliciesScenario,andforovertwo-thirdsintheotherscenarios.IEA.CCB4.0.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings23SolarPVislighting2030STEPS2030apathforwardfor500GW12.3Gtcleanenergytransitions2022STEPS+120+140+65-1.6Gt220GWadditionsintheNZESolarCase201550GW120GWAdditionalintheNZESolarCasePowersectorCO2emissionsChinaManufacturingAdvancedeconomiescapacityOtheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies640GW1260GWSolarmanufacturinggrowthisoutpacingtheriseofAround250bcmofnewsolarPVdeployment,creatingsomerisksofliquefactioncapacityissettocomeimbalancesbuthugeopportunitiesfortheworldtoonlineby2030,ofwhichtheUnitedaccelerateenergytransitions.StatesandQataraccountfor60%.AwaveofnewLNGexportprojectsissettooverturngasmarketsCapacityadditionsAfricaUnitedStatesQatarOther2015Australia20112030SoutheastAsia2022CanadaRussia400bcm635bcmTotalcapacity885bcm350bcmAsChina’sdemandgrowthEJ4slows,cleanenergypushesUnabatedfossilfuelsfossilfuelsintodeclineAnnualchangeinenergyconsumptionCleanenergy2200020232050-2IntroductionSomeofthetensionsinenergymarketsrecededin2023sincetheextremevolatilityofthe1globalenergycrisis,butthesituationremainsfragile.Theurgenttaskoftransformingtheenergysystemnowtakesplaceinamorechallengingmacroeconomicandgeopoliticalcontext.Thefrailtiesofthefossilfuelageandthehazardsthatithascreatedfortheplanetareplaintosee,andopportunitiesintheemergingcleanenergyeconomyaregrowingfast.Butmanyuncertaintiesremainabouttheresilienceofenergysupplychainsoldandnew,aboutriskstothesecurityandaffordabilityoftransitions,andaboutwhethertheprocessofchangewillbesufficientlyrapidtoavoidverysevereimpactsfromachangingclimate.Usingthelatestdataforenergymarkets,policiesandtechnologies,theWorldEnergyOutlook(WEO)providesinsightsonallthesekeyissues.Itdoessobyexploringscenariosthatreflectdifferentassumptionsabouttheactionstakeninthecomingyearstoshapeenergysystemsandreduceenergy-relatedcarbondioxide(CO2)emissions.TheprojectionsintheStatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS)giveasenseofthecurrentdirectionoftravelfortheenergyeconomy,basedontheactualstateofplayindifferentsectors,countriesandregions.TheAnnouncedPledgesScenario(APS)showshowthatfuturewouldbedifferentifallcountriesweretohittheiraspirationaltargets,includingnationalandregionalnetzeroemissionspledges,ontimeandinfull.TheupdatedNetZeroEmissionsby2050(NZE)Scenarioillustrateswhatmoreisrequiredtolimitglobalwarmingto1.5degreeCelsius(°C).Thisoverviewchapterprovidestentakeawaysfromthenewanalysis.OurprojectionsshowthatforthefirsttimedemandforeachofthefossilfuelsreachapeakintheSTEPSbeforetheendofthisdecade.WeexaminehowuncertaintiesoverthepaceofeconomicgrowthinThePeople’sRepublicofChina(hereinafterChina)couldaffectthenear-termoutlook,aswellastheimplicationsoftheextraordinaryChina-ledboominmanufacturingcapacityforsolarphotovoltaic(PV)modules.Wehighlightareasofhopeandareasforcautionabouttheprospectsofstayingwithinthe1.5°Climit,andexaminethecrucialissueofcapitalflowsforcleanenergyandfossilfuels.Againstabackgroundofmacroeconomicuncertainty,weconsidertheaffordabilityofthetransitionforhouseholds,industryandgovernments.Astheworldcomestorelymoreandmoreonelectricity,welookatrisksaffectingtechnologiesthathaveakeyparttoplayinincreasingelectrificationanddecarbonisingthepowersupply.Wealsoaskwhetherthepolicyandtechnologychoicesfacingemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesopenthepossibilityofanewlowercarbonpathwayfordevelopment.Inaddition,weidentifythewaysinwhichgeopoliticaltensionscouldaffecttheOutlook,andlookbacktoseehowandwhyourprojectionshavechangedovertime.IEA.CCBY4.0.ThetopicsincludedinthischapterrepresentkeythemesoftheWorldEnergyOutlook2023.FurtherinformationandbackgroundontheIEANetZeroRoadmapisinNetZeroRoadmap:AGlobalPathwaytoKeepthe1.5°CGoalinReachpublishedinSeptember2023.Inaddition,arangeofsupplyanddemandissuesfortheoilandgasindustryandtheirrelationtotheOutlookarethefocusofaforthcomingspecialreportinNovember2023.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings251.1Apeakby2030foreachofthefossilfuelsIntheWEO-2023,theStatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS)seeslowerdemandprojectionsforeachofthefossilfuelsthanintheWEO-2022.Thisreflectscurrentpolicysettingsbygovernmentsworldwide,aslightdownwardrevisionintheeconomicoutlook,andthecontinuedramificationsofthe2022globalenergycrisis.Italsoreflectslongertermtrends:fossilfueltechnologieshavebeenlosingmarketsharetocleanenergytechnologiesacrossvarioussectorsinrecentyears,andinmanycasesfossilfuel-poweredtechnologieshavealreadyseenapeakinsalesoradditions.Theseshiftsmeanthateachofthethreefossilfuelcategoriesarenowprojectedtoreachapeakby2030(Figure1.1).ThishasneverpreviouslybeenseenintheSTEPS.Thechangesinourprojectionshighlighthowtheenergysystemischangingaslow-emissionselectricityandfuelsmeetanincreasingshareoftheworld’srisingenergyneeds,andasenergyefficiencyimprovementshelptomoderatethoseneeds.Totaldemandforfossilfuelsdeclinesfromthemid-2020sbyanaverageof3exajoules(EJ)peryearto2050intheSTEPS,andthepeakinenergy-relatedCO2emissionsintheSTEPSisbroughtforwardtothemid-2020s.Figure1.1⊳FossilfuelconsumptionbyfuelintheSTEPS,2000-2050Index(peakvalue=100%)100%Naturalgas90%OilCoal80%70%60%50%201020202030204020502000IEA.CCBY4.0.Allfossilfuelspeakbeforetheendofthisdecade,withdeclinesinadvancedeconomiesandChinaoffsettingincreasingdemandelsewhereIEA.CCBY4.0.Wehighlightbelowsomeofthekeydriversforthesechangesbyfuel,buttherearesomeimportantissuestobearinmindwhenconsideringthesetrends.First,theprojecteddeclinesindemandafterthepeaksarenowherenearsteepenoughtobeconsistentwiththeNZEScenario–gettingontrackforthisscenariowillrequiremuchfastercleanenergydeploymentandmuchmoredeterminedpolicyactionbygovernments(section1.4).Second,thedemandtrendsforthedifferentfuelsvaryconsiderablyamongregions,withreduced26InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023demandinadvancedeconomiespartiallyoffsetbycontinuedgrowthinmanyemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,particularlyfornaturalgas.Third,whilethetrajectoriesiinnopurarcstciceen.aTrihoesrreefwleilcltiunnevdietarlbyliyngbsetrsupciktuersa,ldcihpasnagneds,ptlhaetedaeumsaanlodnogutthloeowkawyi.llFnoortebxeamlinpelaer,1heatwavesanddroughtscouldwellcausetemporaryjumpsincoaldemandbypushingupelectricityuseatatimewhenhydropoweroutputmaybeconstrained.Evenasdemandforfossilfuelsfalls,energysecuritychallengeswillremainsincetheprocessofadjustmenttochangingdemandpatternswillnotnecessarilybeeasyorsmooth.Forexample,thepeaksindemandweseebasedontoday’spoliciesdonotremovetheneedforinvestmentinoilandgassupply,givenhowsteepthenaturaldeclinesfromexistingfieldsoftenare.Atthesametime,theyunderlinetheeconomicandfinancialrisksofmajornewoilandgasprojects,ontopoftheirrisksforclimatechange(section1.5).1.1.1Coal:ScalingupcleanpowerhastensthedeclineAfterremainingconsistentlyhighoverthepastdecade,globalcoaldemandisnowsettofallwithinthenextfewyearsintheSTEPS(Figure1.2).Thisprojectedtrendreflectsdeclinesinrecentyearsofcapacityadditionsofbothcoal-firedpowerandcoal-firedironandsteelproduction–thetwolargestconsumersofcoaltoday–whichaccountfor65%and16%respectivelyofoverallcoalconsumption.Figure1.2⊳GlobalcoaldemandbysectorandannualaveragechangebyregionintheSTEPS,2000-2050Mtce6000CoaldemandMtceAnnualaveragechange5000SteelCement7550Power400025300002000-251000-5020002010202020302040-752010-2022-2030-2050202220302050AEChinaOtherEMDEPowerSteelCementOtherPeakyearincoalcapacityadditionsIEA.CCBY4.0.Peaksincoalcapacityadditionsreachedinthepower,steelandcementsectorsarelayingthefoundationforglobalcoaldemandtopeakinthemid-2020sIEA.CCBY4.0.Note:Mtce=milliontonnesofcoalequivalent;AE=advancedeconomies;EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings27Theshareofcoal-firedpowerinnewworldwidecapacityadditionshitahighpointin2006at45%andhassincefallensteadilyto11%in2022.Thesizeofannualcoalcapacityadditionspeakedin2012atover100gigawatts(GW)beforedroppingto50GWin2022,withbiginvestmentsincoalfallingawayrapidly,andsolarPVandwindpowerincreasinglydominatingtheexpansionofelectricitysystems.Theroleofcoal-firedpowerplantshasstartedtoshifttowardsprovidingflexibilityandsystemservicesratherthanbulkpower.Asaresult,theaveragecapacityfactorofcoalpowerplantswasalmosttenpercentagepointsloweroverthepastdecadethanduringthedecadebefore.Changesinironandsteelproductionhavealsocontributedtothedeclineincoaldemand.Capacityadditionsofcoal-basedsteelproductionplants1peakedin2003atover130milliontonnes(Mt),driveninlargepartbyChina’srapidindustrialisation.Elevenyearslater,globalcoaldemandforironandsteelproductionpeakedatover950milliontonnesofcoalequivalent(Mtce)beforestartingtofall,despiteacontinuingsteadyincreaseintheproductionofironandsteel.Thedeclineintheglobalcoalintensityofsteelproductionsince2015istheresultofgrowthintheshareofscrap-basedproductioninelectricarcfurnaces,aswellasalternativestoblastfurnacesforironproductionsuchasnaturalgas-baseddirectreducediron.Inadvancedeconomies,coaldemandpeakedin2007.InChina–theworld’slargestcoalconsumer–theimpressivegrowthofrenewablesandnuclearalongsidemacroeconomicshiftspointtoadecreaseincoalusebythemid-2020s.Coalusecontinuestoincreaseinotheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesasnewpowerplantsandindustrycapacitycomeonline,butthisgrowthismorethanoffsetbyprojecteddeclineselsewhere.1.1.2Oil:Endofthe“ICEage”turnsprospectsaroundInthepasttwodecades,oildemandhassurgedby18millionbarrelsperday(mb/d).Muchoftheincreasehasbeendrivenbyrisingdemandinroadtransport.Theglobalcarfleetexpandedbymorethan600millioncarsoverthelast20years,androadfreightactivityhasincreasedbyalmost65%.Roadtransportnowaccountsforaround45%ofglobaloildemand,whichisfarmorethananyothersector:thepetrochemicalssector,second-largestinoilconsumption,accountsfor15%ofoildemand.Theastoundingriseinelectricvehicle(EV)salesisnowhavinganimpactondemandforoilinroadtransport.Salesofgasolineanddieselcars,two/three-wheelersandtruckspeakedin2017,2018and2019respectively(Figure1.3).In2020,EVsaccountedfor4%ofglobalcarsales.Theyareontracktoreach18%in2023with14millionEVsales,mostlyinChinaandtheadvancedeconomies,andaresettocontinuetoincreaserapidlyinthefuture.Salesofinternalcombustionengine(ICE)busesalsopeakbythemid-2020sintheSTEPS,withtheuptakeofelectricbusesrisingparticularlyquicklyinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Bytheendofthisdecade,roadtransportisnolongerasourceofoildemandgrowth.IEA.CCBY4.0.1Includesblastfurnaces-basicoxygenfurnaces,smeltingreduction-basicoxygenfurnace,coal-baseddirectreducediron-electricarcfurnace,coal-basedironininductionorinopenhearthfurnaces.28InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Figure1.3⊳GlobaloildemandbysectorandannualaveragechangebyregionintheSTEPS,2000-2050Oildemand1Annualaveragechange1200.75mb/d0.50mb/dCarsTwo/three-wheelersTrucks100800.2560040-0.2520-0.5020002010202020302040-0.752010-2022-2030-2050202220302050PassengervehiclesTrucksPeakinICEvehiclesalesNon-roadtransportOtherAEChinaOtherEMDEIEA.CCBY4.0.Salesofgasolineanddieselpassengervehiclesandtruckshavealreadypeaked,leadingtoapeakinoildemandbefore2030Note:mb/d=millionbarrelsperday;AE=advancedeconomies;EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Althoughoildemandforpetrochemicals,aviationandshippingcontinuestoincreasethroughto2050intheSTEPS,thisisnotenoughtooffsetreductionsindemandfromroadtransport,aswellasinthepowerandbuildingssectors.Asaresult,oildemandpeaksbefore2030.ThedeclinefromthepeakhoweverisaslowoneintheSTEPSallthewaythroughto2050.Theoutlookforoildemandvariesacrossregions.Oildemandinadvancedeconomiespeakedin2005,anditsdeclinebecomesmorepronouncedinthecomingdecade.China’srobustoildemandgrowthsince2010weakensinthecomingyearsanddeclinesinthelongrun.Inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies(otherthanChina),whichseegrowingpopulationsandcarownership,oildemandgrowscontinuouslyto2050.1.1.3Naturalgas:Energycrisismarkstheendofthe“GoldenAge”The“GoldenAgeofGas”,atermcoinedbytheIEAin2011,isnearinganend.Globalnaturalgasusehasincreasedbyanannualaverageofalmost2%since2011,butgrowthslowsintheSTEPStolessthan0.4%peryearfromnowuntil2030.Thepowerandbuildingssectors–today’sbiggestconsumersofnaturalgasaccountingfor39%and21%respectivelyoftotaldemand–havealreadyseenpeaksinnaturalgascapacityadditionsforpowerplantsandspaceheatingboilers,andmuteddemandinthesetwosectorsreducesnaturalgasuseenoughtocauseittopeakby2030(Figure1.4).IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings29Figure1.4⊳GlobalnaturalgasdemandbysectorandannualaveragechangebyregionintheSTEPS,2000-20506000NaturalgasdemandAnnualaveragechange5000Boilersinbuildings30bcm4000bcm20Power10300002000-101000-2020002010202020302040-302010-2022-2030-2050202220302050PowerBuildingsIndustryOtherAEChinaOtherEMDEPeakyearingascapacityadditionsIEA.CCBY4.0.Additionsofnewgaspowerplantsandgasboilersinbuildingsareslowing;gasdemandpeaksbefore2030intheSTEPS,thoughgasuseinindustrycontinuestoincreaseNote:bcm=billioncubicmetres;AE=advancedeconomies;EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.IEA.CCBY4.0.Thehighpointfornaturalgaspowercapacityadditionswasin2002,whentheyexceeded100GWandmadeuparound65%oftotalannualcapacityadditions.Capacityadditionsfelltolessthan30GWin2022.Despitethisslowinginannualadditions,theglobalinstalledcapacityofnaturalgaspowercontinuestoexpandovertime.Gasdiffersinthisrespectfromcoal,whereinstalledcapacityreducesinthefuture.NaturalgasdemandinthepowersectorneverthelessdeclinesintheSTEPSfromtodayuntil2050,withaparticularlystrongdipinthe2030swhenco-firingingas-firedpowerplantsbeginstobedeployedatscale.Salesofgas-firedboilersforspaceheatinginbuildingshavealsopeaked.Attheirheight,gasboilersaccountedforaround40%oftotalsalesofspaceheatingequipment.Thesubsequentdeclineinsalesoverthelastfewyearsreflectstherapidriseofheatpumps,especiallyinadvancedeconomies.HeatpumpsaleshaveastrongimpactongasdemandinthebuildingssectorintheSTEPStrajectorybecausespaceheatingisbyfartheleadingend-useintermsofnaturalgasdemandtoday.Inadvancedeconomies,thereboundinnaturalgasdemandseenin2021didnotlastlong,anddemandin2022wasbelowpre-pandemiclevels.Thisfalteringindemandreflectsashifttorenewablesinelectricitygeneration,theriseofheatpumps,andEurope’sacceleratedmoveawayfromgasfollowingtheRussianFederation(hereinafterRussia)invasionofUkraine.DemandcontinuestodeclineintheSTEPS,andby2030thismorethanoffsetscontinueddemandgrowthinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.30InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20231.2AslowdownineconomicgrowthinChinawouldhavehugeimplicationsforenergymarkets1.2.1China’sgrowthhasdefinedtheenergyworldinrecentdecades1China’seconomicgrowthhasbeenanepoch-makingeventoverthelastseveraldecades.Since1995,Chinaaccountedfortwo-thirdsofthedeclineintheglobalpopulationlivinginextremepoverty.ItsGDPpercapitaincreasedmorethanseven-timesinthesameperiod,asitseconomytransformedintoagloballyintegrated,innovativeindustrialpowerhouse.Figure1.5⊳China’sshareinthechangeofselectedglobaleconomicandenergysectorindicators,2012-2022100%80%60%40%20%GDPEnergyEnergy-RenewablesdemandrelatedCO₂capacityIEA.CCBY4.0.China’sgrowthhastransformedtheglobaleconomy,energysectorandenvironmentNote:GDPismeasuredatmarketexchangerates.Morerecently,overthecourseofthelastdecadeChinawasresponsibleformorethanone-thirdofgrowthinglobalGDP(Figure1.5).China’sgrowthhasdonemuchtoshapeenergymarketsandtheglobalenvironment:inthelastdecade,itaccountedformorethan50%ofglobalenergydemandgrowthand85%oftheriseinenergysectorCO2emissions.Butitseconomyischanging.China’sleadershavelongacknowledgedthatitscurrentphaseofmassiveandresource-intensiveinvestmentinurbanisation,infrastructureandfactoriesmustend.Asfarbackas2007,China’sthenPremierwarnedthat"thebiggestproblemwithChina'seconomyisthatgrowthisunstable,unbalanced,uncoordinatedandunsustainable".ThisrebalancingcouldhavesubstantialimpactsontheoutlookforChina’senergysector,andgivenChina’ssize,fortheworldtoo.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings311.2.2IntegratingaslowdowninChina’seconomyintotheSTEPSTherebalancingoftheChineseeconomystillhasalongwaytogo.Savingsandinvestmentlevelsremainveryhigh,thedebt-to-GDPratiohascontinuedtoclimb,andtheconstructionsectorretainsanoutsizedroleinGDP(Figure1.6).Thismodelispushingagainstinherentconstraints.Chinaalreadyhasaworld-classinfrastructurestock,andaftergrowingalmost30%inthelastdecadeitspercapitaresidentialfloorspaceisalreadyequaltothatofJapan,despiteChina’slowerlevelofGDPpercapita.China’sworkingagepopulationpeakedaround2015andisprojectedtofallbymorethan20%by2050.Withthiswillcomeareducedneedforinvestment,suchasinnewhousingandinfrastructure(Figure1.7).Figure1.6⊳SelectedindicatorsofstructuralchangeintheChineseeconomy,2010-2022InvestmentDebtConstructionandalliedsectors(shareofGDP)(shareofGDP)(shareofindustrialVA)50%350%50%40%280%40%30%210%30%20%140%20%10%70%10%201020222010202220102022IEA.CCBY4.0.RebalancingofChina’seconomystillhasalongwaytogowithinvestment,debt-to-GDPratio,andshareoftheconstructionsectorinGDPremaininghighNotes:GDPisexpressedinmarketexchangerateterms.VA=valueadded.Alliedsectorsarebasicchemicalsandfertilisers,basicmetals,non-metallicminerals,pulpandpaper,woodandwoodproductsexcludingfurniture.Debtreferstototaloutstandingcredittothenon-financialsectorfromalllendingsectors,expressedasapercentofGDP.Sources:IEAanalysisbasedondatafromOxfordEconomics(2023)andBIS(2023).IEA.CCBY4.0.AlthoughthecurrentpropertycrisisinChinahasattractedmuchattention,ithasnotyetsignificantlyimpactedtheenergysector(Box1.1).Moreover,thepropertycrisisisasymptomofthebroadstructuralchangefacingtheChineseeconomy.HowthiseconomictransitionplaysoutisoneofthekeyuncertaintiesinthisOutlook.Inourscenarios,wehavereviseddownwardsthelong-termprojectionofGDPgrowthinChinatojustunder4%peryearfortheperiod2022to2030,and2.3%peryearfortheperiod2031to2050.Thiscomparestomorethan4.5%andmorethan2.5%respectivelyintheWorldEnergyOutlook-2022scenarios.Asaresult,theeconomyisaround5%smallerin2030thanprojectedlast32InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023year,andslightlylessthan15%smallerin2050.Despitethesechanges,Chinaremainsacriticaldriverofglobalgrowth,accountingforalmostone-thirdofglobalGDPgrowthto2030itnheoumrisdcdelneaorifost.hBisudteslcoawdee;rgwriothwtshtarbelseulatsndintChheinnas’lsotwoltyaldeencelirnginygdedmemanadndp,eaclkeianngaernoeurngdy1growthissufficienttodriveadeclineinfossilfueldemandandhenceemissions.Figure1.7⊳SelectedeconomicindicatorsandannualtotalenergydemandgrowthinChinaintheSTEPS,2010–2050Economicindicators(peak=1)Energydemandgrowth(EJ)1.0Workingage12Unabatedpopulationfossil0.98fuels0.8Cementproduction4Cleanenergy0.7Steelproduction00.6202020302040-42020203020402050201020502010IEA.CCBY4.0.Cement,steelandworkingagepopulationeachhavepeakedandaresettodecline;asChina’seconomychanges,energydemandgrowthwillslow,peakanddeclineSource:PopulationprojectionfromtheMedianVariantoftheWorldPopulationProspects(UNDESA,2022).Box1.1⊳Thepropertycrisisiseverywhere,exceptintheenergystatisticsDespitetheimportanceoftheunfoldingpropertycrisis,China’senergydemandanditsheavyindustrialproductionappearonlymodestlyaffected.Thetotalfloorspaceofnewprojectsstartedperyearfellaround50%from2019to2022;butfloorspaceunderconstruction,despitefallingin2022,isstill1%higherthanin2019(Figure1.8).Inotherwords,thepropertycrisishasimpactednewprojects,notthosealreadyunderconstruction.Thisexplainswhymaterialandenergydemandhasbeenlessimpactedthanindicatorslikenewprojectstartsorpropertydevelopershareorbondprices.ItalsoimpliesthatifChina’spropertysectorsettlesintoalowerlevelofactivity,overtimethiswillimpactthestockofprojectsunderconstructionandhenceenergyandmaterialdemandunderlyingconstructionprojects.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings33Figure1.8⊳Selectedpropertysectorindicators,China,2011-2022PropertyindicatorsPropertyindicatorsUnderconstruction120%CompletedUnderconstruction12Index(2019=100%)Billionm²100%1080%860%Newfloorspace6SalesSalesstarted440%Newfloorspacestarted20%2201120222011Completed2022IEA.CCBY4.0.Sofar,thepropertycrisishashittheflowofnewprojectstarts,buthashadlimitedimpactonthestockofprojectsunderconstructionSource:IEAanalysisbasedondatafromtheNationalBureauofStatisticsofChina(NBSC,2023).IEA.CCBY4.0.Thereareseveraladditionalreasons,bothstructuralandcyclical,whichexplainwhyenergydemandhasbeenresilientinthefaceofthedownturninthepropertysectorinChina:Rapidelectrificationhasdrivenstrongelectricitydemandgrowth.Electricitygenerationaccountedformorethan70%oftheincreaseinenergydemandsince2015inChina.“Neweconomy”sectorshavebeengrowingstrongly,includinghigh-techmanufacturingincleanenergyareassuchasPVandEVs.Whiletheaverageannualgrowthoffixedassetinvestmentinpropertyhasshrunkbyaround5%sinceJanuary2022,ithasgrownbyabout15%forautomobilemanufacturing,forexample.Totakeanotherexample,revenueinthelastyearforlistedsolarPVmanufacturersandautomobilemanufacturersamountedtoUSD166billionandUSD135billionrespectively.Chinaismassivelyincreasingitsdomesticpetrochemicalproduction.Between2019and2024,ChinaissettoaddasmuchpetrochemicalcapacityasthecombinedcapacityofallOECDcountriesinEuropeandAsia.Feedstockdemandforpetrochemicalproductionhasincreased50%since2019andisresponsibleforaround80%ofgrowthinoilproductdemandinChinaoverthe2019to2023period.Droughtsin2021and2022constrainedhydroelectricityproduction(andarecontinuingtodosoin2023).Withoutthisfactor,China’stotalenergydemandgrowthwouldhavebeenlessin2022,anditsCO2emissionswouldhavedeclinedratherthanrisenmarginally.34InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20231.2.3SensitivitiesintheOutlookButoutcomesotherthanthoseintheSTEPSarepossible.Toexplorepossibleimplications,wehavemodelledaLowCaseandaHighCase.IntheLowCase,China’sGDPisaround7.5%1lowerin2030thanintheSTEPS,withamorerapiddeclineininfrastructureandpropertyinvestmentnotfullyoffsetbyanincreaseinconsumptionandinvestmentinothersectors.Cementproductionisaround14%lowerthanintheSTEPS,forexample.TheLowCaseassumesslowerbutultimately“higherquality”growth.2TheHighCaseassumesthereverse,withadelayedrebalancingtemporarilyincreasingGDPgrowthwhileatthesametimenegativelyimpactinglongertermeconomicsustainability.Figure1.9⊳KeyenergyindicatorsforChinaintheLowCaseversustheSTEPS,2030CoalOilNaturalgasTotalCO₂(Mtce)(mb/d)(bcm)(Mt)-50-0.2-6-200-100-0.4-12-400-150-0.6-18-600-200-0.8-24-800-250-1.0-30-1000IEA.CCBY4.0.SlowerbuthighqualitygrowthinthisdecadewouldhavelargeimpactsonworldenergymarketsandChina’sCO2emissionsIntheLowCase,primarycoaldemandisaround7%lowerthanintheSTEPSin2030duetolowerlevelsofproductioninheavyindustries,lesselectricitydemand,andcontinuedrobustexpansionoflow-emissionssourcesofelectricitygeneration(Figure1.9).Oilislessaffectedthancoal,withprimarydemandaround0.75mb/dlowerthanintheSTEPS,butthedeclineindemandneverthelessrepresentstheequivalentofabout5%inprojected2030oilimportsintheSTEPS(orabout2%oftheglobalmarket).Naturalgasisalsolessaffectedthancoal,withdemandalmost30billioncubicmetres(bcm)lowerin2030thanintheSTEPS,thoughstillover15%higherthanin2022.ThisreductionrepresentstheequivalentofmorethanIEA.CCBY4.0.2Increasinglyusedinofficialdiscourse,thephrase“highquality”growthistakentomeaneconomicgrowthbasedondomesticconsumption,externaldemandandbusinessinvestmentinproductivesectors,asopposedtocontinuedgrowthbasedonhighinvestmentinpropertyandinfrastructurewithlowanddiminishingproductivityreturns.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings3520%ofChina’sprojectedliquefiednaturalgas(LNG)importsintheSTEPSin2030.ThesevariouschangesresultinCO2emissionsthataremorethan0.8gigatonnes(Gt)lowerin2030thanintheSTEPS,andnearly15%lowerthanin2022.Ontheotherhand,theHighCaseseesstrongercoaldemandandhigherCO2emissions.Emissionsstillpeakbefore2030,butin2030areabout0.8GthigherthanintheSTEPS,and1.6GthigherthanintheLowCase.AsintheLowCase,theimpactacrossfuelsisnotsymmetrical,withlessofanupsideforoilthanforcoal.InboththeHighCaseandtheLowCase,theweightofChinainglobalenergymarketsmeansthatthechangeshavesignificantglobalimplications.ThisdiscussionhighlightstheimportanceofpayingcloseattentiontoChina’smacroeconomicevolution.TheLowCase,predicatedonlowerbuthigherqualitygrowth,wouldhavesubstantialandprobablydeflationaryimpactsonglobalenergycommodityandtechnologymarkets.Atthesametime,increasedemphasisonexport-orientedsectors,includingcleanenergytechnologysectors,inordertopartiallyoffsetthedeclineofotherssuchaspropertycouldhaveimplicationsfor–alreadystrained–traderelations.Ontheotherhand,aprolongationofthecurrentinfrastructureandpropertyintensivemodelmightprovideanear-termboosttoenergyandcommoditymarkets,butitwouldalsoincreaseCO2emissionsandcouldstoreeconomicproblemsforthefuture.1.3AboomofsolarmanufacturingcouldbeaboonfortheworldSolarmanufacturinghasexperiencedaremarkableexpansionoverthelastdecade,increasingten-foldgloballytomeetincreasingdemandforcleanenergy.Thistrendissettocontinueatanelevatedpace,withinvestmentsinthepipelinesettoraiseglobalsolarmodulemanufacturingcapacityfromabout640GWin2022toover1200GWinthemediumterm(Figure1.10).Pairedwithrapidexpansionalongthesupplychain–fromtheproductionofpolysilicontowafersandsolarcells–solarPVispoisedtoacceleratecleanenergytransitionsaroundtheworld.SolarPVhasbeenoneofthemajorsuccessesofthepastdecade,withannualdeploymentofelectricitygenerationcapacitygrowingmorethansevenfold.Manufacturingcapacityexpansionhasbeenevenfasterandthegaphasdrivendowntheutilisationrateofsolarmanufacturingfromcloseto60%tobelow40%in2022.Thisiswellbelowthe70%levelthatwouldnormallybeconsideredhealthyforamatureindustry.IntheSTEPS,globalsolarPVdeploymentcontinuestoexpandfromaround220GWin2022toabout500GWin2030,butplannedmanufacturingexpansionmeansthattheutilisationrateofsolarmanufacturingremainsbelow40%throughto2030.ThescopetomakefulleruseofsolarmanufacturingcapacityrepresentsanenormousopportunitytoacceleratethedeploymentofsolarPVaroundtheworldandaccelerateenergytransitions.IEA.CCBY4.0.36InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Figure1.10⊳GlobalsolarmodulemanufacturingandsolarPVcapacityadditionsintheSTEPS,2010-2030GW1200160%Productioncapacity100050%Historical800Planned40%Utilisationrate(rightaxis)60030%STEPSsolarPV40020%capacityadditions20010%2010201520222030IEA.CCBY4.0.PlannedexpansionofsolarmanufacturingoutpacessolarPVcapacityadditionsto2030;itslowutilisationratepresentsahugeopportunitytoacceleratecleanenergytransitions1.3.1SolarmodulemanufacturingandtradeSolarmanufacturingtodayishighlyconcentrated–justfivecountriesaccountforover90%ofglobalcapacity.Chinaisfarandawaythelargest,withthecapacitytoproducesolarmoduleswithanoutputofover500GWeveryyear,equivalentto80%ofworldmanufacturingcapacity.TheotherfourareVietNam(5%oftheglobalmarket),India(3%),Malaysia(3%)andThailand(2%).Thenextfiveleadingsolarmanufacturers–theUnitedStates,Korea,Cambodia,TürkiyeandChineseTaipei–eachaccountforaround1%oftheglobaltotal,asdoestheEuropeanUnion.Whilefewerthan40countrieshavecapacitytoproducesolarmodules,over100countriescompletedsolarPVprojectsin2022,whichmostlyreliedonimportedsolarpanels.Chinaistheprimaryexporterofsolarpanels(IEA,2022a).Itsexports,andthoseofotherexporters,facilitatetheexpansionofrenewableenergyinmarketsaroundtheworld.SoutheastAsiaisthesecond-largestexporter,withmanyofthepanelsitexportsgoingtotheUnitedStatesandtheEuropeanUnion.AsdomesticmanufacturingcapacityinIndiahasincreasedinrecentyears,thereispotentialtoreduceimportdependenceoverthecomingyears.Today,theEuropeanUnionandtheUnitedStatesarethelargestimportersofsolarpanels.NewimporttariffshaverecentlybeenputinplaceintheUnitedStatesonsolarmodulesthatoriginateinChina:thesearesettochangethepatternofimportstotheUnitedStates,andmayhaveknock-oneffectsinothermarkets.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings37Figure1.11⊳PlannedsolarmodulemanufacturingcapacityandsolarPVcapacityadditionsintheSTEPS,2030SolarmoduleexportersSolarmoduleimporters801200GWGW900606004030020ChinaSoutheastIndiaUnitedEuropeanRestofAsiaStatesUnionworldPlannedsolarmodulemanufacturing2030solarPVcapacityadditionsIEA.CCBY4.0.Solarmanufacturingissettoexpandinmorethanadozencountries:Chinaremainsthelargestexporter,whiletheEuropeanUnionandUnitedStatesremainthemainimportersPlansforadditionalcapacitysuggestthatsolarmanufacturingwillremainhighlyconcentrated,andthattradewillcontinuetobeimportantformanymarkets(Figure1.11).Chinaplanstoaddanother500GWofsolarmodulemanufacturingcapacityinthecomingyears,faroutstrippingplansfornewcapacityinothercountries.Expansiononthisscalemeansthatitislikelytomaintainits80%shareoftheglobaltotalandtoremaintheprimaryexporterofsolarmodulesbysomedistance.Indiaaimstocontinueexpandingitsproductioncapacitytomeetdomesticneedsandtoexportsolarmodules:projectsinthepipelineundertheProductionLinkedIncentivesschemesuggestthatitsmanufacturingcapacitycouldexceed70GWperyearby2027.ProductioncapacityinSoutheastAsiaissettooutpaceregionalneeds,allowingittoremainanimportantexporter.IntheUnitedStates,plannedsolarmoduleproductioncapacityinvestmentshavebeenboostedbytheInflationReductionAct,andareoncoursetoincreasesixfoldinthemediumterm.However,withoutfurtherinvestment,significantimportswillstillbeneededtomeetfastgrowingsolarPVdeploymentintheSTEPSin2030.SolarmanufacturingintheEuropeanUnionissettodoubleinthemediumterm,butheretoodeploymentisincreasingrapidly,andabout70%ofdeploymentin2030willdependonimportedsolarmodulesunlessfurtherinvestmentsaremadeinmanufacturingintheEuropeanUnion.IEA.CCBY4.0.1.3.2SolarPVdeploymentcouldscaleupfastertoacceleratetransitionsPlannedincreasesinsolarPVmanufacturingcapacityaroundtheworldhavethepotentialtoenableover800GWofnewsolarPVtobedeployedin2030,whichisinlinewiththelevelofdeploymentreachedintheNZEScenarioin2030(Figure1.12).Thiswouldraisetheaverage38InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023utilisationrateforsolarmodulemanufacturingtoaround70%,whichisroughlywhatmightbeexpectedinamatureindustry.WehaveconstructedtheNZESolarCasewhichlooksatwouhtactomweosuilnd2h0a3p0pweinthifthaolsletihnisthpeoStTeEnPtiSa.lThsoelarerstcaopfathciitsysewctaisontahpigpheldighatnsdthcisocmopmapraersistohne.1Figure1.12⊳GlobalsolarPVandbatterystoragecapacityadditionsandpowersectorCO2emissions,2022and2030SolarPVandbatterycapacityadditionsPowersectorCO₂emissions100015GWGtCO₂800126009400620032022STEPSNZEsolar2022STEPSNZEsolarSolarPV20302030BatterystorageIEA.CCBY4.0.TakingadvantageofsolarmanufacturingcapacitycouldliftsolarPVdeploymenttoover800GWby2030,inlinewiththeNZEScenario,cuttingpowersectoremissions30%by2030Note:GW=gigawatts;Gt=gigatonnes;NZEsolar=NZESolarCase.IEA.CCBY4.0.AnimportantinitialpointisthatrapidfurtherdeploymentofsolarPVintheNZESolarCasewouldrequiremeasurestointegratetheadditionalsolarPVintoelectricitysystemsandmaximiseitsimpact.ScalingupbatterystoragewouldbecrucialinmostcasestoimprovethealignmentofsolarPVoutputwithelectricitydemandpatternsandsystemneeds.IntheNZESolarCase,utility-scalebatterydeploymentin2030isclosetodoublethelevelintheSTEPS.Measurestomoderniseandexpandnetworks,facilitatedemandresponseandboostpowersystemflexibilitywouldalsobenecessary.AcceleratingsolarPVdeploymenttothelevelsintheNZEScenariowouldreduceCO2emissionsin2030bydisplacingsomeunabatedfossilfuels.GlobalCO2emissionsfromthepowersectorwouldfallbelow11Gtin2030,some15%lowerthanthelevelintheSTEPSin2030and30%belowthelevelin2022.Coal-firedelectricitygenerationwouldbearound15%lowerthanintheSTEPSin2030:thedeclineincoal-firedgenerationwouldlargelytakeplaceinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesandwoulddeliverthebulkoftheemissionsreductions.Naturalgas-firedelectricitygenerationwouldalsobereducedby15%comparedwiththeSTEPSin2030,withreductionsinbothadvancedeconomiesandemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings39ChinacouldacceleratesolarPVdeploymenttoshiftawayfromcoalfasterIntheSTEPS,solarPVcapacityadditionsinChinareachover270GWperyearbeforeflattening.Whilethismeansamarkedslowingoftherateofgrowthachievedinrecentyears,itstillputsChinafiveyearsaheadofscheduletoreach1200GWofsolarPVandwindcapacity,whichisoneofthetargetsfor2030initsNationallyDeterminedContribution.Nevertheless,thereisscopeforChinatoaccelerateitsuptakeofbothdistributedsolarPVandlarge-scaleprojects.IntheNZESolarCase,China’sannualsolarPVcapacityadditionsexceed400GWby2030(Figure1.13).TosuccessfullyintegratetheadditionalsolarPVandkeepcurtailmentatmanageablelevels,batterystorageandnetworkenhancementswouldbeasimportantinChinaaseverywhereelse.Continuedprogressonpowersystemreforms,includingfurthermovestowardsaunifiednationalpowermarket,wouldhelpmakethebestuseoftheadditionalsolarPV(IEA,2023a).Figure1.13⊳SolarPVcapacityadditionsandcoal-firedelectricitygenerationinChinaintheSTEPSandNZESolarCase,2020-2035SolarPVcapacityadditions6000Coal-firedelectricitygeneration600GWTWhNZEsolarcase4004000STEPS200200020202025203020352020202520302035IEA.CCBY4.0.Withtargetedintegrationmeasures,ChinacoulddeploysignificantlymoresolarPVandputcoal-firedpowerintoasteeperdeclineIEA.CCBY4.0.Effectivelyintegrated,highersolarPVdeploymentwouldacceleratethetransitionawayfromcoal-firedpowerinChina.Whilecoal-firedgenerationwouldstillpeakaround2025,itwoulddeclinemoresteeplyafterwards.By2030,thelevelofcoal-firedgenerationintheNZESolarCasewouldbe20%lowerthanintheSTEPSand35%lowerthanin2022.Withoutassuminganyadditionalretirements,theaverageannualcapacityfactorforcoal-firedpowerplantswouldfalltoabout30%in2030,comparedwithabout40%intheSTEPSandover50%in2022.Asaresult,powersectorCO2emissionswouldfalltoabout4.2Gtin2030,a30%reductionfromthe2022level.40InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023EmergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiescouldalsoshiftawayfromcoalfasterSparesolarPVmanufacturingcapacitycouldalsofacilitatefasteruptakeoflowcostsolarPVinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChina.IntheNZESolarCase,more1than70GWofadditionalsolarPVisdeployedeachyearto2030acrossAfrica,LatinAmericaandtheCaribbean(LAC),MiddleEastandSoutheastAsia.Evenwithmodestamountsofcurtailment,thiswouldreducebothnaturalgas-firedandcoal-firedpowergenerationbyaboutone-quarterin2030comparedwiththelevelsintheSTEPS,cuttingpowersectorCO2emissionsin2030byover500Mt,30%ofthetotal.TheMiddleEastwouldalsohavetheopportunitytocutbothcoalandnaturalgasuseinpower,whileinLACtheadditionalsolarPVwouldmostlyreducedemandfornaturalgas-firedgeneration;inAfricaandSoutheastAsia,itsbiggestimpactwouldbeoncoal-firedpower(Figure1.14).Figure1.14⊳AdditionalsolarPVcapacityadditionsintheNZESolarCaseandrelatedimpactsinselectedregionsrelativetotheSTEPS,2030GW3060%AdditionalsolarPV20capacityperyear40%to203010Impacts(rightaxis):20%Coal-firedgeneration00%Naturalgas-firedgeneration-10-20%PowersectorCO₂emissions-20-40%-30Africa-60%SoutheastAsiaMiddleEastEMDEinLACIEA.CCBY4.0.AdditionalsolarPVdeployedinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiescouldsignificantlyreducegenerationfromcoalandnaturalgasandcutCO2emissionsNote:EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.LAC=LatinAmericaandtheCaribbean.HydropowerresourcesinLACandAfricacouldfacilitatetheintegrationofmoresolarPV,whiletheMiddleEast’srelianceonnaturalgaswouldalsohelptoprovidesystemflexibility.SoutheastAsiawouldfacethemostseriousintegrationchallenges,whichcouldbeeasedbyexpandinginterconnectionsandcross-bordertrade(IEA,2019).Inallemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,accesstofinanceandthereducedcostsofcapitalwouldbeessentialtobeabletotakeadvantageoftheopportunitytoaccelerateuptakeofsolarPV(IEA,2021a).IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings41IEA.CCBY4.0.1.4Thepathwaytoa1.5°Climitonglobalwarmingisverytough,butitremainsopenNetZeroRoadmap:AGlobalPathwaytoKeepthe1.5°CGoalinReach,theIEAupdatetothelandmarkNetZeroby2050Roadmap,waspublishedinSeptember2023(IEA,2023b).TheupdatedNetZeroEmissionsby2050(NZE)ScenarioisincorporatedinfullinthisOutlook.Itreachedtheconclusionthatthepathwaytonetzeroemissionsby2050hasnarrowedsincethefirstversionpublishedin2021,butthatitremainsfeasible.Inthissection,wehighlightfourreasonswhythispathwayremainsopenandlookatfourareasthatrequireurgentattentionifthepromiseofa1.5°Climitonglobalwarmingistoberealised.1.4.1FourreasonsforhopeCleanenergypoliciesaresteppingupManycountriesandanincreasingnumberofbusinessesarecommittedtoreachingnetzeroemissions.AsofSeptember2023,netzeroemissionspledgescovermorethan85%ofglobalenergy-relatedemissionsandnearly90%ofglobalGDP.Ninety-threecountriesandtheEuropeanUnionhavepledgedtomeetanetzeroemissionstarget.Moreover,governmentsaroundtheworld,especiallyinadvancedeconomies,haverespondedtothepandemicandtheglobalenergycrisisbyputtingforwardnewmeasuresdesignedtopromotetheuptakeofrenewables,electriccars,heatpumps,energyefficiencyandothercleanenergytechnologies.EVtargetshavedrivenamajortransformationintheindustrialstrategiesofcarandtruckmanufacturersinrecentyears,togetherwithfueleconomyandCO2emissionsstandardsintheEuropeanUnionandChina,andmorerecentlyintheUnitedStates.Similarly,electrictwo/three-wheelersandbuseshaveseensignificantuptakeinIndiaandotheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesthankstopolicysupport,increasingeconomiccompetitivenessandlimitedinfrastructureneeds.TheUnitedStates,throughtheInflationReductionActadoptedin2022,hasprovidedunprecedentedfundingtosupportdeploymentandreducecostsforarangeoflow-emissionstechnologies,notablycarboncapture,utilisationandstorage(CCUS)andhydrogen.Successivefive-yearplansinChinahaveprogressivelyraisedambitionsforsolarPVanddrivendownglobalcosts.OffshorewinddeploymentinEuropehasturnedintoaglobalindustry.CleanenergydeploymentisacceleratingfastCleanenergyinvestmentanddeploymenthaveincreasedrapidlyinresponsetothemarketsignalsandfinancialincentivesprovidedbygovernments,withmass-manufacturedtechnologiessuchassolarPV,windturbinesandEVsleadingtheway.Salesofresidentialheatpumpsandstationarybatterystoragearealsorisingfast.SincetheParisAgreementwassignedin2015,almost1terawatt(TW)ofsolarPVcapacityhasbeenaddedtotheglobalsystem–nearlyequivalenttothetotalinstalledelectricitycapacityintheEuropeanUnion.42InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Around40%ofthisdeploymentwasin2021and2022.Welloverhalfoftheelectriccarsontheroadworldwidehavebeensoldsince2021.Asaresult,solarPVcapacityadditionsarecurrentlytrackingaheadofthetrajectory1envisagedinthe2021versionofourNZEScenario.WenowestimatethatglobalmanufacturingcapacitiesforsolarPVandEVbatterieswouldbesufficienttomeetprojecteddemandin2030intheupdatedNZEScenario,ifallannouncedprojectsproceed.Thisprogressreflectsmajorcostreductionsinrecentyears:thecostsofkeycleanenergytechnologies–solarPV,wind,heatpumpsandbatteries–fellbycloseto80%onadeploymentweightedaveragebasisbetween2010and2022.Box1.2⊳CleanenergydeploymentisstartingtobendtheemissionscurveCleanenergydeploymentisstartingtobendtheemissionscurve,thankslargelytosolarPV,windpowerandEVs.ThesethreetechnologiescontributethebulkoftheemissionsreductionsintheWEO-2023STEPSrelativetoapre-ParisBaselineScenario(Figure1.15).SolarPVisprojectedtoreduceemissionsbyaround3Gtin2030,roughlyequivalenttotheemissionsfromallthecarsontheroadworldwidetoday.Windpowerisprojectedtoreduceemissionsbyaroundafurther2Gtin2030,andEVsbyaround1Gtmore.Thisisfarfromenoughtogetontrackfornetzeroemissionsby2050;indeedstayingonaSTEPStrajectoryto2030woulddefinitelyclosethedoortothe1.5°Climit.Butitiskeepingthepathwayopen.Figure1.15⊳GlobalenergysectorCO2emissionsinthepre-ParisBaselineScenarioandtheSTEPS,2015-2030GtCO₂45Pre-ParisBaselineOtherElectricvehicles40WindSolarPV35STEPS-202330202220302015IEA.CCBY4.0.SolarPV,windpowerandEVsreduceemissionsby6Gtin2030intheSTEPSrelativetothepre-ParisBaselineScenarioIEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings43WehavethetoolstogomuchfasterThekeyactionsrequiredtobendtheemissionscurvemuchmoresharplydownwardsby2030aremature,triedandtested,andinmostcasesverycosteffective.Morethan80%oftheadditionalemissionsreductionsneededin2030intheNZEScenariocomefromwell-knownsources:rampinguprenewables,improvingenergyefficiency,increasingelectrificationandcuttingmethaneemissions.IntheNZEScenario,triplingtheinstalledcapacityofrenewablesanddoublingtherateofenergyintensityimprovementsarecentraltothetransformationoftheenergysector.Figure1.16⊳Globalrenewablespowercapacity,primaryenergyintensityimprovements,andenergysectormethaneemissionsintheNZEScenario,2022and2030RenewablesIntensityimprovementsMethaneemissions6%15012000GWMt80004%100x3x2-75%40002%50202220302022203020222030IEA.CCBY4.0.Renewables,energyefficiencyandmethaneemissionsreductionoptionsareavailabletodayandcrucialtoreducingnear-termemissionsIEA.CCBY4.0.Triplingglobalinstalledcapacityofrenewablesto11000GWby2030providesthelargestemissionsreductionsto2030intheNZEScenario.Currenttrendsareencouraging;repeatingthegrowthrateseenoverthelastdecadewouldbesufficient,andcurrentpolicysettingsalreadyputadvancedeconomiesandChinaontracktoachieve85%oftheircontributiontothisglobalgoal.ThecontributionofsolarPVhasbeenrevisedupwardfromthe2021versionoftheNZEScenario,underpinnedbyasurgeinglobalmanufacturingcapacity,butarangeoflow-emissionstechnologiesisrequiredtoensurebalancedandsecuredecarbonisationofthepowersector.Doublingtheannualrateofenergyintensityimprovementby2030intheNZEScenarionotonlyreducesemissionsbutalsoboostsenergysecurityandaffordability,savingtheenergyequivalentofallworldwideoiluseinroadtransporttoday.Prioritiesvarybycountry,butthe44InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023keyimprovementsatthegloballevelcomefromupgradingthetechnicalefficiencyofequipmentsuchaselectricmotorsandairconditioners,fromefficiencygainsbroughtaboutbfryomeleucstirnifgiceantieorngyananddthmeastweriitaclhsmawoareyefrfofimciesnotlliyd.biomassuseinlowincomecountries,and1Furtherelectrificationofend-usesisapriority.EVsandheatpumpsarecentraltothis.SalesofEVsarealreadyincreasingfastenoughtoachievetheNZEScenariomilestoneoftwo-out-of-threecarssoldin2030beingelectric,andannouncedproductiontargetsfromcarmakerssuggestthatsuchanoutcomeiswithinreach.Heatpumpsalesrose11%globallyin2022,butmanymarkets,notablyintheEuropeanUnion,arealreadytrackingaheadoftheroughly20%annualgrowthrateneededto2030intheNZEScenario.Achievingtherapidgrowthinrenewables,efficiencyandelectrificationenvisagedintheNZEScenariodrivesdowndemandforfossilfuelsbymorethan25%thisdecade.However,itisalsovitaltoreduceemissionsfromthefossilfuelsthatcontinuetobeused.Cuttingmethaneemissionsfromfossilfuelsupplyby75%by2030isoneofthelowestcostopportunitiestolimitwarminginthenearterm,andthetechnicalsolutionsneededaretriedandtested.Withoutactiontoreducemethaneemissionsfromfossilfuelsupply,globalenergysectorCO2emissionswouldneedtoreachnetzerobyaround2045tomeetthe1.5°Climitgoal.TheworldisfindinginnovativeanswersThereisnoticeablylessrelianceonearly-stagetechnologiestoreachnetzeroemissionsintheupdatedNZEScenariothaninourfirstroadmapreportin2021.Atthattime,technologiesnotavailableonthemarket,i.e.atprototypeordemonstrationphase,deliverednearly50%oftheemissionsreductionsneededin2050toreachnetzero.Nowthatnumberisaround35%(Figure1.17).Progresshasbeendrivenbybothpublicandprivateeffortstofurtherdevelopandcommercialisenewcleanenergytechnologies,spurredbysupportivegovernmentpoliciesandthegrowingmarketprizeofthecleanenergyeconomy.EnergyR&DspendingbygloballylistedcompaniesexceededUSD130billionin2022,anincreaseof25%from2020,andcleanenergyventurecapitalflowsremainstrong,despitethemoredifficultmacroeconomicenvironment.Partofthisshiftisalsoduetoincreasedconfidenceindirectelectrificationasacost-effectiveapproach.Intheroadtransportsector,forexample,costreductionsandstandardisationforcommerciallithium-ionbatteriesinparticularhavestrengthenedthebusinesscaseforelectromobilityoverotheroptionsforalltypesofroadtransport.Overall,thedecarbonisationofroadtransportinthe2023NZEScenarioreliesaroundtenpercentagepointslessontechnologiesunderdevelopmentin2050thanwasthecaseinthe2021version,inpartbecauseofareductionintheshareofhydrogenfuelcellelectricheavy-dutyvehicles.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings45Figure1.17⊳ComparisonofCO2emissionsreductionsin2050relativetobaseyearbytechnologymaturityinthe2021and2023NZEScenario20%40%60%80%100%NZE-2021NZE-2023BehaviouralchangeMatureMarketuptakeDemonstrationPrototypeIEA.CCBY4.0.Emissionsreductionsby2050fromtechnologiesindemonstrationorprototypestagehavebeenreducedfromalmosthalfinthe2021NZEScenariotoabout35%in2023NZEScenario1.4.2FourareasrequiringurgentattentionScaleupcleanenergyinvestmentinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesCleanenergyinvestmentneedstoriseeverywhere,butthesteepestincreasesareneededinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChina(Figure1.18).From2015to2022,advancedeconomiesandChinatogetheraccountedforover95%ofglobalelectriccarandheatpumpsalesandnearly85%ofcombinedwindandsolarcapacityadditions.Therearesomebrightspotselsewhere,notablysolarinvestmentinIndia,butoverallcleanenergyinvestmentoutsideadvancedeconomiesandChinahasbeenstagnantinrealtermssince2015.Itwouldneedtoincreasebymorethansix-timesoverthenexttenyearstogetontrackfortheNZEScenario.However,therearesignificantobstaclestosuchascale-up,includingtighteningfinancialandfiscalconditions,highlevelsofgovernmentindebtedness,andhighcostofcapitalforcleanenergyprojects.Overcomingthesewillrequirestrongerdomesticpoliciestogetherwithenhancedinternationalsupport,includingmuchmoreconcessionalfundingtoimproveriskadjustedreturnsandmobiliseprivatecapitalatscale.Demandforenergyservicesto2050issettorisefastestinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChina,anditisvitalthatthisincreaseddemandismetinasustainableway.Atthemoment,thedistributionofcleanenergyuseacrosscountriesisevenmoreunequalthanforenergyconsumptionasawhole.AmongthecountriesforwhichIEAhascomprehensiveenergystatistics,thecurrentGinicoefficient3ofenergyinequalityis0.39forIEA.CCBY4.0.3TheGinicoefficientisameasureofinequalitytypicallyusedtomeasureincomeinequality,whichhasbeenadoptedinthissectiontoevaluateinequalityinenergyconsumption.1indicatesperfectinequality(whereonegrouporoneindividualconsumesorreceivesalltheresources),while0indicatesperfectequality.46InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023allsourcesofenergyconsumptionand0.46forcleanenergy.ThisunderlinestheneedtofindwaystoimproveinvestmentinemergingmarketanddevelopingcountriesotherthanChina,andtoraisethelevelofdeploymentofcleanenergytechnologiesinthosecountries.1Figure1.18⊳Averageannualcleanenergyinvestmentneedsbyregion/countryintheNZEScenario,2022-2050OtherEMDEChinaAdvancedeconomies2.01.51.0TrillionUSD(2022,MER)Cleanenergysupply2022Gridandstorage2026-30Low-emissionspower2046-50Energyefficiencyand2022end-use2026-302046-500.520222026-302046-50IEA.CCBY4.0.IEA.CCBY4.0.ThebulkofincreasedinvestmentincleanenergyisneededinemergingeconomiesotherthanChina;itrisesmorethansevenfoldinthesecond-halfofthe2040srelativeto2022Note:MER=marketexchangerate;EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Ensureabalancedmixofinvestment,especiallyininfrastructureAnetzeroenergysystemcannotrelyonlyonsolar,windpowerandEVs.Rapidgrowthintheuseofthesetechnologiesneedstobecomplementedbylarger,smarterandrepurposedinfrastructurenetworks,largequantitiesoflow-emissionsfuels,andtechnologiestocaptureCO2andstoreitpermanentlyortransformitintoclimateneutralfuels.Investmentsinmanyoftheseareasarelagging.Gridinfrastructureisacaseinpoint:thetimerequiredtoobtaingridconnectionscantakeseveralyearsandappearstobeincreasingratherthanshrinking.Thisishinderingcurrentprojectsandriskschokingoffnewones.IntheNZEScenario,transmissionanddistributiongridsexpandbyaround2millionkilometres(km)eachyearto2030,andaround30000to50000kmofCO2pipelinesareinstalledbythesameyear,togetherwithnewhydrogeninfrastructure.Investmentonthisscaledependsonexpeditedplanningandpermittingprocesses.Expanded,modernisedandcybersecuretransmissionanddistributiongridsarecriticaltoelectricitysecurityinaworldwheretheshareofsolarPVandwindinelectricitygenerationisrisingrapidly.Investmentisneededtoprovideadequatesystemflexibility,withoutwhichthereisariskofrisingamountsofsurplussolarPVandwindpowerattimeswhenoutputexceedsdemand.BatteriesanddemandresponseplayacriticalroleinmeetinghourlyChapter1Overviewandkeyfindings47variability,whiledispatchablelow-emissionscapacity–fossilfuelcapacitywithCCUS,hydropower,biomasspower,nuclear,andhydrogenandammonia-basedplants–playacriticalroleinsmoothingvariabilityacrossseasons.Maketransitionsresilient,inclusiveandaffordableCleanenergytransitionsrequiresignificantlyfewerextractiveresourcesinaggregatethanthecurrentenergysystem:foreveryunitofenergydeliveredin2050,theenergysystemintheNZEScenarioconsumestwo-thirdslessinmaterials,fossilfuelsandcriticalmineralscombined,thanitdoestoday.Butthatdoesnotremoveconcernsaboutenergyandmineralsecurity,indeedsomeconcernsmayintensifyastheenergysectoristransformedacrosstheworld.Asdemandforoilandgasdeclines,supplystartstobecomeconcentratedinlargeresource-holderswhoseeconomiesaremostvulnerabletotheprocessofchange.Therearealsopotentialriskstothesupplyofcriticalmineralsthatarevitaltothemanufactureofmanycleanenergytechnologies.Althoughcapitalspendingfordevelopmentofcriticalmineralssawa30%increasein2022andexplorationspendingroseby20%,announcedcriticalmineralminingprojectsarenotsufficienttomeettheneedsoftheNZEScenarioin2030.Bridgingthisgaprequiresastrongfocusoninvestmentinmining,processingandrefining,aswellasonrecyclingandtechnologyinnovation.Policymakersneedtopaycloseattentiontotheresilienceofcleanenergytechnologysupplychains.Forthemoment,theseexhibitahigherdegreeofgeographicalconcentrationthanfossilfuels,withChinahavinganotablystrongposition.Thispresentsanelevatedriskofdisruption,whetherfromgeopoliticaltensions,extremeweatherorasimpleindustrialaccident.Manycountriesarenowseekingtopromotemorediversepatternsofinvestmentandmanufacturingincleanenergysupply,includingforcriticalminerals.Findingwaystodosowhilecontinuingtoenjoythebenefitsoftradeisdifficultbutcrucial.Governmentsalsoneedtomakesurethattheprocessofchangeworksforeveryone,includingvulnerablecommunitiesandthosewhoselivelihoodsareaffectedbychangesinfuelsandtechnologies.Thisrequiresanactiveefforttohelppoorerhouseholdstomeettheupfrontcostsofcleanenergytechnologiesandthenbenefitfromtheirloweroperatingcosts(section1.6).Asanexample,adeepbuildingretrofit–anintegratedsetofenergyconservationmeasurestosignificantlyimproveoverallbuildingperformance–foranaveragesizehomecancostfourtoninemonthsofincomeforChineseorUShouseholdsinthe25thincomepercentile,comparedwithonetotwomonthsforhouseholdsinthe75thpercentile.IEA.CCBY4.0.FindwaysforgovernmentstoworktogetherAboveall,countriesneedtofindwaystomakethisacommon,unifiedeffort.Thisisvitaltoexpandfinancialflowstodevelopingeconomies,toacceleratecleanenergytechnologydevelopment,toensureequitableandcost-effectivecleanenergysupply,andtoensurethateffectivesafetynetsareinplaceincaseofdisruptions.Thepathwaytonetzeroemissionsismuchmorecomplexandcostlyinalow-trust,low-collaborationworld(section1.9).48InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20231.5Capitalflowsaregainingpace,butnotreachingtheareasofgreatestneed1Afteraperiodofstagnationinthelatterpartofthe2010s,energyinvestmentispickingup.TheIEAestimatesthatUSD2.8trillionissettobeinvestedindifferentpartsoftheenergysectorin2023,upfromUSD2.2trillionfiveyearsago.Almostalloftheincreaseinthelastfiveyearshasbeendirectedtocleanenergyandinfrastructure,whichnowaccountsforUSD1.8trillioninspending,comparedwitharoundUSD1trilliononfossilfuels(IEA,2023c).Allscenariosseeaneedforincreasedenergyinvestmentfromhistoriclevels.TotalenergyinvestmentrisestoUSD3.2trillionin2030intheSTEPS,USD3.8trillionintheAPSandUSD4.7trillionintheNZEScenario.AchievingthetransformationintheNZEScenariorequiresenergyinvestmentasashareofGDPtoincreasebyaroundonepercentagepointbetween2023and2030,buttheratiofallsbacktothecurrentlevelby2050(Figure1.19).Figure1.19⊳InvestmenttrendsasshareofglobalGDPbyscenario,2023-2050STEPSAPSNZETrillionUSD(2022,MER)55%44%33%22%11%2023203020402050203020402050203020402050CleanenergyFossilfuelsShareofGDP(rightaxis)IEA.CCBY4.0.AlargeincreaseincleanenergyinvestmentisprojectedintheAPSandNZEScenario,butfossilfuelinvestmentdeclinesandinvestmentrequirementsasashareofGDPfallafter2030IEA.CCBY4.0.Anincreasingshareofinvestmentisdirectedtocleanenergyinallscenarios.IntheSTEPS,theratioofinvestmentinfossilfuelstoinvestmentincleanenergytechnologiesrisesfrom1:1.8in2023to1:2.5in2030.IntheNZEScenario,itrisestomorethan1:10in2030.TheUSD2.5trillionincreaseincleanenergyinvestmentintheNZEScenarioto2030isfarlargerthantheUSD0.6trillionreductioninfossilfuelinvestmentoverthisperiod.Today’shigherinterestrateenvironmenthasincreasedfinancingcostsforenergy,andthishashadaparticularlylargeimpactonrelativelycapital-intensivecleanenergytechnologies.EmergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesinparticulararestrugglingwithrisingfinancingChapter1Overviewandkeyfindings49costsashigherbaseratespushupthecostofcapital.Acombinationofpolicyreformsandde-riskingmeasures,includingrevenueguarantees,firstlossguaranteesandcurrencyhedging,isneededtoaddressrealandperceivedprojectandcountryrisks.ThelargeincreaseincapitalinvestmentintheNZEScenarioispartlycompensatedforbyloweroperatingcoststhatfollowtheshiftawayfromfossilfuelstowardscapital-intensivecleantechnologies.Forfossilfuelimportingcountries,theshifttowardscleanenergyalsoimprovestradebalancesandenhancesenergysecurityastheshareofenergymetthroughdomesticallysourcedrenewablesstartstorise.IEA.CCBY4.0.1.5.1FossilfuelsContinuedinvestmentinfossilfuelsisessentialinallofourscenarios.Itisneededtomeetincreasesindemandovertheperiodto2030intheSTEPSandtoavoidaprecipitousdeclineinsupplythatwouldfaroutstripeventherapiddeclinesindemandseenintheNZEScenario.InpreviouseditionsoftheWEO,wewarnedofariskofunderinvestmentinaSTEPS-liketrajectoryfordemand,notingagapbetweentheamountsbeinginvestedinoilandgasandthefuturerequirementsofthisscenario.Butthesituationhasevolvedandthisisnolongerthecase.Oilandgasinvestmenthasriseninrecentyears,whilethebenchmarklevelofinvestmentneededin2030hascomedownwithimprovementsinthecapitalefficiencyoftheoilandgasindustryandwithadeclineintheprojectedlevelofoilandgasdemand.Russia’sinvasionofUkraineledtosomeshortfallsinsupply,butimmediateissueshavenowrecededbecauseRussianoilproductionandexporthasbeenmoreresilientthaninitiallyanticipatedandbecauseawaveofnewsupplyprojects,notablyforLNG,havereceivedthego-ahead.Asaresult,thelevelofinvestmentinoilandgasexpectedin2023isbroadlyequivalenttothelevelneededintheSTEPSin2030,andthefearsexpressedbysomelargeresource-holdersandcertainoilandgascompaniesthattheworldisunderinvestinginoilandgassupplyarenolongerbasedonthelatesttechnologyandmarkettrends.Therisksofoverinvestmentinfossilfuelshavealsoevolved,butintheoppositedirection.InvestmentinoilandgastodayissignificantlyhigherthantheamountsneededintheAPSandalmostdoublewhatisneededintheNZEScenario(Figure1.20).Thiscreatestheclearriskoflockinginfossilfueluseandputtingthe1.5°Cgoaloutofreach.Nonetheless,simplycuttingspendingonoilandgaswillnotgettheworldontrackfortheNZEScenario:thekeyistoscaleupinvestmentinallaspectsofacleanenergysystemtomeetrisingdemandforenergyservicesinasustainableway.Bothoverinvestmentandunderinvestmentinfossilfuelscarryrisksforsecureandaffordableenergytransitions.Anyassessmentoftheimplicationsofinvestmentneedstotakeintoaccountwhoisinvestingandtheefficiencyofthespending,andpolicymakersneedtobemindfulinparticularoftrendsthatcouldpointtoafutureconcentrationinsupplyorotherenergysecurityrisks.Whenitcomestotheoveralladequacyofspending,however,ouranalysissuggeststhattherisksareweightedmoretowardsoverinvestmentthantheopposite.50InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Figure1.20⊳Averageannualinvestmentinfossilfuelsupplyhistoricallyandin2030byscenarioBillionUSD(2022,MER)12502015-2022200STEPSAPSNZE15010050NorthAsiaMiddleEurasiaAfricaEuropeC&SAmericaPacificEastAmericaIEA.CCBY4.0.Continuedinvestmentinfossilfuelsisessentialineachscenario,butvariationsindecliningdemandmeanfarlessisneededintheAPSandNZEScenarioNote:C&SAmerica=CentralandSouthAmerica.IEA.CCBY4.0.1.5.2CleanenergyTheriseincleanenergyspendinginrecentyearshasbeenconcentratedinareaslinkedtocleanelectrification,inparticularsolarPVandotherformsofrenewablepower,andend-useelectrification,especiallyEVsandheatpumps(Figure1.21).Ifitismaintained,therateatwhichcleanenergyisgrowingwouldputaggregateglobalspendingin2030onlow-emissionspower,grids,storageandend-useelectrificationatlevelsconsistentwiththeneedsoftheAPS.Forsometechnologies,notablysolarPV,itwouldgobeyondtheinvestmentrequiredfortheNZEScenario.However,therearesignificantgapsinspendingonotherpillarsofcleanenergytransitions.Inparticular,investmentinenergyefficiencyremainswellshortofwhatisneededintheAPSandNZEScenario,despiterisingrecently.Investmentinlow-emissionsfuelsisanotherareawheremoreisneeded:itisincreasing,thankstoincreasedpolicysupportforareaslikelow-emissionshydrogenandCCUS,butfromaverylowbase.TheincreasesinspendingrequiredtomeetclimategoalsappearchallengingbutwithinreachforadvancedeconomiesandChina.Financeisavailableforcleanenergyprojects,andmanyofthemainrisks,includingthoserelatedtopermitting,nowappeartobeonthepolicyandregulatoryside.However,otheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesneedtotriplecleanenergyspendingfrom2022levelsby2030intheAPSandincreasethemoverfive-timesintheNZEScenario.Someofthelargestgapsareinenergyefficiencyandend-usedecarbonisation.Thisreflectsthefactthatmanylowerincomehouseholdsandbusinessesarestrugglingtomanagethehigherupfrontcostsofanumberofcleanenergytechnologies.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings51Italsoreflectstherelativeweaknessofpolicyframeworks,institutionalcapacityandenforcementinmanycountries.Theeffectofhighinterestratesonfinancingcostsisanothercomplicatingfactor.Figure1.21⊳Investmentincleanenergybyscenario,2030and205020502030AdvancedeconomiesPower2023eCleanenergysupplyEnergyefficiencySTEPSandend-useAPS20502030NZESTEPSAPSNZEEmergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies2023eSTEPSAPSNZESTEPSAPSNZE123TrillionUSD(2022,MER)IEA.CCBY4.0.Cleanenergyinvestmentgapsarelargestinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,especiallyforenergyefficiencyandend-usedecarbonisationNote:2023e=estimatedvaluesfor2023.Energyefficiencyinbuildingsstandsoutasalaggard.Theurbanpopulationisincreasingquicklyinmostdevelopingeconomies,andensuringthatnewbuildingsmeethighperformancestandardsforefficientheatingandcoolingpresentsahugeopportunitytolimitfuturestrainsonenergysupplyandemissions.However,relativelyfewemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomieshaveenergyefficiencybuildingcodes,withIndiabeinganotableexception.Higherstandardsandstrongerenforcementofstandardsfornewbuildingsplayacriticalroleinreducingenergyuseinbuildingsineachofthescenarios.IEA.CCBY4.0.1.6TransitionshavetobeaffordableTheglobalenergycrisisin2022catapultedcostsandpricesofenergytotheforefrontofthepoliticalagenda,andcountriesareunderstandablyconcernedaboutthecostsofthetransition.Forenergyusers,ameaningfulassessmentoftransitioncostsmuststartwithquantifyingtheadditionalspendingrequiredoncleanenergyoverconventionaloptions:forexample,thecostpremiumtopurchaseanEVoveraninternalcombustionengine(ICE)vehicle,ortoinstallaheatpumpinsteadofanaturalgasboiler.52InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Forsomeapplicationsandinsomepartsoftheworld,cleanenergytechnologiesarealreadycostcompetitivecomparedwithfossilfuels,meaningnetcostsarezeroorinsomecasesnegative,evenwithoutincentivesandothersupportforupfrontcosts.Inothercases,cost1gapsremain,andincentiveswillbecrucialtoacceleratetheadoptionofkeycleanenergymeasures.Thesecanbenarrowedeitherbyreducingtheupfrontandoperatingcostofcleanoptions,e.g.throughtechnologyandfinancialinnovationorgovernmentinterventionlikecleanenergysubsidies,orbychangingpricing,taxandsubsidyframeworksforfossilfuels,e.g.byremovingfossilfuelsubsidies,orincludingCO2costsorotherenvironmentalsurcharges.Suchpolicyinterventionshowevermustbecarefullydesignedandtargeted:politicalsupportforthetransitioncandissipatequicklyifhouseholdsorindustriesbeartoomuchupfrontcostwithoutseeingtangible,near-termbenefits.Supportmayalsodecreaseifinsufficientattentionispaidtothedistributionaleffectsofcleanenergysupportpoliciesorifthefiscalburdenongovernmentsisperceivedastoohigh.Inthissection,insightsfromthescenariosareusedtoexploretheseissuesfromtheperspectiveofhouseholds,industryandgovernments.IEA.CCBY4.0.1.6.1AffordabilityforhouseholdsTheenergycrisissqueezedbudgetsaspricessoaredin2022.Governmentinterventionsmoderatedtheextenttowhichhighercommoditypricesfedthroughtohigherhouseholdenergybills,neverthelesstherewereincreasesinnaturalgas,petrolandretailelectricitypricesinvariouspartsoftheworld.CleanenergytechnologiessuchasEVsorheatpumpshelpedshieldconsumersthathadadoptedthemfromfossilfuelpricespikes,andenergyefficientbuildingsandappliancesalsoprovidedsomeprotection.Heatpumps,energyefficiencyretrofitsandEVs–thethreemostimportantmeasuresthathouseholdscanadopttoacceleratecleanenergytransitions–arealreadynearlycostcompetitiveovertheirlifetimeintheSTEPSinadvancedeconomies,evenwithoutincentives(Figure1.22).Higherupfrontcostsremainabarriertoaccelerateduptake,butinsomemarketsevenupfrontcostsarereachingpriceparity.Air-to-airheatpumpscanbecheaperthannaturalgasboilersinmaturemarkets,forexample,andelectriccarssoldtodayinChinacostlessthantheirICEequivalentsonaverage,whilemoreenergyefficientairconditionersandrefrigeratorsdonotnecessarilycomewithhigherupfrontcostsinmarketsacrossAsia,AfricaandLatinAmericaandtheCaribbean.Evenwhencleanenergytechnologieshavehigherupfrontcoststhantheirfossilfuelequivalents,theyfrequentlygenerateenergybillsavingsovertheirlifetimebecauseoftheirloweroperatingcosts.However,thelifetimecostsofcleanenergyalternativesoftenremainhigherincountrieswherefossilfuelsubsidieshavestillnotbeenphasedout.Findingwaystomanagethehigherupfrontcostsofcleanenergytechnologieswillplayakeyroletoacceleratetheiradoption,especiallyinlowincomehouseholds.Limiteddisposableincomeandmoreconstrainedaccesstofinancingcanputhighercostoptionsoutofreachforalargeshareofthepopulation.Forexample,installingaheatpumpcancostuptoeightChapter1Overviewandkeyfindings53monthsofincomeforthosewithlowerincomes(seeChapter4,section4.4).Recentinterestratehikeshaveincreasedborrowingcostsforconsumersandareexpectedtocontributetoaslowingofhouseholdenergyefficiencymeasuresiftheypersist:afactorthatgovernmentswillneedtotakeintoaccountinconsideringhowtospeeduptheadoptionofcleanenergytechnologies.Figure1.22⊳AnnualunsubsidisedcostsofcleanenergyversusconventionaloptionsforhouseholdsinadvancedeconomiesintheSTEPSUSD(2022,MER)4000Fuelincludingtaxes3000Investment20001000RetrofitNoHeatGasElectricICEretrofitpumpboilercarcarIEA.CCBY4.0.Keycleanenergytechnologiesarealreadyroughlycostcompetitiveovertheirlifetime,thoughupfrontcostbarriersremainformostNotes:ICE=internalcombustionengine.Assumedlifetimesare25yearsforretrofits,16yearsforheatpumpsandnaturalgasboilers/furnaces,and12yearsforelectricandICEcars.CostsarebasedonarepresentativesampleofhouseholdsinGermany,Japan,UnitedKingdomandUnitedStates,withupfrontcostsfinancedataninterestrateof5%,startingin2024forfiveyears.Costsdonotreflectupfrontsubsidies.IEA.CCBY4.0.Energypricingplaysamajorroleindeterminingwhethercleanenergytechnologiesarecompetitiveintermsofcosts,andthefossilfuelsubsidiesthatpersistinanumberofcountriesareclearlyimportantinthiscontext.Inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,wherethebulkoffossilfuelsubsidiesexisttoday,phasingoutthesesubsidieswouldraisecurrenthouseholdenergybills,inaggregate,by70%.Fossilfuelsubsidiesdistortmarketsandareoftenultimatelypaidbyconsumersthroughhighertaxesorconsumerprices,especiallyinimportingregions.Theeffectsofsubsidyremovalonhouseholdspendingmeansthatthephase-outshavetobeplannedcarefullyandaccompaniedbysupportforthosethatneeditmost.Reformingenergypricingremainsessentialthough,notonlytorectifypricesignals,buttorealisetheeconomy-wideenergycostoptimisation.Theeconomy-widecostofsupplyingenergyusedinhouseholdsandforpersonaltransportinemergingmarketanddeveloping54InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023economieswasnearlyUSD1.8trillionin2022,ofwhicharoundUSD1trillionwasbornebyconsumers.Therestrepresentsfossilfuelsubsidiesbornebyotherentities,mostlyrgeovveenrnume.eInntsthanedNsZtaEteS-coewnnareido,enthteerperciosenso,meiyt-hweirdiencthoestfsoromfporforveidduincgedepnreircgeysodrecfolirngeontoe1USD1.6trillionin2030,25%lowerthaninSTEPS(Figure1.23).However,theremovalofsubsidiesandgradualintroductionofcarbonpricingmeanthatconsumerswouldpaymoreperunitofenergy,whilemodernenergyconsumptionincreasesinabsolutetermsdespiteefficiencygainsasrisingincomesallowforlargerresidencesandmoreappliances.Inaddition,householdsneedtoshouldertheupfrontcostsofcleanenergytechnologies.Figure1.23⊳Economy-widecostofhouseholdenergyinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesTotalenergycostInvestmentinenergyequipmentBillionUSD(2022,MER)200015001000500202220302030202220302030NZEElectrificationSTEPSSubsidiesSTEPSNZECarbonpricingEnergyspendingEnergyefficiencyOtherIEA.CCBY4.0.ThetotalcostofsupplyingenergyfallsintheNZEScenario,butvulnerableconsumersrequiresupporttomanagesubsidyphase-outandtheupfrontcostsofcleanenergyNotes:Subsidies=fossilfuelconsumptionsubsidiesbasedontheIEAprice-gapapproach.Energyspendingincludestransportenergyspending.Targetedsupportcouldhelpreducetheimpactofenergypricereforms,andwouldbeespeciallyimportantforlowincomehouseholds.Pricereformsshouldalsoaimtoendratestructuresthatpenaliseelectrificationofend-usesandtoincentivisetheprovisionoftime-varyingelectricitytariffs,forexampletoallowconsumerstochargeEVsovernightwhenelectricitydemandandpricesarelower.IEA.CCBY4.0.1.6.2AffordabilityforindustryIndustrywasmoreexposedtohighcommoditypricesduringtheenergycrisisthanhouseholds.Althoughsomelargerindustrieswereabletodrawoncontractingandhedgingstrategiestoguardagainstcommoditypricevolatility,inaggregateindustrypaidonaverageChapter1Overviewandkeyfindings55IEA.CCBY4.0.70%morefornaturalgasin2022thantheydidin2021,andaround25%moreforelectricity.Theprotectionprovidedforhouseholdsbygovernmentsinmanycountriesmeansthatindustryhadtocopewithmuchhigherpriceincreasesthandidhouseholds.Forenergy-intensiveindustries,adoptingcleanenergytechnologieswhilemaintainingcompetitivenessisoneofthedefiningchallengesoftheenergytransition.Manyefficiencyandcleanenergymeasuresinlightindustryarealreadycosteffective,notablyefficientelectricmotorsandheatpumpsforlow-temperatureheat(IEA,2022b).However,therearefewercost-competitivecleanalternativesforlarge,energy-intensiveindustriesthanforhouseholdsandlightindustry,andmanyoftheminvolvesignificantupfrontcapitalexpenditure.Moreover,manyofthecleanenergytechnologiesneededbyenergy-intensiveindustriesareatthedemonstrationphase.Thepositionisnotstraightforwardevenwherenewcleantechnologiesarefeasible.Manyenergy-intensiveproductssuchassteelorchemicalsaretradedinternationallyincompetitivemarketswithmarginsthataretooslimtoabsorbelevatedproductioncostsortoencouragefirstmoverstoadoptnewtechnologies.Thismeansthatthereisaneverpresentriskofindustrialrelocationifenvironmentalregulationsorenergypricesputfirmsininternationalmarketsatacompetitivedisadvantage.Relocationofbusinessesinthesecircumstancestojurisdictionswheresuchregulationsarenotimposeddefeatsthepurposeforwhichtheregulationswereintroduced,tosaynothingofthedamagedonetotheindustrialbaseinthecountrythatseesthecompaniesdepart.Thishaspromptedeffortstoimplementcarbonborderadjustmentmeasuresandsimilarpricingschemestoleveltheplayingfieldandmaintainthecompetitivenessofcompaniesandsectorsthatadoptdecarbonisingmeasures.Revenuefromsuchpricerectifyingmeasurescanberecycledtohelpmanagethehighermaterialinputcoststobusinesses,whicheventuallyreachtheendconsumerthroughhigherprices.Industry-ledinitiatives,suchastheFirstMoverCoalitionSteelCommitment,andinternationalagreementsoncollaborationonindustrydecarbonisations,liketheGlasgowBreakthroughAgenda,canalsoplayausefulrole.IntheNZEScenario,industryspendingonenergyreachesUSD4.3trillionin2030,around30%morethanintheSTEPS,eventhoughdemandismoderatedbymaterialandenergyefficiencyimprovements.Thehighercostsareduetonovelprocessesinenergy-intensiveindustry,whichinmanycaseshavehigherinputenergycosts,andalsotoincreasedcarbonpricesandthephasingoutoffossilfuelsubsidies.Pricingemissionsfromindustryremainsimportanttostimulatetheswitchtocleanenergybecauseithelpstoimprovethecostcompetitivenessofcleanenergytechnologiesandboosttheiradoption.Forinstance,carbonpricingandsubsidyreformraisetheproductioncostsforconventionalsteelintheNZEScenarioby2030andtherebynarrowthecostgapwithelectrolytichydrogen-basedproductionroutes.Nonetheless,electrolytichydrogen-basedsteelisstillatapremium.Insomecases,andespeciallythosewherethereiseasyaccesstoplentifulrenewablesourcesofenergy,thegapcanbeclosedby2030(Figure1.24).Inothercases,governmentsupportislikelytobenecessary,notleasttohelpcreatedemandfornearzeroemissionssteel,forexamplethroughpublicprocurement.Someimportantsteelmaking56InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023regions(suchasEurope,JapanandKorea)mightrequiresubsidiesforhydrogentobecostcompetitiveglobally.Figure1.24⊳Costofproducingsteelusingconventionalmethods1comparedto100%electrolytichydrogenbyscenario,2030USDpertonneofsteel1000800600400200EuropeAdvancedNorthLatinDevelopingNZEAsiaAmericaAmericaAsiaSTEPS100%electrolytichydrogen-basedproductionTypicalcurrentcostIEA.CCBY4.0.CarbonpricingandfossilfuelsubsidyphaseoutintheNZEScenarioraisethecostofsteelproduction,bringingitclosertothecostofelectrolytichydrogensteelproduction.Notes:Costdoesnotincludescrap-basedproduction.SeeAnnexCforregionaldefinitions.IEA.CCBY4.0.1.6.3AffordabilityforgovernmentsGovernmentsneedtotakeurgentactiontotackleclimatechange.Yet,manycountries,especiallyemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,aregrapplingwithincreaseddebt,inflationanduncertaingrowthprospects.Therearemultipledemandsonpublicbudgetstoaddressdevelopmentneeds,andsogovernmentsmustdesignfiscallyresponsiblepoliciesthatstrikeabalancebetweenspendingandrevenue-basedmeasures(IMF,2023).IntheNZEScenario,governmentsareexpectedtofinancearound30%oftheUSD4.2trillionofcleanenergyinvestmentspendingrequiredin2030.Thisincludesthroughlowcostloans,grants,directsupporttohouseholdsandindustries,andconcessionalfinance.Animportantquestionishowgovernmentsfinancethisinvestmentinascenariowhererevenuesfromtaxingtheproductionandconsumptionofoilandgasarefalling.IntheNZEScenario,publicrevenuefromtaxingCO2goessomewaytooffsetdecliningoilandgasrevenues,reductionsinfossilfuelsubsidiesprovidesomedirectreliefforgovernments,andtaxesontheuseofelectricityshoreuprevenuefromenergyconsumption(Figure1.25).However,governmentsaroundtheworldwillmaketheirowndecisionsaboutfundingbasedontheirspecificprioritiesandnationalcircumstances.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings57Figure1.25⊳Governmentrevenuefromenergyproductionandconsumptionfornetoilandgasimportingandexportingregionsbyscenario3500NetimportersNetexporters2500BillionUSD(2022,MER)1500Fossilfuelconsumptionsubsidies500OilandgasupstreamtaxandroyaltiesCarbonpricingOtherconsumptiontax:FossilfuelsElectricity02018-STEPSNZE20222030-5002018-STEPSNZE20222030IEA.CCBY4.0.Carbonpricingrevenuesandlowersubsidyburdensoffsetlowerfossilfuelrentsinexportingregions;fornetimporters,carbonrevenueprovidesfundsforcleanenergyinitiativesFornetoilandgasexporters,economicgrowthintheNZEScenarioisunderpinnedbyeconomicdiversificationratherthancontinuedrelianceonfuelexportsandroyalties.Thisenlargesthetaxableindustrialandconsumerbase,andhelpstominimisethetransferofrentsfromproducertoconsumercountriesthatapplyCO2taxation.ThelowerleveloffossilfuelsubsidysupportintheNZEScenarioandtaxesonconsumerspendingonelectricitytogetheroffsetdecliningrevenuesfromfossilfuelproduction,meaningthatthenetfiscalpositionintheNZEScenarioin2030iscomparabletothatofSTEPS.However,thisshiftrequirescitizensandbusinessestoabsorbmoreofthecostofenergydirectlythroughhigherupfrontinvestmentandhigherannualspendingonfuelsinthenearterm.Totheextentthatgovernmentsseetangiblesavingsonthepublicbalancesheetfromfossilfuelsubsidyremoval,thesecanbefunnelledintocleanenergysupportmechanismsorotherwiseusedtohelptopayforclimatechangeadaptationorothersustainablepublicspendinginitiatives,suchassocialsupportschemestohelpvulnerableconsumers.IEA.CCBY4.0.58InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20231.7RisksontheroadtoamoreelectrifiedfutureEblueicldtrinicgitsytodetmraannsdpoisrtp.rYoejte,cttheidsttroajinecctroerayseissnigontifsiectanintlsytoinnsee,catnodrsthraenregianrgefaronmuminbdeurstorfyraisnkds1thatcouldhamperthedeploymentofkeycleanelectricitytechnologies.Oneofthemostimportantriskstoprojectedgrowthinelectrificationistheavailabilityofcriticalmineralsforpowergenerationtechnologies,electricitynetworks,batterystorageandelectricvehicles.ThesetrendsandrisksarediscussedindetailinthisOutlookandsummarisedinthissection.Figure1.26⊳Globalelectricitydemandandshareofelectricityinselectedapplications,2022and2050TWh10000100%800080%600060%400040%200020%HydrogenIntensiveOtherAppliancesCoolingLight-dutyproductionindustriesindustryandcookingandheatingvehiclesElectricitydemand:20222050:STEPSAPSElectricityshareinconsumption(rightaxis):20222050STEPSAPSIEA.CCBY4.0.Electricityplaysanincreasinglyimportantroleinmanyend-usesNotes:Hydrogenproductionistheelectricityneededforitsproductionandtheshareofelectricityintotalenergyconsumedintheprocessofproducinghydrogen.Intensiveindustries(energy-intensiveindustries)includeironandsteel,chemicals,non‐metallicminerals,non‐ferrousmetals,andpaper,pulpandprintingindustries.Otherindustryincludestheremainingindustrialbranches,i.e.construction,miningandtextiles.Appliancesandcookingincludesstovesandovens,refrigerators,washinganddishwashingmachines,clothesdryers,brownappliances(relativelylightelectronicappliancessuchascomputersortelevisions)andotherelectricappliances(excludinglighting,cooling,cleaninganddesalination).Coolingandheatingincludespaceandwaterheating,andspacecoolinginbuildings.IEA.CCBY4.0.Theimportanceofelectricityrisesinmanyapplicationsovertheoutlookperiod(Figure1.26).Thebiggestconsumersofelectricitytodayarethebuildingsandindustrysectors,whichtogetheraccountforover90%ofglobalelectricityconsumption.Appliances,cooking,coolingandheatingaccountformostconsumptioninbuildings,andelectricitydemandincreasesforalloftheminourprojections,especiallyinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Industrialelectricitydemandcontinuestoriseasindustrialoutputincreases,mostlyinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,andaspoliciestoreduceemissionsencouragetheelectrificationofindustrialequipment.TransportisalsoamajorcontributortoprojectedChapter1Overviewandkeyfindings59electricitydemandgrowth,especiallyinadvancedeconomies.ThenumberofEVshasincreasedrapidlyinrecentyears,withelectriccarsalessurpassing10millionin2022.IntheSTEPS,electriccarsgainamarketshareof38%innewcarsalesby2030;intheAPS,thisrisestonearly45%.1.7.1ManagingrisksforrapidelectrificationTechnologiesessentialtocleanelectricitysystemsneedtoscaleuprapidlyforelectrificationtoproceedatthepacenecessarytomeettheenergyandclimatepledgesmadebygovernmentsaroundtheworld.However,therearerisksthatcoulddelayorimpedethedeploymentofsomeofthekeytechnologiesthatareneeded.Itiscriticaltohavesufficientpolicysupportandenablingregulatoryframeworks,efficientandtimelypermittingandcertification,whiledevelopingrobustandresilientsupplychains,fromrawmaterialstomanufacturingandconstructionandskilledlabourtoensuringaccesstofinancing.Reducingthecostsoffinancingandhavingpredictabilityforrevenuesorcostsavingsarealsoimportantforrapidelectrification.Eachtechnologyhasitsuniqueriskprofile,whichmaythreatenitsroleincleanelectrification(Table1.1).Progressinonetechnologymaydependonprogressinothers.Thelowertheserisksareacrosstheboard,thebetterthechancetodeliversecureandaffordabletransitions,callingongovernmentsandindustrytotakeaction.Table1.1⊳PrimaryrisksassociatedwithkeycleanelectrificationtechnologiesWindSolarPVNuclearBatteryDemandGridsElectricHeatstorageresponsevehiclespumpsRegulatoryandpolicyrisksRegulatoryframeworksMediumLowMediumMediumHighMediumMediumMediumPolicysupportLowLowMediumLowHighLowLowLowPermittingandcertificationMediumMediumHighLowLowHighMediumLowSupplychainrisksCriticalmineralsHighMediumLowHighLowMediumHighLowManufacturingHighLowMediumMediumLowLowLowMediumSkilledlabourMediumMediumHighLowLowHighLowMediumFinancialrisksCostsoffinancingHighMediumHighMediumLowHighMediumMediumMediumLowLowMediumMediumLowLowLowRevenueandsavingspredictabilityOverallrisksHighLowMediumMediumMediumHighLowMediumIEA.CCBY4.0.Note:Gridsreferstoelectricitynetworks,includingtransmissionanddistribution.60InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.Regulatoryandpolicyrisksincluderegulatorybarriers,inadequatepolicysupport,andslowplanningandpermitting.Regulatorybarrierscaninhibitthedeploymentoftechnologies,emitohreersduiprepcotrlytivoerobryeclfofescintigveofrfepgoutlaetnotriaylebnuvsiirnoensmsceanste.sDtehmatanddevreelosppoenrssec,oauldpoptuernstuiaelikneay1sourceofpowersystemflexibilityinthefutureisagoodexample(seeChapter4).Inmanymarketstoday,consumershavelittleincentivetoberesponsivebecauseshort-termpricesignalsfromelectricitymarketsarenottransmittedtothem.Alackofsufficientandcontinuouspolicysupportincreasesinvestoruncertainty,andthesuddenwithdrawalofpolicysupportcancausenascentmarketstocrash,asexperiencehasshownwithsolarPVandwindpowerinseveralmarketsoverthepast15years.Lengthycertificationandpermittingprocessesslowdeploymentandraisecosts,asseeninthewindindustry(IEA,2023b),intheconstructionofnewnuclearpowerplants(IEA,2022c)andintheexpansionofpowergrids(IEA,2023d).Therearefurtherpotentialsourcesofriskalongthesupplychainofcleanenergytechnologies.Somerelatetothefactthatboththesupplyofcriticalmineralsandthemanufactureofsolarmodulesandotherkeygoodsaredominatedbyasmallnumberofcountries(section1.9).Othersstemfromthedangerthatdemandwilloutpacethescalingupofmining,processingandmanufacturingcapacityalongthesupplychain,pushingupcostsandconstrainingcleanenergytransitions.In2021and2022,forexample,higherinputpricesforcriticalminerals,semiconductorsandbulkmaterialsresultedinpriceincreasesforkeycleanenergytechnologies(IEA,2023c).Anothersetofriskarisesfromtheneedforskilledlabouracrossthevariouslinksofcleanenergysupplychains.Tightlabourmarketsandashortageofskilledlabourhaverecentlycontributedtodisruptionsandprojectdelaysinpartsoftheelectricitysector,mostnotablyforoffshorewind(IEA,2022d).Shortagesofworkerswithspecificskillsarealsoslowingtheexpansionofpowergrids,theconstructionofnewnuclearpowerplantsandtheinstallationofheatpumps(IEA,2022b).Thelackofskilledlabourinsomesectorsunderlinestheneedforcollaborationandinvestmentineducationandtrainingprogrammestodevelopaskilledworkforcecapableofsupportingtheconstruction,andoperationandmaintenanceofkeycleanelectricitytechnologies.Financingrisksalsoneedtobeaddressed,includingthosethatrelatetothecostofobtainingfinance,tothedifficultyofpredictingfuturerevenueswhennewtechnologiesenterthemarket,andtomarketinstability.Long-termcontractingcanhelptoreducepriceuncertaintyfordevelopersofcleanelectricityprojects,andhighquality,highreliabilityproductsandcomponentscanhelptoreducetheriskofpoorperformance.Financingcostsforcleanenergyprojectshaverecentlybeendrivenupsignificantlybyrisinginterestratesinmarketsaroundtheworld,inparticularinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies(IEA,2023c).Increasesinfinancingcostshavethebiggestimpactonlarge-scaleprojectsinvolvingcapital-intensivetechnologiessuchasoffshorewind,gridsornewnuclearpowerplants,butrisinginterestratesalsoaffectconsumersthatrelyoncredittofinanceanEVortheinstallationofaheatpump.Theprogressofelectrificationwilldependonreducingthecostandimprovingtheavailabilityofcapital.ThisisofparticularimportanceforemergingmarketandChapter1Overviewandkeyfindings61IEA.CCBY4.0.developingeconomies,manyofwhicharecurrentlystrugglingtoraisethecapitalneededtofinancetheirtransitions(IEA,2021a).Itisimportanttohighlightthattheserisksarenotisolatedfromoneanotherbutareofteninterdependent.Alackofpolicysupportcan,forexample,makeaprojectlessbankablewhichraisesfinancingcosts.Permittingdelaysalsoraisefinancingcosts,whilethepoorerthanexpectedperformanceofanassetwilldepressrevenueorraisemaintenancecosts.Disruptionsatonestageofthesupplychaincanfeedthroughtoothertechnologies,sectorsandmarkets.Poorprogressforonetechnologycanalsonegativelyaffectothers.Delaysinextendingandreinforcingpowergrids,forexample,canalsoslowthedeploymentofrenewables,heatpumpsandEVs.Loweringrisksacrosstheboardisvital,whetherthoserisksrelatetoregulationandpolicy,cleanelectricitysupplychains,theavailabilityofskilledlabouroraccesstofinance.Thishighlightstheneedforaholisticapproachthatensureseverytechnologyisabletoplayitsroleindeliveringsecureandcost-effectiveelectrification.1.7.2CriticalmineralsunderpinelectrificationThetransformationoftheelectricitysystemandincreasingelectrificationleadstorisingdemandforcriticalminerals.Thesizeofthemarketforkeycriticalmineralsusedintheenergysectorhasdoubledoverthepastfiveyearsandgrowthisexpectedtopickupfurther(IEA,2023e).Ascleanenergytransitionsaccelerate,thefocuswillshiftfromthesupplyoftraditionalfuelstothesupplyofcriticalminerals(seeChapter4).However,theminingandprocessingofcertaincriticalmineralsisheavilyconcentratedgeographically,creatingasecurityofsupplyrisk.Longleadtimesforminesandtheassociatedinfrastructuremeanthatscalingupsuppliestakestime,raisingtheriskofsupplybottlenecks.Mitigatingtheserisksrequiresgovernmentsandindustrytoestablishamorediversifiednetworkofinternationalproducer-consumerrelationships,whileseekingtoensurethatsuppliesscaleupfastenoughtomeetgrowingdemand.Copper,rareearthelements,siliconandvariousbatterymetals,notablylithium,arecriticalmineralsforelectrification.Copperisusedextensivelyinelectricitytransmissionanddistributiongrids,butitsconductivepropertiesalsomakeitanessentialcomponentforlow-emissionspowergenerationtechnologiessuchassolarPVmodules,windturbinesandbatteries.Rareearthelements(REEs)areusedtomanufacturethepermanentmagnetsforthemotorsofdirectdriveandhybridwindturbines.Siliconisusedtomanufacturesolarpanels.Asthedeploymentofvariablerenewabletechnologiesincreases,theneedforstoragetechnologiestocomplementrenewableelectricityrisesrapidly.Lithium-ionbatteriesdominateinEVsandarethefastestgrowingelectricitystoragetechnologyintheworld,makinglithiumindispensableforelectrification(IEA,2021b).Intermsofabsolutevolumes,copperdominatestotaldemandforcriticalmineralsincleanenergyapplications,mostlyforuseintheelectricitysector:currentdemandofaround6Mtperyearrisesto11Mtby2030intheSTEPSand12MtintheAPS.However,lithiumseesthebiggestpercentageincrease:demandforlithiumforbatterystoragesystemsandEVsrises62InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023morethanfivefoldfromitscurrentlevelby2030intheSTEPSandnearlysevenfoldby2030intheAPS.Demandforcopper,siliconandREEsnearlydoublesto2030intheSTEPSandrisesalmost2.5-foldintheAPS(Figure1.27).1Figure1.27⊳DemandforcriticalmineralsforselectedcleanelectricitysupplyandelectrificationtechnologiesintheAPS,2022and2030Copper(Mt)Silicon(Mt)Rareearthelements(kt)Lithium(kt)155505001244040093303006220200311010020222030202220302022203020222030WindSolarPVOtherlow-emissionsgenerationGridsBatterystorageElectricvehiclesIEA.CCBY4.0.Electrificationraisesdemandforkeycriticalmineralsbytwo-toseven-timesby2030Notes:Mt=milliontonnes;kt=kilotonnes.Batterystorageislimitedtoutility-scalesystems.Thisunderlinesthatscalingupcriticalmineralssupplieswhilemakingthemmoresecureisakeychallenge.Morediverseandresilientcriticalmineralsupplychainsareanessentialelement.Theseneednotjusttodeliverareliablesupplyofcriticalmineralsbutalsotoapplyenvironmental,socialandgovernancestandardstotheirproductionandprocessing.Clearpolicycommitmentstoscaleupcleanenergytechnologiesareessentialtostimulatetheinvestmentsthatareneeded.1.8Anew,lowercarbonpathwayforemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesistakingshapeEmergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesfaceadiversesetofdevelopmentchallengesthatwilllargelyshapetheirregionalenergyandemissionspathways,andthatthereforehaveglobalimplications.Some64%oftheworldpopulationlivesinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChina.Thesecountrieshaveanaveragepercapitaincomethatisaroundone-fifthoftheaverageinadvancedeconomies,andtheylagonvarioussocio-economicandenergyindicators(Figure1.28).IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings63Figure1.28⊳Selectedsocioeconomicindicators,2022PercapitaUrbanisationAirconditionerCarincome100%ownershipownership60060160ThousandUSD(2022,PPP)ACsper100households4575%120450Carsper1000people3050%803001525%40150IEA.CCBY4.0.AdvancedeconomiesChinaOtherEMDEIEA.CCBY4.0.EmergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChinasignificantlytrailadvancedeconomiesonkeysocioeconomicindicatorsNote:PPP=purchasingpowerparity;ACs=airconditioners;EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.TheemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChinaincludeadiverserangeofcountries.Mostfaceenergy-relateddevelopmentchallengesthatbroadlyinclude:Toprovideuniversalenergyaccesstothosewhodonothaveelectricity(775millionpeopleinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChina)andthosewholackaccesstocleancookingfuelsandequipment(2billionpeopleinthesamegroup).UNSustainableDevelopmentGoal-7includesatargetfortheachievementofuniversalenergyaccessby2030,andthisiscurrentlyofftrack.Tofacilitatefurtherindustrialisationandthemodernisationofagriculture,bothofwhichrequireaccesstoaffordableandsecuresuppliesoftechnologiesandenergy.Theeconomicoutputfromindustryinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies(excludingChina)growsbyover30%by2030,andmorethandoublesby2050.Thecorrespondingenergydemandfromindustryrisesbyover20%by2030and65%by2050intheSTEPS.Todeliverplannedurbangrowthwithefficientmodernhousingthatiswellservedbypublictransport.Theurbanisationrate,builtspacepercapita,airconditionerownershipandcarownershipratesinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChinaarefarlowerthaninadvancedeconomies.By2050,anadditional1.8billionpeoplewillbelivinginurbanareasinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies(excludingChina),contributingtoadoublingofresidentialbuildingspaceandasharpriseinurbantransportdemand.64InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.Toplayabiggerpartinglobalenergysupplychains,includingthroughdomesticcleanenergytechnologymanufacturing.Fossilfuelsupply,cleanenergymanufacturing,ctoritvicaarylimngindeeraglreperso.dEumcteiorgninagndmraerfkientinagncdadpeavcietlioepsirnegmeacionngoemoigersaptohdicaayllayrceopnacretnicturalatreldy1vulnerabletosupplyshockswhilewealthierimportersarebetterplacedfinanciallytosecuretheirenergyandtechnologyneeds.Toreduceenvironmentalpollutantsfromenergyoperations.Airpollutionfromenergyuseisamajorconcern,leadingtoover5millionprematuredeathseveryyearinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies(excludingChina).Thechoicescountriesmaketoaddressthesedevelopmentchallengesandtheiremissionsreductioncommitmentswilltogethershapetheirfutureenergypolicychoices.Historically,economicdevelopmenthasbeenfuelledbycarbon-intensivetechnologiesandsourcesofenergyderivedfromfossilfuels,butthereareseveralfactorsthatnowpointtothepossibilityofamarkedlydifferentdevelopmentpathwayforemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.First,asdiscussedinthisreport,cleanenergytechnologycostshavebeenfallingacrossabroadsuiteofapplicationsworldwidefromcleanelectricitygenerationtocleanmobility,energystorageandenergyefficiency.Insomecases,suchaselectricitygeneration,cleantechnologiesarenowthelowestcostoptionsinmostpartsoftheworld.Asaresult,theynowofferpromisingavenuesforenergyandindustrialdevelopment.However,therearebarriersthatneedtobeovercomeforemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiestomakethemostoftheseopportunities.Theseareoftenlinkedtorisksthatcouldcallintoquestionthebankabilityofprojectsintheseeconomies.Theyincluderegulatoryandpolicyriskssuchasinconsistenttariffregimes,off-takerriskssuchasthefinancialweaknessofpowerdistributioncompanies,andlandacquisitionriskssuchaspermittingissues.Riskmitigationthroughappropriatepolicymakingandregulationhasakeyroletoplayinmanagingtheserisks,togetherwithfinancialinnovation.Second,theaccelerationofrenewableenergydeploymentisbeingcoupledwithincreasingelectrificationofeconomicactivity,evenindevelopingeconomies.Inthepastfiveyears,overhalfofthecapacityadditionsforelectricitygenerationintheemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChinaarerenewablesbased.Thismarksasignificantaccelerationcomparedtothepreviousdecade,whenrenewablesaccountedforaroundaquarterofcapacityadditions;furtheraccelerationislikelyinthefuture.IntheSTEPS,nearlytwo-thirdsofnewcapacityadditionsto2030arerenewables.By2050,electricitygenerationfromrenewablesincreasesfivefoldintheSTEPS,andoverten-foldinAPSby2050(Figure1.29).Increasingdeploymentofrenewablesisbeingaccompaniedinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesbyincreasedelectrification,withexpandinguseofEVsintransport,electricfurnacesandelectrochemicalprocessesinindustry,electriccookingappliancesinthebuildingssector,andelectricfarmequipmentsuchassolarpumpsinagriculture.IntheSTEPS,theshareofelectricityintotalfinalenergyconsumptionamongtheemergingmarketChapter1Overviewandkeyfindings65anddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChinaincreasesfrom15%tonearly25%by2050,whileintheAPSitreachesalmost35%inthesameperiod.Earlysignsofincreasedelectrificationarealreadyapparent.InIndia,forexample,overhalfofthree-wheelvehiclesalesarenowelectric,andinSouthAfricaelectricitynowmeets80%ofresidentialcookingenergydemand.Othercountrieslooksettoemulatetheseexamples:forexample,theshareofenergydemandforcookingmetbyelectricityinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesnearlydoublesby2050intheAPS.Figure1.29⊳Shareofrenewablesinpowergenerationandelectricityinfinalenergyconsumptionbyregionandscenario,2022-2050ShareofrenewablesinelectricitygenerationShareofelectricityinfinalconsumption100%75%50%25%20222030204020502022203020402050APSAdvancedeconomiesEMDEexcludingChinaSTEPSIEA.CCBY4.0.ShareofrenewablesinpowergenerationandelectrificationofeconomiesincreaseinallregionsNote:EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.IEA.CCBY4.0.Third,highfossilfuelimportdependence,fuelpricevolatilityandlargesubsidyburdensareconcernssharedbymanyimportingcountries;cleanenergytechnologiesofferscopetoreducethem.Whilethescalingupofcleanenergyalsonecessitatesimportsduetotheconcentrationofsupplychains,theuseofcleanenergyreducesrisksfrompricevolatilityoncethenecessaryinfrastructureisinplace.Allcountriesareaffectedbyfuelpricevolatility,butcountrieswithlowerincomessufferacutelymoreasaresultoftheirlimitedfiscalroomtomanoeuvreandlessaffordabilityamongconsumers.Overthepastdecade,emergingmarketanddevelopingcountrieshavecumulativelyspentUSD3.7trilliononoil,naturalgas,andcoalsubsidies(USD3.2trillionexcludingChina).Annualsubsidieshavefluctuatedsignificantlywithmovementsinenergyprices,withsubsidesnearlyfour-timeshigherin2022thanin2016,andtheunpredictablenatureoffuelpriceshasmadefiscalplanningdifficult.IntheAPS,USD3.8trillionisinvestedincleanenergyinfrastructureandequipmentcumulativelyto2030tokeepemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies(otherthanChina)onthepathwaytomeetlong-termcleanenergyambitions,andtheseinvestmentsdisplacefossilfueldemand,thereforereducingexposuretopricevolatilityandsupplyshocks.66InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Aswell,thereisincreasingrecognitionofthepotentialforcleanenergytechnologymanufacturingandcriticalmineralextractionandrefiningtoactasenginesofeconomicandemploymentgrowth.Aseffortstocreateanewglobalcleanenergyeconomygain1momentum,developingcountriesriskmissingoutonemergingeconomicopportunities.Someemergingmarketanddevelopingcountriesarealreadytakinginitialstepstoexpandtheirinvolvementintheunfoldingnewcleanenergyeconomy.Forexample,theIndonesiaBatteryCorporationwasestablishedbythegovernmentin2021tohelpthecountrybecomealeadingsupplierofEVbatteries,withatargettomanufacture140gigawatt-hour(GWh)batterycapacityby2030.Indonesiaistheworld’slargestproducerofnickel,anditaimstomoveupthevaluechainofmineralsupplies.IndiaimplementedtheProductionLinkedIncentivesprogrammetoincentivisetheproductionofsolarPVmodulesandbatteries.Itaimstostimulategreenfieldmanufacturingcapacityandtocreatenewjobs.Figure1.30⊳FossilfuelandCO2emissionsintensityofGDPbyregionandscenario,2022-2050FossilfuelintensityofGDPCO₂emissionsintensityofGDP3.6240GJperthousandUSD(2022,PPP)tCO₂permillionUSD(2022,PPP)2.71801.81200.96020222030204020502022203020402050AdvancedeconomiesEMDEexcludingChinaSTEPSAPSIEA.CCBY4.0.FossilfuelandCO2emissionsintensitiesinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChinafallbyhalfintheSTEPSandbyover70%intheAPSNote:GJ=gigajoule;PPP=purchasingpowerparity;tCO2=tonneofcarbondioxide;EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.IEA.CCBY4.0.Asaresultoftheseandotherrelatedfactors,notablyefficiencyimprovements,allglobalregionsseeincreasinguseofcleanenergytechnologiesandreductionsinthefossilfuelenergyandemissionsintensityofGDPacrosstheIEAscenarios.Thisimpliesthatlowerlevelsoffossilfuelsuppliesareneededovertimetogeneratethesameamountofeconomicoutput,andthatagivenlevelofeconomicoutputisassociatedwithfallingemissionsovertime.Therearesteepdeclinesinboththesemetricsacrossregions(Figure1.30).BothfossilfuelandCO2emissionsintensitiesfallbyhalfintheSTEPSby2050,andbyover70%intheAPSinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies(otherthanChina).Asaresult,evenasChapter1Overviewandkeyfindings67GDPnearlytriplesby2050inthisgroup,aggregateannualCO2emissionsrisebyonlyaquarterintheSTEPSandfallby30%intheAPS.Emergingmarketanddevelopingcountriesarenotboundtotrackthekindofemissionsintensivepathwaysthathavebeenfollowedinthepast.However,thedegreetowhichsuchcountriesareabletochartalternatepathwaysdependsontheamountofinvestmentincleanenergyandefficiencytechnologiesthattheyareabletoattract,andontheabilityofcountriesandhouseholdstopayupfrontcleanenergyinfrastructurecosts.Effectivepoliciesandregulatoryframeworkswillbeimportantinthiscontext,aswillthedevelopmentofdomesticfinancialmarketsandtheavailabilityofinternationalfinance.IEA.CCBY4.0.1.9Geopoliticaltensionsundermineenergysecurityandprospectsforrapid,affordabletransitionsGeopoliticsandenergyhavebeenintertwinedthroughoutthefossilfuelera:importershavecometodependonexportersforsupplies,andexportershavesimilarlycometodependonimportersforrevenue.Politicalandcommercialrelationshipsbetweenproducersandconsumershaveebbedandflowedasawaytomanagethesedependencies,butriskshavealsobeenmitigatedbyopeninternationalenergymarkets,initiallyforoil,morerecentlyalsofornaturalgas.Well-functioningmarkets,alongsidesafetynetssuchassparecapacityheldbykeyproducersandtheIEAco-ordinatedsystemofoilstocks,havehelpedcountriestomanageshiftsinsupplyanddemand:theyhavealsoprovidedabufferagainstdisruptionscausedbyextremeweatherorgeopoliticalevents.Tradeprovidesaccesstoalargebalancingareatomanageshiftsinsupplyordemand:thisinsightisalsobecomingincreasinglyvaluableforelectricitysecurityininterconnectedandrenewables-richmarkets.Russia’sinvasionofUkraineprovidedasterntestoftheresilienceoftoday’senergysystemtogeopoliticalshocks.ThepricespikesthatfollowedcutstogassupplyfromRussiawerecertainlyverydamaging,buttheattemptbyRussiatousegassupplyforpoliticalleveragefailed.Russiahaslostitslargestcustomer,shreddeditsreputationasareliableexporterandcreatedincentivesforconsumerstoconsideralternativestonaturalgas.Thisisreflectedinourprojections:theglobalenergycrisishaspromptedasignificantdownwardrevisiontonaturalgasdemandintheSTEPSandtoRussiangasexports(section1.10).Therecentcrisishasshownhowgeopoliticaleventscanaffecttheenergysector.However,therelationshipworksbothways:changesinenergymarketscanalsoshapegeopolitics.Asenergytransitionsproceed,theyshiftdemandacrossfuelsandsourcesofelectricityinwaysthateventuallyloosenthegripoffossilfuelresource-holders.Theprocesswillbealongoneandfossilfuelproducersremaininfluential.Indeed,theshareoftheOrganizationofOilExportingCountries(OPEC)inglobalsupplyrisesovertimeinourNZEScenarioasdemandfalls.Butinexercisingthisinfluencetheyreduceit,becauseconsumershaveanincreasingrangeofmaturecleanenergyoptionsthatbecomemoreattractiveasaresult.Energytransitionsdonot,however,meananendtogeopoliticalrisks.Traditionalrisksaroundfossilfuelsupplyevolve,buttheydonotdisappear.Transitionscouldbedestabilising68InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023forfragileproducingstatesthatfailtodiversifyawayfromhighdependenceonhydrocarbonrevenues.Inthemeantime,newgeopoliticalrisksanddependenciesariseincleanenergysupplychains(BordoffandO’Sullivan,2023).Andbothtraditionalandnewsecurityrisksare1worsenedinamorefragmentedinternationalsystemcharacterisedbyrivalriesandlowco-operation.Theworldcanillaffordthesetensionsifitwantstogetontracktolimitglobalwarmingto1.5°C.Astheaccelerationincleanenergydeploymentinrecentyearsshowed,periodsofdisruptionandhighfossilfuelpricescangiveadditionalmomentumtotransitions.Butthisisaverycostlywaytochangethesystem.ThelatestnumbersfromtheIEAGovernmentEnergySpendingTrackershowthatoverUSD1.3trillionhasbeenallocatedbygovernmentsforcleanenergyinvestmentsupportsince2020(IEA,2023f).However,sincethestartoftheenergycrisis,governmentshavealsoallocatedsomeUSD900billiontoshort-termconsumeraffordabilitymeasures.Inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,governmentshavededicatedmoretoconsumeraffordabilitymeasures(USD140billion)thantocleanenergyinvestmentsupport(USD90billion).Movingfromcrisistocrisisisnowaytomanagethecleanenergytransition.Thereislimitedscopetoincorporategeopoliticalshocksintoourlong-termOutlookscenariostructure,giventhattheireffectsanddurationarebytheirnatureunpredictable.Nonetheless,thebaselineexpectationisforafuturemixtureofrivalryandcollaboration.ElementsofgeopoliticscomethroughintheSTEPS,especiallyinrelationtothepositionofRussiaininternationalenergytrade,butthehopeisthatco-operationoncleanenergycanberingfencedfrombroadergeopoliticaltensionssoastoallowrapidprogresstowardsglobalnetzeroemissionsinlinewiththeNZEScenario,whichdependsonco-operationbetweencountries:withoutthis,itsobjectivesfalloutofreach.Thenextsectionexploreshowtheenergysectormightfareinaworldthatislowerontrustandloweronco-operationthanourbaselineexpectations.Itconsidersinparticularhowgeopoliticaltensionsmightaffecttheoutlookbothforcleanenergyandforfossilfuels.IEA.CCBY4.0.1.9.1Cleanenergyinalow-trustworldOpportunitiestoproducelow-emissionsenergycostcompetitivelyarefarmorewidelydistributedaroundtheworldthanisthecaseforfossilfuels.Itwouldthereforebenaturaltoassumethat,asalargelydomesticsourceofenergy,renewableswouldfarebetterinamorefragmentedinternationalcontext,especiallyincountriesthatrelyonimportedfuels.Theenergycrisisin2022providessupportingevidenceforthis,withdeploymentofrenewablepowerandimprovementsinefficiencyintheEuropeanUnioncoveringnearly20bcmor25%ofthesupplygapleftbyRussia’sactions.Domesticallyproducedcleanenergycanclearlybeanassetattimesofgeopoliticalstress.However,whilerenewableresourcesarewidelydistributed,thesameisnottrueforcleanenergysupplychains,whichareheavilyconcentrated.IEAanalysisfromthemostrecentEnergyTechnologyPerspectives2023bringsoutclearlythatthethreelargestproducercountriesaccountforatleast70%ofmanufacturingcapacityforkeymass-manufacturedChapter1Overviewandkeyfindings69technologies–wind,batteries,electrolysers,solarpanelsandheatpumps–withChinadominantineach(IEA,2023g).Forcriticalminerals,resourcesarespreadquitewidelybutcurrentminingactivitiesarehighlyconcentrated,muchmoresothanisthecaseforfossilfuelsupply(Figure1.31).Chinahasinvestedheavilyinmidstreamrefiningandprocessingandhasaverystrongpositioninboth.Figure1.31⊳Averagemarketsizeandlevelofgeographicalconcentrationforextractionofselectedcommodities,2020-2022Marketsize(billionUSD)10000Naturalgas1000Oil100Copper10NickelLithium1Cobalt0%RareearthPlatinumelements10%20%30%40%50%60%70%80%90%100%Marketsharebytop-threeproducercountriesIEA.CCBY4.0.MarketsforcriticalmineralsaresmallerandmoreconcentratedthanthosefortraditionalhydrocarbonresourcesIEA.CCBY4.0.Overall,China’sinvestmentincleanenergysupplychainshashelpedbringdowncostsworldwide,withmultiplebenefitsforcleanenergytransitions.Thereisalsoadistinctiontobemadebetweenenergysecurityhazardsinfuelmarkets(whichaffectallconsumersusingthefuel)andthoseincleanenergysupplychains(whichaffectonlytheflowofnewmanufacturedproducts).Nonetheless,oneoftheclearestlessonsfromthehistoryoftheenergysectorstillstands:highrelianceonsinglecountries,companiesortraderoutesmakesthesystemvulnerabletounexpectedevents,betheyrelatedtothepolicychoicesofanindividualcountry,naturaldisasters,technicalfailuresorcompanydecisions.Theserisksareinevitablyheightenedattimesofgeopoliticalstress.Alow-trustworldcouldcreateincentivestorelymoreondomesticallyproducedcleanenergy,buttheseincentivescouldbeundercutinpracticebyareluctancetorelyheavilyonimportedtechnologies,orshapedbyapreferenceforthosetechnologiesthatrequirethefewestimportedelements,orthosewheretherisksofsupplychaindisruptionsseemlowest.Supplyofcriticalmineralscouldbeaparticularpressurepoint,sincenowtherearerelativelyfewbuffersinplacetocopewithinterruptionsordisruptions,marketsarethinlytradedandoftenopaque,andrestrictionsontradehaveriseninrecentyears.70InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Giventhehighdegreeofconcentrationinenergysupplychains,therearejustifiablereasonsforcountriestoseektoincreasetheresilienceofcleanenergysupplychainsthroughtinhdautstthriisalpproocliecisesscaonudldsutipppoovretrfoinrtboromaudcehrmsuoprpelywdidiveesrpsriteya.dThbearrriisekrsintoatlroawd-etrausstcowuonrtlrdieiss1prioritiseautonomyovermanageddependence,andinsodoingaddcosts,complexityandtimetotheprocessofchange.Barrierstotradeofthiskindwouldalsolimitthescopeforcost-effectivedevelopmentofnewcleantechnologymarkets,whichdependheavilyontechnologylearningandcollaborationsacrossnationalborders.Withoutco-operation,somecountries–especiallyemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies–couldstruggletogainastakeinthenewcleanenergyeconomy,andsomeofthecleantechnologymarketsthatareneededforanetzeroemissionsenergysystemcouldtakemuchlongertogainmomentum,orfailtotakeoffatall.IEA.CCBY4.0.1.9.2Fossilfuelsinalow-trustworldFollowingRussia’sinvasionofUkraine,tensionsintheMiddleEastunderscorethepotentialrisksthatcontinuetofaceoilandgassupply.TheSTEPSprojectionshighlightthatmanyemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,notablyinAsia,seeasignificantincreaseinoilandgasimportsbothintermsofvolumeandcost(Figure1.32).Alow-trustworldwouldcreateincentivestolimitthesevulnerabilitiesinfavourofresourcesthatareavailabledomestically.Asnoted,thiscouldcreatesomeupsideforcleanenergy,withcaveats.Butitcouldalsokeepcoalinthemixforlongeraswell.Whereresourcesareavailable,importingcountriescouldalsotrytomanagevulnerabilitiesbyprioritisingdomesticproductionofoilandgas,includingbygreenlightingnewprojects.Whilethismightpotentiallyprovidesomesupportatthemargin,itisunlikelytodeliveradditionalproductionquickly(withtheexceptionofsomeshort-cycledevelopmentssuchasshale).Historicallyithastakenwellovertenyearsonaverageforaconventionalprojecttomovefromlicensingtofirstproduction.Moreover,suchanapproachwouldcomewithariskofpushingglobalproductionbeyondthe1.5°Cthreshold,andofnewprojectsbecomingloss-makingiftheworldgetsontracktokeepglobalwarmingbelow1.5°C.Theoutlookfornaturalgaswouldfaceadditionaluncertaintiesinaworldofhighgeopoliticaltensions.AsignificantnewwaveofLNGexportfacilitiesisunderconstruction:250bcmperyearofliquefactioncapacityisscheduledtostartoperationbytheendof2030,whichisequivalenttoalmosthalfofglobalLNGsupplyin2022.TheUnitedStatesandQataraccountfor60%oftheadditionalLNG,withAsiatheintendedmarket:Chinaalonehascontractedforanadditional85bcmofgassince2022.Gasmarketshavebecomeincreasinglydeepandliquidinrecentyears,adevelopmentthathasunderpinnedinvestorconfidenceandanenhancedabilitytorespondtoshocks.Areversalofthistrendwouldreduceoptionalityandsecurity.Oilmarketstoocouldseetradebeingfurtherdeterminedbypoliticalconsiderationsandrelationships,asproducersattempttotieinconsumersandbuyersseekmoresecurity.Thiswouldcomeatacosttoefficiency,andcouldlockinfossilfueluseandrelatedCO2emissions.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings71Figure1.32⊳ValueofdomesticproductionandimportbillsforfossilfuelsinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesinAsiaexcludingChinabyscenario,2010-2050800STEPSAPSBillionUSD(2022,MER)4000-400-8002020203020402050201020202030204020502010Netimports:CoalNaturalgasOilDomesticproduction:CoalNaturalgasOilIEA.CCBY4.0.IncreasingfossilfuelimportbillsindevelopingAsianeconomiesimplysignificantvulnerabilitytoglobalenergypriceandmarketvolatilityIEA.CCBY4.0.1.9.3RisksofnewdividinglinesTherearemajorhazardsfortheenergyoutlookinamorefragmentedanddividedworld.Suchaworldcouldwellreducetheabilityofcountriestotackleclimatechange,toensureenergysecurityandtorespondtoahostofotherenergy-relatedchallenges.Aparticularriskisthatdividinglinesthatdisadvantageemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiescouldbecomeentrenched,constrainingtheirabilitytoaccessfinanceandtoparticipateinglobalsupplychains.Competitiontosecurecriticalmineralsuppliescouldalsomitigateagainstthepushtoraisestandards,andcouldresultinmoretacitacceptanceofthekindofpoorlabourpracticesandexploitativeresourceextractionpoliciesthathaveimpoverishedcountriesinthepast.Withoutinternationalco-operation,thechancesoflimitingglobalwarmingto1.5°Crecedeoverthehorizonandoutofsight.Theworldneedstoembracearules-basedtradingsystemifenergytransitionsaretosucceed.ItwillnotbepossibletoexpandcleanenergyinlinewiththeNZEScenarioifcountriesprioritiseself-sufficiencyoverintegrationandtrade.Norwillitbepossibletopreventtheroadaheadfromlookingincreasinglybumpyandperilousfromanenergysecurityperspectiveifcountriesstarttolosethebenefitsofinterconnectedmarketsasawayofcopingwithshiftsinsupplyanddemandandofridingoutunexpectedshocks.Inthesecircumstances,aworseningclimatecoulditselfposeanincreasinglysignificantthreatinthecomingdecades,wideninganyfracturesininternationalaffairsintheprocess.Thisallpointstothevitalimportanceofredoublingcollaborationandco-operation,notretreatingfromit.72InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20231.10Asthefactschange,sodoourprojectionsTheSTEPSillustratesthedirectioninwhichcurrentpolicysettingsaresteeringtheenergy1sectorbasedonasector-by-sectorassessmentofexistingpoliciesandannouncements.Thistrajectoryisupdatedonanannualbasisinlinewithchangesinpolicysettings,marketconditionsandtechnologydevelopments,anditisinstructivetolookathowtheprojectionshaveevolvedovertime.AnycompanyorpolicymakerconsideringourOutlookneedstobearinmindthedynamicnatureofthescenario:forexample,ifacompanychoosestoalignitsinvestmentswithSTEPS,itneedstobeawarethatthisisamovingtarget.Figure1.33⊳DifferencesinglobaltotalenergydemandbyfuelandsectorintheWEO-2023-STEPScomparedtotheWEO-2022-STEPS,2030CoalRenewablesOilElectricityIEA.CCBY4.0.6OtherOthertransportEJ3CarsOtherindustry0Ironandsteel,cementPowerNetchange-3-6IEA.CCBY4.0.InthisOutlook,thepowersectortapssignificantlymorerenewablesanduseslesscoalthanintheWEO-2022-STEPS,plusroadtransportiselectrifiedfasterChangesinstartingconditionssincetheWorldEnergyOutlook-2022(WEO-2022)havehadamaterialimpactontheoutlookforenergy(Figure1.33).Asdiscussedinsection1.1,this2023Outlookisthefirsttimethatascenariobasedonexistingpolicysettingsseesapeakindemandforeachofthefossilfuelsbefore2030.SomeofthekeychangesinthisOutlooksincetheWEO-2022are:Fastergrowthinelectriccarsales.InthisOutlook,theSTEPSprojectionsshowmorethan220millionelectricpassengercarsontheroadin2030,a20%increaseonthenumberintheWEO-2022.Thisincreasecutsoildemandin2030byaround1mb/dandboostselectricitydemandfromroadtransportby165TWh.Continuedmomentuminrenewablesdeployment.Higherinterestratesandnear-termsupplychainchallengescreatedifficultiesforsomenewprojects,butoverallourChapter1Overviewandkeyfindings73IEA.CCBY4.0.projectionsshowfurtheraccelerationindeployment.SolarPVinparticularrisesmorequicklythanintheWEO-2022,reflectingstrengthenedpoliciesinanumberofkeymarketsandamplesolarPVmanufacturingcapacity(section1.3).Thisresultsinlowergenerationfromcoalandnaturalgas.SlowereconomicgrowthandconstructionactivityinChina.Thishasanimpactontheprojectionsforallfuels,butithasaparticulareffectoncoaldemandinChina,whichisnearly100Mtcelowerin2030thanintheWEO-2022,withlargereductionsinpowerandthesteelandcementsectors(section1.2).Year-on-yearrevisionsareimportant,butitisalsousefultotakealookathowprojectionshaveevolvedoveralongertimeframe.SomeofthelargestchangesintheSTEPSoverthelastfiveyearshavebeeninsolarPVandwindgenerationand,particularlysincetheglobalenergycrisis,innaturalgasdemand.Thesearethefocusofthefollowingsections.Wealsoincludeinsightsonhowthetechnologymixtoreachnetzeroemissionsby2050hasevolvedintheNZEScenariosinceitwasintroducedin2021(Box1.3).Box1.3⊳Howdoesthe2023NZEScenariodifferfromthe2021version?TheupdatedNetZeroby2050Roadmap,releasedbytheIEAinSeptember2023,achievesthesameoutcomeastheoriginalversionfrom2021–limitingtheriseinglobalaveragetemperaturesto1.5°C–butthetrajectoryforemissionsandtherespectiverolesofdifferentfuelsandtechnologieshavechanged(IEA,2023b).Thisreflectsadifferentstartingpointforthescenarioaswellasbiggercontributionsfromtechnologiesthathavemadegoodprogressinrecentyearsandsmalleronesfromthosethathavemademorelimitedprogress.Since2021,demandforfossilfuelshasrisen.Thispartlyreflectspost-pandemiceconomicgrowthandtheeffectsoftheglobalenergycrisis,butitisalsotheresultofacollectivefailuretomovemorequicklytoscaleupcleanenergyinvestmentinefficiencyandsupply.Thismeansthattotalenergydemand,fossilfueluseandemissionsin2030arehigherthaninthe2021versionoftheNZEScenario.Coaldemanddeclinesrapidly,butin2030itisnonethelessabovethelevelsinthe2021NZEScenario.Thisreflectsanattempttoprovideamoremanageableandequitablenear-termpathwayforemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,whichdominateglobalcoaluse,butitalsostemsinpartfromtheenergysecurityconcernsaroundnaturalgassparkedbyRussia’sinvasionofUkraine.Thischangemeansthatthepathtoachievingnetzeroemissionsby2050inthe2023NZEScenarioisasteeperonethaninthe2021versionandrequiresmoretobedoneafter2030,butthepathremainsopen.Thebalanceofcleanenergytechnologiesusedtoachieveemissionsreductiongoalshasalsoshifted.SolarPVtakesamoreprominentroleinthe2023NZEScenario,thoughreductionsinprojectedwindcapacityadditionsmeanthatthecombined40%shareofwindandsolarPVintotalgenerationin2030isverysimilartothatprojectedin2021.74InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023ThisreflectsthesurgeinsolarPVinstallationsandmanufacturingcapacitysincethe2021report.TheriseinsolarPVgenerationleadstoaneedforadditionalstationarybatterystoragetoensuresecurityofsupply.1Electricityandelectrificationplayevenmoreprominentrolesinthe2023NZEScenariothantheydidinthe2021version.ThisreflectsasignificantincreaseinEVsalesandprogressinscalingupEVmanufacturingsupplychains.Italsoreflectsacceleratedprogressinheatpumpdeploymentinbuildingsandrisingmarketconfidenceintechnologiessuchas100%electrolytichydrogen-baseddirectreducedironproduction.Near-termdeploymentisslowerforsometechnologies,notablywind,hydrogenandCCUS.Thisreflectssupplychainconstraints,delaysinscalingupprojectpipelinesandrelatedinfrastructure,andsluggishprogressinthedevelopmentofmarketframeworksforlessmaturetechnologies.Forsomeofthesetechnologies,thedownwardrevisionisbasedonrecentinvestmenttrendsfromtechnologymanufacturerscomparedwithinvestmentinotherlow-emissionsalternatives.So,forexample,the2023Roadmapforeseesareducedroleforhydrogen-fuelledtrucks.Theoutlookfornaturalgasinthe2023NZEScenariohasalsochangedsincethefirstversionin2021.Inthe2021Roadmap,naturalgasusefellto1750bcmin2050;inthisOutlook,itfallsto920bcm.Mostofthis830bcmdifferencein2050isbecauseoflowerprojectedhydrogenproductionfromnaturalgaswithCCUS,withalargerrolenowprojectedinsteadforhydrogenproductionviaelectrolysis.1.10.1SolarPVandwindgenerationTheSTEPSprojectionsforsolarPVandwindgenerationto2030haveincreasedsubstantiallyinsuccessiveeditionsoftheOutlooksince2019(Figure1.34).Fourmainfactorshavebeenatplay:Policies:ThenumberofcountrieswithpoliciesthatsupportexpansionofsolarPVandwindhassteadilyrisen,andnowstandsatover140.Atthesametime,policyambitionsandrelatedsupporthavebeenratchetedupmanytimesinmajormarkets,includinginChina,EuropeanUnion,India,JapanandUnitedStates.Costreductions:Between2010and2022,thelevelisedcostofelectricityfellbyabout90%forsolarPV,70%foronshorewindand60%foroffshorewind.Althoughtherehasbeenariseincostsinrecentyears(section1.3)whichhascreateddifficultiesinparticularforwindpowerinsomeadvancedeconomies,thesecostreductionshavelargelyfollowedanticipatedlearningrateslinkedtothescalingupofdeploymentandtechnologyinnovation.Ingeneral,policysupportandcostreductionshavecreatedavirtuouscycle:increasedpolicysupportraisedthelevelofdeployment,whichledtocostreductions,andthosecostreductionshaveledtoadditionaldeployment.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings75Manufacturingcapacityandindustrialpolicies:IEAprojectionsnowfullyaccountfordevelopmentsincleanenergysupplychains,whichinsomecaseshavefaroutpacedactualdeploymentandcreatedanopportunityforfurtherrapidincreases,notablyforsolarPV(section1.3).Financingconditions:CostofcapitalforsolarPVandwindpowerisespeciallyimportantbecauseupfrontcapitalcostsaccountforthemajorityoftheirlifetimecosts.Triedandtestedpolicyandregulatoryframeworkshavehelpedreducefinancingcostsbyprovidingoperatorswithahighdegreeofrevenuecertainty,usuallythroughlong-termcontracts.Againstthisbackdrop,today’shigherborrowingcostsareacauseforconcernastheycomplicateprojecteconomicsandcouldtiltcostcalculationsbacktowards(oftenpolluting)technologiesthathavelowerupfrontcostsbutlockinlong-termexpenditureforfuel.ThesefactorshavebeenverypositiveoverallfortheexpansionofwindpowerandsolarPV,andhelptoexplainyear-on-yearincreasesinprojecteddeployment.However,thegrowthinwindandsolarPVgenerationto2030intheSTEPSisfarbelowthelevelneededtolimitwarmingto1.5°C,highlightingtheurgentneedforfurthermeasurestoachievethegoalsoftheNZEScenario.Figure1.34⊳IncreaseinsolarPVandwindpowercapacitybetween2022and2030infiveeditionsoftheWorldEnergyOutlookSTEPSNZEScenario7ThousandGW654321WEO-2019WEO-2020WEO-2021WEO-2022WEO-2023WEO-2021WEO-2023IEA.CCBY4.0.WindandsolarPVprojectionsratchetedupaspolicysupportincreased,costsfellandmanufacturingexpanded,yetmoreisneededtogetontrackfornetzeroemissionsNote:WEO-2019dataisfortheNewPoliciesScenario,theclosestequivalenttotheStatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS).IEA.CCBY4.0.76InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20231.10.2NaturalgasTheSTEPSscenariosthatweremodelleduntiltheWEO-2021projectedstrongcontinuedincreasesinnaturalgasconsumption(Figure1.35).Upwardrevisionstorenewables1graduallynarrowedthespacefornaturalgastocontributetoelectricitydemandgrowth,resultingindownwardrevisionstodemandlevels,butthelong-termpicturestillsupportedcontinuedgrowthto2040andbeyond.Figure1.35⊳NaturalgasdemandprojectionsintheSTEPSto2040infiveeditionsoftheWorldEnergyOutlookbcm5500WEO-20195000WEO-2020WEO-20214500WEO-20224000WEO-2023350030002020203020402010IEA.CCBY4.0.Upwardrevisionstorenewableshavechippedawayatlong-termnaturalgasprojections,butthesharpestreductioncamein2022followingtheglobalenergycrisisNote:WEO-2019dataisfortheNewPoliciesScenario,theclosestequivalenttotheStatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS).Theeventsof2022–especiallytheRussianinvasionofUkraine–ledtoamajorrevisionintheoutlookfornaturalgas.TherewasanimmediatecutinexportstoEurope,andconfidencearoundtheworldwasshakenintheabilityofnaturalgastoactasareliableandaffordablefuel.Asaresult,naturalgasdemandin2040wascutbyaround570bcm(12%reduction)intheSTEPSpublishedintheWEO-2022.Aroundhalfofthisreductionwasduetoafastermoveawayfromgasinadvancedeconomies;theotherhalfwastheresultofmuchslowerprojectedgrowthinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Naturalgasdemandin2040hasbeenadjusteddownbyafurther140bcmintheSTEPSinthisOutlook.Thismainlyreflectstheupwardrevisiontotheoutlookforrenewables.Advancedeconomies,ledbyEurope,accountforaroundthree-quartersoftheoveralldownwardrevisioninnaturalgasdemand.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter1Overviewandkeyfindings77DemandforLNGin2050inthisOutlookisnearly15%lowerthanprojectedintheSTEPSoftheWEO-2021.Thisisasmallerreductionthanthenear20%downwardrevisioninoverallnaturalgasdemandbetweentheWEO-2021andthisOutlook.ButthelargeincreaseinnewliquefactionprojectsapprovedfordevelopmentintheinterveningyearsmeansthatplannedcapacityisnowsufficienttomeetLNGdemandintheSTEPSto2040,whichistenyearslaterthanprojectedintheWEO-2021.Thisopenstheprospectofloosermarketfundamentals,lowerpricesandaneasingofgassupplysecurityconcernsfromthesecond-halfof2030s,withpotentialupsidefordemandifthesedevelopmentsbuttressconfidenceingasamongprice-sensitiveemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.However,italsoraisesquestionsaboutthelong-termprofitabilityofprojects.IEA.CCBY4.0.78InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter2SettingthesceneContextandscenariodesignSUMMARY•ThereisanewcontextforthisWorldEnergyOutlook.Amorecomplexandfragmentedgeopoliticallandscapehasenergyasoneofitsdividinglines.Partlyasaresult,newenergyandindustrialpolicysettingsareemergingascountriescompeteforfootholdsinthenewcleanenergyeconomy,amidconcernsaboutenergysecurityandresilience.Greenhousegasemissionsremainatrecordlevelsandtheaccumulationofemissionsisheighteningphysicalclimaterisks.Andthisisalltakingplaceinadifficultmacroeconomiccontext,withtherecentcrisispushingupthecostoflivingandendingaperiodoflowinterestrates.•Someofthetensionsinenergymarketshaverecededin2023afteraperiodofextendedandextremeturbulencesince2020.However,numerousrisksremainandthecurrentrelativecalmmaynotlast.ContinuedfightinginUkraine,morethanayearafterRussia’sinvasion,isnowaccompaniedbytheriskofprotractedconflictintheMiddleEast.Periodsofextremeweatherarebecomingamajorhazardforenergysecurity.•Despiteheadwinds,therearestrongsignsofanaccelerationincleanenergytransitions.ThedeploymenttrendsforsolarPV,electricvehicles,batteriesandheatpumpsareencouragingandtheoverallbalanceofinvestmentisshiftingtowardscleanenergy.ForeveryUSD1spentonfossilfuels,USD1.8isnowspentonarangeofcleanenergytechnologiesandrelatedinfrastructure:fiveyearsagothisratiowas1:1.TheincreaseinspendingisconcentratedinadvancedeconomiesandChina.Amuchbroaderflowofcleanenergyprojects–basedonstrongernationalpoliciesandinternationalfinancialsupport–isessentialtomeettheSustainableDevelopmentGoals,includingenergyaccess,andglobalclimateandenergysecurityobjectives.•ThisOutlookexploresthreescenarios–fullyupdated–thatprovideaframeworkforexploringtheimplicationsofvariouspolicychoices,investmentandtechnologytrends.TheStatedPoliciesScenarioisbasedoncurrentpolicysettingsandalsoconsiderstheimplicationsofindustrialpoliciesthatsupportcleanenergysupplychainsaswellasmeasuresrelatedtoenergyandclimate.TheAnnouncedPledgesScenariogivesgovernmentsthebenefitofthedoubtandexploreswhatthefullandtimelyimplementationofnationalenergyandclimategoals,includingnetzeroemissionstargets,wouldmeanfortheenergysector.TheNetZeroEmissionsby2050Scenariomapsoutatransitionpathwaythatwouldlimitglobalwarmingto1.5°C.•Theglobaleconomyisassumedtoincreaseatanaverageof2.6%peryearto2050inthethreescenarios,whiletheglobalpopulationexpandsfrom8billiontodayto9.7billionin2050.Energy,carbonandmineralpricesfinddifferentequilibriumlevelsacrossthescenarios,butthepotentialforvolatilityremainshigh.Chapter2Settingthescene79UnitedStatesEuropeanUnionChinaRestofworld1000billionUSDInvestmentlowsThepatternofinvestmentsinrecentyearshasstartedtoshifttheworldtowardsamoreWorld(billionUSD)electriied,renewables-richenergysystem679Oilissionspower660Low-em433Naturalgas362493271Energyeiciency326Electricitygridsandbatterystorage391209Coal3523682015329179Electriication14717Low-emissionsfuels2022EconomicandpopulationEconomicandpopulationdriversgrowtharetwokeyunderlyingforcesfortheIndiaIndex(2022=1)AfricaSoutheastAsiaoutlook:theglobalGDPeconomyisassumedtoincreaseatanaverageofPopulation2.6%peryearto2050,whiletheglobal199020222050populationexpandsfrom8billiontodayto9.7LatinAmericaWorldUnitedStatesbillionin2050.MiddleEastEuropeanUnionJapanandKoreaChinaEurasia2.1NewcontextfortheWorldEnergyOutlookTheenergysectorhasbeenshakeninrecentyears,firstbytheCovid-19pandemicandthenbytheglobalenergycrisissparkedbyRussia’sinvasionofUkraine.Bothwerehugelydisruptive.Bothhadimpactsonenergymarketsthatleftmanyenergyproducersandconsumersfeelingbruisedbyvolatilefuelandelectricityprices.2Theseimpactspromptedarangeofreactionsfrompolicymakerstotryandlessentheimmediateimpactsandaddressfuturevulnerabilities,includingriskstoenergysecurityandaffordability,whileatthesametimefacinguptotheimperativetotransitiontocleanenergytechnologies.WhethertheseresponsesareadequatetothescaleofthechallengeisthecentralquestionofthisOutlook.Whenfuturegenerationslookback,willtheextendedcrisisof2020-2023beseenasthemomentwhentheworldtookdecisivestepstoaddressthemultiplerisksfacingtheenergysector,orwillthereactiontoitbeseenasanothermissedopportunity?Somekeytrendsin2023underscorethepersistenceofthestatusquo.Bymid-year,manyindicatorsoffossilfueldemandwerereturningtowheretheyhadbeenpriortothepandemic.Naturalgasdemandreboundedto2019levelsin2021,andisnowholdingsteadyafteratumultuous2022.Globaldemandforalloilproductstookalittlelongertocomeback,buthasalsonowreturnedto2019levels,withaviationfuelsthelasttobounceback.Andcoaldemanddippedduringthepandemicbutthenreachedanewrecordlevelin2022.Figure2.1⊳Pricesforoil,naturalgasandcoal,January2019toSeptember2023Oil(USD/barrel)Naturalgas(USD/MBtu)Coal(USD/t)160804001206030080402004020100JanSeptJanSeptJanSept201920232019202320192023JapanBrentEuropeUnitedStatesEuropeIEA.CCBY4.0.Fossilfuelpricesspikedin2022,beforemoderatingbacktowardspre-crisislevelsinrecentmonthsIEA.CCBY4.0.Notes:MBtu=millionBritishthermalunits;USD/t=USdollarspertonne.Europenaturalgasprice=naturalgasTTFindex;USnaturalgasprice=naturalgasHenryHubindex;Europecoalprice=northwestEuropeCIFARA;Japancoalprice=JapanCIFmarker.Nominalprices.Sources:USEIA(2023);Argus(2023);McCloskey(2023).Chapter2Settingthescene81IEA.CCBY4.0.Followingaperiodofextremevolatility,fossilfuelpricesmoderatedinthefirsthalfof2023althoughmarketbalancesremainfragile(Figure2.1).CrudeoilpricesreturnedaboveUSD90/barrelinSeptember2023,asmajorproducersintheOrganizationofthePetroleumExportingCountries-plus(OPEC+)groupingenactedcutstotheirproduction.Aftertheextraordinarypricespikesof2022thatsawnaturalgasregularlytradinginEuropeatpricesaboveUSD50permillionBritishthermalunits(MBtu)–theequivalentofmorethanUSD250/barrelofoil–EuropeanpricessettledbackataroundUSD10/MBtu,thoughthesepriceswerestillhighcomparedwiththoseseenoverthepastdecade.AfterrecordhighpricesofoverUSD400/tonneayearearlier,steamcoalpriceswerebackdownbelowUSD150/tonne.Doesthismeanthattheperiodofcrisisisbehindus?Andthattheenergysectorhasrevertedtothesamepathwaythatitwasonbefore?Neitherofthesepropositionsappeartobetrue.Russia'songoingwarinUkraineandinstabilityintheMiddleEastmeanahighriskoffurtherdisruptionandupheaval.Andtheenergypathwaynowlooksdifferent.Thereareunmistakeablesignsinmanypartsoftheworldofamajoraccelerationinthepaceofenergytransitions,evenifmacroeconomicconditionshavebecomemorechallenging.Thesevariouschanges,andthereactionstothem,meanthatthereisanewcontextforthisWorldEnergyOutlook:Thefuturewilltakeshapewithinamorefragmentedgeopoliticalandsecuritycontext.Russia’sinvasionofUkrainehaswidenedfracturesinthelandscapeofinternationalrelations,andenergyisoneofthedividinglines.WithflowsofRussianenergytoEuropenowatverylowlevels,oneofthemaintraditionalcorridorsforinternationalenergytradehasbeenclosed,leadingtoawholesalerealignmentinthewaythatfuelsmovearoundtheworld.Inamorefracturedgeopoliticalenvironment,policymakerstendtoviewmanyenergydevelopmentsthroughanenergysecuritylens.Thisdoesnotdisadvantagecleantechnologies;inmanycasestheyprovidesolutionstoenergysecurityconcerns.Butitputsapremiumonorderlyandsecurechangeandithasalsomeantthat,aspolicymakerslookbeyondtheimmediatenaturalgascrisis,attentionhasfocusedondependenciesincleanenergysupplychains,whichexhibitsignificantlyhigherlevelsofconcentrationinmanycasesthansuppliesofoilandnaturalgas.Governmentresponsestotheenergycrisisaresettohavelong-termimplicationsforenergyandindustrialpolicy.Insomecases,responseshaveincludedeffortstodevelopfossilfuelresources.Butingeneraltheemphasishasbeenonmeasurestofast-trackthedeploymentofcleanenergy,aswiththeInflationReductionActintheUnitedStates,moreambitiousnear-termtargetsandsupportmeasuresinEurope,andstrongsupportforcleanenergyinChina,IndiaandBrazil,amongothers.Aworldofmorepronouncedinternationalrivalrieshasalsoproducedarenewedfocusonindustrialstrategies.Thesetypicallyseektopromoteinvestmentindomesticproductionand/orsupplyfromfavouredjurisdictionsasawaytoincreasetheresilienceofsupplychainsandtobenefitfromnewjobsandeconomicopportunities.Cleanenergyhasbeenamajorfocusfor82InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023theseindustrialstrategiesascountriescompeteforfootholdsinthenewcleanenergyeconomy.ThesevariousstrategiesareintegratedintoourWorldEnergyOutlook-2023(WEO)scenariodesign.Emissionscontinuetoaccumulateintheatmospherewithallthatthisimpliesforclimate-relatedrisks.Betweenthebeginningof2019andtheendof2022,theglobal2energysystemwasresponsibleformorethan140gigatonnesofcarbondioxide(GtCO2)emissions(Figure2.2).Thismeansthattheworldisracingthroughtheavailablebudgetthatiscompatiblewithlimitingtheriseinglobalaveragetemperaturesto1.5degreeCelsius(°C).Theseadditionalemissionsarecontributingtomorefrequentheatwaves,droughtsandotherextremeweathereventsthataddtothepressureonvulnerablepopulationsandenergysystems.Figure2.2⊳AnnualchangeinglobalCO2emissionsfromenergycombustionandindustrialprocesses,1990-20224030GtCO₂201019902000201020222GtCO₂1IEA.CCBY4.0.0-1-2Energy-relatedCO2emissionsrose1%in2022,andareexpectedtorisebyasimilaramountin2023Note:GtCO2=gigatonnesofcarbondioxide.IEA.CCBY4.0.Themacroeconomicbackgroundhasbecomemoredifficultwithinflationarypressuresin2022markingtheendofaneraofverycheapcapitalandlowinterestrates.Manyemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesareparticularlydisadvantagedbyhigherborrowingcostsandrisingfiscalpressures.AccordingtotheWorldBank,incomespercapitain2024willremainbelow2019levelsinmorethanone-thirdoflowincomecountries(WorldBank,2023a).Higherborrowingcostsriskputtingsomecleanenergyprojectsatadisadvantagerelativetotraditionalenergyinvestmentsbecausethelatterhavelowerupfrontcosts,eventhoughthecleanenergyprojectsmaybemorecosteffectiveovertimesincetheydonotdependonfossilfuelinputs.Chapter2Settingthescene832.1.1NewcleanenergyeconomyTheenergycrisishasbroughtforwardtheemergenceofanewcleanenergyeconomy.Marketturbulencepromptedashort-termscrambleforalternativefossilfuelsupplies,particularlyafterRussiacutnaturalgasdeliveriestoEurope,butitalsosignificantlyincreasedcapitalflowsandassociatedinvestmentsthatsupportstructuraltransformationoftheenergysystem.Priortothepandemic,annualinvestmentinenergysystemswasjustoverUSD2trillion,splitroughlyinequalpartsbetweenfossilfuelsandcleanenergy(thelatterincludesrenewables,otherlow-emissionssourcesofgenerationandfuels,andspendingonefficiencyimprovements,end-useelectrification,gridsandstorage).TheIEAestimatefor2023isthataroundUSD2.8trillionissettobeinvestedintheenergysector(IEA,2023a).Fossilfuelspendinghasbeenrisingslowlyafterasharpdropin2020butremainsroughlywhereitwasfiveyearsago,soalloftheincreasehascomefromcleanenergy(Figure2.3).Thetrendsarefarfromuniformacrosstechnologies,butgrowthinsomekeycleanenergytechnologyareas,notablysolarphotovoltaics(PV),isnowalignedwiththenear-termrequirementsoftheIEANetZeroEmissionsby2050(NZE)Scenario,whichlimitsglobalwarmingto1.5°C.Theemergenceofthenewcleanenergyeconomyisstartingtochangethefaceoftheenergysystem.OuranalysisintheWorldEnergyOutlook-2022highlightedthatthepolicyandmarkettrendsreflectedintheStatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS),werealreadystrongenoughtodeliverapeakinglobalfossilfueldemandbytheendofthe2020s.UpdatedprojectionsinthisWorldEnergyOutlook-2023underscorethisconclusionandbringinnewpointsofreferencetosupportit.Figure2.3⊳GlobalenergyinvestmentincleanenergyandfossilfuelsBillionUSD(2022)2000Cleanenergy1600Fossilfuels1200800400201520162017201820192020202120222023eIEA.CCBY4.0.IEA.CCBY4.0.ForeveryUSD1spentonfossilfuels,USD1.8isnowbeingspentoncleanenergy;fiveyearsagothisratiowas1:1Notes:2023e=estimatedvaluesfor2023.Numbersareinreal2022USdollars.84InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Themostdynamicareascanbegroupedundertheheadingofcleanelectrification.Thisisunderpinnedbyinvestmentinlow-emissionstechnologies:annualglobalrenewableelectricitycapacityadditionsaresettorisetomorethan500gigawatts(GW)in2023,thelargestabsoluteincreaseeverseen.Theshareoflow-emissionsgenerationsources(renewablesplusnuclear)intheglobalmixissettoreach40%in2023–anewhigh.Solarisleadingthecharge:solarPVcapacity,includingbothlargeutility-scaleandsmall2distributedsystems,accountsfortwo-thirdsofthe2023estimatedincreaseinglobalrenewablecapacity.The26%annualgrowthinsolargenerationin2022wasalignedwiththenear-termratesrequiredintheNZEScenario,andplannedadditionsprovideconfidencethathighgrowthcanbesustained.Nuclearcapacityadditionsgrewby40%in2022,with8GWcomingonline,mostlyinChina,Finland,KoreaandPakistan.Moreover,manygovernmentsaretakingafreshlookathownuclearmightcontributetotheirenergyfutures,astheydidaftertheoilpriceshocksofthe1970s.Electricityisexpandingtonewend-usesatscale,notablytoprovidemobilityandheat.Globalelectricvehicle(EV)salesjumpedbymorethan50%in2022,reachingarecordhighofmorethan10million.Deploymentofutility-scaleandbehind-the-meterbatterystoragegrewby90%in2022,whileheatpumpsalsosawarecordyearwithsalesup11%,almostdoubletheleveloffiveyearsago.Cleanelectrificationisbeingcomplementedbyarenewedfocusonefficiency.Countriesrepresentingmorethan70%ofglobalenergyconsumptionhaveintroducedneworstrengthenedefficiencypoliciessincethestartoftheenergycrisis.TheEuropeanUnionagreedonstrongerrulesinMarch2023whichnearlydoubletherateofannualsavingsthatEUmembercountriesneedtodeliverbetween2024and2030;theUnitedStatesraisedthelevelofsupportofferedtohouseholdsforefficiencyupgrades;Chinasteppedupitspushtoincreaseindustrialenergyefficiency;andIndiapassednewefficiencylawsthatreinforcebuildingenergycodesandappliancestandards,whilealsopromotingsustainablechoicesviaitsLifestyleforEnvironmentInitiativedomesticallyandattheGroupof20(G20).IEA.CCBY4.0.Progressisadvancingmostrapidlyinareaswheretechnologiesarealreadymatureandcostcompetitive,suchaselectricitygenerationandpassengertransport.Butafullcleanenergytransitionwillrequireprogressinallareas,includingthosewhereemissionsarehardertoaddress.Thisnecessitatespolicysupportforinnovationandearlydeployment.Newinitiativesandprogrammesarenowinplaceforfuelssuchaslow-emissionshydrogenandtechnologiessuchascarboncapture,utilisationandstorage(CCUS).Investmentintheseareasisrisingfromalowbaseandonlyahandfulofprojectshaveyetmadeitovertheline:only4%ofannouncedprojectsforlow-emissionshydrogenhavetakenafinalinvestmentdecision.However,policymakersarenowlookingatwaystoprovidegreatercertaintyondemand,increaseclarityoncertificationandregulation,andstimulatenewinfrastructuretoallowmoreprojectstoprogresstotheimplementationphase.Chapter2Settingthescene85IEA.CCBY4.0.AnalysispreparedbytheIEAforthe2023GroupofSeven(G7)LeadersSummitinHiroshima,Japan,highlightedtheimpressivegrowthinmanufacturingcapacityannouncementsinrecentmonths(IEA,2023b).Ifallannouncedprojectsweretocometofruition,solarPVmanufacturingcapacitywouldcomfortablyexceedthedeploymentneedsoftheNZEScenarioin2030.Moreover,iftheyallproceed,announcedprojectsforEVbatterymanufacturingcapacitycouldcovervirtuallyallofthe2030globaldeploymentneedsidentifiedintheNZEScenario.TheworldisstillalongwayfromatrajectoryforemissionsthatisconsistentwiththeParisAgreementandthe1.5°Ctarget,butthepaceofchangeinsomekeyareasisimpressive.2.1.2Uneasybalanceforoil,naturalgasandcoalmarketsOilmarketsfacedtwomajorshort-termuncertaintiesatthestartof2023:thestrengthoftherecoveryindemandinChinaastheeconomyemergedfromtheCovid-19lockdowns,andtheimpactonenergysupplyfromRussiaduetothepricecapimposedbyaG7-ledcoalitiononRussianexportsofcrudeoilandrefinedproducts.Asofmid-year2023,therecoveryofdemandinChinahasbeenquitestrong.Despiteslowingofitseconomicrecovery,Chinaisexpectedtoaccountforwelloverhalfofglobaloildemandgrowthin2023.AndRussianproductionandexportscontinuetofindbuyersaroundtheworld,althoughitsrevenueshavebeenconsiderablylowerthanayearearlier.Growthinoildemandisbeingdrivenbyahandfulofsegments,notablyaviationfuels.ConcernsaboutweakerdemandandpriceshavepromptedaseriesofoutputcutsfromSaudiArabiaandothermembersoftheOPEC+grouping.Naturalgasmarketshavemovedtowardsagradualrebalancingaftertheshocksofrecentyears.HighinventorylevelsatstoragesitesinkeyAsianandEuropeanmarketsprovidegroundsforcautiousoptimismaheadofthe2023-2024winterheatingseasoninthenorthernhemispherethatmarketswillbecalmerthaninrecentyears,butmajoruncertaintiesremain.RelativelymildweatherandrestraineddemandfromChinalessenedthedisruptiveimpactofRussiancutstoitsEuropeandeliveriesin2021-2022,anditcannotbetakenforgrantedthatthiswillbethecaseinthecomingwinter.Marketsremainvulnerabletounexpectedoutagesordisruptions,especiallyforcountriesdependentonspotmarketsforsupply.Aswithoil,patternsofnaturalgastradehavechangeddramaticallyasaresultoftheglobalgascrisis.Astrikingindicatorofareshapedglobalgasmarketisthatliquefiednaturalgas(LNG)hasnowbecomeabasesourceofsupplyforEurope,withitsshareintotaldemandintheEuropeanUnionrisingfromanaverageof12%overthe2010stocloseto35%in2022,similartothecontributionfrompipedgasfromRussiabeforeitsinvasionofUkraine.Thishasknock-oneffectsonallaspectsofnaturalgasmarketsandonhowcountriescollaboratetoensuregassecurity.Anumberofnewliquefactionprojectshavereceivedthegreenlightsince2022,addingtothewaveofnewLNGsupplyscheduledtostartoperationinthesecondhalfofthisdecade.86InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Box2.1⊳HowdidtheEuropeanUnionmakeupforatripledeficitofnaturalgasin2022?AnalysisoftheglobalenergycrisistendstofocusonthecutsinRussiangasdeliveriestotheEuropeanUnionfrommid-2022asthetrigger.The80billioncubicmetre(bcm)dropinpipelinesuppliesfromRussiawasindeedaprimarycauseofmarketturbulence,both2inEuropeandfurtherafield.Butitwasnottheonlyone.ChangesinRussianbehaviouringasmarketsbeganwellbeforeitsinvasionofUkraine,andGazpromwasmuchslowerthanusualtorefillitsEuropeangasstorageinthethird-quarter2021.ThecallonthetightgasmarketwasexacerbatedevenfurtherbyaverypooryearforbothhydropowerandnuclearoutputinEuropein2022.Overall,thistripledeficitmeantthattherewasalmost160bcmof“missinggas”toreplacein2022(Figure2.4).Alternativesourcesofsupplymetover40%ofthedeficit,withLNGfromtheUnitedStatesmakingbyfarthelargestcontribution.Europe’sabilitytosourcesupplywasgreatlyfacilitatedbylowerdemandinChina,butnonethelesscausedsignificantpainforotherimport-dependenteconomiesthatfoundthemselvesoutcompetedforavailablesupply.However,themainadjustmentsweremadeonthedemandside.Gasuseinindustryfellbyalmost25%,overhalfofwhichwastheresultofcurtailmentinenergy-intensiveindustries(withfewsignsin2023ofameaningfulrecovery).Theoft-discussedmildwinteraccountedforsome10%oftheoveralldeficit,whichwasaroundthesameasthecombinedcontributionfromnewrenewablecapacityandefficiencyimprovements.Contrarytotheperceptionthatcoalplayedasignificantrole,additionalcoalconsumptionfilledlessthan4%ofthegap.Figure2.4⊳FactorsstrainingthenaturalgasbalanceandaccommodatingmeasuresintheEuropeanUnionin2022bcm160SupplyresponseLowerhydroOtherandnuclearSupplyDemandAdditionalNorwaypiperesponseresponseAdditionalotherLNG120AdditionalUSLNGAdditionalgasintostorageDemandresponseOther80AdditionalcoaluseLowerelectricitydemand40LowerRussianEnd-useefficiencypipelinegasFuelswitchingIndustrygascurtailmentAdditionalneedMildwinterforgasBehaviouralchangeAdditionalrenewablesIEA.CCBY4.0.CutsinRussiandeliveriesputhugestrainsontheEUgasbalancein2022,butitwasnottheonlyfactorinplaygivenlowstoragelevelsandapooryearforhydroandnuclearIEA.CCBY4.0.Notes:bcm=billioncubicmetres;LNG=liquefiednaturalgas.Chapter2Settingthescene87IEA.CCBY4.0.Oilandgasinvestmenthasbeenaffectedbyuncertaintiesconcerningfuturedemand.Itisstrikingthat,despiterecordrevenuesin2022,spendingonoilandgasproductionisoneofthefewinvestmentindicatorsthatremainsbelowpre-crisislevels(coalsupplyinvestments,forexample,arehigherthantheywerein2019).Intermsofourscenarios,currentoilandgasspendingisbroadlyalignedwiththelevelsrequiredintheSTEPSin2030,butwellabovethelevelsrequiredtomeetmuchlowerdemandintheNZEScenario.Coaldemandhasbeenonanelevatedplateauandreachedarecordlevelin2022ashigherdemandinIndia,ChinaandSoutheastAsiamorethanoffsetdeclinesintheUnitedStates.InEurope,coalconsumptionincreasedby2%duringtheenergycrisis,withlowerindustrialconsumptionbalancingoutgrowthincoaluseforpowergeneration.Earlysignsin2023suggestcontinuedincreasesincoalconsumptioninmanypartsofAsia,accompaniedbysignificantfallsindemandinNorthAmericaandalsoinEuropeasthelatterresumespre-crisistrends.Increasesincoalconsumptionarebeingaccompaniedbyincreasesincoalproductioninthethreelargestcoalproducers–China,IndiaandIndonesia–withbothChinaandIndiareachingnewmonthlyproductionhighsinMarch2023.2.1.3KeychallengesforsecureandjustcleanenergytransitionsEvenascleanenergytransitionsgatherpace,IEAanalysishashighlightedfourkeyareasthatrequireurgentattentioniftheworldistoseeorderlybutrapidchange.ThesearerecurringthemesinthisOutlook.FirstisacrucialconcernthatadisproportionatelylowshareofcleanenergyinvestmentisgoingtoemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChina.Withafewexceptions,suchasinvestmentinsolarPVinIndia,thelevelofspendingoncleanenergyinthesecountriesinrecentyears,atlessthanUSD250billionperyear,isfaroutoflinewithwhatisrequiredtomeetrisingenergyneedsinasustainableway.Asthingsstand,countriesaccountingfornearlytwo-thirdsoftheworld’spopulationaccountforonly15%ofglobalcleanenergyinvestment(Figure2.5).Bringingdownthecostofcapitalbytacklingahostofrealandperceivedrisksassociatedwiththeseinvestmentsandincreasingtheavailabilityofcapital,bothdomesticandinternational,isanessentialsteptowardsimprovingthesituation.ExpansionofcleanenergyinvestmentisapreconditionnotonlytoachieveuniversalaccesstomodernenergybutalsotodeliveronotherUnitedNationsSustainableDevelopmentGoalsinareasasdiverseaspovertyreduction,healthandeducation.Exposuretovolatileenergypricesinmanydevelopingeconomieshasbeenaccompaniedbymajorconcernsaboutfoodsecuritycausedinpartbyhighfuelandfertiliserprices,andhigherdebtburdensandfiscalpressures.Thedrivetoprovideuniversalaccesstomodernenergyhasslowedinrecentyearsandevenreversedinsomeplaces:775millionpeoplestilllackaccesstoelectricityworldwideand2.2billionpeoplelackaccesstocleancookingfuels.ThisOutlookmarksthemid-pointoftheimplementationoftheUN2030AgendaforSustainableDevelopment,adoptedin2015.Inmostcases,theworldiswellshortofhalfwaytoreachingits2030goals.88InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Figure2.5⊳Shareoftotalpopulationandcleanenergyinvestmentbyregion,2022PopulationCleanenergyinvestment70%60%250%40%30%20%10%AdvancedChinaOtherAdvancedChinaOthereconomiesEMDEeconomiesEMDEIEA.CCBY4.0.Mostpeopleliveinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,butonlyafractionofcleanenergyinvestmentistakingplaceinthosecountriesNote:OtherEMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesexceptChina.IEA.CCBY4.0.Secondisthechallengeofunevenprogressbeingmadeacrossdifferentareasoftechnologyandinfrastructure.DeploymenttrendsforsometechnologiesaresufficientlyfasttobealignedwiththeIEANZEScenario,butthetrendsformostarenot.Ofthe50technologiesandcross-cuttingareasassessedaspartoftheIEATrackingCleanEnergyProgress,onlythreewereevaluatedasfullyontrack:solarPV,EVsandefficientlighting(IEA,2023c).Mostrequireadditionaleffortstogetontrack:theseincludewindpower,gridsandstorage,electrolysers,efficiency,innovationanddigitalisation.Andsomearedefinitivelyofftrack,includingthoseneededforlong-distancetransportationbytruck,airandshipandthoseneededbymanylargeindustrialsub-sectors.Reachingnetzeroemissionswillclearlyrequireprogressacrosstheboard,andtherearemultiplecommercial,technical,policyandsupplychainissuestoresolve.Theriskwithanunevenpaceofprogressisthatslowermovingelementsmaydeterminetheoverallpaceofchange.Gridavailability,whichisalreadyhinderinggrowthinrenewables-basedgenerationinsomemarkets,isacaseinpoint.Atleast3000GWofrenewablepowerprojects,ofwhich1500GWareinadvancedstages,arewaitingingridconnectionqueues–equivalenttofivetimestheamountofsolarPVandwindcapacityaddedin2022(IEA,2023d).Maintainingrapidratesofrenewablesdeploymentrequiresbroadlymatchedprogressacrossalltheinterlinkedpartsoftheenergysystem,includinggrids,storageanddispatchablelow-emissionssourcesofgeneration.Withoutsuchprogress,theflexibleandsecureoperationofpowersystemsasawholeinevitablywillbeimpaired.ComplementarymeasurescanalsoChapter2Settingthescene89playanimportantparttofacilitaterapidincreasesinlow-emissionspower.Forexample,improvementsinenergyefficiency,particularlyforrapidlyincreasingdemandareassuchasspacecooling,canalleviatestrainsonsystemsandobviatetheneedforexpensivesupply-sideinvestmenttomeetpeakdemandlevels,whilereformstoelectricitymarketstructuresandpricingcanhelpconsumerstobenefitfromtheloweroperationalcostsofrenewables.Athirdkeyareaistomitigatenewenergysecurityvulnerabilitiesinarapidlychangingenergysystem.Traditionalconcernsaboutfuelsecuritydonotdisappearinenergytransitions,andrapiddeploymentofcleanenergytechnologiesrequiresresiliencealonganewsetofsupplychains.Forexample,themanufacturingprocessforEVsdependsonsteel(whichinthefuturewillberequiredtobenearzeroemissionssteel)andothermaterials,andultimatelyonthemineralsandoresneededtoproducethem,plusanodesandcathodesforbatterysupply.Eachstepoftheprocesshasdifferentleadtimesandinvolvesspecificchallenges.Cleanenergysupplychainstodayarehighlyconcentrated.Chinahasanoutsizedpresence.IthashugesharesofglobalmanufacturingcapacityforsolarPVmodulesandbatteries(75%)aswellasaverystrongpositionintherefiningandprocessingofcriticalminerals.Inthelastyear,majorpolicyannouncementsindicatedevelopmentsthatwilldiversifysomesupplychains,asevidencedbythescale-upinplannedbatterymanufacturingcapacityintheUnitedStatesfollowingtheadoptionoftheInflationReductionAct.Yet,levelsofsupplychainconcentrationlooklikelytoremainhigh.Thismakestheentiresystemvulnerabletounforeseenchangesthatcouldariseduetoshiftsinnationalpolicies,commercialstrategies,technicalfailuresornaturalhazards.Afourthkeyareaistheneedtoensurepeople-centredtransitions.Inclusiveapproachesareessentialtoensurethatthebenefitsofcleanenergytransitionsarefeltwidelyacrosssocieties,andtomaintaintheirpoliticalacceptability.Theturbulenteventsofrecentyearsclearlypointtotherisksandcoststhatariseiftheprocessofchangeisdisorderlyordisjointed,orifvulnerablegroupswithinsocietiesareleftbehind.Duringtheglobalenergycrisisin2022,governmentsallocatedanextraUSD900billiontoshieldconsumersfromtheimpactofspirallingenergyprices,aroundaquarterofwhichwasspecificallydirectedtolowincomehouseholdsandthehardesthitindustries.Furthermeasureswillbeneededtoenabletheleastwell-offtoinvestincleanandmoreefficientenergytechnologiesforhouseholduse,especiallywherethesetechnologiesentailhigherinitialcapitaloutlaythanfossilfuelequivalents,eventhoughtheyofferloweroperatingcosts.IEA.CCBY4.0.2.2WEOscenariosThisOutlookemploysthreemainscenariostoexploredifferentpathwaysfortheenergysectorto2050.Eachscenarioisfullyupdatedtoincludethemostrecentavailableenergymarketandcostdata.Eachscenariorespondsindifferentwaystothefundamentaleconomicanddemographicdriversofrisingdemandforenergyservices.Thesedifferenceslargely90InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023reflectthevariouspolicychoicesassumedtobemadebygovernments,which,inturn,shapeinvestmentdecisionsandthewaysinwhichhouseholdsandcompaniessatisfytheirenergyneeds.TheprojectionsarederivedfromtheGlobalEnergyandClimate(GEC)Model,whichisalarge-scalemodellingframeworkdevelopedattheInternationalEnergyAgency(IEA).The2modelmatchesenergydemandandsupplyacrossmultiplecountriesandregions,takingaccountofaverywiderangeoffuelsandenergytechnologies,includingnotonlythosethatarewidelyavailabletoday,butalsothosethatarejudgedtobeapproachingcommercialisation.TheGECModelisasimulationmodelthatreflectsthereal‐worldinterplaybetweenpolicies,costsandinvestmentchoicesandwhichprovidesinsightsintohowchangesinoneareamayaffectothers.NoneofthescenariosincludedinthisOutlookshouldbeconsideredaforecast.Theintentionisnottoguidethereadertowardsasingleviewofthefuture,butrathertopromoteadeeperunderstandingofthewaythatvariousleversproducediverseoutcomes,andtheimplicationsofdifferentcoursesofactionforthesecurityandsustainabilityoftheenergysystem.AnimportantelementofthisOutlookisthatallscenariosnowtakeintoaccountnotonlyenergyandclimate-relatedpoliciesbutalsoindustrialstrategiesthataffecttherateatwhichdifferenttechnologiesmightenterthemix.Thismeansthatthescaleandlocationofmanufacturingcapacityforvariouscomponentsofthecleanenergysystemhavebecomeimportantvariablesinscenarioconstructionanddesign.Thescenariosare:NetZeroEmissionsby2050(NZE)Scenario:Thisnormativescenarioportraysapathwayfortheenergysectortohelplimittheglobaltemperatureriseto1.5°Cabovepre‐industriallevelsin2100(withatleasta50%probability)withlimitedovershoot.TheNZEScenariohasbeenfullyupdatedandisthefocusoftherecentlyreleasedNetZeroRoadmap:AGlobalPathwaytoKeepthe1.5°CGoalinReach(IEA,2023d).TheNZEScenarioalsomeetsthekeyenergy‐relatedUNSustainableDevelopmentGoals(SDGs):universalaccesstoreliablemodernenergyservicesisreachedby2030,andmajorimprovementsinairqualityaresecured.EachpassingyearofhighemissionsandlimitedprogresstowardstheSDGsmakesachievingthegoalsoftheNZEScenariomoredifficultbut,basedonouranalysis,therecentaccelerationincleanenergytransitionsmeansthatthereisstillapathwayopentoachievingitsgoals.IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnouncedPledgesScenario(APS):Thisscenarioassumesthatgovernmentswillmeet,infullandontime,alloftheclimate‐relatedcommitmentsthattheyhaveannounced,includinglongertermnetzeroemissionstargetsandpledgesinNationallyDeterminedContributions(NDCs),aswellascommitmentsinrelatedareassuchasenergyaccess.Pledgesmadebybusinessesandotherstakeholdersarealsotakenintoaccountwheretheyaddtotheambitionsetoutbygovernments.Sincemostgovernmentsarestillveryfarfromhavingpoliciesannouncedorinplacetodeliverinfullontheircommitmentsandpledges,thisscenariocouldberegardedasgivingthemthebenefitofthedoubt,Chapter2Settingthescene91andveryconsiderableprogresswouldhavetobemadeforittobeachieved.Countrieswithoutambitiouslong-termpledgesareassumedtobenefitinthisscenariofromtheacceleratedcostreductionsthatitproducesforarangeofcleanenergytechnologies.TheAPSisassociatedwithatemperatureriseof1.7°Cin2100(witha50%probability).StatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS):Thisscenarioisdesignedtoprovideasenseoftheprevailingdirectionofenergysystemprogression,basedonadetailedreviewofthecurrentpolicylandscape.WhereastheAPSreflectswhatgovernmentssaytheywillachieve,theSTEPSlooksindetailatwhattheyareactuallydoingtoreachtheirtargetsandobjectivesacrosstheenergyeconomy.OutcomesintheSTEPSreflectadetailedsector-by-sectorreviewofthepoliciesandmeasuresthatareactuallyinplaceorthathavebeenannounced;aspirationalenergyorclimatetargetsarenotautomaticallyassumedtobemet.TheSTEPSisnowassociatedwithatemperatureriseof2.4°Cin2100(witha50%probability).IEA.CCBY4.0.2.2.1PoliciesEnergyandclimatepoliciesAcrucialpreparatorystepforeveryannualeditionofOutlookisthereviewandassessmentofnewpolicies,regulatorymeasures,targetsandannouncementsthatmightaffecttheevolutionoftheenergysystem.Therecentglobalenergycrisishasspurredawiderangeofenergyandclimatepolicyresponsesandinitiativesthatarenowincorporatedintothescenarios.TheUSInflationReductionActandothernotablenewpoliciesthatweretakenintoaccountintheWEO-2022remainimportantpointsofreference.Thereviewcoversalltypesofpoliciesthathaveabearingonenergysystems,includingdecisionstoproceedwithnewoilandgaslicensingrounds,methanereductionactionplans,andinitiativesandstrategiesforenergyaccess.TheinitialyearsofthescenarioprojectionsarealsoinformedbythedetaileddatabasesthattheIEAmaintainsforvarioustypesofannouncedorplannedenergyprojects.Forexample,overthelastyeartheEuropeanUnionsteppedupitsclimateambitionwithnewtargetsforrenewablesandenergyefficiency.ItreformedtheEUEmissionsTradingSystem(ETS)andestablishedanewETSforthebuildingsandroadtransportsectors.Further,itintroducedaCarbonBorderAdjustmentMechanism(CBAM)thatwilllevyapriceoncarbonembeddedinimportedproductsinselectedsectors,andalsoincreasedemissionsreductiontargetsforsectorsnotcoveredbyanETS.JapanestablishedaroadmapforitsGreenTransformation(GX)programmethataimstoraisetheshareofrenewablesandnuclearinpowergenerationandtoensurethatallnewprivatecarssoldarelow-emissionsvehiclesby2035.GXwillbesupportedbycarbonpricingandsovereignGXtransitionbonds.Canada,inits2023federalbudget,allocatedsignificantfundingtoacceleratethedeploymentofcleanenergytechnologiesandtodecarboniselargeemitters.Indonesia,VietNamandSenegalsignedJustEnergyTransitionPartnerships(JETP),inwhichtheycommittedtoacceleratethedecarbonisationoftheirrespectivepowersectors.SouthAfricaalsopublisheditsJETPinvestmentplans.92InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IndustrialpoliciesManycountriesareputtingspecificpoliciesinplacetoencouragecleanenergymanufacturing.Ourscenariosnowtakeaccountofthesepoliciesinassociationwithcosts,targetsandothervariablesformodellingandcalibratingdeploymenttrends.Chinahasaveryhighshareofcurrentmanufacturingcapacityacrossarangeoftechnologies.2FollowingtheadoptionoftheInflationReductionAct(IRA)in2022,theUnitedStateshasputinplacearangeoftaxcreditsandfederalsupportforinvestmentincleanenergymanufacturing,withafocusonrenewables,low-emissionshydrogen,CCUS,EVs,cleanenergymanufacturingandcriticalminerals.Canadahasalsoestablishedfundingandtaxcreditsupportmechanismsforcriticalminerals,cleanenergytechnologiesandcleanenergymanufacturing.TheEuropeanUnionadoptedaGreenDealIndustrialPlanthattargetsincreasedpublicandprivateinvestmentincleantechnologymanufacturing,andtheEuropeanCommissionproposedaCriticalRawMaterialsActwithbenchmarksfordomesticextraction,processingandrecycling.Othercountrieshavemovedinasimilardirection,withthenotableexampleofIndia’sproduction-linkedincentiveschemetoboostbatteryandsolarPVmanufacturingcapacity.IEA.CCBY4.0.2.2.2EconomicanddemographicassumptionsIneachofthethreescenarios,theglobaleconomyisassumedtogrowby2.6%peryearonaverageovertheperiodto2050.Thisisbroadlyinlinewithtrendgrowth,butvariesbycountryandbyregionandovertime,reflectinginvestmentdynamics,employmentratesandchangesintermsoftrade(Table2.1).Weholdtheassumedratesofeconomicgrowthconstantacrossscenariostoallowforacomparisonoftheeffectsofdifferentenergyandclimatechoicesagainstacommonbackdrop.However,werecognisethatthepace,designandchoiceofpolicyandregulatorymechanismsusedtodrivechangeintheenergysystemwillhavewidereconomicimpacts–bothpositiveandnegative–acrosscountriesandregions.TheinitialyearsintheOutlookareshapedbycountries’exposureandresiliencetoshocksandbywheretheyarecurrentlypositionedintheeconomiccycle.Thereverberationsfromthepandemicandtheglobalenergycrisisarebeingfeltacrossthebroadereconomyashouseholdpurchasingpoweriserodedbyhigherinflationandasbusinessinvestmentisrestrainedbyrisingborrowingcosts(althoughcleanenergyappears,insomecases,tobebuckingthistrend).Notwithstanding,labourmarketconditionsremainrelativelybuoyant:theunemploymentrateisatornearitslowestlevelinhalfacenturyinmostcountries,andthisishelpingtosupporthouseholdincomeandeconomicactivity.GlobalGDPgrowthovertheperiodto2030isprojectedtoaverage3%.Thenear-termeconomicoutlookspublishedbyinternationalorganisations,suchastheInternationalMonetaryFundandtheOrganisationforEconomicCo-operationandDevelopment,emphasisethesignificantuncertaintyandthedownsiderisksthatpervadeGDPgrowthandinflationprojections.OnekeyriskisthatinflationcouldbemorepersistentChapter2Settingthescene93thanexpected,promptingfurtherhikesininterestrateswithuncertainconsequencesinfinancialmarkets,notablyinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Table2.1⊳GDPaveragegrowthassumptionsbyregionCompoundaverageannualgrowthrateNorthAmerica2010-20222022-20302030-20502022-2050UnitedStates2.0%1.8%2.0%1.9%2.1%1.9%1.9%1.9%CentralandSouthAmerica1.2%2.3%2.4%2.4%Brazil0.9%1.8%2.3%2.1%1.7%1.8%1.4%1.5%Europe1.5%1.6%1.1%1.3%EuropeanUnion2.9%3.8%4.0%4.0%1.2%1.3%2.7%2.3%Africa2.5%3.0%3.1%3.0%SouthAfrica1.9%1.0%1.4%1.3%MiddleEast1.4%0.1%0.6%0.4%Eurasia4.8%4.1%2.9%3.3%6.5%3.9%2.4%2.8%Russia5.7%6.4%4.3%4.9%AsiaPacific0.6%0.7%0.5%0.6%4.3%4.6%3.3%3.7%ChinaIndiaJapanSoutheastAsiaWorld3.0%3.0%2.5%2.6%Note:CalculatedbasedonGDPexpressedinyear-2022USdollarsinpurchasingpowerparityterms.Source:IEAanalysisbasedonIMF(2023)andOxfordEconomics(2023).IEA.CCBY4.0.PopulationisamajordeterminantofmanyofthetrendsintheOutlook.WeusethemediumvariantoftheUnitedNationsWorldPopulationProspects,wheretheglobalpopulationisassumedtorisefrom8billionpeoplein2022to8.5billionin2030and9.7billionin2050.Populationgrowthinthemediumvariantisnotlinear,andtherateofgrowthslowsovertime.Demographictrendsdifferbycountryandregion.Ageingpopulationsandslowingfertilityratesmeanthesizeofthepopulationin2050isexpectedtobesmallerthantodayintheEuropeanUnion,Russia,JapanandChina.Incontrast,theUnitedNationsprojectsabillionmorepeopleinAfricaby2050,accountingforthree-fifthsoftheglobalpopulationincrease.India’spopulationhasnowovertakenthatofChinaandisprojectedtoreachalmost1.7billionby2050,some360millionpeoplemorethaninChina(UNDESA,2022).Inthepast,thedevelopmentofeconomieshastypicallybeenassociatedwiththemigrationofruralworkerstotownsandcitiesinsearchofbetterpayingjobs.Thispatternofdevelopmentisassumedtocontinueovertheperiodto2050.Infact,inmostregionsthe94InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023changeinthepopulationisentirelyconcentratedinurbanareas.OnlyAfricaisexpectedtoexperienceanincreaseinthesizeofitsruralpopulationbythemiddleofthecentury,andeventhereitisdwarfedbyamuchlargerincreaseintheurbanpopulation(Figure2.6).IntheAsiaPacificregion,morethan400millionpeoplemovefromruralareastotownsandcitiesby2050.Ifthemodelofurbandevelopmentremainsbroadlyasitisnow,thisglobalincreaseintheurbanpopulationwillhavemajorconsequencesfortheenergyoutlook,notleastby2increasingdemandforconstructionmaterials,suchassteelandconcrete.Figure2.6⊳Changeinpopulationinurbanandruralareasbyregionto2050Millionpeople1250Urban1000RuralTotalchange7505002500-250-500AfricaMiddleEurasiaAsiaNorthC&SEuropeEastPacificAmericaAmericaIEA.CCBY4.0.ExceptinAfrica,theincreaseinpopulationinthecomingdecadeswillbeentirelyconcentratedinurbanareasNote:C&SAmerica=CentralandSouthAmerica.Sources:UNDESA(2022);WorldBank(2023b);IEAdatabasesandanalysis.IEA.CCBY4.0.2.2.3Energy,criticalmineralandcarbonpricesOilpricesIneachofthethreescenarios,oilandnaturalgaspricesactasintermediariesbetweensupplyanddemandtoensurethatsourcesofsupplymeetchangesindemandandholdtheenergysysteminequilibrium(Table2.2).Thisbalancingactmeanspricesinourscenariosfollowrelativelysmoothtrajectories.Wedonottrytoanticipatethepricecyclesthatcharacterisecommoditymarketsinpractice,butwerecognisethatthepotentialforoilandgaspricevolatilityiseverpresent,especiallygiventheprofoundchangesthatareneededtomeettheworld’sclimategoals.IntheSTEPS,theslightbutsteadydeclineindemandfromthelate2020skeepstheoilpriceincheck.Fallingsupplyfromexistingfields,however,meansthereisnotalargeoverallreductioninprice.Anumberofmajorresource-holdershavepursuedactivemarketChapter2Settingthescene95managementstrategiesinrecentyearstokeeppriceshigherthantheywouldotherwisebe.Itisassumedthattheywillseektocontinuetodoso,meaningthemarginalprojectismoreexpensivethanimpliedbytheglobalsupply-costcurvealone.Table2.2⊳FossilfuelpricesbyscenarioSTEPSAPSNZERealterms(USD2022)20102022203020502030205020302050IEAcrudeoil(USD/barrel)10398Naturalgas(USD/MBtu)8583746042255.85.1UnitedStates9.932.34.04.33.22.22.42.0EuropeanUnion8.813.76.55.44.34.1China14.615.96.97.17.86.35.95.3Japan8.36.35.55.3Steamcoal(USD/tonne)67538.47.7UnitedStates122290EuropeanUnion1423369.47.8Japan153205CoastalChina464143262723676968535743987780596547968079626449Notes:MBtu=millionBritishthermalunits.TheIEAcrudeoilpriceisaweightedaverageimportpriceamongIEAmembercountries.Naturalgaspricesareweightedaveragesexpressedonagrosscalorific-valuebasis.TheUSnaturalgaspricereflectsthewholesalepriceprevailingonthedomesticmarket.TheEuropeanUnionandChinanaturalgaspricesreflectabalanceofpipelineandLNGimports,whiletheJapangaspriceissolelyLNGimports.TheLNGpricesusedarethoseatthecustomsborder,priortoregasification.Steamcoalpricesareweightedaveragesadjustedto6000kilocaloriesperkilogramme.TheUSsteamcoalpricereflectsminemouthpricesplustransportandhandlingcosts.CoastalChinasteamcoalpricereflectsabalanceofimportsanddomesticsales,whiletheEuropeanUnionandJapansteamcoalpricesaresolelyforimports.IntheAPS,thepolicyfocusoncurbingoilandgasdemandbringsdownthepricesatwhichthemarketfindsequilibriumfromlevelsin2022:theinternationaloilpricefallstoaroundUSD60/barrelin2050.IntheNZEScenario,oilandgaspricesquicklyfalltothecostsofthemarginalprojectrequiredtomeetfallingdemand,whichisaroundUSD40/barrelforoilin2030,beforedecliningfurthertoUSD25/barrelin2050.Thesepricescovertheoperatingexpensestoliftoilandgasoutofthefieldofthemarginalproducer,thecapitalexpenditureandoperatingcostrequiredinemissionsreductiontechnologies,aswellasupstreamtaxes.IEA.CCBY4.0.NaturalgaspricesIntheSTEPS,naturalgaspricesstaysomewhatelevatedrelativetopre-crisislevelsuntilthemiddleofthedecadeasglobalgasmarketscontinuetoadjustfollowingthelossofRussianpipelinegassupplytoEurope,alossthatisassumedtobepermanent.However,awaveofnewLNGexportcapacityfrom2025easesgasmarketbalances,andAsianmarketstakebackthedesignationofpremiummarketforLNG.AsnaturalgasdemandfirstplateausandthendecreasesintheSTEPSafter2030,importpricesstayaroundUSD8/MBtu.IntheUnitedStates,naturalgaspricesaveragearoundUSD4/MBtuduetodomesticproductionofgas.96InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IntheAPS,asharperreductioninEuropeannaturalgasdemandsoftenspricesfurther.LowergasdemandgrowthinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesandfiercecompetitionamongLNGsupplierstocapturemarketsharemeansthatby2030,pricesfornaturalgasimporterstendtowardstherangebetweenUSD6.5/MBtuandUSD8/MBtu.IntheNZEScenario,aglutofgassupplyformsinthemid-2020sasdemandstartstodeclinerapidlyinkeymarkets,andpricesinChina,JapanandtheEuropeanUnionfalltolevelslastseenatthe2heightoftheCovid-19pandemicin2020.Thisputsastrainonexportprojectsatthemargin,especiallyforthe40%ofexportprojectsthathavenotyetrecoveredtheirinvestedcapital.CoalpricesRobustcoalsupplyandlowernaturalgaspricessentcoalpricessteeplydownwardtowardstheendof2022,easinganunprecedentedperiodofmarkettightness.HighpricesduringtheenergycrisisinthewakeoftheRussianinvasionofUkrainehadpreviouslystrengthenedthebalancesheetsofcoalminingcompanies,providingthemwithanopportunitytoinvestinmaintainingand,insomecases,expandingcapacity.However,ourscenariosofferamixedpicture,atbest,forfuturedemandandprices.TheSTEPSofferssomecomforttocoalproducers,atleastinthenearterm,butdemandfallsinallscenarios,andpricesdeclinetowardstheoperatingcostsofexistingmines:thedeclineisfastestintheNZEScenario.CriticalmineralpricesReliableandsustainablesuppliesofcriticalmineralsandmetalssuchaslithium,nickel,cobaltandcopperarefundamentaltokeepcleanenergytransitionsaffordable.Vigorousdeploymentofcleanenergytechnologieshasmadetheenergysectorthemaindriverofgrowthinthecriticalmineralsmarket(IEA,2023f).Afterasurgeinpricesofthesecriticalmineralsin2021and2022,priceshavestartedtomoderate,butinmostcases,theyremainsignificantlyabovehistoricalaverages(Figure2.7).Wedonotyetmodelfulllong-termsupply-demandbalancesforcriticalmineralsinthesamewayasforfuels,butwedoundertakemarketmonitoringandscenariobenchmarking.Basedonthisanalysis,weexpectmedium-termmarketsformanyenergytransitionmineralstoremainunderpressureastheeconomyrecoversandcleanenergydeploymentcontinuestoaccelerate.Delaysorcostoverrunsremainasignificantpossibilityformanyannouncedsupplyprojects,anduncertaintyaboutthefutureavailabilityofhigherspecificationbattery-gradeproductsremainsasourceofconcern.Newcriticalmineralprojectsgenerallyinvolvehigherproductioncosts:thereisalonglistofpotentialplaysthatrequireelevatedmarginalcoststobringvolumesonstreamrangingfromlepidolite-basedlithiumandtosulfidic-basedcopper.Inaddition,supply-sideeventsmayinduceshort-termpricepressures:inearly2023therewereminesupplydisruptionsinBrazil,Chile,IndonesiaandPeru(theresultofunusuallyheavyraininBrazilandIndonesia),plusaluminiumproductioninChinawasdisruptedbyhydropowershortages.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter2Settingthescene97Figure2.7⊳Pricedevelopmentsforselectedenergytransitionmineralsandmetals,January2021toSeptember20231000LithiumNickelCobaltCopper250250Index(100=Jan2021)250800200200200600150150150400100100100200505050JanSeptJanSeptJanSeptJanSept20212023202120232021202320212023PriceIEA.CCBY4.0.2016-20averageAftersurgingin2021and2022,manycriticalmineralpricesstartedtomoderatein2023,buttheyremainhighrelativetohistoricalaveragesNotes:AssessmentbasedontheLondonMetalExchange(LME)LithiumCarbonateGlobalAverage,LMENickelCash,LMECobaltCashandLMECopperGradeACashprices.Nominalprices.Source:IEAanalysisbasedonS&PGlobal(2023).IEA.CCBY4.0.CarbonpricesGlobally,about23%ofenergy-relatedemissionsarenowcoveredbyacarbonpriceofsometype.Despitetheglobalenergycrisisandsignificantpricevolatilityinenergymarkets,carbonpricesincreasedin2022inabouthalfoftheexistingcarbonpricingschemes,severalnewinstrumentswerelaunched,andothersextendedtheirscope.TheEuropeanUnionsignificantlyincreasedtheambitionofitsETSandadoptedanewemissionstradingsystemforthebuildings,roadtransportandotherindustrysectors,whilealsointroducingaCBAMwhichwilllevyapriceoncarbonembeddedinimportedproductsinselectedsectors.ChinaincreasedthestringencyofitsnationalETS.IndonesiaannouncedthelaunchofitsownETSforthepowersector.Indiaintroducedframeworklegislationtodevelopanationalcarbonmarket.ThegovernmentinBrazilproposeddraftlegislationforanationalETS.Revenuesgeneratedfromemissionstradingsystemsandcarbontaxescontinueonanupwardtrend,withalmostUSD100billiongeneratedin2022(WorldBank,2023b).Nevertheless,mostcarbonpricesremainbelowthelevelthatweestimateisneededifthegoalsoftheParisAgreementaretobemet.Inourscenarios,theSTEPSincorporatesexistingandscheduledcarbonpricinginitiatives,whereastheAPSandtheNZEScenarioincludeadditionalmeasuresofvaryingstringencyandscope.IntheNZEScenario,forexample,carbonpricesarequicklyestablishedinallregions,98InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023risingby2050toanaverageofUSD250/tonneCO2inadvancedeconomies,andUSD200/tonneCO2inothermajoreconomies,e.g.China,Brazil,IndiaandSouthAfrica,withlowerpricelevelselsewhere.Aswithotherpolicymeasures,carbonpricesshouldbeintroducedonlywithcarefulattentiontothelikelyconsequencesanddistributionalimpacts.Thelevelofcarbonpricesincludedinourscenariosshouldbeinterpretedwithcaution:thescenariosincludeanumberofotherenergypoliciesandaccompanyingmeasuresdesigned2toreduceCO2emissions,andthismeansthatthecarbonpricesshownarenotthemarginalcostsofabatement(asisoftenthecaseinothermodellingapproaches).IEA.CCBY4.0.2.2.4TechnologycostsAfteranunbrokenrunofcostdeclines,pricesforsomekeycleanenergytechnologiesrosein2021and2022,largelyreflectinghigherinputpricesforcriticalminerals,semiconductorsandbulkmaterialssuchassteelandcement.Thishashadnegativeeffectsintheshorttermonthefinancialperformanceofsomemajorcleantechnologysuppliersandprojectdevelopers.Nevertheless,thepricesofallcleanenergytechnologiestodayaresignificantlylowerthanadecadeago:theyremaincompetitivewithfossilfuelalternatives.Signsareevidentin2023thatsomeofthecostpressuresareeasing,althoughtheriskoftightsupplychainsforkeycomponentsremains.Overall,weconsiderthatcleanenergytechnologycostswillcontinuetotrenddownward,andthatthereisstillconsiderablescopetoreduceimportantcostelementsthroughtechnologyinnovation,materialssubstitution,efficiencyimprovementsandeconomiesofscale.TheGECModelusedtogenerateourscenarioprojectionsincludesaverybroadrepresentationofenergytechnologies.Thecostsofthesetechnologiesevolveovertimeinthescenariosasaresultofcontinuedresearch,improvementsinmanufacturingandlearning-by-doing.Thesecostsarelinkedinturntolevelsofdeployment.Thelinkworksinbothdirections:lowercoststendtomeanhigherlevelsofdeployment,andhigherlevelsofdeploymenttendtoreducecosts.Thecostreductionsarenotlinear:atypicalcurvewillbesteepestintheearliestphasesofinnovationanddeployment(whenoverallcostsarestillhigh),andmuchflatteroncetechnologiesaremature.Policiesplayacrucialroleinthisprocess,particularlyindetermininghowquicklyinnovativecleantechnologiesarescaledupinsectorssuchasshipping,aviationandheavyindustry.Innovationalsohasanimpactontheprojectedcostsoffossilfuelsupply,butherethedownwardpressurefromtechnologylearningisoffsetbytheeffectsofmovingtomoregeologicallychallengingorremotedepositsascheaperandeasierresourcesaregraduallydepleted.Therearealsooffsettingpressuresinthecaseofsomecleantechnologies,forexample,newsitesforonshorewindmaybelessfavourableintermsofwindspeedsthanthosealreadyinoperation,andnewsitesforminingcriticalmineralsforbatterymanufacturingmayinvolvehigherproductioncosts.Butoveralltechnologycosttrendspointinthedirectionofincreasinglystiffcompetitionforfossilfuelsfromcleanenergytechnologiesacrossawiderangeofmarketsegments.Chapter2Settingthescene99Figure2.8⊳RecentcostdevelopmentsforselectedcleanenergytechnologiesIEAcleanenergyequipmentpriceindexAverageprices2502.5500Index(2019Q4=100)MillionUSD/MWUSD/kWhEVbatteries(rightaxis)2002.0400Batterystorage1501.53001001.0200500.5Windturbines100Solarpanels2014201620182020202220142016201820202022IEA.CCBY4.0.Cleanenergytechnologycostsedgedhigherin2022,butpressuresareeasingin2023andmaturecleantechnologiesremainverycostcompetitiveintoday’sfuelpricesettingNotes:Q4=fourth-quarter;MW=megawatt;kWh=kilowatt-hour.TheIEAcleanenergyequipmentpriceindextrackspricemovementsofafixedbasketofequipmentproductsthatarecentraltothecleanenergytransition,weightedaccordingtotheirshareofglobalaverageannualinvestmentin2020-2022:solarPVmodules(48%),windturbines(36%),EVbatteries(13%)andutility-scalebatteries(3%).Pricesaretrackedonaquarterlybasiswith2019Q4definedas100.Nominalprices.ThespeedatwhichnewtechnologiesentertheenergysystemisparticularlyimportantintheNZEScenario,whichreliesonanextremelyrapidpaceofinnovationinareassuchasnewbatterychemistries,carbondioxideremovaltechnologiesandammoniatofuelforships.Thisrequiresgovernmentstogiveahighprioritytoresearch,development,demonstrationanddeploymentactivitiesintheseareas,especiallyatatimewhencapitalmarketsarebecomingmoreexpensivetoaccess.Therearesomepositivesignsinrecentpolicyannouncementsthatthisishappening,althoughthecollaborationthatusuallyplaysanimportantpartinacceleratingknowledgetransferandsupportingrapiddiffusionofnewtechnologiescannotbetakenforgranted,especiallyintoday’sfractiousinternationalcontext.IEA.CCBY4.0.100InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter3PathwaysfortheenergymixAviewwithapeakSUMMARY•2022wasaturbulentyearforglobalenergymarkets,withenergyprices–notablyfornaturalgas–skyrocketinginEuropeandmanyotherpartsoftheworld.Theeffectsofthepriceshockonconsumerswerecushionedtoalargeextentbygovernmentinterventions.Globalenergydemandrose1.3%inlinewithitsrecentaverage.•Despitegeopoliticalfriction,volatilecommoditypricesanduncertaintyaroundcosts,transformativechangesinpartsoftheglobalenergysystemarecomingintoview.Electricvehicles(EVs)accountforaround15%ofcarsalestoday,andareoncoursetoreachashareof40%by2030intheStatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS).Arecord220gigawatts(GW)ofsolarcapacitywasaddedin2022,anddeploymentlevelsareprojectedtomorethandouble,whileheatpumpsmorethandoubletheirshareofheatingequipmentsalesintheSTEPSby2030.Theplannedboostinthemanufacturingcapacityofthesecleanenergytechnologies,iffullyrealised,appearsabletomeetmanyofthedeploymentmilestonesintheAnnouncedPledgesScenario(APS)and,inthecaseofsolarandbatteries,alsotoprovidewhatisrequiredintheNetZeroEmissionsby2050(NZE)Scenario.•Acceleratedscaleupofthecleanenergytransitionmeansthereisverylittlerunwayleftforgrowthinfossilfuels:forthefirsttime,demandforoil,naturalgasandcoaleachpeakinthethreeWorldEnergyOutlook-2023scenariosbefore2030.Theshareoffossilfuelsinprimaryenergydemanddeclinesfrom80%overthelasttwodecadesto73%intheSTEPSby2030,69%intheAPSand62%intheNZEScenario.•Electricitysupplybecomesprogressivelycleaneraslow-emissionssourcesincreasefasterthandemandineachscenario.SolarPVistheclearfrontrunner,butwindalsoscalesupdespitenear-termsupplychainchallenges,whilenuclearpower,otherrenewablesandlow-emissionsfuelsallmakeprogresstoo.•Electrificationofmobilityandheatacceleratesineachscenario,althoughnotatthesamerateaspowersectordecarbonisation.Energyefficiencyplaysakeyroleinallsectorsindeterminingtotalfinalconsumption.IntheSTEPS,consumptionincreasesbyanannualaverageof0.7%throughto2050;intheAPS,itpeaksinthelate2020sandthenslowlystartstodecline;intheNZEScenario,itfalls1%peryearfromtoday.•Hydrogenandcarboncapture,utilisationandstorage(CCUS)aremakingmuch-neededprogress.Thepipelineofprojectsshowsthatmorethan400GWofelectrolysisforhydrogenandover400milliontonnesofCO2capturecapacityarevyingtobeoperationalby2030.ThiscouldpotentiallymeetthemilestonesoftheAPSifallplannedprojectsgoahead,butcostinflationandsupplychainbottleneckscouldhamperprogress.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix101TransformativechangesoftheglobalRenewablesprovide70%energysystemarecomingintoviewofelectricitygenerationTheclosehistoricrelationshipbetweenglobalSolarPVbecomeslargesteconomicgrowthandfossilfueldemandisbeingsourceofelectricitygenerationloosenedbytheemergenceofanewcleanenergyeconomy.Basedontoday'spolicysettings,eachoftingunietlssthethreefossilfuelsseeapeakbefore2030.alfofheeafossilfuHsoldusSTEPSFossilfueldemandGDP197519777F0o%ssiolffeuleelcstrpircoitvyide19902002generation650millioncars2022ontheroadgloballyimprAonvenmuaelntavoevreargepaesftfidceiecnacdye<1%Annualaverageefficiency2030improvementsince2022>2%2040AdvancedeconomiesconsumeEmergingmarketand2050two-thirdsoffossilfuelsgloballydevelopingeconomiesconsume650millionelectriccarstwo-thirdsoffossilfuelsgloballyontheroadgloballyHalfofheatingunitssoldareheatpumpsorelectricheatersSolarPVandwindareSolarPVcontinuestogainmomentumandgrowsatanreshapingelectricitysupplyastonishingrateinallourscenarios,complementedbyrobustgrowthforonshoreandoshorewind.ScalinguppowersystemlexibilityiscriticaltointegratemoresolarPVandwindandacceleratetransitionsawayfromcoalandnaturalgas.HistoricalSTEPSAPSNZE35000TWhCoal20222022SolarPVWindNaturalgas205020502022205020222000ElectriicationisTheshareofelectricityintotalinalconsumptiongoesgatheringpacefrom20%todayto41%intheAPSandover50%intheNZEScenarioby2050.ElectriicationisakeycontributortoShareofelectricityinindustryreductionsinfossilfueldemand,alongsideeiciency23%27%40%49%improvementsandgreateruseoflow-emissionsfuels.ShareofelectricityinbuildingsShareofelectricityintransport35%50%58%70%1%11%27%51%20222050Coalinindustry(Mtce)Naturalgasinbuildings(bcm)Oilintransport(mb/d)161414638718695353STEPS64741525APS142022234NZE20503.1IntroductionAmidthewildfluctuationsinpricesandotherindicatorscausedbytheglobalenergycrisis,onedatapointstandsoutforbeingunremarkable:globalenergydemandroseby1.3%in2022.Thatenergydemandcontinuedtogrowbyamoreorlessaverageamountamidallthemarketturbulencehintsattheinexorableunderlyingdynamicsoftheenergysystem:theexpandingglobaleconomyandpopulationsimplyrequiremoreenergyservices.Thisshouldbethestartingpointforanyconversationaboutthefutureofglobalenergy,and3indeedthisiswhereourmodellingprocessbeginsinthisWorldEnergyOutlook(WEO).Thefirststepinproducingourscenarioprojectionsisnottolookatemissions,investmentorresources,buttolookindetailatdemandforenergyservices:howmuchlight,heatormobilitycommunities,industriesandcountriesaroundtheworldwillneedoverthedecadesto2050.Levelsofenergyservicesdemandevolveatroughlythesamerateacrosseachofourscenariosastheglobaleconomygrows,withtwoimportantnuances.Firstisthatthespeedatwhichtheworldmovestowardsuniversalaccesstomodernenergyvaries;achievementofthisgoalinvariablyleadstohigheruseofenergyservicesforlighting,cooling,cooking,andapplianceandequipmentuse.Secondisthatbehaviouralchangesandstrategiestoimprovematerialefficiency,adoptedtovaryingdegreesineachscenario,bringdowndemandforenergyservices,forexamplebysubstitutingshortcarjourneysforwalkingorcycling.Risingenergyservicesdemandisafeatureofeachscenario,butthatdoesnotnecessarilytranslateintorisingdemandforenergyorahigherlevelofemissions.Awiderangeoftechnologymixescanmeetneedsforheating,coolingormobility,eachwithdistinctiveimplicationsforcosts,resourceinputsandpollution.Weexploredifferentpathwaysinthischapter,examininghowinvestmentinarangeoftechnologiesandresourcescouldmeettheworld’sfutureenergyneeds,andhowpoliciesshapethechoicesthataremade.Thischapterstartswithanoverviewofthekeychangesintheglobalenergymixacrosseachscenario.Thisisfollowedbyfoursections:Firstisalookattrendsinglobalenergyfinalconsumptionintheindustry,transportandbuildingssectorsandhowdemandismetineachscenario.Secondisadetailedconsiderationoftheoutlookforelectricity,includingscenariospecificmixofgenerationtechnologiesandatvariationsindemandstemmingfromtheefficiencyofend-useequipmentandappliances.Thirdisalookatfuels:oil,naturalgas,coalandbioenergy.Fossilfuelsaccountforcloseto80%oftotalenergysupplytoday.Buttheoutlookto2050varieswidelyinthescenariosaccordingtothespeedatwhichcleanenergytechnologiesenterthesystem.IEA.CCBY4.0.Thefourthsectionconsiderstheevolutionofkeycleanenergytechnologies,focussingonsolarphotovoltaics(PV)andwind,electricvehicles(EVs),heatpumps,hydrogenandcarboncapture,utilisationandstorage(CCUS).Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix1033.2OverviewGlobaltotalenergydemandincreasesfromaround630exajoules(EJ)in2022to670EJby2030intheStatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS).Thiscorrespondstoanaverageannualgrowthrateof0.7%,aroundhalftherateofenergydemandgrowthoverthelastdecade.Demandcontinuestoincreasefrom2030throughto2050,withagrowthof16%inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesmorethanoffsettinga9%declineinadvancedeconomies.IntheAnnouncedPledgesScenario(APS),totalenergydemanddeclinesbyanaverageof0.1%peryearuntil2030,thankstofasterdeploymentofrenewables,increasedenergyefficiencyandmorerapidelectrificationthanintheSTEPS.IntheNetZeroEmissionsby2050(NZE)Scenario,electrificationproceedsevenfaster,improvingtheefficiencyoftheenergysystemandleadingtoadeclineinprimaryenergyof1.2%peryearto2030.Figure3.1⊳Globaltotalenergydemandbyfuelandscenario,2010-2050CoalOilNaturalgasRenewablesandnuclear(tcm)(EJ)(Mtce)(mb/d)6.048060001204500904.53603000603.02401500301.512020102050201020502010205020102050STEPSAPSNZEIEA.CCBY4.0.Low-emissionssourcesexpandsignificantlyand–forthefirsttime–allfossilfuelspeakandstarttodeclinebefore2030ineachscenarioNote:Mtce=milliontonnesofcoalequivalent;mb/d=millionbarrelsperday;tcm=trillioncubicmetres;EJ=exajoules.IEA.CCBY4.0.IneachofthescenariosinthisWorldEnergyOutlook,demandforeachofthemainfossilfuels–coal,oilandnaturalgas–reachesapeakbefore2030beforefallingback(Figure3.1).Coaldemanddeclinesfurthestandfastest:by2030,itfallsbyaround15%intheSTEPS,25%intheAPS,and45%intheNZEScenario.IntheAPS,ChinaandIndia'spledgestoreachnetzeroemissionsbefore2060andby2070respectivelydriveafasterdeclineincoaldemandthanintheSTEPS.IntheNZEScenario,abroaderphaseoutofunabatedcoalacrossregionsbeginsduringthe2020s,andthisleadstodemandfallingfasterthanintheAPS.OilpeakstowardstheendofthisdecadeintheSTEPSataround102millionbarrelsperday(mb/d).IntheAPSandtheNZEScenario,rapidandbroad-basedelectrificationandfast-growinguseof104InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023advancedbiofuelstogetherhastenthepeakinoildemand.Naturalgasdemandincreasesuntilthelate2020sintheSTEPS,reachingahighpointofaround4300billioncubicmetres(bcm).IntheAPS,naturalgasdemanddeclinesby7%between2022and2030aslow-emissionspowerexpandsrapidly,electrificationincreasesfasterthanintheSTEPSandgainsaremadeintermsofenergyandmaterialefficiencyinthebuildingsandindustrysectors.IntheNZEScenario,gasdemanddeclinesbynearly20%by2030inthefaceofverylargecleanenergyinvestmentsandefficiencygains.Fordecades,fossilfuelshavemetaround80%oftotalenergydemand.Rapidgrowthin3renewablesandnuclearbeginstoerodethisdominanceinthecomingyears,loweringtheshareofunabatedfossilfueldemandin2030to73%intheSTEPS,69%intheAPS,and62%intheNZEScenario.Avoidedenergydemandhelpstoenablethisshift:withoutfasterefficiencyimprovementsandbehaviouralchanges,morecleanenergysupplywouldgotowardmeetingrisingdemand,ratherthansubstitutingforfossilfuels.Allsourcesofrenewableenergyincreaseovertimeineachofthescenarios,althoughtheirrelativeweightsshift.Todaymodernbioenergy1accountsforoverhalfofrenewablesenergydemand,butsolarPVandwindexpandextremelyfastinthecomingyears,especiallyinthepowersector.TheinstalledcapacityofallrenewablepowersourcesmorethandoublesintheSTEPSandtheAPSby2030.IntheNZEScenario,theinstalledcapacityofrenewablestriplesby2030–akeymilestoneinthedrivetokeepthe1.5°Cgoalwithinreach.Figure3.2⊳Electricityintotalfinalconsumptionandlow-emissionssourcesinelectricitygenerationbyscenario,2010-2050Low-emissionselectricitygeneration100%2050STEPS75%APS50%2030NZE25%2022Electricitydemand:=10000TWh20100%25%50%75%100%ShareofelectricityintotalfinalconsumptionIEA.CCBY4.0.Powersectordecarbonisationadvancesmorerapidlythanend-useelectrificationineachscenario,butbotharekeypillarsofthetransitiontoacleanenergyeconomyNotes:TWh=terawatt-hours.Bubblesizeisproportionaltototalelectricitydemand.IEA.CCBY4.0.1Modernbioenergyincludesbiogases,liquidbiofuelsandsolidbioenergyexceptforthetraditionaluseofbiomass.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix105Today,low‐emissionssourcesofelectricitygenerationmainlyincludenuclear(9%ofelectricitygeneration)andrenewables(30%).Theshareofnuclearpowerremainsbroadlystableovertimeinallscenarios.Low-emissionselectricitygenerationoverallincreasesfrom39%oftotalelectricitygenerationtodayto57%by2030intheSTEPS,63%intheAPSand71%intheNZEScenario(Figure3.2).Thisconstitutesexceptionallyrapidgrowthbyhistoricstandards,whichreflectsthecosteffectivenessofsolarPVandwind,andtheirabilitytoattractinvestmentinmanufacturingcapacityaswellasindeployment.Theshareofelectricityinfinalconsumptionalsorisesfromitscurrentlevelof20%,whichmeansthatlow-emissionssourcesofelectricitygenerationareincreasingtheirshareofatotalwhichisitselfincreasing.IntheSTEPS,theelectricityshareoffinalconsumptionrisesto2030ataratesimilartothepast,beforeacceleratingslightlyandreaching30%by2050.IntheAPS,itrisesfaster,inlargepartduetothemorerapiduptakeofEVs,reaching40%by2050.IntheNZEScenario,itnears30%in2030andexceeds50%by2050,propelledinparticularbytheextremelyrapiddeploymentnotonlyofEVsbutalsoofresidentialandindustrialheatpumps.Figure3.3⊳EnergyintensityandenergypercapitainselectedregionsintheStatedPoliciesandAnnouncedPledgesscenarios,2022and2030GJperthousandUSD(2022,PPP)8300WorldUnited6225StatesEuropean4150UnionAfrica275MiddleEastLatinAmericaJapanandKoreaChinaIndiaSoutheastAsiaEurasiaGJpercapitaEnergyintensity:2022STEPS2030APS2030Energypercapita(rightaxis):2022STEPS2030APS2030IEA.CCBY4.0.AllregionsseeenergyintensitycontinuetodeclineovertimeintheSTEPSandtheAPS,whileenergyusepercapitaincreasesbeyond2030insomeregionsNotes:GJ=gigajoules;PPP=purchasingpowerparity.Energyintensityisdefinedastheratiooftotalenergysupplytogrossdomesticproduct(GDP)inPPPterms.Energypercapitaisdefinedastheratiooftotalenergysupplytopopulation.IEA.CCBY4.0.106InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Energyintensity2improvesatanaveragerateof2.2%peryearto2030intheSTEPS,comparedwith3%intheAPSand4.1%intheNZEScenario.Allscenariosimproveontheannualaveragerateof1.6%overthelastdecade,thankstomorestringentfueleconomystandards,additionalbuildingenergycodesandretrofittargets,improvedindustrialenergymanagementsystems,andthefurtherelectrificationofheatandmobility.Advancedeconomieshavelowerlevelsofenergyintensitytodaythanemergingmarketanddevelopmenteconomies,butthatisinlargepartafunctionofthemtypicallyhavingmoreservice-orientedeconomies.3Globalenergydemandpercapitaisaround80gigajoules(GJ)today,alevelthathasremainedbroadlystableoverthelastdecade(Figure3.3).ItremainsstableintheSTEPSto2030,butitdeclinesby7%intheAPSandby15%intheNZEScenario.Inadvancedeconomies,percapitademanddeclinesinallscenariosto2030.Inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,itcontinuestoriseintheSTEPSaseconomicgrowthdrivesanincreaseinenergyservicesdemand.Ineachscenario,energydemandpercapitainthisgroupofcountriesremainsbelowadvancedeconomiesovertheprojectionperiod.3.3TotalfinalenergyconsumptionTotalfinalenergyconsumption(TFC)is442EJtodayandissplitbetweenindustry(167EJ),buildings(133EJ),transport(116EJ)andotherend-uses(27EJ).IntheSTEPS,TFCrisesby1.1%peryearto2030andthencontinuestoriseataslowerratethroughto2050.IntheAPS,TFCrisesuntilthemid-2020sbeforestartingagradualdecline.IntheNZEScenario,TFCdeclinesbyanannualaverage0.9%everyyearfromnowto2050.Differencesinenergyefficiencygainsaretheprimarycauseofdivergenceintotalfinalconsumptiontrajectories.TheyaccountfornearlyhalfofthetotalenergysavingsintheAPSrelativetotheSTEPSby2030,withtheAPSreflectingadditionalretrofittargetsandupdatedbuildingenergycodes,morestringentfueleconomystandardsintransport,andupgradestoindustrialprocessesefficiency.IntheNZEScenario,year-on-yearenergyintensityimprovementsdoubleby2030(IEA,2023a).Differencesintherateofelectrificationareanotherimportantcauseofdivergenceinconsumptiontrajectories.IntheAPS,electrificationprovidesanother10%oftheenergysavingsrelativetotheSTEPSby2030.ElectrictechnologiessuchasheatpumpsandEVsprovideenergyservicesmoreefficientlythanrivaltechnologiesbasedonthedirectcombustionoffossilfuels,anduseoftheseelectrictechnologiesexpandsfasterintheAPSandtheNZEScenariothanintheSTEPS.TheshareofelectricityinTFCincreasesfromaround20%todayby2percentagepointsintheSTEPSby2030,by4percentagepointsintheAPS,andby8percentagepointsintheNZEScenario:itisthesedifferencesthatdelivertheIEA.CCBY4.0.2Theenergyintensityimprovementrateisdefinedastheannualreductionofenergyintensity,ortheratioofenergysupplytoGDPinpurchasingpowerparity(PPP)terms.Inourscenarios,PPPfactorsareadjustedasdevelopingcountriesbecomericher.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix107additionalenergysavingsintheAPSandtheNZEScenario(Figure3.4).Railandroadtransport,ironandsteel,aluminium,lightindustriesaswellasheatingandcookinginbuildingsseethemostsubstantialincreasesinelectricityshareacrossscenarios.Figure3.4⊳Shareofglobaltotalfinalconsumptionbyselectedfuelandscenario,2022-205060%STEPSAPSNZE40%20%202220502022205020222050OilElectricityNaturalgasCoalModernrenewablesHydrogenandhydrogen-basedfuelsIEA.CCBY4.0.ThecontributionsofelectricityandmodernrenewablesincreasewhiletheshareoffossilfuelsdeclinesineachscenarioNote:Modernrenewablesreferstothedirectuseofrenewableenergysourcesexcludingthetraditionaluseofbiomass.Thedirectuseofrenewablesintotalfinalenergyconsumption–includingmodernbioenergy,solarthermalandgeothermal–expandssignificantlyineachscenario,by3%peryearintheSTEPS,7%intheAPS,and9%intheNZEScenarioby2030.Low-emissionshydrogenandhydrogen-basedfuelsfinalconsumptionincreasesby200petajoules(PJ)(ofwhich1.6milliontonnes[Mt]ofhydrogen)intheSTEPSby2030and1000PJ(ofwhich6Mtofhydrogen)intheAPS,withgrowthconcentratedinhard-to-abatesectorsincludingaviationandshipping.Renewablesandlow-emissionsfuelscontribute8%oftheadditionalenergysavingsintheAPScomparedtotheSTEPSby2030.IEA.CCBY4.0.3.3.1IndustryIndustryisthemostenergyconsumingandCO2emittingend-usesector.Itaccountsfor38%ofTFCand47%ofCO2emissions(includingemissionsfromelectricityandheat).Energy-intensiveindustries–ironandsteel,chemicals,non-metallicminerals,non-ferrousmetalsandpapersectors–accountforalmost90%ofdemandforcoalusedinindustry,morethan70%foroilusedinindustryandalmost55%fornaturalgas(Figure3.5).Energy-intensiveindustrieshaveincommonhigh-temperatureneedsandlong-livedassets.Otherindustry,or108InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023non-energy-intensiveindustries,whichincludeslightindustriessuchasfoodandtextiles,havelowertemperatureneedsandaccountfortheremaining30%ofdemandintheindustrysector.Itsenergymixismainlyelectricity(37%),naturalgas(20%),oil(15%)andbioenergy(14%).Figure3.5⊳Energydemandbyfuelforenergy-intensiveandotherindustriesbyscenarioEnergy-intensiveindustriesElectricity3202220502030CoalSTEPSUnabatedAPSWithCCUSNZENon-energyuseSTEPSOilAPSUnabatedNZEWithCCUSOtherindustryNon-energyuse202220502030NaturalgasSTEPSUnabatedAPSWithCCUSNZENon-energyuseSTEPSWaste:non-renewableAPSDistrictheatNZEHydrogenBioenergy50100150SolarthermalEJGeothermalIEA.CCBY4.0.Achievingclimateambitionsinindustryreliesonelectrification:electricheatersandheatpumpsinlightindustries,andelectricprocessesandonsitehydrogenforsteel,ammoniaandmethanolNotes:CCUS=carboncapture,utilisationandstorage;EJ=exajoules.Wherelow-emissionshydrogenisproducedandconsumedonsiteatanindustrialfacility,thefuelinput,suchaselectricityornaturalgas,isreportedasfinalenergyconsumption,notthehydrogenoutput.IEA.CCBY4.0.Industrialproductionunderwentsignificantdisruptionin2022asaresultofRussia’sinvasionofUkraineandaslowdownintheconstructionsectorinChina.Globalcementproductionwasdownby5%andsteelproductionby4%,thoughdemandforchemicalsremainedstable,andinthecaseofmethanolitactuallyrose.Thesedownwardpressuresonindustrialproductiondonotpersist:intheSTEPS,productionofallmainindustrialmaterialsincreasesby2030,includingethylene(27%higher),methanol(17%higher),aluminium(13%higher)andpaper(12%higher),andsteelandammonia(each10%higher)andcement(8%higher).TheriseinproductionmainlyoccursindevelopingAsia.Progressindevelopingefficiencyandlow-emissionspoliciesforindustryhasbeenuneven,withpatchyadoptionofcarbonpricingandminimumenergyperformancestandards(MEPS)inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies(Table3.1).SomegroupsofindustrialChapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix109stakeholdershavetakentheinitiativeandsettargetstoproducelow-emissionsmaterials.Forexample,steelpurchasersintheFirstMoverCoalitionhavepledgedthatat“atleast10%(byvolume)ofalloursteelpurchasedperyearwillbenear-zeroemissions[…]by2030”.Table3.1⊳KeyenergydemandpoliciesforindustrybyregionCarbonMinimumenergyPublicprocurementFundsforpricingindustrialperformanceoflow-emissionsinnovationstandardsformotorsmaterialsUnitedStates●●●●LatinAmericaand○◔○◔theCaribbeanEuropeanUnion●◕◕●Africa○○○◔MiddleEast○◔○○Eurasia○○○◔China●●●●India○●○○JapanandKorea●●●●SoutheastAsia○◔○○Shareofcountrieswithineachregionwithpolicycurrentlyimplemented:○<10%◔10-39%◑40-69%◕70-99%●100%IEA.CCBY4.0.IntheAPS,measurespromotingmaterialefficiency,suchaslifetimeextensionofbuildingsandgoods,lightweightingorsmartdesign,helpcurbglobaldemandforindustrialmaterialdemandcomparedwiththeSTEPS.Theimpactofthesemeasuresbuildsovertime.Forexample,globalcrudesteeldemandis5%lowerintheAPSthanintheSTEPSin2035and13%lowerby2050.IntheNZEScenario,morewidespreaddeploymentofsuchmeasuresleadssteel,cementandmethanoltopeakwithinthenextfifteenyears.Coaldemandintheindustrysectorpeaksinthemid-2020sintheSTEPS,fallsbelowthe2022levelin2035andis10%belowthislevelby2050,withreductionsindemandinChinaandadvancedeconomiesmorethanoffsettingincreasesintherestofdevelopingAsia,AfricaandLatinAmericaandtheCaribbean.Themainreasonfortheoveralldeclineistheriseofsecondarysteelproduction,mostlyrelyingonelectricity,inlieuofconventionalprimarysteelproductionusingcokingcoal.Inallscenarios,scrapavailabilitylimitsthedeploymentofsecondaryproduction.InboththeSTEPSandAPS,theshareofsecondaryproductiondoublescomparedtotodaytomorethan40%worldwide.IntheAPS,electrificationoflightindustries,hydrogen-basedironproductionandhigherrelianceonbioenergymeanthatcoal110InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023useinindustryin2050is55%lowerthanintheSTEPS,andalmost20%ofcoalusetakesplaceinplantsequippedwithCCUS.Oiluseinindustry,mostlyforpetrochemicalproduction,increasesby2.8mb/dto2030intheSTEPS,withmostofthegrowthtakingplaceinChina,SoutheastAsiaandtheMiddleEast.IntheAPS,bansonsingle-useplasticsandthewidespreadcollectionofplasticshelptocurbtheincreaseinoildemandto0.8mb/dfrom2022to2030,andtobringitdownby3.6mb/dby2050comparedto2030.Theshareofnon-energyuse,i.e.chemicalfeedstockandanodeproduction,inindustryoildemandrisesfrom60%todaytoover65%in2030and80%in32050.Naturalgasinindustryisusedinawiderangeofapplications:athirdisconsumedinotherindustry,especiallyinfoodandmachinery,andmorethanafifthgoestowardstheproductionoffertiliser.IntheSTEPS,developingAsia,ledbyChinaremainsthelargestsourceofgrowthfornaturalgasdemandinindustryuntil2030,althoughitsrateofgrowthismuchslowerthanoverthepastdecade.Indiabecomesthelargestsourceofgrowthafter2030,whiledemandintheEuropeanUniondeclinesfurther.Inallscenarios,electricityisthefuelthatincreasesthemostinnon-energy-intensiveindustries,andsustainablebioenergytakessecondplace.Increasedelectrificationplaysasignificantpartindecarbonisingenergy-intensiveindustries,whetherthroughdirectelectrificationorthroughtheuseofhydrogenproducedusingelectrolysers.IEA.CCBY4.0.Howcanindustrialprocessesachievehighlevelsofelectrification?Asoftoday,mostelectricityinindustryisusedformotor-drivensystems.Electricityhasthepotentialtoprovideheatingacrossawiderangeoftemperaturelevelsforheating,includingthroughheatpumpsforlow-temperatureapplicationsandelectricarcfurnacesforhightemperature(asitalreadydoesforsecondarysteelmaking).Italsohasthepotentialtoprovidepowerforarangeofindustrialprocessesincludingaluminaelectrolysis,whichproducesaluminiumandelectrowinning,whichproducescopperandnickel.Electrificationreducesenergydemandbecauseitisgenerallymoreefficientthatthefossilfuelprocessesthatitreplaces.Totheextentthatitdrawsonlow-emissionssourcesofpower,electrificationalsodrivesdownCO2emissionsfromtheindustrysector.Around65%ofelectricityusetodayinindustryisformotor-drivensystems.Motorsareusedtodrivepumps,fans,compressedairsystems,materialhandling,processingsystemsandmore.Overthelastdecade,motor-drivensystemsaccountedforalmost60%(630terawatt-hours[TWh])ofgrowthinelectricitydemandinlightindustries,andtheyaresettobethelargestsourceofelectricitydemandintheindustrysectorintheyearsahead.Thereissomepotentialtoimproveenergyefficiencynotonlybyupgradingthemotorsthemselvesbutalsobymakingotherimprovementstothesystem,forexamplebydownsizingelectriccapacitytomatchtheservicerequired.Sixty-twocountrieshaveimplementedMEPSforindustrialelectricmotors,coveringmorethanhalfoftheglobalindustrialmotorfleetin2022:morewidespreadadoptionofMEPSwouldbringfurtherenergyefficiencygains.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix111Electrificationofprocessheatincreasesinallscenarios,thoughatvariousspeeds(Figure3.6).Inthelightindustrycategory,over700TWhorone-fifthofelectricityiscurrentlyusedforheatingpurposes,andthisrisestoover800TWhin2030and1000TWhin2050intheSTEPS.IntheAPS,theelectrificationofprocessheathappensmuchfaster:the1000TWhmarkispassedby2030,anddemandreaches1800TWhby2050.TheAPSalsoseesinnovativeprogresstowardsthedirectelectrificationofenergy-intensiveprocessessuchasaluminarefining,secondaryaluminiumproduction,kilnsandsteamcrackers.Figure3.6⊳Electricitydemandbyselectedindustrysub-sector,end-useandscenario,2022-2050Bysub-sectorByend-use16ThousandTWhMethanol100%Other12LightingAmmoniaOtherelectro-8chemicalPulpandpaper75%ElectrolyticH₂4CementProcesscoolingProcessheatAluminiumMotor-drivensystemsIronandsteel50%OtherlightindustriesFoodand25%tobaccoMachinery20222022STEPSSTEPSAPSAPSNZENZESTEPSSTEPSAPSAPSNZENZE2030205020302050IEA.CCBY4.0.Allindustrysub-sectorsdependonelectricityanddemandrisesnotablyforprocessheatandhydrogenintheAPSandNZEScenarioNotes:TWh=terawatt-hours;H2=hydrogen.Machinerysub-sectorreferstotheproductionofmachinesandtheircomponents.Otherelectro-chemicalincludesprimaryaluminiumproduction,chlor-alkaliindustryandsomeorganicsynthesis.IEA.CCBY4.0.Theuseofelectricityinsteel,ammoniaandmethanolproductionislikelytodependontheonsiteproductionanduseofelectrolytichydrogen.Thereisscope,forexample,forhydrogentobeusedinancillaryprocessesinvariousheavyindustries,includingsemi-finishingforsteelandaluminium.Theseimportantnear-zero-carbonoptionsaremostlydeployedintheAPSandtheNZEScenario.In2050,globalonsiteelectrolytichydrogendemandinindustryreaches36MtintheAPS,consuming1600TWhofelectricity:thehydrogenisusedtoproducearoundaquarterofiron,ammoniaandmethanol.Electricityisalsousedinotherelectro-chemicalprocessesmostlyforprimaryaluminiumproduction.ElectricityuseforprimaryaluminiumproductionincreasesintheAPSuntil2040,risingto700TWh,thendeclinesasexpandingscrapavailabilityleadstorisinglevelsofsecondaryproduction.112InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20233.3.2TransportEnergydemandintransportroseby4%in2022asitcontinuedtoreboundtowardspre-Covidlevels,withoilaccountingfor90%ofthisgrowth.Thiswasmainlydrivenbytheaviationsector,whichsaw20%year-on-yeargrowth:despitethis,aviationenergydemandremainsaquarterbelowits2019level.Electricitydemandfromroadtransportwasnearly60%higherin2022thanin2019,andthemarketshareofelectriccars3innewregistrationsreached14%.IntheSTEPS,theglobalcarfleetincreasesbyover15%by2030,andasimilarincreaseis3projectedforbuses.Thefleetoftwo/three-wheelers4increasesbyover20%andthenumberoftrucksbyover10%overthesameperiod.Aviationactivitydoublesfromtoday’slevel,railpassenger-kilometresincreaseby36%,andshippingtonne-kilometresincreasebyalmost20%in2030.IntheAPS,modalshiftsawayfromprivatetransportationlessenthegrowthofthecarfleetandleadtorailpassenger-kilometresbeingover5%higherin2030thanintheSTEPS.IntheNZEScenario,strongermeasurestominimiseemissionsreducetheactivityinaviationby20%andthecarstockby15%comparedtotheSTEPSin2050:thesemeasuresincludebehaviourchangesandtheexpansionofhigh-speedrail.Figure3.7⊳Energydemandintransportbyfuelandscenario,2022-20502030RoadOil2022NaturalgasSTEPSBioenergyAPSElectricityNZEHydrogenSTEPSHydrogen-basedAPSfuelsNZE2030Non-road2022STEPSAPSNZESTEPSAPSNZE255075100EJIEA.CCBY4.0.Electricityiskeytodecarbonisingroadtransportandmeetsnearly40%ofdemandintheAPSby2050;low-emissionsfuelsmakeinroadsmainlyinaviationandnavigationNotes:Non-roadtransportincludesaviation,shipping,rail,pipelineandnon-specifiedtransportation.Hydrogenandhydrogen-basedfuelsareproducedvialow-emissionspathways.IEA.CCBY4.0.3Electriccarsincludebothbatteryelectricandplug-inhybrids.4Two/three-wheelersincludeelectricandnon-electricscootersbutnotbicycles.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix113By2030,theshareofoilinroadtransportenergydemanddropsfrom92%todayto88%intheSTEPS,84%intheAPS,and78%intheNZEScenario(Figure3.7).Atectonicshifttowardselectromobilityandtheincreaseduseofbiofuelsdrivethisdrop.Electricitydemandforroadtransportrisesbymorethan12-timesby2030intheSTEPSandover15-timesintheAPS.Supportedbyphase-outdatesforinternalcombustionengine(ICE)vehiclesandincentivesforelectromobility,EVsaccountfornearly20%oftotalroadvehicle-kilometresintheAPSin2030.However,sincetheyarethree-tofour-timesmoreefficientthanICEvehicles,theyonlyaccountfor5%ofroadtransportenergydemand.Table3.2⊳KeyenergydemandpoliciesfortransportbyregionFueleconomyZEVincentivesICEphaseoutSupportforSAFCarsTrucksCarsTrucksCarsTrucksUnitedStates●●●●◔◔●LatinAmericaand◔○◑○○○○theCaribbeanEuropeanUnion●●●●●○●Africa○○○○○○○MiddleEast○○◔○○○○Eurasia○○◔○○○○China●●●●○○○India●●●○○○○JapanandKorea●◑●◑○○◑SoutheastAsia◔○◑○○○◔Shareofcountriesorjurisdictionswithineachregionwithpolicycurrentlyimplemented:○<10%◔10-39%◑40-69%◕70-99%●100%Notes:ZEV=zeroemissionsvehiclesincludingEVsandfuelcellvehicleswithzeroemissionsatthetailpipe.ICE=internalcombustionengine.E-fuels-poweredvehicles=conventionalvehicleswhichrunonelectrofuels.SAF=sustainableaviationfuels.Inregionswithonlyonecountry,unlessthereisanationalpolicyinplace,sharesareshownforsubnationaljurisdictions.IntheEuropeanUnion,theICEvehiclephase-outpolicyexemptse-fuels-poweredvehicles.IEA.CCBY4.0.Electrificationoftruckssofarhasmadeslowerprogressthantheelectrificationofcars,inpartbecauseithasattractedlesspolicysupport(Table3.2).Batteryelectrictruckshaveneverthelessseennotableadvancements,particularlyasmedium-dutytrucksandothervehicleswithrelativelyshort,fixedroutes.IntheSTEPS,themarketshareofelectrictrucksrisesfrom3%ofglobaltrucksalestodaytonearly20%by2030intheSTEPSandto25%intheAPS.Theelectrificationoftwo/three-wheelersproceedsmuchmorerapidly,inpartbecauseoftheirlimitedpowerneedsandtherelativelymodestupfrontcostincreasecomparedto114InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023conventionalpowertrains.Theelectrictwo/three-wheelersfleetin2030ismorethanfour-timeslargerthantoday.Innon-roadtransportenergydemand,theshareofoilremainsnearlyattoday’slevel(85%)inboththeSTEPSandAPSby2030;itdropstoaround75%intheNZEScenario.Railisthemostelectrifiedtransportmodetoday,andtheshareofoilinenergydemandinrailfallsfrom53%todayto46%and40%intheSTEPSandAPSduetoincreasedrailelectrification.IntheNZEScenario,thespeedandbreadthoffurtherelectrificationreducestheshareofoilintotalraildemandtoaround30%by2030.Oilcontinuestoaccountformostoftheenergydemand3inaviationto2030inboththeSTEPSandAPS.Thesameisbroadlytrueforshipping,althoughtheshareofoilinenergydemandinshippingstartstodeclineslightlyby2030asnaturalgasandbioenergybegintomakeinroadsintoitsenergymix.IntheSTEPS,togethertheyaccountfor4%ofenergydemandinshippingby2030.IntheAPS,theyaccountfor6%ofdemand,whileammonia,hydrogen,electricityandsyntheticmethanolreducetheshareofoilbyanother4percentagepoints.IntheNZEScenario,theshareofoilinenergydemandinshippingfallsto80%by2030.TheEuropeanUniondecisiontoincludemaritimeemissionsintheEUEmissionsTradingSystem(EUETS)andtheInternationalMaritimeOrganizationrevisionofitsgreenhousegasstrategybothboosteffortstodecarboniseshipping.TheFuelEUMaritimeinitiativeandtheUSCleanShippingActsupporteffortstodothesamebyincentivisingtheuseofcleanerfuels.IEA.CCBY4.0.AreweheadingtowardstheendoftheICEage?Oiluseforroadtransportisresponsiblefornearly45%ofglobaloildemand.Itcurrentlytotalsaround41mb/d,withcarsaccountingfor21mb/dandtrucksfor16mb/d.ICEcarsalesgrewbyanannualaverageof3.4%from2010to2017,peakingat85millionvehicleregistrationsin2017.TheCovid-19pandemiccausedsalestodipby13%in2020.Sincethen,salesofICEcarshaverecoveredonlymarginallywhilesalesofelectriccarsshotupfrom3millionin2020toover10millionin2022.Intheyearsahead,totalcarsalesaresettoincreasebyover30%toreachnearly100millionby2030.Aroundtwo-thirdsofthiscomesfromemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,inparticularChina,IndiaandIndonesia.ButtheriseofEVsmeansthatsalesofICEcarsdoesnotreverttothe2017peaklevel(Figure3.8).IntheSTEPSandAPS,widespreadpolicysupporthelpssalesofelectriccarsworldwidetocontinuetheirimpressiveexpansion.Morethan50countries,hometoaround60%oftheworldpopulation,havepoliciesinplacetoincentivisetheuptakeofEVs.Around30countrieshavesettargetdatestophaseoutICEvehicles,andseveralothersareconsideringsimilaraction.Inaddition,automobilemanufacturershaveplanstoreleaseover150newelectriccarmodelsinthecomingyears,andsomehavemadetheirownnetzeroemissionscommitments.EffortsarebeingmadetoestablishlocalEVmanufacturinghubsinanumberofcountriesincludingIndia,IndonesiaandThailand,providingafurtherboostfortheirswitchfromICEvehiclestoEVs.Thesemeasuresmeanthatsalesofelectriccarscontinuetheirimpressivegrowth.By2030,salesofICEcarsdeclinetoaround60millionintheSTEPSand55millionintheAPS.WiththisChapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix115structuraldeclineofICEvehiclesinroadvehicles,oildemanddoesnotrecovertoitspre-pandemiclevels:itstandsataround41mb/dby2030intheSTEPSandaround38mb/dintheAPS.Electriccarscurrentlydisplace0.4mb/dofoildemand,andthisrisestonearly4mb/dbytheendofthisdecade,bringingenergysecuritybenefitstooilimportingcountriesandreducingthenumberofconsumersexposedtovolatileoilprices.Figure3.8⊳NewpassengercarregistrationsbytypeandpassengercaroildemandintheStatedPoliciesandAnnouncedPledges125scenarios,2010-2050STEPSAPSMillionpassengercars1225525mb/d100102002075715515505100102525552010202220302050202220302050ICEcarsZero-emissionscarsPassengercaroildemand(rightaxis)IEA.CCBY4.0.Registrationsofnewconventionalcarspeakedin2017;policiessupportingelectromobilitydeliverasharpdeclineinoildemandfromroadtransportIEA.CCBY4.0.InChina,salesofelectriccarsaccountedfor29%ofthemarketin2022;theyaresettoreachover35%in2023and65%by2030intheSTEPSwiththesupportoftaxexemptions.SalesofelectriccarsintheEuropeanUnionmadeupover20%ofthemarketin2022,andthelatestCO2standardsadoptedforpassengercarslooksettohelpincreasethatmarketsharetoover60%by2030.IntheUnitedStates,electriccarsalessawamorethan55%year-on-yearincreasein2022andnowrepresentaround8%ofthemarket.Thesalesshareincreasesto50%by2030astheInflationReductionActandBipartisanInfrastructureLawhelptoboostaffordabilityandsupporttheroll-outofcharginginfrastructure.Strongpolicysupport,particularlyinChina,helpedEVstobecomeincreasinglycompetitiveinthemarketandtobecomecentraltothechallengetoreduceemissions.ActionisnowneededtoensurerapiddeploymentofEVchargingfacilitiesandtoenhanceelectricitynetworkssothatinadequateinfrastructuredoesnotholdbacktheirexpansion.Actionisalsoneededtocontinuetherapiddeploymentofrenewablesinelectricitygeneration:theemissionsbenefitsoftheshifttoEVsdependupontheavailabilityoflow-emissionselectricity.116InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Howcanemissionsfromaviationbereduced?Aviationaccountsforover2%ofenergy-relatedemissionsandiscurrentlydominatedbyoil.Avarietyofparallelstrategiesareneededtodecarboniseaviation.Improvementsinaerodynamicsandlightweightingmaterialshaveledmodernairplanestobenearly20%moreefficientthanthosebuiltaroundadecadeago.Therewillbefurtherimprovementstocome,buttechnology,materialanddesignchangesinaeronauticsarecharacterisedbylongimplementationtimes.Sustainableaviationfuels(SAF)offerscopetoreplaceoilandreducedememisasinodnsin,bauvitatthioeny.aInrethsetilNlvZeErSyceexnpaernios,ivbeehaanvdiotuordacyharnegperessaernetalnesosththeranke0y.0le1v%ero,fweintheorguyt3them,totalaviationactivitywouldbe10%higherby2030andover20%higherby2050.Figure3.9⊳Energydemandinaviationbyfuelandscenario,2022-2050,andannualfuelintensityimprovementrate,2019-2050Energydemand2019-50annualintensityimprovement303%20EJElectricity2022STEPSHydrogenAPSNZESynthetickeroseneICAOtargetSTEPSBiojetkerosene2%APSNZEOilStockturnover101%STEPSAPSNZE20302050IEA.CCBY4.0.Acceleratingtheuseofsustainableaviationfuelsandreducingin-flightenergydemandthroughefficiencymeasuresarekeytocurbingoildemandgrowthNote:TheInternationalCivilAviationOrganization(ICAO)setanaspirationalgoalin2010toimprovefuelintensity(measuredperrevenuetonne-kilometre)by2%peryearto2050.IEA.CCBY4.0.Eachyear,thefuelintensityoftheglobalaircraftfleetimprovesbyaround1%duetostockturnoverasoldermodelsareretired.IntheSTEPS,thewidespreaduseofcost-effectiveoperationalefficiencymeasuressuchassingleenginetaxiingandoptimisedflighttrajectoriesincreasesthisefficiencyrateto1.3%eachyearthroughto2050.TheAPSseesthisrisetoover1.4%asaresultoffurtherimprovementsincludingelectrictaxiingandformationflying.TheNZEScenarioreachestheInternationalCivilAviationOrganization(ICAO)goalofa2%annualreductioneachyearuntil2050:thisassumesvitaladditionalsupportforresearchanddevelopmentforrevolutionaryairframesandhybridelectricaircrafts(Figure3.9).Efficiencyimprovementshaveaveryimportantparttoplay,buttheyofferonlyapartialanswertotheproblemofaviationemissions.TheycannotevenentirelycounterbalanceChapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix117growthindemandforaviation,whichisexpectedtoleadtoanincreaseofaround4%inflightactivityeachyearuntil2050.Thispointstoanurgentneedforthedevelopmentanddeploymentoflowercarbonfuels.SAFlooktobethemostpromisingoption:whetherintheformofbiojetkeroseneorsynthetickerosene,theyaredrop-infuelsthatcanbeblendedwithconventionaloilproductsatratesofupto50%.Theyalsohavethepotentialtobeusedontheirown:manufacturersandairlinesarecurrentlytestingflightsthatrunsolelyonSAF.AlthoughSAFoff-takeagreementsmorethandoubledinvolumebetween2021and2022,signallinggrowingdemand,highcostsremainabarriertowidespreadadoption,andtheannouncedprojectpipelinecoversonly1-2%ofglobalaviationdemandby2027(IEA,2022a).Bio-keroseneproductioncurrentlycoststwiceasmuchasconventionalkerosene,andsynthetickerosenefour-timesmore.Expandingsupplywillhelpreducecosts,buttheaveragepriceofSAFisstillexpectedtobearoundtwotimeshigherthanthatofconventionalkerosenein2030.IntheSTEPS,biojetkerosenemakesup2%oftotalenergydemandinaviationin2030and6%in2050,comparedwithover5%and37%respectivelyintheAPS,and11%and70%respectivelyintheNZEScenario.Synthetickerosenedemandin2050intheNZEScenarioisnearlydoublethelevelsintheAPS.ThehigherlevelsofdemandintheAPSandtheNZEScenarioassumehigherlevelsofsupportforSAFfromgovernmentsandincreasedindustryinvestmentsinthecontextofbroaderpolicyframeworksthatgiveahighprioritytoreducingemissions.Therearesomegroundsforoptimismonthisscore,sincetherearealreadyanumberofpoliciesfocussedonSAF,thoughthedetailhasstilltobeworkedthroughinmanycases.TheUSInflationReductionActprovidestaxcreditsforSAF,andthissupportcouldenableproductiontoreach3billiongallons(0.2mb/d)in2030and35billiongallons(2.3mb/d)by2050,whichwouldbeenoughtofuelallUSflightsby2050.SAFarealsosupportedbyEUInnovationFundgrants,Japan’splannedmandateforSAFtoprovide10%ofaviationfueluseby2030,theUKJetZeropledgetodecarboniseaviationby2050,andReFuelEUAviation’smandatefortheshareofSAFinaviationfueltoreach70%by2050.However,thereisalimitedsupplyoftheresourcesusedtodaytoproducesustainablebiofuels,includingcookingoilandwasteanimalfats,andafeedstockcrunchcouldhampergrowthintheshortterm.Tomeetadditionalbiofueldemandovertime,alternativeproductionpathwaysusingmaterialssuchasmunicipalsolidwasteandagriculturalandforestryresiduesneedtobecommercialised.GovernmentsupportandprivateinvestmentsarealsoneededforthedevelopmentandcommercialisationofSAFtechnologiesthathavelowtechnologyreadinessandhighcoststoday,notablysynthetickerosene.IEA.CCBY4.0.3.3.3BuildingsTotalenergyconsumptioninthebuildingssectorincreasedonaverageby1%peryearoverthelastdecadeandreached133EJin2022(Figure3.10).Naturalgasdemanddeclinedin2022followingRussia’sinvasionofUkraineandamildwinter,withthedeclinemostnotedinEurope,butnaturalgasstillmet23%ofenergydemandinbuildingsworldwide.Electricity118InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023nowaccountsforoverone-thirdofenergydemandinthebuildingssector:itssharehassteadilyincreasedwithexpandingownershipofappliancesandairconditioners,andelectrificationofheatingandcooking.Modernbioenergymeets4%ofenergydemandinbuildings,andotherdirectusesofrenewables,intheformofsolarthermalandgeothermalheating,morethandoubledoverthelastdecadetonowaccountfor2%ofdemand.Figure3.10⊳Buildingssectorenergydemandbysourceandend-use20502030byscenario,2022-20503ByenergysourceCoal2022OilNaturalgasSTEPSElectricityAPSDistrictheatNZETraditionaluseofbiomassModernsolidbiomassSTEPSOtherrenewablesAPSLow-emissionsgasesNZEOtherByend-use205020302022SpaceheatingWaterheatingSTEPSCookingAPSAppliancesNZESpacecoolingLightingSTEPSOtherAPSNZE4080120160EJIEA.CCBY4.0.Energyconsumptioninthebuildingssectorincreasessteadilyto2050intheSTEPSbutdeclinesintheAPSandNZEScenario;electricityexpandsitsshareineachscenarioNotes:Low-emissionsgasesincludehydrogenandbiogases.Otherrenewablesincludesolarthermalandgeothermal.Otherincludesbioliquidsandnon-renewablewaste.Otherincludesthetraditionaluseofbiomassanddesalination.Spaceheatingandcoolingprojectionsreflectexpectedchangesinclimate.IEA.CCBY4.0.IntheSTEPS,globalbuildingsenergydemandincreasestoalmost140EJin2030and160EJin2050,primarilybecausethenumberofhouseholdsincreasesfromaround2.2billiontodayto3billionby2050,withthelargestincreasesinAfricaandtheAsiaPacific.Globalfloorareaofresidentialbuildingsexpandsfromaround200billionsquaremetrestodayto310billionin2050.IntheAPS,energydemanddeclinesovertimedespitetheseupwardpressuresonenergydemand,thankstoimprovedefficiencyinbuildingenvelopesandtechnologies.By2030,energydemandinbuildingsis12%lowerintheAPSthanintheSTEPS.Theshareofelectricityinbuildingssectorenergydemandincreasessubstantiallyineachscenario,risingfrom35%todayto40%intheSTEPS,43%intheAPS,and48%intheChapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix119NZEScenarioby2030.IntheSTEPS,powersectordecarbonisationandtheuseofelectricityandrenewablesinplaceofcoalandoilleadstoadeclineinbuildingssectoremissions(includingindirectemissions5)of1.4gigatonnesofcarbondioxide(GtCO2)by2030despiterisingenergydemand,notablyforspacecooling.TheAPSreflectsadditionalpledgestoprovideaccesstocleancooking(seeChapter4,section4.4.1),withmodernbioenergymeetingmostofthisadditionalconsumption.BuildingssectoremissionsdeclinemorethantwiceasfastasintheSTEPSby2030.Figure3.11⊳Residentialfloorareabyenvelopetypeandenergyintensityofheatedandcooledfloorareabyscenario,2022-2050400STEPS401020APS120Billionm2kWh/m230030909020020606010010303020222030204020502022203020402050RetrofitEnvelopetype:Non-compliantCompliantZero-carbon-readyIEA.CCBY4.0.Energyintensity(rightaxis):HeatingCoolingImplementationofproposalstoimprovebuildingenvelopeslowersheatingandcoolingintensitiesby30%intheAPSrelativetotheSTEPSby2050Notes:m2=squaremetre;kWh/m2=kilowatt-hourpersquaremetre.Zero-carbon-readyenvelopesenableabuildingtobezero-carbonemissionswithoutfurtherrenovationoncethepowerandnaturalgasgridsthatitreliesonarefullydecarbonised.Heatedandcooledfloorspaceevolvesovertimewithchangesinclimateandintheownershipofheatingandcoolingtechnologies.Akeydifferencebetweenthescenariosisthelevelofambitionforimprovingbuildingdesigns(Figure3.11).IntheSTEPS,around45%ofthebuildingstockisconstructedorretrofittedincompliancewithbuildingenergycodesorzero-carbon-readystandardsby2050.IntheAPS,thisshareexceeds65%,accountingforincreasedpolicyambitionincludingtheproposedupdatetotheEUEnergyPerformanceofBuildingsDirective,proposednewstandardsforfederalbuildingsintheUnitedStates,andChina’sCarbonPeakingandNeutralityBlueprintforUrbanisationandRuralDevelopment.Whiletheenergysavingsgainedfromcompliancewithbuildingenergycodesvarydependingonthestringencyofthecodes,zero-carbon-readystandardsmorethanhalveheatingandcoolingdemandcomparedwiththeaveragestocktoday.Policyincentivescounterbalancebarrierstoimprovingbuildingenvelopes,includingIEA.CCBY4.0.5Indirectemissionsarefromtheelectricityandheatgenerationneededtomeetdemandinbuildings.120InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023thecostofmaterialsandthesplitincentivesfacedbypropertyownersandtenants(IEA,2023a).Comparedtobuildingsconstructedoverthelastdecade,thoseconstructedinthe2030sareonaverage15%moreefficientintheSTEPSand36%moreefficientintheAPS.IntheNZEScenario,theyare66%moreefficient,withallnewbuildingsfrom2030onwardsbeingzero-carbon-readyandalargershareofexistingbuildingsundergoingretrofits.Table3.3⊳KeyenergydemandpoliciesforbuildingsbyregionMandatoryIncentivesMinimumenergy3buildingperformancestandardsenergycodesRetrofitsHeatpumpsCoolingAppliancesUnitedStates◕●●●●LatinAmericaand◔◔○◕◕theCaribbeanEuropeanUnion●●◕●●Africa◔○○◔◔MiddleEast◑◑◑◑◕Eurasia◑◔○◔●China●◑◑●●India◕○○○●JapanandKorea●●●●●SoutheastAsia◑◔○◑◑Shareofcountriesorjurisdictionswithineachregionwithpolicycurrentlyimplemented:○<10%◔10-39%◑40-69%◕70-99%●100%Notes:Inregionswithonecountry,unlessthereisanationalpolicyinplace,sharesareshownforsubnationaljurisdictions.Somepolicytypesarenotequallyrelevantforallregionsgivenvariationsinheatingandcoolingneedsandtheageofthebuildingstock.IEA.CCBY4.0.Deployingmoreenergy-efficienttechnologiesisanotherkeyfactordifferentiatingenergydemandandemissionsinthebuildingssectorinourscenarios.Installedcapacityofheatpumpsinbuildingsisaround15%higherintheAPSthanintheSTEPSby2030,whileunitelectricityconsumptionofappliancesdecreasesbyover10%overthesameperiodcomparedwitharound5%intheSTEPS,partlybecauseofmoreeffectiveMEPS.Theyareaprimarypolicytoolforimprovingtechnologyefficiencyandareimplementedrelativelyconsistentlyacrossregionscomparedtoothertypesofpoliciesrelatedtothebuildingssector(Table3.3).Nevertheless,thereisscopeforthemtobemorewidelyadopted,andformorestringentstandardsandenforcement.Second-handmarketsforappliancesposeaparticularbarriertofurtherefficiencygains,especiallywithrapidgrowthintheownershipofappliancesandairconditionersindevelopingeconomies.IntheNZEScenario,light-emittingdiodes(LEDs)makeup100%oflightingsalesby2030andbestavailabletechnologiesmakeupthemajorityofapplianceandcoolingequipmentsalesby2035.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix121Whatwillittaketodecarboniseheatinginbuildings?Heating–spaceandwaterheating–accountsforaround45%ofenergydemandand80%ofdirectCO2emissionsfrombuildings.IntheSTEPS,theshareofenergyservicedemandforheatingmetbyfossilfuelsis50%by2030and35%by2050,andheatingstillreleasesemissionsof1.5GtCO2eachyearby2050(Figure3.12).IntheNZEScenario,bycontrast,heatingisentirelydecarbonisedthroughaswitchtoelectricity,renewablesanddistrictheatandthroughefficiencygainsviaenvelopeandtechnologyimprovements.ElectrificationintheNZEScenarioreliesstronglyontheuptakeofheatpumps,whichhaveseenrapidexpansioninrecentyears(section3.6).Figure3.12⊳Shareofglobalenergyservicedemandforheatinginbuildingsbyfuelandscenario,2010-205075%STEPSAPSNZE50%25%201020502010205020102050FossilfuelsElectricityRenewablesDistrictheatingIEA.CCBY4.0.Fuelswitchingiscriticaltodecarboniseheating,includingthroughthephase-outoffossilfuelboilersandtheuptakeofheatpumpsandotherlow-emissionsoptionsIEA.CCBY4.0.Policiesthatsupportthedecarbonisationofheatingincludebuildingenergycodes,heatingintensitystandards,carbonpricing,incentivestoadoptheatpumpsandcleantechnologiesandbansonthesaleofnewfossilfuelequipment.Todate,13Europeancountrieshaveimplementedorannouncednationalbansorothernationalpoliciestolimittheinstallationofoil-firedboilers,ofwhichninehavedonethesameforgas-firedboilers.Sub-nationaljurisdictionswithinAustralia,Canada,ChinaandUnitedStates,amongothercountries,haveannouncedsimilarmeasures.IntheAPS,theimplementationofbansonfossilfuelboilersorfurnacesthathavebeenannouncedtodatereducesheatingdirectemissionsby420milliontonnesofcarbondioxide(MtCO2)by2050.Whilebansonfossilfuelboilersareonlyoneexampleofmanypolicysolutionsthatcandecarboniseenergyuseforheatinginbuildings,theycanbeusefultoprovideclearmarketsignalstostakeholdersandtoalignincentivesforpropertyownersandrenters.IntheNZEScenario,bansonfossilfuelboilersareappliedineveryregionfrom2025onwards,resultingincumulativeemissionssavingsof19GtCO2fromtodayto2050.122InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Althoughhighupfrontcostspresentadeterrenttomanyhouseholds,switchingtonon-fossilfueloptionscanreducehouseholdspendingonheatingovertime(IEA,2022b).Whilefossilfuelboilersandfurnaceshavelowerupfrontcostsinmostmarkets,heatpumpstypicallyhaveloweroperatingcostsduetotheirhighefficiency.IEAanalysisoflifecyclecostsbyheatingtechnology(basedonaveragenon-subsidisedtechnologypricesandrelyingonend-userfuelpriceprojectionsconsistentwiththeSTEPS)findsoil-firedboilerstooftenbethemostexpensiveoption.Heatpumpandgas-firedboilerlifecyclecostsaremorecomparable,withcostdifferencesdependingchieflyonfuelandCO2pricesandongasandelectricity3networkcosts.Indenselypopulatedareas,wheretheinstallationofheatpumpscanprovedifficultinsomebuildings,districtheatingcanprovideaviablelow-emissionsalternative.3.4ElectricityOverviewGlobalelectricitydemandissettoincreaserapidlyinallscenariosasaresultofpopulationandincomegrowthandtheelectrificationofincreasingnumbersofend-uses.By2050,demandforelectricityrisesfromitscurrentlevelbyover80%intheSTEPS,120%intheAPSand150%intheNZEScenario(Figure3.13).Theadditionaldemandismetmainlybylow-emissionssourcesofelectricity–renewables,nuclearpower,fossilfuelsequippedwithcarboncapture,hydrogenandammonia–raisingtheirshareofelectricitysupplyineachscenario.Theshareofunabatedfossilfuelsdeclinessharply,withtheircombinedoutputfallingbyoverone-thirdfrom2022to2050intheSTEPS,three-quartersintheAPSandnearly100%intheNZEScenario.Figure3.13⊳Globalelectricitydemand,2010-2050,andgenerationmixbyscenario,2022and2050ElectricitydemandElectricitygenerationThousandTWh80100%OilUnabatednaturalgas6075%UnabatedcoalFossilfuelswithCCUSHydrogenandammonia4050%NuclearOtherrenewablesHydro2025%OffshorewindOnshorewindSolarPV20102020203020402050STEPSAPSNZESTEPSAPSNZE20222050IEA.CCBY4.0.Electricitydemandrisesover80%tomorethan150%by2050acrossscenariosandismetincreasinglybylow-emissionssourcesattheexpenseofunabatedcoalandnaturalgasIEA.CCBY4.0.Notes:TWh=terawatt-hours.Otherrenewablesincludebioenergyandrenewablewaste,geothermal,concentratingsolarpowerandmarinepower.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix123ElectricitydemandGlobalelectricitydemandgrowthto2050isdrivenbyemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,whichtogetheraccountforaboutthree-quartersoftheglobaltotalintheSTEPS,APSandNZEScenario.Today,Chinaisthelargestelectricityconsumeranddemandgrowthofover2%onaverageperyearto2050inallscenariosmeansthatitusestwiceormoreasmuchelectricityasanyothercountryby2050.Annualelectricitydemandgrowthofaround5%putsIndiabehindonlyChinaandtheUnitedStatesintermsofelectricityconsumptionby2050inallscenarios.Otheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesalsoseerobustelectricitydemandgrowthstemmingfromincreasingpopulations,economicdevelopmentandrisingincomes.Inadvancedeconomiesasagroup,electricitydemandgrowthislower,rangingbetween1.4%peryearintheSTEPSto2.4%intheNZEScenario.Globalelectricitydemandrisesinallsectorsandinallscenarios.Thebuildingssectorremainsthelargestintermsofconsumptionthroughto2050intheSTEPSandAPSasdemandcontinuestoriseforappliances,spacecoolingandheatingandwaterheating,thoughenhancedenergyefficiencytempersgrowthintheNZEScenario(Figure3.14).Theindustrysectorcontinuestobethesecond-largestuserofelectricityintheSTEPSandAPS,withelectricmotorsaccountingformuchofitsdemand,butbecomesthelargestintheNZEScenario.EVsaccountforabout15%oftotalelectricitydemandgrowthto2050intheSTEPS,andahigherpercentageintheAPSandNZEScenario,whereEVsalesrisefasterandbecomeakeydriverofelectricitydemandgrowth.TheproductionofhydrogenviaelectrolysisremainslimitedintheSTEPSbutaddssignificantlytoelectricitydemandgrowthintheAPSandevenmoresointheNZEScenario.Figure3.14⊳Electricitydemandbysectorandregion,andbyscenarioBysectorByregionSectors80OtherThousandTWh60Hydrogen40Transport20IndustryBuildings2022STEPSRegionsAPSOtherAENZEEUSTEPSUSAPSAENZEOtherEMDE2022IndiaSTEPSChinaAPSEMDENZESTEPSAPSNZE2030205020302050IEA.CCBY4.0.Emergingeconomiesseerobustelectricitydemandgrowthreflectingpopulationgrowthandrisingincomes;EVsandhydrogenproductionaddtoelectricitydemandgrowthIEA.CCBY4.0.Note:EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies;AE=advancedeconomies;US=UnitedStates;EU=EuropeanUnion.124InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023ElectricitysupplyResponsestothecurrentenergycrisishaveemphasisedaddressingsecuritychallengeswhileacceleratingcleanenergytransitions,particularlyintheelectricitysector.Recentpolicydevelopmentshaveboostedtheprospectsforrenewablesinmajormarkets,includingChina,EuropeanUnion,India,JapanandUnitedStates(Table3.4).Prospectsfornuclearpowerhavealsoimprovedinleadingmarkets,withsupportforlifetimeextensionofexistingnuclearreactorsinanumberofcountriesincludingJapan,KoreaandUnitedStates,andsupportforsnteawtesre(aIEcAto,r2s02in3bC)a.nRaedcae,ntChpionlaic,yUdneivteedlopKminegndtosmh,avUenibteeednSmtaitxeesd,faonrdnasetuvrearlaglaEsUusmeeimnbtheer3powersector:EuropeanUnion,KoreaandJapanaretakingeffortstoreducedemandandrelianceonimports,whileChinaseesacontinuedrolefornaturalgas.Whilethecurrentglobalenergycrisishasledtoatemporaryuptickincoal-firedpowergeneration,countrieswithplanstophaseoutunabatedcoalremaincommitted.Table3.4⊳RecentmajordevelopmentsinelectricitysupplypoliciesandtheircombinedimpactontheoutlookforselectedregionsCombinedimpactonoutlookfor:RegionMajorpolicyRenewablesNuclearUnabatedUnabatednaturalgascoalChinaIndia14thFive-yearPlanandupdatedNationallyDeterminedContributionEuropeanUnionRevisedNationallyDeterminedUnitedContributionaimingfor50%non-fossilStatespowergenerationcapacityby2030CanadaKoreaRenewableEnergyDirectiveIII(42.5%Japanofgrossfinalconsumptionin2030),includingnuclear-basedhydrogenInflationReductionActwithUSD370billionforcleanenergytechnologiesInvestmentTaxCreditsforelectricity,hydrogen,CCUSandmanufacturing10thBasicPlanforLong-termElectricitySupplyandDemand6thStrategicEnergyPlanandGreenTransformation(GX)policyinitiativeFavourableUnfavourableNeutralIEA.CCBY4.0.Thegrowthofelectricitygenerationfromlow-emissionssourcesacceleratesinallthreescenarios,withtheircombinedoutputquadruplingfrom2022to2050intheSTEPS,growingto5.5-timesitscurrentlevelintheAPS,andincreasingsevenfoldintheNZEScenario(Figure3.15).Asaresult,theglobalshareofelectricitygenerationfromlow-emissionssourcesfrom39%in2022risesby2050toabout80%intheSTEPS,over90%intheAPS,andnearly100%intheNZEScenario.Thisenablesadvancedeconomiesandemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesaliketoreducetheirrelianceonfossilfuels.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix125Figure3.15⊳Globalelectricitygenerationbysourceandscenario,1990-205080STEPSAPSNZEThousandTWh6040201990202220502022205020222050WindSolarPVNuclearHydroUnabatednaturalgasOtherrenewablesOtherlow-emissionsUnabatedcoalOtherIEA.CCBY4.0.Renewablesoutpaceelectricitydemandgrowthto2030intheSTEPS,leadingtoapeakincoal-firedpowerintheneartermthoughannouncedpledgescallforfasterdeclinesNotes:TWh=terawatt-hours.Otherlow-emissionsincludefossilfuelswithCCUS,hydrogenandammonia.IEA.CCBY4.0.Renewablesprovided30%ofelectricitygeneratedworldwidein2022,andthisrisestonearly50%by2030intheSTEPS.Hydropoweristhelargestlow-emissionssourceofelectricitytoday,accountingfor15%ofgeneration,butitsannualoutputcanvarywidely,andhighupfrontcapitalcostsandlimitationsondevelopmentoffavourablesitesconstrainfurthergrowthprospects.Otherrenewables–bioenergy,geothermal,concentratingsolarandmarinepower–haveaparttoplaytoo,butsolarPVandwindarethecentraltechnologiesintheroll-outofrenewablestodecarboniseenergysupplyfaster.Renewablescapacityexpands2.4-foldintheSTEPSby2030,2.7-foldintheAPSandtriplesintheNZEScenario,andalmost95%ofthisgrowthisintheformofsolarPVandwind(Figure3.16).TheshareofwindandsolarPVintotalgenerationissettorisefrom12%toabout30%by2030,puttingpowersystemflexibilityattheheartofelectricitysecurity(seeChapter4)andunderliningtheneedtospeeduppermittingandgridexpansion(IEA,2023a).Nuclearpoweristhesecond-largestsourceoflow-emissionspowerworldwidetoday,behindhydropowerbutfarlargerthanwindorsolarPV.Inadvancedeconomies,nuclearpoweristhelargestsourceoflow-emissionselectricity.AfteradecadeofslowdeploymentinthewakeoftheaccidentattheFukushimaDaiichiNuclearPowerStationinJapan,achangingpolicylandscapeiscreatingopportunitiesforanuclearcomeback(IEA,2022c).Nuclearpowercapacityincreasesfrom417GWin2022to620GWin2050intheSTEPS,withgrowthmainlyinChinaandotheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,whileadvancedeconomiescarryoutwidespreadlifetimeextensionsandlooktobuildnewprojectstooffsetretirements.Large-scalereactorsremainthedominantformofnuclearpowerinallscenarios,includingadvancedreactordesigns,butthedevelopmentofandgrowinginterestinsmallmodularreactorsincreasesthepotentialfornuclearpowerinthelongrun(NEA,126InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20232022).MorelifetimeextensionsandnewconstructionincountriesopentonuclearpowerboostglobalcapacityintheAPSto770GWin2050,andtowellover900GWintheNZEScenario,wherenuclearconstructionreachesnewheights(IEA,2023a).Figure3.16⊳Globalinstalledpowercapacitybyselectedtechnologyandscenario,2022-205020STEPSAPSNZEThousandGW315105202220502022205020222050SolarPVWindHydroOtherrenewablesNuclearUnabatedcoalUnabatednaturalgasBatterystorageIEA.CCBY4.0.SolarPVcapacitytakesoffinallscenarios,withonlywindpoweratthesamescaleinthelongterm;theirvariablenatureleadstoincreaseddeploymentofbatterystorageIEA.CCBY4.0.Coalisthelargestsourceofelectricityintheworldtoday,accountingfor36%ofthetotal,butisovertakenbyrenewablesby2025inallthreescenarios.By2030,withnewconstructionslowingandeffortstotransitionawayfromcoalunderwayinmanycountries(IEA,2022d),theshareofunabatedcoalinelectricitygenerationfallsbelow25%intheSTEPS,20%intheAPSand15%intheNZEScenario.InSTEPS,unabatedcoal-firedpowerpeaksinChinaaround2025andshortlyafter2030inIndia.Beyond2030,theuseofunabatedcoalinpowercontinuestodiminishasthelargestusers–China,India,Indonesiaandotheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies–increasinglylooktoalternatives.Theroleofnaturalgasinpowersystemsisevolvingandvarieswidelybyscenario.Today,naturalgasprovides22%ofglobalelectricityaswellasflexibilityandreliabilityservices,butgas-firedgenerationpeaksbefore2030inallthreescenarios.Itsshareintotalelectricitygenerationfallstounder20%in2030andcloseto10%by2050intheSTEPS,withmarketsinadvancedeconomiesincreasinglylookingtogas-firedpowerplantsforflexibilityratherthanbulkoutputastheyintegraterisingsharesofsolarPVandwind.Whilegas-firedpowerrisesinabsolutetermsinChinaandotheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesbeyond2030,itssharegraduallydeclines.IntheAPS,transitionshappenmorequickly,leadingtounabatednaturalgas-firedgenerationfallingbyhalffrom2022to2050,andtoanearcompletephaseoutintheNZEScenarioby2050.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix127Coal-andgas-firedpowerplantsequippedwithCCUSandthoseco-firingwithhydrogenandammoniacontributetolow-emissionspowermainlyafter2030.LimitedprogressismadeintheSTEPS,butthepacepicksupintheAPSandtheNZEScenario.Theyprovideover1500TWhofelectricitygenerationby2050intheAPS,risingtomorethan2100TWhintheNZEScenario,whichisequivalenttoallglobalwindgenerationtoday.Alongwithrepurposingtofocusonflexibilityandretiringplantsearly,retrofittingexistingcoalplantstoco-fireammoniaofferssignificantopportunitiestocutemissionswhilecontinuingoperations(IEA,2022d).PowersectorCO2emissionsGlobalpowersectorCO2emissionswerecloseto15gigatonnes(Gt)in2022(includingbothelectricityandheatproduction),accountingforalmost40%ofallenergy-relatedCO2emissions.Powersectoremissionsaresettopeakintheneartermandthenstartdeclininginallscenarios.Weatherconditionsinmajormarketswillinfluencetheprecisetiming,forexampledroughtscouldlowerhydropoweroutputandtemporarilyraisetheuseoffossilfuels.By2030,globalpowersectoremissionsaredownabout15%intheSTEPS,30%intheAPSand45%intheNZEScenario,whichseeselectricitysectoremissionssubsequentlyfalltonetzeroby2035inadvancedeconomiesinaggregate,2040inChinaandjustbefore2045globally(Figure3.17).Thismakesthepowersectorthefirsttoreachnetzeroemissions.Figure3.17⊳Globalpowersectoremissions,2010-2050,andCO2intensityofelectricitygenerationbyregionandscenario,2022and2030GlobalpowersectorCO₂emissionsCO₂intensityofelectricitygeneration16800EMDE1284GtCO₂AEgCO₂/kWh600ChinaUnitedStates400EuropeanUnionIndia200Annualemissions1GtCO2201020202030204020502022STEPSAPSNZE2030-4STEPSAPSNZEIEA.CCBY4.0.Globalpowersectoremissionspeakintheneartermandthendeclinebyabout15%intheSTEPSand30%intheAPSby2030;theyfallfasterinallregionsintheNZEScenarioIEA.CCBY4.0.Notes:GtCO2=gigatonnesofcarbondioxide;gCO2/kWh=grammesofcarbondioxideperkilowatt-hour;EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies;AE=advancedeconomies.IntheNZEScenario,emissionsfromfossilfuelcombustionarecounterbalancedbycarbondioxideremovalthroughbioenergywithcarboncaptureandstorage.128InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023PowersectorinvestmentTotalpowersectorinvestmentincreasesinallscenariostomeetelectricitydemandgrowth,supportcleanenergytransitionsandmaintainelectricitysecurity.SolarPVandwindcurrentlyaccountformoreinvestmentthanelectricitygrids,butprojectedcostreductionsforsolarPVandwindmoderatefutureinvestmentneedsatthesametimeasgridinvestmentneedsrise(Figure3.18).Gridinvestmentiskeytoconnectmillionsofnewcustomersandnewrenewablesources,reinforcetransmissionanddistribution,andmoderniseanddigitalisesystems(IEA,2023c).Batterystorageattractsincreasinginvestmenttoprovide3hour-to-hourflexibilityandgridstability,whileinvestmentinunabatedfossilfuelpowerplants,alreadylowinrecentyears,dropstoaminimallevelandismostlyfocussedonnaturalgas-firedpowerfortheprovisionofflexibilityservices.IntheSTEPS,globalpowersectorinvestmentrisesfromUSD1.0trilliononaverageover2018-2022toUSD1.4trillionby2030andmaintainsthatlevelthroughto2050.IntheAPS,powersectorinvestmentrisestoUSD1.8trillionby2030;intheNZEScenario,itincreasesfurthertoUSD2.2trillion.Figure3.18⊳Averageannualglobalinvestmentinthepowersectorbytypeandscenario,2018-2022and2030BillionUSD(2022,MER)1000Low-emissions750Wind5002018-22SolarPV250STEPSOtherlow-emissionsAPSNuclear2030NZEOtherrenewablesHydro2018-22STEPSElectricitygridsandstorageAPSBatterystorageNZET&Dgrids2018-22UnabatedfossilfuelsandotherSTEPSOtherAPSUnabatednaturalgasNZEUnabatedcoal2018-22IEA.CCBY4.0.STEPSAPSNZE203020302030Powersectorinvestmentrisesby50%to2030intheSTEPS,90%intheAPS,mainlyduetohigherspendingonsolarPV,wind,gridsandstorage,buttheNZEScenariocallsformoreNotes:MER=marketexchangerate;T&D=transmissionanddistribution.Otherlow-emissionsincludefossilfuelswithCCUS,hydrogenandammonia.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix1293.5Fuels3.5.1OilTable3.5⊳Globalliquidsdemandandsupplybyscenario(mb/d)STEPSAPSNZE2010202220302050203020502030205036.5Roadtransport41.341.135.537.615.929.11.6Aviationandshipping9.9Industry17.210.613.517.212.59.010.52.1Buildingsandpower12.4Othersectors11.120.623.325.521.417.820.314.3Worldoildemand87.1Liquidbiofuels11.49.56.78.64.16.10.5Low-emissionshydrogen-basedfuels1.2Worldliquidsdemand-12.614.012.512.47.911.45.7ConventionalcrudeoilTightoil88.496.5101.597.492.554.877.524.3Naturalgasliquids67.4Extra-heavyoilandbitumen2.23.04.54.86.95.65.3Otherproduction0.7Worldoilproduction12.7-0.00.20.23.60.76.0OPECshareWorldprocessinggains2.098.7104.5102.197.565.383.735.5Worldoilsupply0.5IEAcrudeoilprice(USD[2022]/barrel)83.162.861.358.254.929.848.015.840%2.28.311.110.210.36.97.61.885.310319.021.219.420.113.616.24.43.74.45.53.92.53.01.50.91.01.20.90.30.30.094.899.194.590.253.175.123.536%35%43%35%45%37%53%2.32.42.92.41.62.30.797.1101.597.492.554.877.524.398828074604225Notes:mb/d=millionbarrelsperday;OPEC=OrganizationofthePetroleumExportingCountries.Otherproductionincludescoal‐to‐liquids,gas‐to‐liquids,additivesandkerogenoil.Historicalsupplyanddemandvolumesdifferduetochangesinstocks.Liquidbiofuelsandlow-emissionshydrogen-basedliquidfuelsareexpressedinenergyequivalentvolumesofgasolineanddiesel,reportedinmillionbarrelsofoilequivalentperday.SeeAnnexCfordefinitions.IEA.CCBY4.0.GlobaloilmarketshavebeenreshapedbytheturbulencecausedbytheCovid-19pandemicandRussia’sinvasionofUkraine.Overalloildemandin2022remainedslightlybelow2019levels:oiluseasapetrochemicalfeedstockin2022wasaround1mb/dhigher,butthiswasmorethanoffsetbylowerlevelsofuseinroadtransport(1mb/dlower)andaviation(2mb/dlower).Demandcontinuedtoincreasein2023andreachedanewmonthlyrecordinJune.Onthesupplyside,cutsinproductionbytheOPEC+grouping,whichincludesRussiaandotherexporters,inthefirst-halfof2023werelargelyoffsetbyhigheroutputelsewhere.Non-OPEC+increasesinsupplyareexpectedtobelimitedduringtherestof2023despitefurthercutsbyOPEC+inJulyandAugust.ThereareanumberofchangesindemandandsupplytrendsfromtheWEO-2022.OildemandreachesitsmaximumlevelinthisOutlook’sSTEPSaroundfiveyearsearlierthanintheWEO-2022andtotaldemandin2050isaround5mb/dlower.ThisstemsmainlyfromfasterprojectedincreaseinEVsalesinthisOutlookinthelightofadditionalpolicysupport130InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023aswellasplanstoestablishEVmanufacturinghubsinanumberofemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Onthesupplyside,thefallinproductionfromRussiaislessimmediatethanprojectedintheWEO-2022,butthelong-termdeclineremainssimilar.ProductionbymembersofOPECandbycountriesinLatinAmericaandtheCaribbeanin2050isaround2mb/dlowerineachthanprojectedintheWEO-2022,andproductioninNorthAmericaisaround1mb/dlower.InthisOutlook,oilpricesremainflatintheSTEPSataroundUSD80/barrel,whereastheygraduallyfalltoUSD60/barrelby2050intheAPS(Figure3.19).ItnotUhSeDN4Z0E/Sbcaernrealriino,2t0h3e0parnicdetgrreandduinalglylofawllesrttohtehreeamftaerrg.inalcostofoilproduction,dropping3Figure3.19⊳Globaloildemandandcrudeoilpricebyscenario,2000-2050OildemandOilprice125150mb/dUSD/barrel100120759050602530200020102020203020402050200020102020203020402050STEPSAPSNZEIEA.CCBY4.0.Oildemandandpricespeakinthelate-2020sintheSTEPS;therearemuchsharperdeclinesinboththeAPSandNZEScenarioIEA.CCBY4.0.DemandIntheSTEPS,oildemandreachesitsmaximumlevelof102mb/dinthelate2020sbeforedecliningslightlyto97mb/din2050,withreduceddemandinroadtransportasaresultoftheriseofEVsoffsetbyincreasedoiluseinpetrochemicalsandinaviation.Inpractice,thiswouldprobablymeananundulatingplateaulastingformanyyearswithdemandmovingslightlyaboveandbelowalong-termaveragefromyeartoyear.IntheAPS,thereisamuchmorepronounceddeclineindemand,whichfallsto93mb/din2030andto55mb/din2050.Oildemandinroadtransportmodesfallsmoresharply,withEVsaccountingformorethan75%ofpassengercarandtrucksalesin2050.Onlyinpetrochemicalsandaviationismoreoilusedin2050thanin2022.Thereareplanstorestrictorbantheproductionandutilisationofsingle-useplasticsandtoscaleupplasticsrecycling,butthesedonotpreventanoverallincreaseinglobaldemandforplastics.Theuseofsustainableaviationfuelsincreases,butoiluseforaviationneverthelessgrowstotheChapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix131mid‑2030sandthenonlydeclinesslowly.Maritimeoilusefallsby55%between2022and2050,however,andhalfofthefuelsusedinshipsin2050arelow-emissionsfuels.6IntheNZEScenario,oildemandfallsto77mb/din2030.Theelectrificationofcarsandtrucksmakesabiggercontributionthananythingelsetoreduceoiluse,butefficiencyimprovementsandlow-emissionsfuelsalsoplayanimportantrole,especiallyinaviationandshipping.Oildemandfallstojustunder25mb/din2050:around70%ofthisisaccountedforbytheuseofoilasapetrochemicalfeedstockandinproductssuchasparaffinwaxes,asphaltandbitumenwheretheoilisnotcombusted.Acrossthethreescenarios,thereisamuchwidervariationinthedemandoutlookinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesthaninadvancedeconomies.Oildemandinadvancedeconomiesdeclinesbybetween35-85%throughto2050;inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,itrangesfroma20%increasetoa70%decreaseoverthisperiod.Figure3.20⊳Globaloildemandbysectorandscenario,2000-2050STEPSAPSNZEmb/d1209060302000202220502022205020222050CarsTrucksAviationShippingBuildingsPowerFeedstockOtherindustryOtherIEA.CCBY4.0.DemandintheSTEPSpeaksby2030;increasesinaviationandpetrochemicalsmostlyoffsetdeclineselsewherethroughto2050;demanddeclinesrapidlyintheAPSandNZEScenarioProductionIntheSTEPS,UStightoilproductionin2022stoodatjustover7.5mb/danditincreasesbyaround2mb/dto2030;productionpeakssoonthereafterandfallsbacktoaround8.5mb/din2050.TherearealsomajorcontributionstothesupplymixfromBrazilandGuyana,withGuyanaincreasingproductiontoamaximumlevelofaround2mb/dinthemid-2030sbeforeitdeclinesslightly.ProductioninRussiadeclinesby3.5mb/dbetween2022and2050asitstrugglestomaintainoutputfromexistingfieldsortodeveloplargenewones.TotalIEA.CCBY4.0.6InJuly2023,theInternationalMaritimeOrganizationadoptedaversionofitsgreenhousegasemissionsstrategythatlookstoachievenetzeroemissionsfrominternationalshippingby2050,however,enforcementmechanismshaveyettobedecided.ThisstrategyisnotincludedintheAPS.132InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023productionbymembersofOPECincreasesbyamodest1mb/dto2030,givenaround1.5mb/dofdeclinesfromOPECproducersinAfrica.OPECandRussia’scombinedshareofglobaloilsupplyremainsbetween45-48%to2030butitrisesabove50%by2050asSaudiArabiaincreasesproduction.Wealsoassumethatbythenthereisagradualnormalisationoftheinternationalsituationincountriessubjecttosanctions,notablyIranandVenezuela,andproductionfromthesecountriesrises.IntheAPS,oildemanddeclinesby0.5%eachyearto2030,butexistingsourcesofsupplyfallatafasterrate,whichmeansthatnewconventionalcrudeoilprojectsareneeded3(Figure3.21).Guyanaisoneofthefewcountriestoseeanincreaseinproductionofmorethan1mb/dto2030.ThereiscontinueddrillingfortightoilintheUnitedStates,butproductionpeaksbefore2030andisaround1.5mb/dlowerin2050than2022levels.Figure3.21⊳OilproductionbyOPECandRussiaandothernon-OPECproducersbyscenario,2010-2050OPECandRussiaNon-OPECexcludingRussia60mb/d5040302010Declinewithnofutherinvestment2010202020302040205020102020203020402050InvestmentinexistingInvestmentinnewSTEPSAPSNZEIEA.CCBY4.0.NewoilprojectsareneededintheSTEPSandAPS,butnotintheNZEScenario;OPECandRussiatakealargershareofthemarketintheNZEScenarioIntheNZEScenario,oildemanddeclinesby2.5%eachyearonaverageto2030andcanbemetwithoutanynewconventionallongleadtimeoilprojects.Productionfallsacrossallregionsto2030.After2030,oildemandfallsbymorethan5.5%eachyear:thisissufficientlyrapidtocausetheclosureofanumberofhighercostprojectsbeforetheyhavereachedtheendoftheirtechnicallifetimes.IEA.CCBY4.0.Refining,tradeandinvestmentTherefiningindustryenjoyedbumperprofitsinrecentyearsasarecoveryindemandaftertheCovid-19pandemic,particularlyformiddledistillatessuchasdieselandkerosene,coincidedwiththefirstnetreductionincapacityin30years.TheindustryisnowsettoaddChapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix133morethan6mb/dofrefiningcapacity,mostlyindevelopingeconomiesinAsiaandtheMiddleEast:however,thiswaveofcapacityadditionsislikelytobethelast,withlimitedcapacitygrowthafter2030projectedinallscenarios.Transportfuelshavehistoricallybeenthemaincauseofdemandgrowthinrefiningoverthepastfewdecadesbutthisissettoend:in2050,theshareofgasolineintotaldemanddropsfrom25%todayto17%intheSTEPS,to14%intheAPS,andtoclosetozerointheNZEScenario.EmergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesinAsiacurrentlyaccountforjustover40%ofglobalcrudeoilimports.Morerobustdemandandlimiteddomesticproductionpotentialcausethissharetoriseto45-60%in2050inallscenarios.TheMiddleEastremainsthelargestcrudeoilexporterinallscenarios,butcrudeoilexportsfromNorthAmericaandLatinAmericaandtheCaribbeanrisefroma23%shareofthetotaltodayto30%intheSTEPSin2050and40%intheAPS.Russia’ssharemeanwhilecontinuestodecline.IntheNZEScenario,theMiddleEastplaysanoutsizedroleinservingglobalcrudeoilmarketsasalowcostproducer,withitsshareintotalexportsreaching65%by2050.Mostofthenewrefiningfacilitiescurrentlyunderdevelopmentareinproductexportingregions,whichmeanstheavailabilityofoilproductsonthemarketissettorise:thedeclineinproducttradeismuchmoremutedthantheoveralldeclineindemandintheAPSandtheNZEScenario.Figure3.22⊳Globaloilandnaturalgasinvestmentbyscenario,2022-2050STEPSAPSNZEBillionUSD(2022,MER)100075050025020222023e203020402050203020402050203020402050Upstream:existingfieldsRefiningGastransportUpstream:newfieldsOiltransportIEA.CCBY4.0.Oilandgasinvestmentisexpectedtoincreasein2023andtobesimilarto2030levelsintheSTEPS;itismuchhigherthanthelevelsneededintheAPSandNZEScenarioNotes:2023e=estimatedvaluesfor2023.NewfieldinvestmentintheNZEScenarioin2030isforprojectsthatarecurrentlyunderconstructionorthosethatareapprovedbeforetheendof2023.IEA.CCBY4.0.AtaroundUSD800billion,expectedoilandnaturalgasinvestmentlevelsin2023arebroadlyalignedwiththelevelneededintheSTEPSin2030,whichsuggeststhattheoilandgasindustrytodaydoesnotyetseeasignificantnear-termreductionindemandaslikely(Figure3.22).IntheAPS,investmentinnewandexistingfieldsisrequiredtoavoidsupply134InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023fallingfasterthandemand,buttheoveralllevelofinvestmentin2030fallstoaroundUSD630billion.IntheNZEScenario,investmentinexistingfieldsisneededtoensurethatsupplydoesnotdeclinefasterthandemand,butnonewconventionallongleadtimeoilandgasprojectsaredevelopedafter2023andinvestmentismuchlowerthantoday.Reductionsinfossilfuelinvestmentneedtobesequencedcarefullywiththescalingupofinvestmentincleanenergy.Investingmorethanisneededwhencleanenergyinvestmentisrampingupandefficiencymeasuresarereducingdemandwouldleadtolowerpricesandcouldalsorisklock-inoffossilfueluse.Conversely,reducingfossilfuelinvestmentinadvance3ofactionandinvestmenttoreducedemandwouldleadtomuchhigherandmorevolatilepricesduringenergytransitions.3.5.2NaturalgasTable3.6⊳Globalgasdemand,productionandtradebyscenarioSTEPSAPSNZE201020222030205020302050203020504159Naturalgasdemand(bcm)3326163842994173386124223403919Power13468611570140914367761435112871Industry6921509701061868654788325Buildings76119178698034155401638Transport1091571581256094615Low-emissionshydrogeninputs-413882736212713272871Other4181266678655597301482179ofwhichabatedwithCCUS7810327993359162512479Naturalgasproduction(bcm)327433142994173386124223403919Conventionalgas27695.12894301627421940236362732.3Unconventionalgas50413.7140511571119482104029315.9Naturalgasnettrade(bcm)64091992182737071918739LNG276261165658824250712128Pipeline364930926524612522047Naturalgasprice(USD/MBtu)UnitedStates5.84.04.33.22.22.42.04.34.1EuropeanUnion9.96.97.16.55.45.95.35.55.3Japan8.88.47.77.86.341417972321385China14.69.47.88.36.356129126283Low-emissionsgases(bcme)23893241971161Low-emissionshydrogen0239980809Biogas23428951117Biomethane12413666235IEA.CCBY4.0.Notes:bcm=billioncubicmetres;CCUS=carboncapture,utilisationandstorage;LNG=liquefiednaturalgas;MBtu=millionBritishthermalunits;bcme=billioncubicmetresequivalent(1bcmeofhydrogen=0.3milliontonnes).NettradereflectsvolumestradedbetweenregionsmodelledintheIEAGlobalEnergyandClimateModelandexcludesintra-regionaltrade.Otherincludesothernon-energyuse,agricultureandotherenergysector.Thedifferencebetweenproductionanddemandisduetostockchanges.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix135NaturalgasmarketshavebeenupendedbyRussia’sinvasionofUkraine.ThesharpreductioninpipelinesupplytoEuropetightenedglobalgasmarkets,resultinginrecordhighpricesandadropinglobaldemandbyaround1%in2022.Demandfellbyarecord13%inEurope,buttherewerealsorippleeffectsinemergingmarketsanddevelopingeconomiesinAsia,wheredemandinaggregatefellforthefirsttimeever.Majorgasproducingregionsshowedresilience,withoutputincreasingintheMiddleEastby3%andintheUnitedStatesby4%.Globaldemandremainedmutedinthefirsthalfof2023;China’srecoveryhasbeenuneven,whilearetreatfromrecordnaturalgaspricesinEuropesofarhasnotreinvigoratedgasconsumptionintheindustryorpowersectors.Thecrisispromptedascramblebygasimportingcountriesaroundtheworldtosecuresupplies.Thishasboostednear-termprospectsforadditionalinvestment,especiallyforliquefiednaturalgas(LNG)exportprojects.ButresponsestothecrisishavealsolaidthegroundworkforamorerapidshiftawayfromnaturalgasinEuropeandtheUnitedStates,whilemoreupbeatprojectionsforrenewablesimplyweakernaturalgasdemandgrowth,especiallyinemergingmarketsinAsia.DemandFigure3.23⊳Globalnaturalgasdemandbyscenario,2000-20505000STEPSAPSNZEbcm40003000200010002000202220502022205020222050BuildingsIndustryPowerHydrogenTransportOtherIEA.CCBY4.0.Eachscenarioprojectsanendtogrowthforgas;futureprospectsdependlargelyonthepaceandscaleofgrowthincleanpower,electrificationandefficiencyimprovements.IEA.CCBY4.0.IntheSTEPS,naturalgasdemandgrowthbetween2022and2030ismuchlowerthanthe2.2%averagerateofgrowthseenbetween2010and2021(Figure3.23).Itreachesapeakby2030,maintainingalongplateaubeforegraduallydecliningbyaround100bcmby2050.IntheAPS,demandpeaksevensooner,andis7%lowerby2030than2022levels.IntheNZEScenario,demandfallsbymorethan2%peryearfrom2022to2030,andbynearly8%peryearbetween2030and2040.Declineratesaremoderatedafter2040bythegrowinguseofnaturalgaswithCCUSfortheproductionoflow-emissionshydrogen.136InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Naturalgasdemanddeclinesinadvancedeconomiesinallscenarios.Robustsupportforcleanenergyreducestheshareofnaturalgasinenergysupplyby2030inthepowersectorandthenincreasinglyinbuildingsandindustry.Thereisacontinuedneedfornaturalgastobackupvariablerenewables,andthisisoftenhighlightedasareasonforitsenduringroleintransitions,butthisstandbyrolerequiresmuchlessconsumptionofnaturalgasthanoperatingplantsasbaseloadsupply;moreover,theroleofgasinensuringflexibilityovertimeiscomplementedbyotheroptionssuchasbatteriesanddemandresponse.By2050,lgeavsedl.eMmoanredrinapaiddvaenleccetdrifeiccaotnioonmioefshfaelalsttdoe1m2a0n0dbacnmdineftfhiceieSnTcEyPSg,ai4n0s%bbrienlgowgatshedocuwrnretnot3480bcmby2050intheAPSandto300bcmintheNZEScenario.Thereisawiderrangeofpossibleoutcomesfornaturalgasdemandinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies(Figure3.24).Majordifferencesemergeby2030,atatimewhenamplenewLNGsuppliesareanticipated,keepinggaspriceslowandpotentiallystimulatingrobustdemandgrowth.IntheAPSandNZEScenario,thispossibilityisprecludedbyrapidgrowthofrenewablesinthepowersector,whichstartstoreducethemarketshareofnaturalgasafter2030.Figure3.24⊳Naturalgasdemandbyregionandscenario,2010-2050AdvancedeconomiesEmergingmarketanddeveloping3000economiesSTEPSbcm2000APS1000STEPSAPSNZENZE2010202020302040205020102020203020402050UnitedStatesEuropeEurasiaMiddleEastChinaAsiaOtherRestofAsiaAfricaOtherIEA.CCBY4.0.Naturalgasdemanddeclinesinadvancedeconomiesineachscenario;inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesthedifferencebetweenscenariooutcomesislargerIEA.CCBY4.0.ProductionRussia’sinvasionofUkrainehaspromptedmajorgasproducerstobringnewsuppliestothemarket.In2022,upstreamspendingoutsideRussiashotupbymorethan15%,witharoundhalfofplannednewsupplylinkedtoexportprojects.IntheSTEPS,theMiddleEastemergesasthemainsourceofincrementalglobalsupply;itsglobalshareoftotalproductionofnaturalgasrisesfrom15%in2022to25%by2050.IntheAPS,MiddleEastproductionremainsresilientasthesoleregionproducingmoregasin2050Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix137thanin2022(Figure3.25).Therateofdeclineinotherregionsisdeterminedbythepipelinebcmofprojectsunderdevelopmentinthenearterm,theabilityofmajorproducerstofindexportoutletsinaworldwherenaturalgastradeisshrinking,andthecostofdevelopingnewsuppliesinthelongrun.Amongexportingregions,theUnitedStatesrecordsimpressivesupplygrowthto2030intheSTEPSwithanincreaseof90bcminshaleandtightgasproduction.OverthelongertermUSproductionfalls,contributingtoanoveralldeclineinproductioninNorthAmericaofnearly400bcmbetween2030and2050–primarilyduetodecliningdomesticdemand.ThelossofRussiangassupplytoEuropeandstagnantdemandleadstoa300bcmdropinEurasianproductionby2050.IntheNZEScenario,globalgasproductionfallssharplyinallregionsataratethatimpliesthatsomeprojectshavetoclosebeforereachingtheendoftheirtechnicallifetimes,thoughgrowinggasuseforhydrogenproductionslowsthedeclineafter2040inareaswherehydrogenisexported,notablytheMiddleEastandAustralia.Figure3.25⊳NaturalgasproductionbyregionintheStatedPoliciesandAnnouncedPledgesscenarios,2022-205015001200900600300NorthEurasiaMiddleAsiaAfricaEuropeC&SAmericaEastPacificSTEPSAPSAmerica20222022-2050:IEA.CCBY4.0.AglobalpeakingasdemandintheSTEPSleavesonlyahandfulofregionsproducingmorethantheydidin2022;productionintheAPSfallsacrosstheboard,ledbyNorthAmericaNote:C&SAmerica=CentralandSouthAmerica.IEA.CCBY4.0.TradeandinvestmentGlobalnaturalgastradeintheSTEPSincreasesnearly15%between2022and2030,whichishalftherateofgrowthduringthepreviousdecade,butmorethanfour-timeshigherthangrowthinoverallnaturalgasdemandto2030(Figure3.26).Two-thirdsofgloballytradednaturalgasisdeliveredasLNGintheSTEPSby2030,upfromalevelofaround50%in2021.TradeisalsorelativelyresilientintheAPSandNZEScenarioto2030:totalexportsin2030are20bcmabovetheir2022levelintheAPSand90bcmbelowitintheNZEScenario.138InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Figure3.26⊳ChangeinnaturalgassupplybalancebyregionintheStatedPoliciesandAnnouncedPledgesscenarios,2022-2030NetimportersChinaIndiaOtherDev.AsiaEuropeanUnionOtherNetexporters3MiddleEastNorthAmericaEurasiaAfricaOther-200-1000100200APS:DomesticsupplyNetexportsbcmSTEPS:DomesticsupplyNetexportsNetimportsNetimportsIEA.CCBY4.0.GlobalgastradeshowsresilienceinbothscenariosfortherestofthisdecadeNote:OtherDev.Asia=OthercountriesindevelopingAsia.IEA.CCBY4.0.TheUnitedStates,whichaccountsforover90%ofLNGexportprojectsapprovedsincethestartof2022,solidifiesitspositionastheworld’slargestgasexporterthroughto2030inallscenarios.AlthoughexportsalsoriseintheMiddleEast,notablyfromQatar,mostadditionalproductionintheregionto2030isneededtomeetdomesticdemand.Russiafailstoregainitspre-2022volumesoftotalgasexportsinanyofourscenarios.Theyfallanother20%by2030intheSTEPS,asrisingdeliveriestoChinathroughthePowerofSiberiapipelineandmodestgrowthinLNGexportsareoffsetbyfurtherdeclinesinpipelineexportstoEurope.IntheAPS,lowergasdemandgrowthinChinaandaglobalsurplusofLNGleavesRussiawithfewoptionstodiversifyintonon-Europeanmarkets:despitemodestincrementalgrowthinexportstoTürkiyeandCentralAsia,totalexportsfall25%by2030.Mozambiqueemergesasalargeexporterby2030,butAfrica’soverallgastradebalancefallsby2030intheSTEPSasLNGexportsfromWestAfricadeclineandahighershareofNorthAfricangasproductiongoestowardsmeetingdomesticdemand.IntheAPS,adearthofbuyerswillingtosignupfornew,longleadtimeexportprojectsmeansAfricanexportsfallone-thirdbelow2022levelsby2050.SincenaturalgasdemandpeaksinallWEOscenariosby2030,thereislittleheadroomremainingforeitherpipelineorLNGtradetogrowbeyondthen.Witharound650bcmofannualliquefactioncapacityinoperationandafurther250bcmunderconstruction,globalLNGmarketslookamplysuppliedintheSTEPSuntilatleast2040.IntheAPS,LNGdemandpeaksby2030andprojectsunderconstructiontodayaresufficienttomeetdemand.IntheNZEScenario,aglobalsupplyglutformsinthemid-2020sandunderconstructionprojectsarenolongernecessary.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix139IntheSTEPS,aroundUSD190billionisinvestedeachyeartodevelopupstreamgasbetween2022and2030,andafurtherUSD40billionisspenteachyearonLNGinfrastructure.IntheAPS,totalinvestmentspendingfallsto80%ofSTEPSlevelsby2030.IntheNZEScenario,upstreaminvestmentinnaturalgasislimitedtomaintainingsupplyatexistingprojectsandminimisingtheemissionsintensityofproduction.WhilethesponsorsofallLNGprojectscurrentlyunderconstructioncanexpecttofullyrecovertheirinitialcapitalinvestmentintheSTEPS,aroundtwo-thirdsoftheseprojectsareatriskofnotdoingsointheAPS,andupto75%couldfailtodosointheNZEScenario.InboththeAPSandNZEScenario,agooddealofgaswouldprobablyendupbeingsoldinanover-suppliedmarketatclosetoshort-runmarginalcosts,althoughthedegreeofexposuretovolumeandpriceriskbetweensuppliersandoff-takerswoulddependoncontractualarrangements.Someoperators,notablyinthecaseofpipelines,cantakecomfortfromprojectedspendingofUSD100billioneachyearonhydrogentransportinfrastructureintheNZEScenarioby2050:thiscouldprovidearouteforthemtodiversifyintolow-emissionsgases.3.5.3CoalTable3.7⊳Globalcoaldemand,productionandtradebyscenario(Mtce)STEPSAPSNZE2010202220302050203020502030205052185807Worldcoaldemand3108376950073465437715303257499Power16881614Industry3030179925788431852240Othersectors422424ofwhichabatedwithCCUS0%0%1642146314576471239234Advancedeconomies15851018Emergingmarketand3352033024116726developingeconomies363347890%1%0%25%3%81%Worldcoalproduction52356122Steamcoal406948885092453679526663CokingcoalPeatandlignite86698844983221397014352991436Advancedeconomies300246Emergingmarketand1512107550073465433715303257499developingeconomies3974266933881135372350472457397886691830350146105120457391006504685001996023819543572998383713312876404Worldcoaltrade9481164920831803417635129Tradeasshareofproduction18%19%18%24%19%27%19%26%CoastalChinasteamcoalprice153196877271565845Notes:Mtce=milliontonnesofcoalequivalent.CoastalChinasteamcoalpricereportedinUSD(2022)/tonneadjustedto6000kcal/kg.SeeAnnexCfordefinitions.IEA.CCBY4.0.TheaftermathofRussia’sinvasionofUkraineledtocoaldemandreachinganall-timehighin2022,andthatledtosoaringpricesandthedisruptionoftraditionaltradeflows.Record140InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023highcoalpricesandenergysecurityconcernsledtorenewedcoalinvestmentinChinaandIndia,wheredomesticproductionwasrampeduptoreducerelianceonimports,andinIndonesia,amajorsupplierofthesetwoeconomies.Elsewhere,countriesdidnotusemuchadditionalcoal,ornotforverylong:theincreaseindemandforcoalintheEuropeanUnionduetotheenergycrisisin2022wasequivalenttolessthanonedayofcoaldemandinChina.Manygovernments,banks,investors–aswellasminingcompanies–continuetoshowalackofappetiteforinvestmentincoal,particularlysteamcoal(whichismainlyusedinthepowersector).Unabatedcoalisprovingtobeadifficultfueltodislodgefromtheglobalenergymix.In3advancedeconomies,therearesignsthatitsshareisbeingstructurallyerodedbytherapidriseofrenewables,buttheoveralloutlookforcoaldependstoalargeextentondevelopmentsinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Chinaisespeciallyimportantinthiscontext,sinceitaccountsforatleasthalfofallcoaldemandthroughouttheOutlookperiodacrossallscenarios.Inthepowersector,coaltransitionsarecomplicatedbytherelativelyyoungageofcoalplantsacrossmuchoftheAsiaPacificregion:plantsindevelopingeconomiesinAsiaareonaveragelessthan15yearsold.DemandTheoutlookforcoalisheavilydependentonthestrengthoftheworld’sresolvetoaddressclimatechange(Figure3.27).IntheSTEPS,coaldemanddeclinesgradually.IntheAPS,itdrops25%belowcurrentlevelsby2030,and75%by2050;coaldemandpeaksinChinainthemid-2020sandinIndiainthelate2020s.IntheNZEScenario,globaldemandfallsbyaround45%by2030and90%by2050.Figure3.27⊳Changeincoaldemandbyregion,sectorandscenario,2022-502022-20302030-2050Mtce500Power0IndustryOther-500-1000-1500-2000-2500-3000IEA.CCBY4.0.STEPSAPSNZESTEPSAPSNZESTEPSAPSNZESTEPSAPSNZEAdvancedeconomiesEMDEAdvancedeconomiesEMDEIEA.CCBY4.0.CoaldemanddropssharplyintheNZEScenariofrom2022andintheAPSfrom2030,mostlyduetopledgesfromChinaandIndiatoachievenetzeroemissionsafter2050Notes:Mtce=milliontonnesofcoalequivalent;EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Otherincludesbuildings,agricultureandotherenergysector.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix141Inadvancedeconomies,coal-firedpowerplantsarerapidlyreplacedbyrenewablesandotherlow-emissionsalternativesinthepowersectorinallscenarios,andthereisacontinuedfocusonreplacingcoalintheindustrysector,wherenewtechnologiesandefficiencygainshelptoreducecoaldemandinsteelproductionandotherindustries.InChina,coalusealsofallsinallscenarios,withprogressspeedingupintheAPSfrom2030andintheNZEScenariofromnowonwards.InIndiaandotheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,theoutlookforcoalvariesmarkedlybetweenscenarios.IntheSTEPS,coaldemandincreasestothemid-2030sandthenmostlyplateaus,withreductionsinthepowersectorbeingoffsetbyhigherdemandfromtheindustrysector.IntheAPSandNZEScenario,patternsofcoaldemandaresimilartothoseseeninChina.ThereisverylimiteduseofCCUSwithcoalintheSTEPS.Around400milliontonnesofcoalequivalent(Mtce)ofcoaldemandin2050isequippedwithCCUSinboththeAPSandNZEScenario:thisequatestoaround25%ofdemandintheAPSandmorethan80%intheNZEScenario.Unabatedcoalusedropsbyover98%between2021and2050intheNZEScenario.ProductionGlobalcoalproductionroseabove6billiontonnesofcoalequivalentin2022,itshighestlevelever.EnergypricesandenergysecurityconcernsledChina,India,Indonesiaandothermajorcoalproducerstoexpanddomesticsupply,butthisincreaseinsupplymaybeshortlived(Figure3.28).Newminedevelopments,especiallythosewhichwouldproducesteamcoal,arefacingconcernsaboutfuturedemand,difficultiesaccessingfinanceandscrutinyonenvironmental,socialandgovernanceissues.Figure3.28⊳GlobalcoalsupplyandtypebyscenarioCoalsupplyCoaltypeMtce600050004000300020001000201020202030204020502022STEPSAPSNZESTEPSAPSNZESTEPS20302050APSNZESteamcoalCokingcoalLigniteandpeatIEA.CCBY4.0.Coalproductionfallsbynearly45%between2022and2050intheSTEPS,75%intheAPSandover90%intheNZEScenario;cokingcoalsupplydeclinesmuchlessthansteamcoalIEA.CCBY4.0.Note:Mtce=milliontonnesofcoalequivalent.142InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IntheSTEPS,globalcoalsupplyfallsgraduallyto2030,withincreasesinIndiaoffsetbyreductionsinadvancedeconomies,andthendropsbyabout30%from2030to2050.IntheAPS,supplydeclinesby30%to2030andby75%to2050,comparedto2022levels.Steamcoalfallsbyover3750Mtceby2050(75%reduction),whilecokingcoalfallsbylessthan650Mtce(65%reduction).ProductioninChinafallsby2680Mtce(80%reduction),accountingforcloseto60%oftheglobaldeclineinsupply.ProductioninIndiafallsby260Mtce(60%reduction).Theleadingexporters,AustraliaandIndonesia,seeproductionfcaolalblyparoroduunctdio8n5%deacnldin6e5s%bryes4p5e%ctitvoel2y0b3e0twaenedna20f2u2rtahnedr28055%0.bInetthweeNenZE2S0c3e0naarniod,g2l0o5b0a.l3Remainingproductionin2050isaround400Mtceofsteamcoaland100Mtceofcokingcoal.TradeTheAsiaPacificregionisthemaindriverofinternationalcoaltrade,accountingforaroundthree-quartersofglobalcoalimportsin2022(Figure3.29).Chinawasthelargestimporter(around230Mtce),whileAustraliaandIndonesiawerethetwomaincoalexporters,togetheraccountingfor60%ofcoalexportsin2022.Australiaaloneprovidedhalfofallcokingcoalexports.Figure3.29⊳Topcoalimportersandexportersbyscenario,2022,2030and2050ImportersExportersImportersChina20302022IndiaJapanSTEPSKoreaAPSEuropeNZEOtherimp.STEPSExportersAPS2050NZEAustralia-1200IndonesiaRussiaOtherexp.-60006001200MtceIEA.CCBY4.0.Coaltradediminishesinvolumebutincreasesasashareofproductionto2050inallscenariosNote:Otherimp.=otherimporters;Otherexp.=otherexporters;Mtce=milliontonnesofcoalequivalent.IEA.CCBY4.0.IntheSTEPS,Indiabecomestheworld’slargestcoalimporterinthelate2020s:itsimportsrisebyalmost10%to2030whileChina’sdecreasebynearly30%.In2050,Indiaimports25%morecoalthanin2022,mostofwhichiscokingcoal.ThischangesthedynamicsofexportingChapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix143economies:Australianexports,whicharearound50%cokingcoal,increaseby5%to2050,whileIndonesia,mainlyasteamcoalexporter,seesexportsfallby40%.IntheAPS,globalcoaltradefallsby30%to2030andby65%to2050comparedto2022.Around420Mtceofcoalisimportedin2050,mainlybycountrieswithlargedistancesbetweendomesticproductionandconsumptionhubsandwheredifferencesincoalqualityrequiredomesticproductiontobesupplementedwithimports.ImportsofcokingcoalinIndiaincreasebymorethan55%to2030asitexpandssteelproduction.Indonesianexportsdropbynearly35%to2030asthemarketforsteamcoalshrinks.AustraliaproducesahigherproportionofcokingcoalthanIndonesiaandinitiallyfaresbetter,withcoalexportsfallingby5%to2030,althoughitsexportssubsequentlyfallbyover45%between2030and2050.IntheNZEScenario,globalcoaltradedeclinesby90%between2022and2050ascleanenergytechnologiesprogressivelyandspeedilydisplacecoalacrosstheenergysystem.In2050,advancedeconomiesimportsmallquantitiesofcoalthatismostlyusedwithCCUStoproducesteelorsupplypowerduringdemandpeaks.InvestmentDespiterenewedinterestin2022,investmentincoalsupplyandcoal-firedpowerworldwidehasfallenaround15%since2015.MostnewprojectsinrecentyearshavebeeninChinaandIndia,whichtogetheraccountedforaround80%ofglobalinvestmentincoal-firedpowerplantsandsupplyin2022(Figure3.30).Figure3.30⊳Averageannualinvestmentincoalsupplyandcoal-firedpowergenerationbyregionandscenario,2010-205030020302050AdvancedeconomiesBillionUSD(2022,MER)250200OtherEMDE15010050China20102022STEPSAPSNZESTEPSAPSNZEIEA.CCBY4.0.Investmentincoalfallsineachscenariothisdecade:investmentin2030isabout50%lowerthanrecentyearsintheSTEPS,70%lowerintheAPSand80%lowerintheNZEScenarioIEA.CCBY4.0.Notes:EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Includesdemandfromcoal-firedpowerplantsequippedwithcarboncapture.144InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20233.5.4ModernbioenergyModernbioenergycomesinsolid,liquidandgaseousforms.Togetherthesefuelsmakeupmorethanhalfofglobalrenewablessupplytoday.Overallproductionincreased5%in2022toreach40EJ.Solidbioenergycurrentlyaccountsforthevastmajorityofproduction.Itismostlyderivedfromorganicwastesources,suchasforestryresiduesormunicipalsolidwaste,andoftenpelletisedforuseinpowergenerationorindustry,withasmallbutimportantshareusedin3thebuildingssector.IntheSTEPS,modernsolidbioenergyreaches44EJin2030and57EJin2050.IntheAPSandtheNZEScenario,productionrisestomorethan70EJby2050.Thisprovidesdispatchablerenewablepower,acost-competitivesourceofcleanheatforindustryandanalternativetothetraditionaluseofsolidbiomassinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Figure3.31⊳Globalbioenergysupplybytypeandscenario,2022-2050Liquids(mb/d)Solids(EJ)Gases(bcme)880600660450440300220150202220302050203020502030205020222030205020302050203020502022203020502030205020302050STEPSAPSNZESTEPSAPSNZESTEPSAPSNZEAdvancedBiomethaneConventionalTransformationBuildingsBiogasIndustryPowerIEA.CCBY4.0.Fullsustainablepotentialofbioenergyofaround100EJisfullyexploitedintheAPSandNZEScenario,withitsdifferentformsusedacrossthecleanenergyeconomyNote:mb/d=millionbarrelsperday;EJ=exajoules;bcme=billioncubicmetreequivalent.IEA.CCBY4.0.Liquidbiofuelsproductionincreasedbynearly5%in2022to2.1mb/d.IntheSTEPS,productionincreasesataround4%annually,reaching3mb/din2030and4mb/din2050.IntheAPS,itrisesfasterasliquidbiofuelsareincreasinglyusedtohelpmeetNationallyDeterminedContributionandnetzeroemissionstargets.IntheNZEScenario,liquidbiofuelsuseexpandsmorerapidlyto2030thanintheAPSbutthendecreasesbelowthelevelintheAPSby2050.ThereduceddemandforliquidbiofuelsintheNZEScenarioin2050comparedwiththeAPSisdrivenbyseveralfactors,includingfasteruptakeofEVs,morerapidefficiencyimprovementsinroadvehicles,shippingvesselsandairplanes,andreduceddemandforaviationduetobehaviourchange.Biogasandbiomethanearethesmallestpartofthebioenergysupplychain,butthereisgrowinginterestinbiomethaneinparticularasasourceoflow-emissionsdomesticgasChapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix145supply,especiallyinEurope.Worldwidearound300bcmofpotentialproductionfromagriculturalwastesandresidueslieswithin20kilometresofmajorgaspipelineinfrastructure,providingagoodmatchwithpossiblelarge-scaleproductionandinjectionintogasnetworks(Figure3.32).IntheSTEPS,combinedbiogasandbiomethaneproductionnearlydoublesby2030toreach80billioncubicmetresequivalent(bcme).Inallscenarios,theshareofbiomethaneintotalbiogasdemandincreases,driveninlargepartbythevalueattachedtoitsuseasadispatchablesourceofenergyanddrop-insubstitutefornaturalgas.IntheAPS,totalbiomethaneproductionreaches240bcmeby2050;intheNZEScenario,thisrisestonearly300bcme.Figure3.32⊳Assessedyearlybiomethanepotentialfromagriculturalwastesandresidues,andlocationofnaturalgastransmissionpipelinesMillionm3per100km2<0.50.5-1.01.0-1.51.5-2.02.0-2.52.5-3.0>3.0IEA.CCBY4.0.Around300bcmofbiomethanecouldbeproducedfromagriculturalwastes,upgradedtomeetpipelinequalitystandardsandsubsequentlyinjectedintonearbygaspipelinesSource:IEAanalysisbasedonGlobalEnergyMonitor(2022);UNFAO(2023).Totalmodernbioenergysupplyisaround65EJintheAPSby2030andover70EJintheNZEScenario(Figure3.31).By2050,thetotalsustainablepotentialassessedbytheIEAofaround100EJisfullyexploitedinboththeAPSandtheNZEScenario,withlargeincreasesintheuseoforganicwastesandshortrotationwoodycropsmorethanoffsettingadeclineintheuseofconventionalbioenergycropsandthetraditionaluseofsolidbiomass.Around10%oftotalbioenergyuseintheNZEScenarioisequippedwithbioenergycarboncaptureandstorage(BECCS)by2050,andthisplaysacriticalroleinoffsettingresidualemissions.Theshareofadvancedliquidbiofuelsintotalproductionrisesfrommorethan10%todayto55%in2050intheAPSandaround75%intheNZEScenario.Inallscenarios,maximisingtheuseofadvancedbiofuelshelpstoexpandbiofuelproductioninawaythathasminimalimpactonlanduse,foodandfeedprices.7IEA.CCBY4.0.7Advancedbiofuelsareproducedfromnon‐foodcropfeedstocks,whichcandeliversignificantlifecyclegreenhousegasemissionssavingscomparedwithfossilfuelalternativesanddonotdirectlycompetewithfoodandfeedcropsforagriculturallandorcauseadversesustainabilityimpacts.146InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20233.6KeycleanenergytechnologytrendsSolarPVandwindSolarPVandwindaresettodominatepowercapacityadditions.Globally,theyaccountforover70%oftotalcapacityadditionsbetweennowand2050inallWEOscenarios.Theydosobecausetheyarenowthecheapestnewsourcesofelectricityinmostmarkets,widelyavailableandenjoypolicysupportinover140countries.GlobalsolarPVcapacityadditions,includingbothrooftopsolarandutility-scaleprojects,3reachedarecordhighof220GWin2022,twicethelevelin2019andmorethanseven-timestheleveltenyearsearlier.IntheSTEPS,capacityadditionsriseto500GWin2030and580GWin2050:thisincludesreplacementsofsolarpanelsthattypicallylast20-30years(Figure3.33).IntheAPS,capacityadditionsrisefaster,reaching640GWin2030and770GWin2050.IntheNZEScenario,capacityadditionsreach820GWby2030andthesamelevelisachievedin2050.SolarPVonbuildings,includingrooftops,representsabouthalfoftotalsolarPVcapacityadditionstoday,andthismorethandoublesto2030inallthreescenarios.Off-gridsolarhomesystemsplayavitalroleinclosingelectricityaccessgapsinsub-SaharanAfrica,andtheiruseincreasestoo(seeChapter4,section4.4).However,utility-scaleprojectsmakeupthemajorityofnewsolarcapacityinallscenarios,inlargepartbecauseoftheirsignificantlylowerlevelisedcostsofelectricity.Figure3.33⊳SolarPVandwindcapacityadditionsbyscenario,2018-2030SolarPVWindGW800400600300400200200100201820202022STEPSAPSNZE201820202022STEPSAPSNZEWorld20302030RestofworldEuropeUnitedStatesChinaIEA.CCBY4.0.SolarPVandwindcapacityadditionsdoubleby2030intheSTEPSandexpandnearlyfourfoldintheNZEScenarioIEA.CCBY4.0.ChinaisthelargestsolarPVmarket,accountingfor45%ofallcapacityadditionsin2022.Itmaintainsitsleadingroleinallscenarios,accountingforabouthalfofglobalcumulativeadditionsfrom2023to2050intheSTEPSandabout40%intheAPS.ItsrapidgrowthinChapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix147IEA.CCBY4.0.deploymentissupportedbyhugedomesticsolarmanufacturingcapacity(seeChapter1).In2022,thenextlargestmarketsforsolarPVweretheEuropeanUnion(17%ofglobaladditions),UnitedStates(9%)andIndia(8%).Theseremainleadingmarketsinallscenarios,complementedbyincreasingdeploymentinSoutheastAsia,AfricaandtheMiddleEast.Globalwindcapacityadditionsdroppedto75GWin2022.Whilethislevelisnearlyathirdbelowthepeakin2020,itremainsabovedeploymentlevelsbefore2020.Bytheendofthisdecade,globalwindcapacityadditionsriseto175GWperyearintheSTEPSastechnologycontinuestoimproveandcoststofall,thoughadditionalmanufacturingcapacityisrequiredtomeetthislevelofdemand.By2050,annualdeploymentlevelsreach195GW,takingintoaccountreplacementsofageingwindturbines.IntheAPS,240GWofwindcapacityareaddedin2030,increasingto310GWin2050.IntheNZEScenario,thesefiguresriseto320GWin2030and350GWin2050.Offshoreinstallationsaccountforjust15%ofwindcapacityadditionstoday,buttheirshareroughlydoublesby2030acrossallscenarios.Chinaisthelargestmarketforwindpower,asitisforsolarPV.Itaccountedforhalfofglobalcapacityadditionsin2022andisresponsibleforaround40%ofglobalcumulativewindcapacityadditionsfrom2023to2050intheSTEPSandaround28%intheAPS.TheEuropeanUnion(18%ofglobaladditions),UnitedStates(11%)andBrazil(4%)wereotherleadingmarketsin2022andcontinuetobesoacrossallscenarios.ScalingupandmaintainingmuchhigherlevelsofsolarPVandwindpowergenerationrequiresactiontoaddressanumberofbarriers,includingthoserelatedto:Permittingandlicensingofnewprojects.Worktocompletethenecessaryregulatorystepsfornewprojects,includingenvironmentalassessmentswhereapplicable,candelayindividualprojectsbyyearsandslowmarketgrowth.Standardisingandstreamliningtheseprocesses,whileensuringthattheyinvolvelocalcommunities,willbecriticaltocleanenergytransitions(IEA,2023a).Griddevelopmentandconnections.Modernising,digitalisingandreinforcingexistingelectricitynetworkscantakeyears,andthesameistruefortheadditionofnewgridconnections.Streamliningpermittingandlicensingprocesseswouldhelpwiththis,buttimelygriddevelopmentalsocallsforimprovedlong-termplanningandthescalingupofinvestmenttosupporttherapiddeploymentofwindandsolarPV(IEA,2023c).Expandingwindmanufacturingcapacityandimprovingthefinancialhealthofwindsupplychains.Despitelowlevelisedcostsofelectricityandrecentmarketgrowth,themanufactureofturbinesandotherequipmentneededforwindpowerinvolvesthinprofitmarginsasaresultofuncertaintyaboutcommoditypricesandthewaythatauctionschemesareoperated.Measurestomitigatetheserisks,includingthroughcontractterms,areneededtoensurethattheydonotendangerthewindindustryandimpedecleanenergytransitions.EnhancingpowersystemflexibilitytointegraterisingsharesofsolarPVandwind.ActiontoenhancepowersystemflexibilityisessentialtomakethebestuseofsolarPVandwind.Batterystorageanddemandresponsehaveamajorparttoplayinmeetingshort-148InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023termflexibilityneeds,whilehydropowerandthermalsourceswillplayacentralpartintheprovisionofseasonalflexibility(seeChapter4).Reliablesuppliesofcriticalmineralswillalsobeessential.ElectricvehiclesTheshareofEVscarsinglobalcarsalesmorethantripledto14%inthelasttwoyears.Furtherrecordsalelevelsareexpectedin2023,particularlyintheUnitedStates.ChinaisthemostiamrepoinrtCahnitnam,awrkheicthfohraselaelcretraicdycaerxsc:emedoeredtithsa2n0h2a5lftaorfgaeltlftohreneelewcternicercgayrsvoenhicthleesraoleasd.today3IntheSTEPS,nearly40millionelectriccarsarepurchasedin2030,accountingfornearly40%ofallvehiclesales.Thisiswellabovethe25%projectionfor2030intheWEO-2022andnotfarbehindthelevelofpurchasesintheAPS(Figure3.34).ThismoreoptimisticoutlookisduetonewvoluntaryEVtargetsbymajorautomakersaswellasnewvehiclestandards,mandatesandsubsidiesinChina,EuropeanUnionandUnitedStates.IntheNZEScenario,theshareofelectriccarsaccountfortwo-thirdsoftotalsalesby2030.Iftheyallcometofruition,plansthathavebeenannouncedforbatterymanufacturingcapacitywouldbesufficienttomeetdemandforEVbatteriesintheNZEScenarioin2030.Figure3.34⊳Globalshareofelectricvehiclesalesbytypeandscenario,2022and2030Light-dutyvehiclesHeavytrucksTwo/three-wheelers80%60%40%20%2022STEPSAPSNZE2022STEPSAPSNZE2022STEPSAPSNZE203020302030BatteryelectricFuelcellelectricPlug-inhybridelectricIEA.CCBY4.0.ElectriccarsalessharesnearlytripleintheSTEPS,around40%belowNZEScenariolevels,thoughelectrictrucksalesintheSTEPSarenearlyfour-timeslowerthanintheNZEScenarioIEA.CCBY4.0.Two/three-wheelersalreadyhavethehighestelectrificationsharestodayofanyroadtransportmode,inparticularinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,andthatlookssettocontinueasinfrastructurerequirementsandcostpremiumsarelimited.However,lessthan1%ofheavytruckssoldtodayareelectric,andlimitedprogressismadeintheSTEPS,wheresalesin2030arenearlyfour-timeslowerthanintheNZEScenario.MorewidespreadChapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix149deploymentofcharginginfrastructureisneededtoincreasetherateofheavytruckselectrification,especiallyinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Deploymentlevelsarehigherforelectricbuses,whicharealreadycostcompetitiveonalifetimebasisandareoftensubsidisedbylocalmunicipalities.HeatpumpsGlobalsalesofheatpumpsinthebuildingssectorincreasedby11%in2022,markingthesecondyearofdouble-digitgrowthforthiscentraltechnologyintheworld’stransitiontosecureandsustainableheating.Heatpumpsovertooksalesoffossilfuel-basedheatingsystemsinkeymarketssuchasFranceandtheUnitedStates,whilesalesdoubledinvariousEuropeancountrieswherefinancialincentivesandbansonfossilfuelboilershavehelpedtobuildmomentum(section3.3.3).Manufacturingcapacityisexpandingrapidly,andfurtherannouncementsfromkeymanufacturersareexpected,drivenbynewdeploymenttargets,directindustrysupportandincentivesforconsumers.Figure3.35⊳Globalheatpumpsalesandstockbyscenario,2010-2030ShareinheatingequipmentsalesStock60%GWth300040%200020%100020102022STEPSAPSNZE20102022STEPSAPSNZE20302030AdvancedeconomiesEMDEEA.CCBY4.0.Shareofheatpumpsinheatingequipmentsalesdoublesby2030intheSTEPSandincreasesfourfoldintheNZEScenario,triplingglobalheatpumpcapacityNote:EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies;GWth=gigawattsthermal.IEA.CCBY4.0.Today,heatpumpsaccountforaround10%ofsalesofresidentialheatingequipmentworldwide.Salesgrowthisparticularlystrongforair-to-waterheatpumpsinEuropewheretheytypicallyreplacegas-firedboilers.By2030,theshareofheatpumpsinheatingequipmentsalesissettomorethandoubleintheSTEPSandtoreacharoundathirdintheAPS(Figure3.35).Theglobalinstalledcapacityofheatpumpsmorethandoublesby2030intheSTEPSfromaround1000gigawattsthermal(GWth)in2022,whileAPSdeploymentlevelsarecloseto2500GWthby2030.Between2022and2030,globalheatpumpdeploymentsavesmorethan5EJoffossilfuelsintheAPS.However,upfrontcostsoftenremainhigh,150InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023particularlyforlowincomehouseholds,whilethedesignofelectricitytariffsandenergytaxationstillputheatpumpsatadisadvantagerelativetofossilfuelboilersinsomecountries.Meetingexistingtargetsalsorequiresmoreinstallersandfasterprogressincolderclimates,multi-familyapartmentbuildingsandhomeswithretrofitrequirements.EffortsarerampedupfurthertotackletheseobstaclesintheNZEScenario,wheretheglobalheatpumpstockexpandstonearly3000GWthby2030:morethantwo-thirdsofwhichisinstalledinadvancedeconomies.Hydrogen3Progressinscalinguplow-emissionshydrogencontinuesapace,withinvestmentinprojectsreachingUSD1billionin2022andaraftofnewpoliciesaroundtheworldboostingconfidence.8InMay2023,anewrecordwassetfortheworld’slargestoperationalelectrolyserplant–a260megawattfacilityinChinathatwillreplacehydrogenfromnaturalgasinanoilrefinery–anda2GWprojectinSaudiArabiareachedafinalinvestmentdecisionafterthecompany,AirProducts,agreedtoshouldertheoff-takeriskforitsammoniatrade.Increasingly,suchprojectsarelinkedtodedicatedrenewableelectricitysuppliesratherthanrelyingmostlyontheelectricitygrid.Ifallannouncedprojectscometofruition,morethan400GWofelectrolysiscouldbeoperationalby2030.TwoprojectsinCanadaandtheUnitedStateshavestartedconstructiontoproducehydrogenfromnaturalgaswithatargetof95%CO2capture,whichwouldresultinacombinedhydrogencapacityequivalentto1.4GWofelectrolysis(ata90%capacityfactor)(IEA,2023d).Thenear-termoutlookiscloudedbycostinflation,uncertaintyaroundpolicydetailsandsupplychainbottlenecks.IntheSTEPS,7Mtoflow-emissionshydrogenisproducedin2030,mostofwhichreplacesexistingsuppliesofhydrogenforammoniaplantsandrefineries(Figure3.36).IntheAPS,low-emissionshydrogendemandreaches25Mtin2030,andthisrisesintheNZEScenarioto69Mt.ThesetrajectoriesdependonmuchstrongerpoliciesthanthoseintheSTEPStobolsterdemand,financedemonstrationprojectsandsupportinfrastructureexpansion.Dilemmasfacingelectrolysermanufacturersillustratesomeofthevaluechainchallengesforlow-emissionshydrogen.Takentogether,theavailablemanufacturingcapacitiesannouncedbyelectrolysermanufacturerstotal14GW,halfofwhichisinChina,wherethedomesticmarketisincreasingrapidly.However,outputtodatehasbeenmuchlower,estimatedatjustabove1GWin2022,andmanyoftheplantsindevelopmentareprogressingslowlybecausehydrogenproducersarereluctanttocommittoelectrolyserpurchasecontractsatcurrentprices,whichhaverisenduetoinflation.Meanwhile,afallinnaturalgaspricesandacorrespondingincreaseinrelativecostsforelectrolysishydrogenhavespurredcompetitiontomaintainprofitmarginsamongplayersalongthevaluechain.Withouttheopportunitytogetlarge-scalesystemsinstalledquicklyandusedcommercially,manufacturerscannotIEA.CCBY4.0.8Low-emissionshydrogenincludes:thoseproducedfromwaterusingelectricitygeneratedbyrenewablesornuclear,bioenergy,otherfuelsequippedtoavoidgreenhousegasemissions,e.g.viaCCUSwithahighcapturerateandlowupstreammethaneemissions;othersourceswithanequivalentCO2intensity(IEA,2023e).Demandforlow-emissionshydrogenincludesitsusetoproducehydrogen-basedfuels.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix151accumulatesufficientoperatinghourstoprovideindustrystandardperformanceguarantees,exacerbatingrisksandinflatingcostsforthemostefficientdesigns.Thescale-upofproductioninallscenariosispredicatedonabreakinthiscycleandbetterco-ordinationofmanufacturinginvestments,low-emissionshydrogenproductionprojectsanddemandcreation.Figure3.36⊳Globalhydrogendemandbysectorandscenario,2022-2050APSSTEPS2022RefiningIndustry2030Transport2050Transportfuelproduction2030Power2050OtherNZE20302050100200300400MilliontonnesofhydrogenIEA.CCBY4.0.Demandforlow-emissionshydrogenincreases60%peryearto2030intheAPS,butdespitecontinuedstronggrowth,by2050itisatonly60%ofthelevelrequiredintheNZEScenarioNotes:Otherincludesthebuildingsandagriculturesectors.Transportfuelproductionincludesinputstohydrogen-basedfuelsandliquidbiofuelupgrading.Ammoniaforpowergenerationisincludedinpowerinunitsofhydrogeninputtoammoniaplants.IEA.CCBY4.0.Carboncapture,utilisationandstorageForthefirsttimeinadecade,multipleCCUSprojectsareinconstructionaroundtheworld.TotalinvestmentinprojectsreachedarecordUSD3billionin2022.TheoutlookforCCUSisforcontinuedgrowth.MomentumisfuelledbyactivityinNorthAmerica,wheremoregeneroustaxcreditsandnewgrantfundingprogrammesarethedrivingforcesbehindannouncementsofover100projectsacrosstheCCUSvaluechainsinceJanuary2022.Theglobalprojectpipelinenowrepresentsover400MtCO2capturecapacityvyingtobeonlineby2030.IntheUnitedStates,whereafixedamountoffundingisavailablepertonneofCO2safelystored,manyoftheprojectsfocusoncapturingCO2frombioethanolandhydrogenproduction,sincetheseareamongthecheapestoptions.Notableprogressalsoisbeingmadeelsewhere,withinvestmentinlarge-scaleprojectsinCanadaandChina,andkeyregulatoryadvancesinCanada,Denmark,Indonesia,JapanandMalaysia.Currentpolicies,however,arewhollyinsufficienttosupporttheoutcomesthatmatchgovernmentnetzeroemissionspledges.IntheSTEPS,CCUSdeploymentgrowsnearlythreefoldfromthe40MtCO2capturedin2022to115MtCO2in2030(Figure3.37),three-152InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023quartersofwhichisinNorthAmericaandAsiaPacific.ThisincreaseisdwarfedbytheprojectionsintheAPS,whichseesCCUSincreasemorethantenfoldintheperiodto2030.TheAPSalsoprojectsmoreregionaldiversity,withtheshareofcapturedCO2inEuroperisingtoabove15%oftheglobaltotal,overhalfofitintheEuropeanUnion.TherequirementsoftheNZEScenarioareevenmoreambitious,asmorecountriesandsectorsadoptbestavailabletechnologiestomitigateemissionsfromindustrialplantsandtomeetglobaldemandforlow-emissionshydrogen.IntheNZEScenario,around1GtCO2iscapturedin2030,including265MtCO2frombioenergyanddirectaircapture,almost90%ofwhichisgeologicallystored.3Figure3.37⊳GlobalCO2capturedbysourceandscenario,2022-2050NZEAPSSTEPS2022IndustryPower2030Hydrogen2050DirectaircaptureFuelproduction2030205020302050123456GtCO₂IEA.CCBY4.0.MoreCCUSprojectsbecomecompetitiveasclimateambitionsriseandsectorsneedtofullymitigateemissions;NZEScenarioprojects6GtCO2/yearcapturedandstoredby2050IEA.CCBY4.0.ReachingthelevelsofCCUSprojectedintheAPSandNZEScenariorequiresstrongpolicysupport,includingmeasurestofacilitatestrategicinvestmentininfrastructure.Forexample,thetotallengthofexistingCO2pipelinesis9500kilometres(km),whichneedstoincreasetobetween100000and600000kminordertofacilitatethestorageof5.5GtCO2andutilisationofafurther0.6GtCO2intheNZEScenarioby2050(IEA,2023f).Thehighendofthisrangeisasimilarorderofmagnitudetothemorethan1millionkmofnaturalgastransmissionpipelinesthathavecomeonlineoverthepastcentury.Enablingsuchahugescale-up,andaparallelinvestmentinseaborneCO2transport,requiresnewbusinessesthatoffercommercialCO2transportandstorageservices.Therearesignsthattheseareemerginginsomeregions,exemplifiedbythedevelopmentoftheNorthernLightsCO2storageresourceinNorway,wheretherearenowagreementsthatcouldleadtoCO2beingtransportedtothesitefromfacilitiesinDenmark,Netherlands,NorwayandUnitedKingdom.TheEuropeanCommissionhasproposedthatoilandgasproducerstakelegalresponsibilityforensuringthedevelopmentofEuropeanCO2storageresources,initiallytargeting50MtCO2/yearofcapacityby2030.Policydevelopmentsofthistypehavethepotentialtoaccelerateprogress.Chapter3Pathwaysfortheenergymix153IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitionsCriticalingredientsforsuccessSUMMARY•Secureenergytransitionsdependonkeepingtheglobalaveragesurfacetemperaturerisebelow1.5°C.Thetemperaturetodayisaround1.2°Cabovepre-industriallevels,andglobalemissionshavenotyetpeaked.IntheStatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS),thetemperaturerisesto1.9°Cin2050and2.4°Cin2100.Thisis0.1°ClowerthanprojectedintheSTEPSfromtheWorldEnergyOutlook-2022,butfarabovethelevelsoftheParisAgreement.IntheAnnouncedPledgesScenario(APS),thetemperaturerisein2100is1.7°C;intheNetZeroEmissionsby2050(NZE)Scenario,thetemperaturepeaksinmid-centuryandfallstoaround1.4°Cin2100.•Energytransitionsdonotbringanendtotraditionalriskstoenergysecurity.GlobaloilandgastradebecomesincreasinglyfocussedonflowsbetweentheMiddleEastandAsia,exposingimporterstoavarietyofrisks.Electricityfacesrisingshort-termflexibilityneedswhichcanbemetthroughdemandresponseandstorage,andrisingseasonalflexibilityneedswhichcanbemetbyhydropowerandthermalsources,allenabledbyexpandingandmodernisinggrids.•Energytransitionsalsobringnewriskstoenergysecurity.Onesetofrisksrelatetosupplychainsforcleanenergytechnologiesandforcriticalminerals.Supplychainsforbotharehighlygeographicallyconcentrated.Diversifiedinvestmenttomeetgrowingdemandcanhelp,butinternationalpartnershipswillalsobenecessary.•Anothersetofrisksrelatetothepeople-centredaspectsofenergytransitions,includingwhattheymeanforaccess,affordabilityandemployment.Thenumberofpeoplewithoutaccesstocleancooking(2.3billion)andelectricity(760million)todayfallbyaround15%to2030intheSTEPS,bytwo-thirdsintheAPS,andtozerointheNZEScenarioinresponsetomeasurestoimproveaccess.Householdenergybillsinadvancedeconomiesfallbynearly20%intheSTEPSto2030,asfossilfuelusedropsandenergyefficiencygainsaccrue.Inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,fossilfuelsubsidiesneedtobephasedoutcarefullytolimitimpactsonhouseholdbudgets.Estimatesofnewjobscreatedrangefrom7millionintheSTEPSto30millionintheNZEScenario:theseincreasesoutweighlossesinfossilfuelandrelatedindustriesbutwilloftenbeinnewlocationsandrequirenewskills.•Prospectsforsecureandpeople-centredenergytransitionsdependonsecuringhighlevelsofinvestment.Energyinvestmentlevelsshowencouragingtrendsforrenewablesandelectricvehicles,buttherearelargeenergyinvestmentgapsinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChina,andinvestmentinmostend-useareasislagginginallregions.Theexpectedlevelofoilandgasinvestmentin2023issimilartotheamountsrequiredintheSTEPSin2030andfarabovethelevelsneededintheAPSandNZEScenario,implyingthattheoilandgasindustrydoesnotexpecttheretobeanysignificantnear-termreductionindemand.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions155COemissionsandCO2emissions(GtCO2)2100temperaturerise33Allfurthertemperaturerisescarryrisks:3537thoseintheSTEPSwouldriskparticularly31extremeconsequencesforglobalSTEPSecosystemsandhumanwell-being.323024HistoricalAPSMediansurfacetemperature19NZE+2.4°C122010+1.7°C62022+1.4°CIndiaNetzero20302100204079China2050SolarPVEuropeanUnionCleantechnologysupplychaingeography158in203064MillionpeopleCleancookingWindwithoutaccessUnitedStates3000Electricity11242000152110006826BatteriesElectrolysersArgentinaChileSTEPS3616APS2854HeatpumpNZEIndonesiaRestofworldSTEPS2010LithiumchemicalDevelopingAsiaAPS202258Sub-SaharanAfrica2030NZECanadaFinlandAccesstomodernenergy8Transitionsdependonplacingpeopleatthecentreof5discussions.Particularhelpisneededforthosethatcurrently72lackaccesstomodernenergyservices.ReinednickelReinedcobalt4.1IntroductionRussia’sinvasionofUkraineturnedstrainsinenergysupplyrelatedtotheCovid-19pandemicintoafull-blownenergycrisis.Consumersaroundtheworldwereexposedtohigherenergybillsandsupplyshortages,providingastarkreminderoftheimportanceofsecure,affordableandpeople-centredenergytransitions,andoftherisksthatcouldunderminesuchtransitions.Traditionalriskstoenergysecuritydonotdisappearinenergytransitions,andtherearepotentialnewvulnerabilitiesinamoreelectrifiedandrenewables-richsystem.Newrisksariseinadditionfromtheimpactthatourchangingclimateisproducingonweatherpatterns.Successfultransitionsalsodependonplacingpeopleatthecentreofdiscussionsaboutthefutureofenergy:theycannotbeachievedwithoutsustainedsupportand4participationfromcitizens,andparticularhelpisneededforthosethatcurrentlylackaccesstomodernenergyservices.Thischapterexaminesseveralkeyaspectsofpeople-centredandsecureenergytransitions.Itisdividedintofoursections:First,ithighlightsthenatureandscaleoftherisksposedinourprojectionsbyarangeofenergy-relatedenvironmentalhazards,includingcarbondioxideandmethaneemissions,andexaminestheirimplicationsfortheglobaltemperatureriseandairpollution.Second,itreviewshowtraditionalandnewenergysecurityhazardsplayoutinthescenarioprojections.Traditionalfuelsecurityriskspersistagainstabackdropofmorefragmentedinternationalenergymarkets,whilenewrisksariseforelectricitysecurityasbothpowersupplyanddemandbecomemorevariable.Inaddition,therearemajoruncertaintiesabouttheresilienceofcleanenergysupplychains,includingforcriticalminerals.Thethirdsectionfurtherdevelopsthepeople-centredaspectsofenergytransitions,startingwiththeprovisionofaccesstoelectricityandtocleancookingfuels.Itexaminestheimplicationsofthescenarioprojectionsfortheaffordabilityofenergysupplyandenergyemployment,aswellasthebehaviouralchangesneededtoachieverapidenergytransitions.Ultimately,theprospectsforaffordable,sustainableandsecureenergysupplyboildowntoquestionsaboutinvestment.Thefourthsectiondiscussescapitalflowstotheenergysectorandlooksatwhatfasterenergytransitionsmeanforinvestmentinfossilfuels.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions1574.2Environmentandclimate4.2.1EmissionstrajectoryandtemperatureoutcomesEmissionsandtemperatureoutcomesbyscenarioTheglobalaveragesurfacetemperaturerisenowstandsataround1.2degreesCelsius(°C)abovepre-industriallevels.Thisyearhasseenanumberofextremeweatherevents,includingheatwavesanddroughtsinmanypartsoftheworld.Thesehavehadmajorimpactsonthoseaffectedbythem.Theyhavealsoputsignificantstrainonpowersystemsbycurtailingsupplyfromsourceslikehydroandthermalpower,anddramaticallyincreasingdemandforspacecooling.Globalenergy-relatedCO2emissionsrosetoanall-timehighof37gigatonnesofcarbondioxide(GtCO2)in2022.IntheStatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS),emissionsremainlargelyflatuntilthelate2020sandthendeclineslowlyto30GtCO2in2050.IntheAnnouncedPledgesScenario(APS),emissionsfallbyjustover2%peryearto31GtCO2in2030andthenfallfurtherto12GtCO2in2050.IntheNetZeroEmissionsby2050(NZE)Scenario,emissionsdropbymorethan5%peryearto24GtCO2in2030andthenfalltonetzeroin2050(Figure4.1).TheNZEScenarioalsoassumesrapidreductionsinCO2emissionsfromlanduse,whichreachnetzerojustafter2030,andinemissionsofallnon-CO2greenhousegases.Figure4.1⊳Globalenergy-relatedandindustrialprocessCO2emissionsbyscenarioandtemperatureriseabovepre-industriallevelsin2100CO2emissionsTemperaturerisein2100404GtCO₂5th-95th°CSTEPSpercentile30333rd-67thpercentileMedian202APS101NZE20102020203020402050NZEAPSSTEPSIEA.CCBY4.0.Temperaturerisein2100is2.4°CintheSTEPSand1.7°CintheAPS:itpeaksatjustunder1.6°Caround2040intheNZEScenarioandthendeclinestoabout1.4°Cby2100IEA.CCBY4.0.Note:GtCO2=gigatonnesofcarbondioxide;STEPS=StatedPoliciesScenario;APS=AnnouncedPledgesScenario;NZE=NetZeroEmissionsby2050Scenario.Source:IEAanalysisbasedonoutputsofMAGICC7.5.3.158InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IntheSTEPS,theglobalaveragesurfacetemperatureincreasesto1.9°Cabovepre-industriallevelsaround2050andisontrackfor2.4°Cin2100andstillhighertemperaturesthereafter.1Inherentuncertaintiesintheearth’sresponsetofutureemissionsmeanthatthereisaone-thirdprobabilityofthetemperatureriseexceeding2.6°CintheSTEPSin2100,andaone-in-twentychanceofitexceeding3.5°C.IntheAPS,thetemperaturerisesmoreslowly,especiallyafter2030,andreachesaround1.7°Cin2100.IntheNZEScenario,thetemperaturerisepeaksjustbelow1.6°Caround2040beforefallingbacktoaround1.4°Cin2100.Allfurthertemperaturerisescarryrisks:thoseintheSTEPSwouldriskparticularlyextremeconsequencesforglobalecosystemsandhumanwell-being.Howbigaretheimplementationandambitiongaps?4TheParisAgreementrequiresallcountriestodevelop,submitandimplementNationallyDeterminedContributions(NDCs)andtosetascheduleforupdatingthemtoincreaseambition.AsofSeptember2023,168NDCshadbeensubmitted,covering195PartiestotheUnitedNationsFrameworkConventiononClimateChange(UNFCCC),andnearly90%hadbeenupdatedsincethefirstNDCround.Figure4.2⊳ProjectedCO2emissionsfromfuelcombustionunderfirstandrevisedNDCsandbyscenarioin2030AdvancedeconomiesEMDEGtCO₂15301020510FirstRevisedSTEPSAPSNZEFirstRevisedSTEPSAPSNZENDCsNDCsAdditionalemissionsreductionsachievedwithsupportIEA.CCBY4.0.AchievingtargetsintherevisedNDCswouldreduceemissionsby5GtCO2fromthelevelinthefirstround,neverthelesssubstantialimplementationandambitiongapsremainNotes:EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.AdditionalemissionsreductionsachievedwithsupportreferstothedifferencebetweenunconditionalandconditionalNDCs.IEA.CCBY4.0.1TemperatureriseestimatesquotedinthissectionrefertothemediantemperaturerisecalculatedusingtheModelfortheAssessmentofGreenhouseGasInducedClimateChange(MAGICC7.5.3).Allchangesintemperaturesarerelativeto1850‐1900andmatchtheIPCC6thAssessmentReportdefinitionofwarmingof0.85°Cbetween1995‐2014(IPCC,2021).Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions159Themostrecentsubmissionshaveloweredprojectedemissionsin2030byaround5GtCO2fromtheNDCsfirstsubmittedin2016,ifalltargetsconditionaloninternationalsupportarereached(Figure4.2).Foradvancedeconomies,achievingtherevisedNDCswouldloweremissionsin2030byaround2.1GtCO2comparedwiththefirstsubmissions.Inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,emissionsin2030undertherevisedNDCswouldbearound2.8GtCO2lowerthaninthefirstroundofsubmissions.Inadvancedeconomies,thereisa0.7GtCO2gapbetweenemissionsprojectedfor2030intherevisedNDCsandtheSTEPS,whichindicatesthatcountrieshavenotyetintroducedallthespecificpoliciesneededtoachievetheirNDCs.Inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,thesituationisreversed,withemissionsintheSTEPSprojections1GtCO2lowerin2030thanundertheirrevisedunconditionalNDCs.ThisindicatesthattheircurrentpoliciesprovidescopefortheirNDCstobemademoreambitious.Inbothadvancedeconomiesandemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,thereisalargeimplementationgapbetweentheSTEPSandtheAPSandalargeambitiongapbetweentheAPSandtheNZEScenario.Inadvancedeconomies,thereisanimplementationgapof1.7GtCO2in2030andanambitiongapof1.8GtCO2.Inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,thereisanimplementationgapof2.5GtCO2in2030andanambitiongapofcloseto5GtCO2.Thissuggeststhatmoreambitiononnetzeroemissionspledgesisrequiredbycountriesaroundtheworld,andthatcountriesneedtodomuchmoretobackuptheirpledgeswithfirmpolicycommitmentsandmeasurestoensuretheirrealisation..Figure4.3⊳Reductionsinenergy-relatedCO2emissionsbyregionandscenario,2022-2030AdvancedEmergingmarketandeconomiesdevelopingeconomies-2Electricity-4Intensiveindustries-6OtherindustriesCarsTrucksAviationandshippingHeatingandcoolingOtherGtCO2-8APSNZEAPSNZEIEA.CCBY4.0.IEA.CCBY4.0.Inbothscenarios,about40%oftotalemissionsreductionsinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiescomefromrenewablesreplacingcoalpower160InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023ThelargestsinglecontributiontoclosingtheambitionandtheimplementationgapsinboththeAPSandtheNZEScenariocomesfromreplacingcoal‐firedpowergenerationwithrenewableenergysources.Inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,theswitchtocleansourcesofelectricitymakesup40%oftotalemissionsreductionsbetweentodayand2030inbothscenarios(Figure4.3).IntheAPS,mostoftheremainingemissionsreductionscomparedwiththeSTEPScomefrommorerapidenergyefficiencyimprovementsandtheelectrificationofend‐uses.Heavyindustrycontributesthelargestshareofreductions,reflectingmorestringentefficiencystandardsthanintheSTEPSandwiderdeploymentoflarge‐scalenearzeroemissionsplantsinenergy‐intensiveindustries.4IntheNZEScenario,therearelargeadditionalemissionsreductionsfromcarsandtrucks,particularlyinadvancedeconomies,reflectingafasterrolloutofelectricvehicles(EVs)andsupportinginfrastructure.Inhard‐to‐abatesectors,suchasaviationandshipping,therisksassociatedwithbeingafirstmoverdetersomefirmsfromadoptinginnovativelow‐emissionstechnologiesduringthisdecadeintheAPS,butmeasurestakenintheNZEScenariocountertheserisksandcontributeemissionsreductionsof0.5GtCO2globally.IEA.CCBY4.0.4.2.2MethaneabatementWhatistheoutlookformethaneemissionsfromfossilfuels?Methaneisresponsibleforaround30%oftheriseinglobaltemperaturessincetheIndustrialRevolution;rapidandsustainedreductionsinmethaneemissionsarekeytolimitingnear-termglobalwarming(IPCC,2021).Theenergysectoraccountsfornearly40%ofmethaneemissionsfromhumanactivity.Methaneemissionsfromfossilfueloperationsaccountforthevastmajorityofenergysectoremissions,andindeedfornearly10%oftotalgreenhousegas(GHG)emissionsfromtheenergysector.Weestimatethatthefossilfuelindustrycouldavoidmorethan70%ofitscurrentmethaneemissionswithexistingtechnology,muchofitatlittleornonetcost.Methaneemissionsfromfossilfueloperationsfallinallscenariosfrom2023to2030:intheSTEPSbyaround20%;intheAPSby40%;andintheNZEScenarioby75%(Figure4.4).Aroundone-thirdofthereductionsintheNZEScenarioareduetoreduceddemandforoil,gasandcoalandtwo-thirdsarefromtherapiddeploymentofemissionsreductionmeasuresandtechnologies.Someofthekeymeasuresincludeastoptoallnon-emergencyflaringandventing,anduniversaladoptionofregularleakdetectionandrepairprogrammes.By2030,allfossilfuelproducersreducetheirmethaneemissionintensitiestolevelssimilartotheworld’sbestoperatorstoday.ChinaandRussiaarethetwolargestemittersofmethanefromfossilfuels.Togethertheyaccountedforaroundone-thirdofmethaneemissionsfromfossilfueloperationsin2022.Neitherhascommittedtoabsolutemethanereductionsbefore2030.However,manycountriesthathavenetzeroemissionsgoalsalsoarenotcurrentlydoingenoughtoaddressmethaneemissions.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions161Figure4.4⊳Methaneemissionsfromfossilfueloperations120ByscenarioBysourceintheNZEScenarioIEA.CCBY4.0.90Mt603020102020203020402050202220302050STEPSAPSCoalNZEOilNaturalgasIEA.CCBY4.0.Ifcountriesmakegoodontheirpledges,methaneemissionswillfallbyaround50Mtto2030;theyfallanadditional45MtintheNZEScenarioNote:Mt=milliontonnes.HowcancuttingmethanefromfossilfuelscontributetotheGlobalMethanePledge?TheGlobalMethanePledgewaslaunchedatCOP26inNovember2021tocatalyseactiontoreducemethaneemissions.LedbytheUnitedStatesandtheEuropeanUnion,150countriesarenowparticipantsandtogetherareresponsibleformorethanhalfofglobalmethaneemissionsfromhumanactivity.ByjoiningthePledge,countriescommittoworktogethertocollectivelyreducemethaneemissionsbyatleast30%below2020levelsby2030.Achievingthe75%cutinmethaneemissionsfromfossilfueloperationsintheNZEScenariowouldlowertotalhuman-causedmethaneemissionsbymorethan25%(Figure4.5).Generally,manyofthesereductionscanbeachievedatverylowcostorwhilegeneratingoverallsavings.Basedonaveragenaturalgaspricesfrom2017to2021,around40%ofemissionsfromoilandgasoperationscouldbeavoidedatnonetcostbecausetheoutlaysfortheabatementmeasuresarelessthanthemarketvalueoftheadditionalgasthatiscaptured.Emissionscouldbereducedveryquicklyifcountriesandcompaniesweretoadoptasetoftriedandtestedmeasuresandpolicytoolsrelatedtoleakdetectionandrepairrequirements,technologystandards,andabanonnon-emergencyflaringandventing.Intheoilandgassector,thesemeasureswouldcutmethaneemissionsfromoperationsbyhalf.Ifadoptedworldwideinthecoalsector,aroundhalfofmethaneemissionscouldbecutbymakingthemostofthepotentialtousecoalminemethaneinminingoperations,orbymakinguseofflaringoroxidationtechnologies.Advancesintechnology,suchasimprovedsatellitecoverageforleakmonitoring,aremakingiteasiertopinpointsourcesofemissionsandtofacilitateabatementinbothsectors,butactionsofarhasbeenslow.162InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Figure4.5⊳MainsourcesofmethaneemissionsfromhumanactivitiesandabatementpotentialbasedonavailabletechnologiesMainsourcesAbatementpotentialAgricultureEnergyWaste45010015050100MtMtTotalOilGasCoalIEA.CCBY4.0.Theenergysectorhasmorenear-termpotentialformethaneabatementthanothersectorsNotes:AbatementpotentialforagricultureandwasteisbasedontheGlobalMethaneAssessment(UNEP,2021).Emissionsfrombiofuelandbiomassburningarenotshown.IEA.CCBY4.0.Whatisneededtoincreaseactiononmethane?MethaneabatementintheenergysectorisoneofthebestoptionsavailabletoreduceGHGemissions(Figure4.6).JustoverUSD75billionincumulativespendingisrequiredto2030tocutmethaneemissionsfromoilandgasoperationsby75%intheNZEScenario,whichislessthan2%ofthenetincomereceivedbythisindustryin2022(IEA,2023a).Thereareavarietyofreasonswhymethaneemissionsfromfossilfueloperationshaveremainedstubbornlyhighinrecentyears,includinginformationgaps,inadequateinfrastructureorunderdevelopedlocalmarketsthatmakeitdifficulttofindaproductiveuseforabatedgas,andmisalignedinvestmentincentivesthat,forexample,ruleoutanyspendingthatdoesnotprovideaquickpayback.Therearevariouswaystospeedupprogress.Thereisaroleforgovernmentsinimplementingandenforcingpoliciesandregulationstoincentiviseorrequireearlycompanyaction,butoil,gasandcoalcompaniescarryprimaryresponsibilityformethaneabatementandshouldmovequicklytowardsazerotoleranceapproachtomethaneemissionswithoutwaitinguntillegislationcompelsthemtodoso.Banks,investorsandinsurershaveanopportunitytoaddtothepressureformorerapidactionbyincorporatingmethaneabatementintotheirengagementwiththehydrocarbonindustrieswiththeaimofpromotingstrictperformancestandards,verifiablemethanereductions,andtransparentandcomparabledisclosuresonmeasuredemissions.Thereisalsoscopeforconsumerstoworkwithsupplierstocreateamarketforcertifiedlow-emissionsfuelsandtoprovideeconomicincentivesformethaneabatement.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions163Figure4.6⊳OilandgasmethaneemissionssavingsandnetcostsbymeasureandindustrysegmentintheNZEScenario,2030ByabatementmeasureByindustrysegment25IEA.CCBY4.0.20Mt15105ReplaceLDARVRUsNewOn-Off-Down-Uncon-leakyprocessesshoreshorestreamventionalequipmentandequipmentCostofmeasures(USD/tCO2-eq)Nonetcost0-10>10IEA.CCBY4.0.Nearly95%ofabatementhasanetcostbelowUSD10pertonneCO2-eqNotes:USD/tCO2-eq=USdollarspertonneofcarbon-dioxideequivalent;LDAR=leakdetectionandrepair;VRUs=vapourrecoveryunits.Onetonneofmethaneisconsideredtobeequivalentto30tonnesofCO2basedonthe100‐yearglobalwarmingpotential(IPCC,2021).OfthetotalUSD75billionrequiredspendingonmethaneabatementto2030intheNZEScenario,weestimatethataboutUSD15-20billionwillbehardtofinancethroughtraditionalchannels(IEA,2023a).Thisincludesspendingrequiredinlowandmiddleincomecountries,atfacilitiesownedandoperatedbynationaloilcompaniesandsmallerindependentcompanies,andformeasuresthatgenerateasmallreturnovertheirlifetime.Anewinternationaleffortisneededfromtheindustry,governmentsandotherstakeholderstofillthisfinancinggap.4.2.3AirqualityOverviewandscenariooutcomesAirpollutionisoneoftheworld’smostsignificantenvironmentalriskstohumanhealth,withone-in-ninedeathslinkedtopoorairquality.Over90%ofpeopleareexposedtopollutedair,2leadingtomorethan6millionprematuredeathsayear–morethantwicethenumberofdeathsduring2020fromCovid-19.Airpollutionalsocompoundsmultiplechronichealthconditions,suchasasthma,andleadstoseriousdiseases,suchaslungcancer.Today,about4.4millionprematuredeathsayeararecausedbybreathingpollutedairfromoutdoorsources(ambientairpollution),andaround3.2millionaretheresultofbreathingpollutedairfromindoorsources(householdairpollution)duemainlytothetraditionaluse2PollutedairisdefinedhereashavingaPM2.5concentrationhigherthan5µg/m3.164InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023ofbiomassforheatingandcooking.Themajorityofprematuredeathsfromambientairpollutionandalmostallofthosefromhouseholdairpollutionareinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,whereairpollutionalsocomeswithasignificanteconomiccost.Itisestimatedtoreduceglobalgrossdomesticproduct(GDP)byaround6%,andtheGDPofsomeemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesbymorethan10%peryear(WorldBank,2022).IntheSTEPS,prematuredeathsattributabletoambientairpollutionincreaseto4.9millionin2030,whileprematuredeathsduetohouseholdairpollutionfalltoaround2.5million(Figure4.7).Theseworldwideresultsmaskstrongregionaldifferences.Around1%ofpeopleinadvancedeconomieshavelong‐termexposuretodaytofineparticulatematter(PM2.5)concentrationsexceeding35microgrammespercubicmetre(µg/m3),theleaststringent4interimtargetoftheWorldHealthOrganization(WHO,2021),whichremainslargelyunchangedto2030intheSTEPS.Incontrast,40%ofpeopleinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesbreatheairwithconcentrationsofPM2.5abovetheleaststringentWHOtargettoday.IntheSTEPSthisreducesonlymarginallyto37%in2030asreductionsinPM2.5emissionsareoffsetbyincreasesintheurbanpopulation.Figure4.7⊳ShareofpeopleexposedtovariousPM2.5concentrationsanddeathsfromhouseholdandambientairpollution,2030StatedPoliciesScenarioMilliondeathsHAPAAPEMDEAdvanced2.54.4economies0.00.5AnnouncedPledgesScenarioEMDE1.34.3Advanced0.00.5economies0.72.4NetZeroEmissionsby2050Scenario0.00.2100%EMDEAdvancedeconomies20%40%60%80%<5µg/m³>35µg/m³5-35µg/m³IEA.CCBY4.0.By2030,thenumberofpeoplebreathingthemostheavilypollutedairis80%lowerintheNZEScenariothanintheSTEPS,resultinginover3millionfewerprematuredeathsNote:µg/m3=microgrammespercubicmetre;HAP=householdairpollution;AAP=ambientairpollution;EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Source:IEAanalysisbasedonIIASAmodelling.IEA.CCBY4.0.IntheAPS,reductionsintheuseoftraditionalbiomasstoheatbuildingsandcutsinpollutantemissionsinindustrybringdownthenumberofpeopleexposedtoconcentrationsofPM2.5Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions165abovetheleaststringentWHOtargetfrom2022levelsby230million(or3%oftheglobalpopulation)in2030.PrematuredeathsfromhouseholdairpollutionintheAPSarearound1.3millionlowerthanintheSTEPSin2030,anddeathsassociatedwithambientairpollutionareabout200000lowerthanintheSTEPS.IntheNZEScenario,thenextdecadebringsdramaticreductionsinprematuredeathsbothfromambientandindoorairpollution.By2030thereare2.5millionfewerprematuredeathsfromhouseholdairpollutionperyearthanin2022,andaround1.7millionfewerprematuredeathsfromambientairpollution.Thebenefitsarelargestinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,wheretheshareofthepopulationexposedtoPM2.5concentrationsabovetheleaststringentWHOtargetfallsbyfour-fifthsto7%in2030.RapidreductionsinairpollutionintheNZEScenarioareachievedwithfeasibleenergyandairqualitypoliciesandproventechnologies.AccesstocleancookingforallisessentialtoreducetheuseofinefficientbiomasscookstovesandassociatedPM2.5emissions,andthereisalotofexperienceindevisingsuccessfulcleancookingprogrammes(section4.4.1).Sincethemajorityoftransportemissionstakeplaceatstreetlevel,andoftenwithindenselypopulatedareas,strictlyenforcedemissionsstandardsinroadtransportarecentraltoreducenitrogenoxides(NOX)emissions,particularlyincities.Achievingreductionsinsulphurdioxide(SO2)emissionsdependstoalargeextentonfuelswitchinginthepowersectorandonincreasingenergyefficiencyinindustry.Thevalueoftheresultantbenefitsistypicallymanytimeshigherthanthecostsofbringingaboutcleanerair.IEA.CCBY4.0.4.3Secureenergytransitions4.3.1FuelsecurityandtradeAttheheightoftheenergycrisisin2022,recordhighnaturalgaspricesweretranslatingintoadailyflowofUSD500millionfromtheEuropeanUniontoRussia.OverayearonfromthestartofRussia’sinvasionofUkraine,energyflowsfromRussiatoEuropehaveslowedtoatrickleandthecontoursofanewglobaloilandgastradebalancearecomingintoview.Russiaisredirectingitsoiland,toalesserextentitsnaturalgas,toAsiaandothernon-Europeanmarkets.However,itsroleinglobaloilandgastradeissettodiminishasaresultofthelong-termeffectsofsanctions,furtherreductionsinexportstoEurope,anddifficultiesinfullyoffsettingthelostvolumebyredirectingexportstoAsia.GlobaloilandgastradeissettobecomeincreasinglyconcentratedonflowsbetweentheMiddleEastandAsia.IntheSTEPS,seabornecrudeoiltradefromtheMiddleEasttoAsiarisesfromaround40%oftotalglobaltradetodaytoaround50%by2050.Asiaisalsothefinaldestinationforthree-quartersofincrementalMiddleEastliquefiednaturalgas(LNG)supplybetween2022and2030(Figure4.8).IntheAPS,developingeconomiesinAsiacontinuetodrawinoilandgasimportsastheybuildtheircleanenergysystems.TheMiddleEast-Asiatraderouteaccountsforsome40%ofallglobaloilandgastradein2030and45%in2050,upfrom35%today.IntheNZEScenario,theshareofthisrouteincreasesfurtherto166InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook202355%by2050evenasthetotalvolumeoftradedeclinesdramatically.ThechangingfueltradepatternsintheAPSandNZEScenariohaveimportantimplicationsforexportersandimportersalikeandraisequestionsabouthowcountriescanworktogethertoavoidsupplydisruptionswhileachievingrapidtransitions.Figure4.8⊳SeabornecrudeoilandLNGtradebyrouteandscenario120STEPSAPSNZE100%OtherroutesIEA.CCBY4.0.AmericastoEuropeEJ75%OtherstoAsia490AmericastoAsia6050%MiddleEasttoAsiaShareofMiddleEasttoAsia(rightaxis)3025%2022203020502030205020302050IEA.CCBY4.0.GlobalcrudeoilandLNGtradeflowsareincreasinglyconcentratedontheroutesbetweentheMiddleEastandAsiainallscenariosNote:EJ=exajoule.HowdoesoilandnaturalgastradechangeintheAPSandNZEScenario?OilandgastradeisrelativelyresilientintheAPSandNZEScenarioto2030:whileoilandnaturalgasdemandfallbyaround6%intheAPSand20%intheNZEScenarioby2030,tradeexpandsby2%intheAPSandfallsbyonly12%intheNZEScenario.Inbothscenarios,sharplydecliningdomesticdemandinNorthAmericaopensalargeproductionsurpluswhichdrivesexportsto2030.DemandinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesinAsiaremainsrelativelyrobustto2030,meaningimportscontinuetorise,withfallingdomesticproductioncontributingtoimportdemandinsomecountries.ThevalueoftradenonethelessdeclinessharplyintheNZEScenarioasoilandnaturalgaspricesdrop(Figure4.9).Therearemanyuncertaintiesabouthowglobaloilandgastrademightevolveunderthepressureofclimatepolicy.IntheAPS,tradeflowsaredeterminedbyexistingcontractualcommitments,thepipelineofprojectsunderdevelopmentinthenearterm,theabilityofmajorproducerstofindexportoutletsinaworldwhereoilandgastradeisshrinking,andthecostofdevelopingnewsuppliesinthelongrun.IntheNZEScenario,tradeflowsaredictatedmorebyshort-runcostsandtheproductionsurplusesthatformasfallingdomesticdemandfreesupadditionalvolumesforexport.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions167Figure4.9⊳AverageannualvalueofoilandnaturalgastradeImportbillExportrevenue2016-20212022STEPS2030APSNZE2000150010005000500100015002000BillionUSD(2022,MER)MiddleEastEurasiaNorthAmericaAfricaC&SAmericaEuropeJapanandKoreaChinaIndiaRestofAsiaPacificIEA.CCBY4.0.ThevalueofglobaloilandgastradeholdssteadyintheSTEPSandtoalesserextentintheAPS;tradevolumesarelowerintheNZEScenario,andlessprofitabletooNote:MER=marketexchangerate;C&SAmerica=CentralandSouthAmerica.Anumberofexportershavesetoutwhytheythinkthattheywillcontinuetothriveevenduringrapidtransitions.Somesaythattheirlowproductioncostswillallowthemtoout-competerivalproducers;otherspointtoloweremissionsintensitiesthanthoseofrivalproducers,orclaimthattheyareabetteroptionintermsofenergysecurity.However,thereisnogettingawayfromthepointthatanynewresourcedevelopmentsintheNZEScenariowouldneedtobematchedbyfasterdeclineselsewheretoavoidoversupplyorfossilfuellock-in,andthatsomeproducerscouldfacelargepotentiallosses.Thesupply-sideassumptionsintheNZEScenariolooktochartamiddlegroundbetweenthevarioustrade-offsthatexist,butothervariantsarepossible.IntheAPSandtheNZEScenario,thereductioninoilandgasproductionresultsinalargedropingovernmentrevenueforproducereconomiesthatinmanycasesrelyonincomefromstate-ownedoilandgascompaniestofundfiscalspending.IntheNZEScenario,governmentsinnetexportingregionscollectaroundUSD375billionfromtheproductionofoilandgasin2030,around50%belowtheaveragetakebetween2017-2021.By2050,thisvaluefallstoaroundUSD90billion(Figure4.10).Thisreductioninstateincomeunderscorestheimportanceofdevelopingeconomicdiversificationstrategies,includingbymakingfulluseofthepotentialforcleanenergy.IEA.CCBY4.0.168InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Figure4.10⊳AverageannualgovernmentrevenuefromoilandnaturalgasproductionandconsumptiontaxesNetexportingregionsNetimportingregionsBillionUSD(2022,MER)2000Production1500Consumption2050100050042017-21STEPSAPSNZE2017-21STEPSAPSNZE20302030IEA.CCBY4.0.ReductionsingovernmentrevenuefromoilandgastaxesaffectexportersandimportersIEA.CCBY4.0.Ontheothersideoftheledger,governmentsalsoearnrevenuefromoilandgasconsumption,forexampleintheformofexcisetaxesongasolineatthepump.Globally,thesetaxesexceedupstreamtaxesandroyaltiesbyafactoroftwo,suggestingthattheshiftawayfromoilandgasmightalsoposemajorfiscalchallengesforsomenetimporters.IntheNZEScenario,consumption-relatedtaxescollectedbynetimportingregionsfallbyUSD750billionbetween2022and2030.Thereducedtaxtakeis,however,smallerasashareofGDPinnetimportingregionsthaninproducereconomiesheavilyreliantonincomefromhydrocarbonproductionandexport.Moreover,thedropinoilandgasimportbillsintheAPSandNZEScenarioimprovestheoveralltradebalanceforimportingcountries.InIndia,forexample,theoilimportbillfallsbyUSD60billion(40%)intheNZEScenarioin2030comparedwith2022.Fiscalbalancescanalsobeshoredupbyincreasingtaxrevenueinotherpartsoftheenergysector,orbyusingleviescollectedfromCO2pricesinplaceoftherevenuesderivedfromthetaxationofoilandgasconsumption.Howcancountriesandcompaniesworktogethertonavigatesecuretransitions?Fragmentedapproachesbyoilandgasproducersandconsumerscouldheightenenergysecurityrisksandgeopoliticaltensionsduringnetzerotransitions.Anymismatchinthepaceofdemandandsupplyreductionscouldcauseveryhighorlowprices,leadingtoturbulentandvolatilemarkets.Uncoordinatedpolicyimplementationcouldleadtooverinvestmentinnewoilandgascapacityortheprematureretirementofexistinginfrastructure,andeitherofthesecouldundermineeffortstobringaboutsecureenergytransitions.Alackofco-operationcouldalsohamperthedevelopmentandsmoothfunctioningofthecomplexvalueschainsthatareneededforlarge-scaletradeinlow-emissionsfuels.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions169Avoidingthesepitfallswillrequirecountriesandcompaniestoworktogether.Thereareseveralwaysforthemtodothis.Clearlong-termplansonthepartofmajorconsumingcountriesandsectorswouldhelpproducerstomakeinformedinfrastructureandcapitalinvestmentdecisions.Iftheseconsumerssignalthattheyintendtoplaceeconomicvalueonproductswithloweremissions,producerswillbeincentivisedtomakecapitalinvestmentstolowertheemissionsintensityoftheirresources.Consumersandproducerscouldinadditionexplorejointinvestmentstolinkcleanenergysupplywithdemand.Manyproducereconomiesholdabundantrenewableresources,aswellassubsurfacedataandexpertiseforpotentialCO2storage:thereisscopeforcountriestoworktogethertoboostinvestmentinrenewablesandtosupporttechnologydemonstrationandjointR&DprojectstounlockCO2storagepotential.Regularbilateralandmultilateraldialoguescouldfurtherimprovemutualunderstandingofpolicygoals,helpavoidpotentialdisruptionsandreducetherisksofstrandedcapital.Thechallengesofscalinguplow-emissionsfuelsofferaclearexampleoftheneedforenhancedco-operationacrossborders.Hydrogentradeisexpectedtoinvolvealmostallregions(Figure4.11).Long-termcontracts,mutuallyagreedstandardsandcertificationschemesarecrucialtounderpinthecapital-intensiveprojectsthatwillbeneeded.Governmentsaroundtheworldhaveanimportantparttoplayinfacilitatingco‐ordinatedandtimelyinvestments,andthismeansinparticularsettingclearpolicyframeworksthatarecompatibleacrossborders.Figure4.11⊳Low-emissionshydrogendemandandproductioninselectedregionsintheAPS,2050UnitedStatesChinaMiddleEastLACEuropeanUnionAustraliaNorthAfricaCanadaKoreaJapan-100-50050100150200bcmeNetimportsDomesticsupplyNetexportsIEA.CCBY4.0.Closeproducer-consumerco-operationiskeytodevelopinganewhydrogenindustryIEA.CCBY4.0.Notes:bcme=billioncubicmetresofnaturalgasequivalent(equivalentto36petajoules).Includestradeofhydrogenandhydrogen-basedfuels.Finalusemaynotbeintheformofgaseoushydrogen.LAC=LatinAmericaandtheCaribbean.170InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20234.3.2ElectricitysecurityElectricityiscentraltomoderneconomies,accountingforaround20%oftotalfinalenergyconsumptiontoday.Thisincreasesinallscenarios,reaching30%intheSTEPSin2050,40%intheAPSandmorethan50%intheNZEScenario.Duetothehigherefficiencyofmanyelectricalprocesses,itsshareofusefulenergyprovidedisevenlarger,risingfrom27%todaytoabout45%intheSTEPSin2050,50%intheAPSand65%intheNZEScenario(Figure4.12).Figure4.12⊳Shareofelectricityinusefulenergydemandbysectorandscenario4STEPS70%APSNZEAgriculture60%TransportServices50%ResidentialIndustry40%30%20%10%2022203020502030205020302050IEA.CCBY4.0.Theshareofelectricityinusefulenergydemandincreasessignificantlyinallscenarios,mostofallintheNZEScenarioIEA.CCBY4.0.Electricitysecuritymeanshavingareliableandstablesupplyofelectricitythatcanmeetdemandatalltimesatanaffordableprice.Electricitysupplyhasalwaysneededtomeetdemandcontinuously,downtothescaleofsecondsorless,tomaintainsystemstability.However,powersystemsarebecomingmorecomplex,andpowersystemflexibilityneedsaresettoincreasesharplyinthefutureasaresultoftherisingshareofvariablewindandsolarphotovoltaics(PV)andrisingelectricitydemand.Inthelightofthesechanges,maintainingelectricitysecurityinfuturepowersystemscallsfornewtoolsandapproaches.Powergeneratorswillneedtobemoreagile,consumerswillneedtobemoreconnectedandresponsive,andgridinfrastructurewillneedtobestrengthenedanddigitalisedtosupportmoredynamicflowsofelectricityandinformation.Sufficientflexiblecapacitywillhavetobeavailabletodealwithvariabilityacrossalltimescales,fromtheveryshorttermtotheverylongterm,acrossseasonsandyears.Powersystemswillalsoneedtoadapttobothchangingclimateandweatherpatternsaswellaschangingconsumerbehaviour(Box4.1).Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions171Howareincreasingpowersystemflexibilityneedsmetinthefuture?Mostoftheflexibilityrequiredacrossalltimescalestodayisprovidedbydispatchablethermalpowerplantsandhydropower(includingpumpedstorage).3Inourthreescenarios,muchoftheadditionalshort-termflexibilitythatisneededisprovidedbybatteriesanddemandresponse,especiallyafter2030.Thermalpowerplantsandhydropowercontinuetoprovidemostseasonalflexibility,withdemandresponseandcurtailmentofsurplusgenerationplayinganincreasinglyimportantroletowardstheendoftheoutlookperiod.Figure4.13⊳GlobalpowersystemflexibilityneedsandsupplyintheAPSShorttermSeasonal5Flexibilityneeds(2022=1)4FlexibilityneedsdriverDemandWindSolarPV3FlexibilitysupplyCurtailment2ThermalHydro1BatteriesDemandresponse202220302050202220302050IEA.CCBY4.0.Short-termneedsincreasesignificantly,mainlyduetosolarPV,withbatteriesanddemandresponseemergingascrucialsuppliersofflexibility;seasonalneedsriselesssharplyNotes:Flexibilityneedsarecomputedfor2030and2050takingintoaccountchangesinelectricitysupplyanddemandandweathervariabilityover30historicalyears.Demandresponseincludestheflexibleoperationofelectrolysers.IntheSTEPS,short-termpowersystemflexibilityneedsmorethantriplegloballyby2050relativetotoday.IntheAPS,theydoubleby2030andrise4.5-foldby2050(Figure4.13).Globalneedsforseasonalflexibilityincreaselesssharply:theyrisebynearly20%to2030and45%to2050intheAPS.Thefast-risingshareofsolarPVemergesasthekeyfactorincreasingshort-termflexibilityneeds:windislessvariableintheshorttermbutcanvarysignificantlyacrossweeksorseasons,anditbecomesanimportantdriverofseasonalflexibilityneedsasitsshareincreasesinpowersystemsacrosstheworld.Patternsofwindandsolaroutputcanbecomplementarytovariationsinelectricitydemand,buttheirrisingsharetendstoincreaseoverallsystemflexibilityneeds.IEA.CCBY4.0.3Flexibilityisdefinedastheabilityofapowersystemtoreliablyandcosteffectivelymanagethevariabilityofdemandandsupply.Itrangesfromensuringtheinstantaneousstabilityofthepowersystemtosupportinglong-termsecurityofsupply.172InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Risingflexibilityneedsandchangesintheglobalpowerplantfleet–withthephase-outofunabatedcoalinmanyregions–seetheshareofshort-termflexibilityprovidedbythermalpowerplantsdropfromaround60%todaytoone-thirdby2030intheAPS.Thermalpowerplants,includingunabatedfossilfuelplantsandlow-emissionstechnologies(suchasnuclear,fossilfuelswithcarboncapture,utilisationandstorage,bioenergy,hydrogenandammonia),remainimportantprovidersofseasonalflexibilitythroughto2040.Itisonlyby2050thattheirshareintheflexibilitymixdropstoabout10%.Theshareofhydropowerinthesupplyofshort-termflexibilityfallsasneedsincreaserapidly,butitremainsanimportantsourceofseasonalflexibilityandisthemainsourceoftheseasonalbalancingrequiredafter2040.Marketdesignsandregulationsneedtoensurethatthedispatchofpumpedstorage,reservoirhydropowerandotherformsoflong-termenergystorageisalignedwiththe4long-termflexibilityneedsofthesystem.Demandresponseissettoplayanincreasinglyimportantpartintheprovisionofshort-termflexibilityasthecontributionmadebythermalpowerplantswanes.Expandinguseofelectricheatpumps,airconditionersandEVsmakesdemandmorevariable,butitalsocreatesadditionalopportunitiesfordemand-sideresponse.Makingthemostoftheseopportunitiesdependsonthecreationofasupportiveregulatoryenvironmentwhichisunderpinnedbyadequatepricesignals,digitaltoolsandsmartcontrols.Effectivedemand-responsepoliciesandinstrumentscanalsohelpconsumersreducetheirelectricitybills(Box4.3).IntheAPS,demandresponsemeetsaroundone-thirdofshort-termflexibilityneedsby2030.Figure4.14⊳HourlyelectricitygenerationbysourceforasampledayinIndiainAugustintheAPS,2022and205020222050GW2501500SolarPVWind2001200BatterystorageHydro150900OilNaturalgas100600CoalNuclear50300OtherDemandDemandwithDRDemandwithDR,BC0h24h0h24hIEA.CCBY4.0.ElectricitysystemsneedtobecomemoreflexibletocopewithlargeincreasesinelectricityconsumptionandarisingshareofelectricityfromvariablerenewablesIEA.CCBY4.0.Notes:GW=gigawatt;DR=demandresponse;BC=batterycharging.Demandresponseincludestheflexibleoperationofelectrolysers.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions173Batteriesareemergingasacrucialmeansofprovidingshort-termflexibilityalongsidedemand-responsemeasures.Utility-scalebatterystoragecapacityincreasesnearly85-foldintheSTEPS,risingtomorethan2terawatts(TW)by2050.IntheAPSitincreasestojustover3TWby2050andprovidesroughlyone-thirdoftheshort-termflexibilityneededin2050.BatteriesareagoodmatchforthedailycycleofsolarPV-basedelectricitygenerationinparticular.OnatypicaldayinIndiain2050,forexample,batteriescouldchargeusingexcesssolargenerationduringthedaytimeanddischargeatnight,reducingcurtailmentandtheneedtocyclethermalpowerplantsoverthecourseofaday(Figure4.14).Therearealsootheroptionsfortheprovisionofbothshort-termandseasonalflexibility.Low-emissionshydrogenandammoniacanbeusedinthermalpowerplantstoprovidebackupcapacity,actingineffectasseasonalstorageofrenewableelectricity.Grid-connectedelectrolyserscanoffersignificantamountsofbothshort-termandseasonalflexiblecapacity:electrolysersprovideroughlyaquarteroftheseasonalflexibilityneededin2050intheAPS.Insystemswithhighsharesofvariablerenewables,itmayalsobeeconomicaltocurtailsomeofthesurpluswindorsolarPVgenerationtoprovideadditionalflexibilityifothersourcesofflexibilityareunavailableormorecostlytodispatch.Figure4.15⊳Electricitypeakdemandinselectedregionsandcountriesandcontributionsbysector,2022-2050EuropeanJapanUnitedChinaIndiaSoutheastUnionStatesAsiaIndex(2022=1)5Transport43Buildings2Cooling1HeatingOtherIndustryAveragedemand2022STEPSAPS2022STEPSAPS2022STEPSAPS2022STEPSAPS2022STEPSAPS2022STEPSAPS205020502050205020502050IEA.CCBY4.0.Peakelectricitydemandincreasesinallregions;itrisesfasterthanaveragedemandinmostregionsNotes:Peakdemandhereistheaverageofdemandforthe500highestloadhoursoftheyear,beforeactivationofdemandresponse.Heatingincludeswaterheating.IEA.CCBY4.0.Changingpatternsofconsumptionaselectricityuseincreaseshaveasignificantimpactonpeakelectricitydemandovertheyear(Figure4.15).IntheSTEPS,peakdemandincreasesby174InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook202337%intheUnitedStatesand65%intheEuropeanUnionto2050.Theincreaseismorepronouncedincountrieswithsignificantspacecoolingneedsasmorepeoplestarttouseairconditioners.InIndia,forexample,thereisafourfoldincreaseinpeakelectricitydemandby2050asaresultofexpandingelectrification,increaseduseofairconditionersandEVcharging.Energyefficiencyhasavitalparttoplayinmitigatingtheincreaseinpeakdemandandreducingstressonelectricitynetworks.Thecontributionofairconditioningtopeakdemand,forexample,iscutbyhalfinIndiaandbytwo-thirdsintheUnitedStatesintheAPScomparedwiththeSTEPSin2050bymorestringentminimumenergyperformancestandardsandmoreeenffdic-iuesnetsbwuiitldhinsiggndiefisciagnnts.flSeixnicbeiliatylaprogteensthiaarl,esuocfhthaesiEnVcsr,eaaisrecoinndpietaiokndeersmaannddhiseadtrpivuemnpbsy,4increasesinuncontrolledpeakdemandcanbealsomitigatedbydemand-sideresponsemeasures.Box4.1⊳Impactsofweatheronpowersystems:CasestudyofEuropeFigure4.16⊳VariabilityofflexibilityneedsandgenerationfordifferentweatheryearsinEuropeintheAPS,2030DifferencetoaverageweatheryearFexibilityneedsFlexibilityneedsdriversElectricitygeneration30%10%40%15%SolarPV20%generation5%0%0%0%Short-termDemand-20%Hydro-15%-5%-30%Seasonal-10%Wind-40%NaturalgasgenerationIEA.CCBY4.0.Seasonalflexibilityneedscanvarysignificantly,leadingtolargedifferencesintheloadfactorofthedispatchablepowerplantfleetfromoneyeartothenextNote:Aweatheryearisasetofweatherparameterssuchastemperature,solarradiation,windspeedandprecipitationcompiledfromhistoricalrecordstocreatecurvesofhourlyloadsandrenewablesoutput.IEA.CCBY4.0.Toexaminehowseasonalflexibilityneedscouldvaryacrossyears,weanalysedhowthepowersysteminEuropewouldneedtoevolveintheAPSto2030and2050tobeabletohandle30differentpossibleweatheryears(Figure4.16).AstheshareofwindandsolarPVinpowergenerationincreasesattheexpenseoffossilfuelsthefrequencyandChapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions175durationoflowwindperiodscoincidingwithcloudyskiesandlowtemperaturesisasignificantcontributortoseasonalflexibilityneeds.Thishasasubstantialimpactontheoperationofthedispatchablepowerfleet,notablynaturalgas-firedplantsandhydropower,whichmustabsorbmostofthevariationbetweenseasonsandyears.In2030,themostextremeconditionsinaweatheryearcouldinducea40%upwardordownwardvariationintheannualuseofgas-firedpowerplantsinEuropecomparedwithanaverageweatheryear.Theresultantuncertaintyaboutrevenuesfortheseplantsandabouttheirprofitabilitycouldactasadragoninvestmentinthem,despitetheiressentialroleasprovidersofsystemadequacyandflexibility.Adaptingmarketdesignsandestablishinginstrumentstoensuresufficientinvestmentisessentialforsecurityofsupply.Short-termflexibilityneedsmorethanquadrupleby2050intheAPScomparedwiththecurrentlevel,mainlybecauseoftheintegrationofvariablerenewables.For2030,differencesbetweenweatheryearshavelessimpactonthemagnitudeoftheserequirements:theyvarybyaround5%upwardsordownwardscomparedwithanaverageweatheryear.Willgridsbereadyintimetoenablepowersectortransitions?Thereareapproximately80millionkilometres(km)ofelectricitynetworksworldwidetoday.Significantgridenhancementsareneededinallscenariostomeettheincreasingpaceofelectrificationandaccelerateddeploymentofrenewableenergysources.4Newtransmissionlinesarenecessarytoconnectlarge-scalewindandsolarPVprojectstodemandcentres,sometimesoverlongdistances,andoffshoresubstationsandcablingareneededtoconnectthenewandplannedoffshorewindfarmstothemainland.DistributionlinesalsoneedtobeexpandedtoaccommodateincreasingelectricitydemandandtherapidgrowthofdistributedsolarPVcapacity.Furtherlinkswithinandbetweencountriesandregionsareneededtoreducetherequirementforflexibilityfromalternativesourcesandtofacilitatetheintegrationoffurtherpotentialflexibilityproviders.Totalgridlinelengthsincreasebyabout18%from2022to2030intheSTEPSandAPS,andby20%intheNZEScenario.Inadditiontotheextensionofpowerlines,investmentindigitalisation,smartsystemsandadvancedhighpowersemiconductortechnologiesisneededtoimprovethecontrolandstabilityofelectricityflows.Smartgridsandgridcomponentssuchasflexiblealternatingcurrent(AC)transmissionsystemsmakeiteasiertoaccommodatetheincreasingshareofvariablegenerationfromsolarPVandwind.Theyalsopresentanopportunitytoimprovegridmanagementandtomakenewinvestmentingridsmoretargetedandefficient.Thismeansthatamajorincreaseininvestmentisrequiredtoensuregridreliability,supportcleanenergytransitionsandachieveuniversalelectricityaccess(Box4.2).SomenewIEA.CCBY4.0.4SeeElectricityGridsandSecureEnergyTransitions(IEA,2023b)foracomprehensiveanalysisontheroleofgrids.176InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023investmentisalreadyplanned:thepipelineofannouncedhighvoltagedirectcurrent(HVDC)projectsissettoleadtoanincreaseinthelengthofHVDClinesbyaround45%to2030.ObtainingthenecessarynewinvestmentandbuildingthenewgridinfrastructurerequiredintheAPSandtheNZEScenarioischallengingbutfeasible.However,earlyactionandholisticplanningareneededtoavoiddelaysinconnectingsourcesofrenewableenergy,giventhatgridprojectscantakemorethanadecadeandtypicallyhavemuchlongertimelinesthanrenewableenergyprojects,andmeasurestoexpeditepermittingprocessesfornewgridinfrastructurewouldhelpagreatdeal.Box4.2⊳ScalingupinvestmentinelectricitynetworksThereisagapbetweencurrentgridspendingtrendsandtheinvestmentrequiredto4reachclimategoals,especiallyinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.AnnualinvestmentingridsworldwideissettoreachUSD330billionin2023.ThisclimbstoUSD565billionby2030intheSTEPS,butitneedstorisefurthertoaroundUSD620billionintheAPSandUSD680billionintheNZEScenario.Basedonrecenttrends,spendingin2030inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomieswouldbelessthanhalftheinvestmentneedsoftheAPS(USD335billion),whilethegapinadvancedeconomiesisfarsmaller(Figure4.17).Figure4.17⊳InvestmenttrendsingridsversusneedsintheAPSAdvancedeconomiesEmergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesBillionUSD(2022,MER)40030020010020192023e203020192023e2030APSAPS2019-23eCAAGRIEA.CCBY4.0.Recenttrendsingridinvestmentleavealargegapwiththerequiredlevelsby2030,especiallyinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesNote:MER=marketexchangerate;CAAGR=compoundaverageannualgrowthrate;2023e=estimatedvaluesfor2023.IEA.CCBY4.0.Manyadvancedeconomies,includingItaly,Spain,UnitedKingdomandUnitedStates,aresufferingfromgridconnectionqueuesforwindandsolarprojects.Permittingrules,planningandremunerationforinvestmentsarethekeyissuesrequiringpolicyattention.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions177However,thebiggestchallengesareinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,whereresponsibilityforinvestmentoftenlieswithcash-constrainedandheavilyindebtedpublicutilities.Forexample,theSouthAfricautility,Eskom,hasaroundUSD20billionofguaranteeddebtatriskofdefault,raisingSouthAfrica’sriskpremiumandborrowingcosts.Concessionalfundingfrominternationaldevelopmentfinanceinstitutions(DFIs)offersonewayoutofthisimpasse.Thisneedstobeaccompaniedbyreformsthataimtocreatehealthierutilitiesandbusinessmodels.Itisnoteasytobringaboutsuchreforms:manydevelopingcountryutilitieshaveamajorityoflowincomecustomerswhichcannotaffordhigherelectricityprices,andinnovativeapproacheswillbeneeded.InthecaseofEskom,theNationalTreasuryinSouthAfricahasdevelopedadebt-reliefarrangementofaroundUSD15billionasaninterest-freesub-ordinatedloan,whichwillimprovethedebt-equityratioandbalancesheet.Despiteaheavyrelianceonpublicfundingwhendevelopingconcessionalfinanceandreformpackages,thereisscopeforDFIsandgovernmentstodevelopbusinessmodelsthatallowtheprivatesectortoparticipateingriddevelopmentandstrengthening.Forexample,independentpowertransmission(IPT)projectsaredesignedtoofferrightsoveraspecifictransmissionlinethroughatenderingprocess.Governmentsandstate-ownedenterprisescanbeinvolvedintheownershipandoperationalriskoftheproject,dependingonthetypeofIPTcontract.ThismodelhasrecentlybeenintroducedinAfrica,andsimilararrangementshavepreviouslybeenimplementedsuccessfullyinBrazilandColombia.IEA.CCBY4.0.4.3.3CleanenergysupplychainsandcriticalmineralsThedevelopmentofcleanenergytechnologysupplychainshasmadeimpressiveprogresssince2015,boostedrecentlybystimulusspendingrelatedtotheCovid-19pandemic,theresponsefromgovernmentstotheglobalenergycrisis,andgrowingcommercialandgeopoliticalcompetition.Progresshasbeenparticularlyfastinthemanufacturingsegment,notablyforsolarpanelsandbatteries,wherenewfacilitiesarebenefitingfromstandardisationandshortleadtimes.Thepipelineofannouncedmanufacturingprojectsisexpandingrapidly.IfallannouncedsolarPVmodulemanufacturingprojectscometofruition,theircombinedoutputglobally,togetherwiththatfromtheincreasedutilisationofexistingcapacity,wouldexceedthedeploymentneedsoftheNZEScenarioin2030;EVandgridstoragebatteryneedsfor2030wouldalmostbemetonthesamebasis(Figure4.18).Theexpectedpaceofgrowthincriticalmineralsuppliesdoesnotmatchthatofcleanenergytechnologymanufacturingcapacityadditions,althoughanincreasingnumberofnewprojectshaverecentlybeenannounced.Theoverallpaceoftransitionisusuallydeterminedbytheslowest-movingcomponent,andthatmakesitimportanttostrengtheneffortstoscaleupinvestmentincriticalmineralsupplies.178InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Figure4.18⊳Announcedprojectthroughput,anddeploymentandsupplyneedsforkeycleanenergytechnologiesandmineralsin2030150%Production100%2022NZE2030deploymentWithincreasedutilisationAnnouncedprojects450%APS2030deploymentSolarPVBatteriesCopperLithiumNickelIEA.CCBY4.0.ProgressonthedevelopmentofcleanenergysupplychainshasbeenunevenNotes:Announcedpipelineincludesbothcommittedandpreliminaryprojects.Forcriticalminerals,theNZEScenariodeploymentneedsrefertotheprimarysupplyrequirements(totaldemandlesssecondarysupply).Ahighdegreeofsupplychainconcentrationremainsamajorconcernforbothcleanenergytechnologymanufacturingandcriticalmineralsasitcanmaketheentiresupplychainvulnerabletoindividualcountrypolicychoices,companydecisions,naturaldisastersortechnicalfailures.IEA.CCBY4.0.Howcanweacceleratethediversificationofcleanenergymanufacturing?Cleanenergytechnologysupplychainstodayaremoregeographicallyconcentratedthanfossilfuelsupplychains.Chinahasanoutsizedpresenceinmostofthem,andtheyaregenerallydominatedbyasmallnumberofcountries.ForkeycleanenergytechnologiessuchassolarPV,batteriesandelectrolysers,forexample,thelargestthreeregionsaccountfor80-90%ofglobalcapacity,withthelargestsingleproduceraccountingforupto80%(IEA,2023c).Manycountriesarecompetingtosecuretheirplaceinthenewglobalenergyeconomy.Thepipelineofannouncedprojectsforcleanenergytechnologymanufacturingshowssomepositivesignsintermsofdiversification,butthesituationvariesbytechnology(Figure4.19).Inthecaseofbatteries,electrolysersandheatpumps,manyprojectsarenowbeingdeveloped,notablyintheUnitedStatesandEurope,which–iftheyallcometofruition–wouldleadtoamoderatedecreaseinChina’sshareofthemarket.However,ChinaissettomaintainadominantpositionforsolarPVandwindthisdecade.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions179Figure4.19⊳Shareoftopthreemanufacturingregionsforkeycleanenergytechnologiesin2023and2030basedonannouncedprojects100%SolarPVWindBatteriesElectrolysersHeatpumps75%50%RestofworldUnitedStatesEuropeanUnionIndiaVietNamChina25%Current2030Current2030Current2030Current2030Current2030IEA.CCBY4.0.Announcedprojects–ifallrealised–willaltertheglobaldistributionofmanufacturingcapacityforbatteries,electrolysersandheatpumpsNotes:Wind=onshorenacelles.Electrolysersonlyincludesprojectswithavailablelocationdata.Figurefor2023referstoinstalledcapacityasofQ12023;figurefor2030referstoproductionin2030fromallexistingandprojectsannouncedtodate.Toaccelerateprogressondiversifyingsupplychains,countriesneedbothtodevelopdedicatedindustrialstrategiesandtostrengtheninternationalco-operation.Itisclearlycrucialinthiscontexttoidentifyandmonitorthemajorcleanenergytechnologysupplychainrisksthatcoulddelayordisruptdeployment,giventhatsupplychainsareonlyasstrongastheirweakestlink.Buildingstrategicpartnershipsisalsocrucial.Itisnotrealisticorefficientformostcountriestoseektocompeteinallpartsofallsupplychains.Identifyingrelativestrengthsandseekingcomplementarypartnershipsshouldbeattheheartofthedevelopmentofindustrialstrategiesforcleantechnologymanufacturing.Moreattentionalsoneedstobepaidtoopportunitiestosupportin-countryenergytransitionsandsocioeconomicdevelopmentinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.IEA.CCBY4.0.Areweontracktoensurediversifiedandresilientcriticalmineralsupplies?Criticalminerals,whichareessentialforarangeofcleanenergytechnologies,haverisenupthepolicyagendainrecentyearsinthewakeofincreasingdemand,volatilepricemovements,supplychainbottlenecksandgeopoliticalconcerns.Demandforcriticalmineralsforcleanenergytechnologiesissettoincreaserapidlyinallofthescenarios.IntheAPS,demandalmosttriplesby2030.IntheNZEScenario,afasterdeploymentofcleanenergytechnologiesimpliesanalmostfourfoldincreaseindemandforcriticalmineralsin2030,comparedwithtoday.EVsandbatterystoragearethemaindriversofdemandgrowth,buttherearealsomajorcontributionsfromlow-emissionspowergenerationandelectricity180InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023networks.Asdemandforcleanenergyapplicationsexpandsfasterthanotheruses,theshareofcleanenergyintotaldemandforkeymineralsrisesconsiderably:intheAPS,itreachesover80%forlithium,nearly60%forcobaltandaround40%fornickelandcopperin2030.Meetingthesedemandsrequiresasignificantramp-upinminingandrefiningactivities,especiallyingeographicallydiversifiedregions.Inadequatemineralsuppliescouldmakeenergytransitionsslowerormoreexpensive,andthereversalin2021and2022ofadecade-longreductionincleanenergytechnologycostsservedasareminderthatsteadyincreasesinsupplyanddecreasesinpricecannotbetakenforgranted.Concernsaboutsecurityofsupplyhavealreadypromptedmanycountriestointroducearangeofpoliciesdmeasnigunfeacdtutoresrescaunredobrapttreormyocteellmminakeerarslsaurpepalilesso.bMeacnoymdinogwinnsvtorelvaemdcinomthpeancireitsicsaulcmhianseEraVl4valuechainthroughstrategicinvestmentsinminingandrefiningoperations.Long-termoff-takeagreementshavebecomethenorm,andtherehasbeenanotableincreaseindirectinvestmentactivitiessince2021(Table4.1).Table4.1⊳Involvementoftop-sevenEVandbatterymakersinthecriticalmineralssupplychainEVmakersLong-termMiningRefiningBatteryLong-termMiningRefiningoff-takemakersoff-take●●●●BYD●●●●●CATL●●●●●●●●Tesla●●●●●●LGEnergy●●Solution●●●●Volkswagen●●●●●●BYDGeneral●●●●●●Panasonic●●MotorsStellantis●●●●SKOn●●Hyundai●●SamsungSDI●●BMW●●●●CALB●Before2021●Since2021Note:CATL=ContemporaryAmperexTechnologyCompanyLimited.Source:IEAanalysisbasedoncompanyannouncementsandnewsarticles.IEA.CCBY4.0.Therearesomepositivesignsintermsofnewsupply.Investmentincriticalmineralsdevelopmentroseby30%in2022,andthisfolloweda20%increasein2021.Explorationspendingalsoroseby20%in2022,drivenbyrecordgrowthinlithiumexploration,especiallyinCanadaandAustralia.Criticalmineralsstart-upsraisedarecordUSD1.6billionin2022,a160%increasefrom2021,despiteheadwindsinthewiderventurecapitalsector(IEA,2023c).Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions181TheseincreasesincapitalspendingindicatethatsupplyiscatchingupwithnationalcleanenergyambitionsasreflectedintheAPS.MeetingtherequirementsintheNZEScenariodependshoweveronfurtherprojectscomingthrough.Moreover,theadequacyofplannedfuturesupplyisfarfromassured.Delaysandcostoverrunshaveoccurredregularlyinthepast.Thesupplyofbattery-gradeandhigh-qualityproductsmaystillbeconstrainedevenwhenanoverallbalanceofsupplyanddemandisachieved.Andnewminingplaysoftencomewithhigherproductioncosts,whichcouldpushupmarginalcostsandprices.Whilesomeprogresshasbeenmadeinincreasingsupplies,limitedprogresshasbeenmadeindiversifyingsupplysources;thesituationhasevenworsenedinsomecases.Theshareofthetop-threeproducersin2022iseitherunchangedorhasincreasedfrom2019levels,especiallyfornickelandcobalt.Ouranalysisofprojectpipelinesindicatesthatconcentrationlevelsin2030aresettoremainhigh,especiallyforrefiningoperations,whichiswherethecurrentgeographicalconcentrationisstrongest.Manyplannedprojectsarebeingdevelopedinthecurrentdominantregions,withChinaholdinghalfofplannedlithiumchemicalplantsandIndonesiarepresentingnearly90%ofplannednickelrefiningfacilities(Figure4.20).ThisheightensconsumerexposuretovariousgeopoliticaleventsashighlightedbytheexportcurbsongalliumandgermaniumfromChinainAugust2023.FromAfricatoLatinAmericaandtheCaribbean,manyresource-holdingnationsareseekingpositionsfurtherupthevaluechainwhilemanyconsumingcountrieswanttodiversifytheirsourceofrefinedmetalsupplies.However,theworldhasnotyetsuccessfullyconnectedthedotstobuilddiversifiedmidstreamsupplychains.Figure4.20⊳Geographicconcentrationofrefinedkeymineralsupplyin2022andin2030basedonannouncedprojectsLithiumchemicalRefinednickelRefinedcobalt100%Restofworld80%Canada60%Finland40%RussiaArgentinaChileChinaIndonesia20%202220302022203020222030IEA.CCBY4.0.Projectpipelinesindicatethat,inmostcases,thegeographicalconcentrationofmineralrefiningoperationsislikelytoremainhighto2030IEA.CCBY4.0.Note:Figurefor2030referstoproductionin2030fromallexistingandprojectsannouncedtodate.Sources:IEAanalysisbasedonS&PGlobal(2023);WoodMackenzie(2023);BenchmarkMineralIntelligence(2023).182InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Marketbalancesdonotjustdependonsupply.Thereissignificantscopeforactionsonthedemandsidetoeasepotentialstrains,viarecycling,technologydevelopment,smallerEVsandsoon.Forexample,theaveragebatterysizeforpassengerelectriccarshasbeenonarisingtrendinnearlyeverymajormarketasthedesireforlargervehiclesasinconventionalcarmarketsisreplicatedintheEVmarket.Ifthistrendpersists,itwouldpushupmaterialdemandforbatteriesby15%in2030intheNZEScenario.Ontheotherhand,thefasteradoptionoftechnologiessuchassodium-ionbatteriesorlithium-ionphosphatechemistriescouldreducematerialdemandby7%in2030.Progresstowardsimprovingsustainableandresponsiblepracticeshasbeenmixed.Ourcaossmepssamnieenstaoreftmhaekeinngvihreoandmweanytaolnasnodcisaolciniadlipcaetroforsrmsuacnhceasocfommamjourncitoyminpvaensitemsesnhto,wwsotrhkeart4safetyandgenderbalance.However,environmentalindicatorssuchasGHGemissions,wasteandwaterusearenotimprovingatthesamerate,andtherearefewsignsthatend-usersareprioritisingcleanerproductionpathwaysintheirsourcingandinvestmentdecisions,althoughsomedownstreamcompanieshavestartedtogivepreferencetomineralswithlowerclimateimpact.Everycountry’sstrategyoncriticalmineralswillinevitablyreflectitsspecificcircumstances,butkeycomponentsarelikelytoincludeinvestment,innovation,recyclingandrigoroussustainabilitystandards.Moreco-operativeapproachesbetweenproducersandconsumerscouldhelptobuildmorediversesupplychainsandensurefairaccesstorawmaterials.Moresupportforfurthertechnologicalinnovationandrecycling,whichhasalreadyshownitsabilitytorelievesomeofthepressureonprimarysupplies,couldbringfurtherimprovements.4.4People-centredtransitions4.4.1EnergyaccessThenumberofpeoplewithoutaccesstoelectricityworldwidehasdecreasedbymorethan45%since2010,primarilydrivenbyprogressindevelopingAsia,but760millionpeoplestilllackaccesstoday(Figure4.21).Thesituationismostpressingincountriesinsub-SaharanAfrica,wherearound80%ofpeoplewithoutaccesstoelectricitylive.Whiletherehavebeensomerecentimprovementsinaccessinsub-SaharanAfrica,thesehavenotkeptpacewithpopulationgrowth,withtheresultthattherehasbeena2.5%increaseinthenumberofpeoplewithoutaccesssince2010.IntheSTEPS,currentpoliciesreducetheglobalnumberofpeoplewithoutaccesstoelectricitybyaround125millionin2030,althoughpopulationgrowthmeanstherearestillaround650millionpeoplewithoutaccessin2030.IntheAPS,thenumberofpeoplewithoutaccesstoelectricityfallsto270millionby2030,andthenumberofpeoplewithoutaccessincountriesinsub-SaharanAfricaiscutbytwo-thirds.IntheNZEScenario,universalaccesstoelectricityisachievedby2030.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions183Figure4.21⊳PopulationwithoutaccesstomodernenergyintheSTEPSCleancookingElectricityMillionpeople3000RestofworldDevelopingAsiaSub-SaharanAfrica20001000201020222030201020222030IEA.CCBY4.0.Numberofpeoplewithoutaccesstocleancookingdeclinesbyjustover15%to2030intheSTEPSandprogressonaccesstoelectricityisalsoslowNote:Sub-SaharanAfricaexcludesSouthAfrica.Almost2.3billionpeopletodayusetraditionalbiomass,coalorkerosenefortheircookingneeds;mostoftheseareincountriesinsub-SaharanAfricaanddevelopingAsia.IntheSTEPS,thenumberofpeoplewithoutaccesstocleancookingfacilitiesfallsbyjustover15%to2030.Ifallnationalcleancookingtargetswereachievedby2030,asassumedintheAPS,thenumberofpeoplewithoutaccesswouldfallbytwo-thirds,butaround735millionpeoplewouldremainwithoutaccess.IntheNZEScenario,universalaccesstocleancookingisachievedby2030,asitisforaccesstoelectricity.Areoff-gridsolutionsthekeydriverbehindrecentprogressinaccesstoelectricity?Overtheyears,solarhomesystems(SHS)havedemonstratedtheirviabilityasareliableelectricitysourceforhouseholds,particularlyinruralareasinsub-SaharanAfricathatdonothaveaccesstoreliablegridconnections.Since2015,annualsalesofSHSwithcapacitiesabove11Watt-peak(Wp)haveincreasedmorethansevenfoldinthesub-Saharanregion(Figure4.22).Suchsystemscanprovidesufficientelectricityforabundleofbasicenergyservices,includinglighting,phonechargingandaradio,thoughonlysystemsabove50Wpareconsideredasprovidingessentialaccess.5Today,morethan45millionpeopleuseSHSabove11Wpinsub-SaharanAfrica,accountingforjustunder10%ofthepopulationwithaccesstoelectricity.In2022,SHScontributedtomorethanhalfoftheincreaseinaccesstoelectricityinsub-SaharanAfrica(IEA,2023d).IEA.CCBY4.0.5Anessentialbundleincludesfourlightbulbsforfourhoursperday,afanforthreehoursperday,andatelevisionfortwohoursperday,whichequatestoroughly500kilowatt-hoursperhouseholdperyear.184InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Off-gridconnectionsplayacentralroleinbringingaboutuniversalaccessbytheendofthisdecadeintheNZEScenario.Overtimehouseholdsinallbutthemostremotesettlementswillgraduallytransitionfromoff-gridtogridconnectionsby2050.Figure4.22⊳Salesofoff-gridsolarsystemsinsub-SaharanAfricasince2015andshareofpopulationwithandwithoutaccessin2022MillionunitsSolarhomesystemsalesLargePopulationwithand6withoutaccess5SmallMini-gridSolarhome442%system4%3GridPopulation242%withoutaccess152%IEA.CCBY4.0.20152016201720182019202020212022IEA.CCBY4.0.Annualsalesofsolarhomesystemshaveincreasedmorethansevenfoldsince2015,providingmorethan45millionpeoplewithaccesstoelectricityNotes:Smallsolarhomesystemsareequippedwithasolarpanelratedfrom11to49Watt-peak(Wp).Largesolarhomesystemsareequippedwithasolarpanelratedabove50Wp.Sub-SaharanAfricaexcludesSouthAfrica.Source:IEAanalysisbasedonsalesdatabasesoftheGlobalOff-GridLightingAssociation(GOGLA,2023).Despiterecentrisingequipmentcostsforsolarhomesystems,salesremainedrelativelystablethroughouttheCovid-19pandemic,andtheyarestilltypicallymoreaffordablethangridconnectionsinmanysub-Saharancountries.In2022,salesofSHSsurgedbyaround50%insub-SaharanAfricaandweredoublethelevelachievedin2018.Pay-as-you-gosystemsthatremovetheupfrontcostbarrierplayanessentialrolewhereaffordabilityisthemainconcernandaccesstoloansremainslow.Thesesystemscurrentlyaccountfornearly95%ofsalesofSHSintheregionamongkeydistributers.However,pay-as-you-gosystemsrelyonmobilephoneservices,posingsignificantchallengesinregionswithweaknetworkcoverageandreliability.Howcanuniversalaccesstocleancookingbeachievedby2030?Thenumberofpeoplewithoutaccesstocleancookinggloballyhasfallenbyaround650millionpeoplesince2010,buttheCovid-19pandemicandtheenergycrisishavecausedslow-downsandsetbacks.Insub-SaharanAfricacountries,thepopulationwithoutChapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions185accesshasrisencontinuously,despiteeffortsbycountriessuchasKenyaandNigeria.Achievinguniversalaccesstocleancooking,asintheNZEScenario,requiresactionstobetakenthatenablenearly2.4billionadditionalpeopletousemoderncookingfuelsbytheendofthisdecade.DevelopmentsinAsiademonstratethatprogresscanbeachievedquickly.InIndia,forexample,morethan450millionpeoplegainedaccessoverjusttenyearsasaresultofliquefiedpetroleumgas(LPG)focussedpolicies.However,limitationsintermsofimport,storageandtransportinfrastructureforLPGandlowerpopulationdensitiesinsub-SaharanAfricaintheneartermimplythatimprovedbiomasscookstovesneedtoplayamuchlargertransitionalrolebeforeruralhouseholdsmovetomoderncookingfuels(IEA,2023e).Figure4.23⊳Impactsofachievinguniversalaccesstocleancookinginemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,2022-2030BillionpeoplePopulationwithaccessImpactsofreachinguniversalaccess8Timecollectingx1.7fuelwood6Prematuredeaths4GHGemissionsModernenergy2demandAnnualinvestment20222030-75%-50%-25%0%25%IEA.CCBY4.0.BoostingaccesstocleancookingprovidesmultiplebenefitsrangingfromimprovedhealthandproductivitytoreducedGHGemissionsNote:Impactsonannualinvestment,energydemandandGHGemissionsrefertothebuildingssector.IEA.CCBY4.0.UniversalaccesstocleancookingcouldbeachievedwithannualinvestmentofaroundUSD8billionbetweentodayand2030alongwithasetofinitiativestoincentivisetheadoptionofcleanfuelsandstoves.Thiswouldyieldimmensebenefitsintermsofimprovedhealth,improvedgenderequityandincreasedproductivity(Figure4.23).Forexample,thenumberofprematuredeathsduetoindoorairpollutionwouldbecutbyover70%,andGHGemissionsassociatedwithcookingwouldbecutbyhalf,aspeoplewouldnolongerrelyontheextremelyinefficientuseoftraditionalbiomass.Afurtherbenefitwouldbetofreeupthesubstantialamountoftimecurrentlyspentoncollectingwoodforuseasfueleachday,aburdenmainlycarriedbywomen.186InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20234.4.2EnergyaffordabilityToday,householdsinadvancedeconomiesonaverageconsumenearlythree-timesmoremodernenergythanhouseholdsinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.6Thisreflectsmajorincome-drivendifferencesinapplianceownership,sizeoflivingspaceandlevelsofcomfort.Forexample,heatingandcoolingneedsarelargelymetinadvancedeconomies,whereasthemajorityofpeoplewithspacecoolingneedsinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiescannotaffordadequatemeanstocooltheirresidences(IEA,2022).Transportfueluseisevenmoreunequal,ascarownershippercapitaisfive-timeslowerinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesthaninadvancedeconomies.Thesedifferencesinenergyconsumptiondecreaseinallofourscenariosashouseholdsinemerging4marketanddevelopingeconomiesbecomewealthierandconsumemoreenergyservices.Inadvancedeconomies,householdenergybillsfallbynearly20%intheSTEPSto2030asaresultofenergyefficiencygainsandlowerwholesaleenergyprices.IntheNZEScenario,billsfallbycloseto40%to2030mainlythankstohigherenergyefficiencygainsfromhomeretrofits,heatpumps,moreefficientappliancesandfasteruptakeofEVs.Whiletheseallrequireadditionalupfrontcapitalcosts,onaveragetheygeneratelargersavingsovertheirlifetimes(Figure4.24).Figure4.24⊳CumulativeenergyexpenditureandenergypricereformeffectsperhouseholdintheNZEScenariorelativetotheSTEPS,2023-2030USD(2022,MER)HouseholdexpenditureEnergypricereformeffectsHouseholds20002500Investment10002000Energybill1500Netexpenditure01000-1000Governments-2000500RemovedsubsidiesCarbonpricingrevenues-3000AdvancedEMDEAdvancedEMDEEconomiesEconomiesIEA.CCBY4.0.ExpenditureislowerintheNZEScenarioinadvancedeconomies;itishigherinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,mainlybecauseofsubsidyreformNotes:MER=marketexchangerate;EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Energybillsperhouseholdincludeexpenditureforenergyuseintheresidenceandfortransportfuels.Investmentperhouseholdincludesspendingonmeasuressuchasenergyefficiencyretrofits,heatpumps,EVsandothercleanenergytechnologyinvestments.IEA.CCBY4.0.6Modernenergyexcludesthetraditionaluseofbiomass.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions187Inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,energybillsarehigherintheNZEScenariothanintheSTEPSby2030,partlybecauseofhigherenergyservicedemandsandpartlybecauseofexpansionandstrengtheningofcarbonpricingschemesandthephasingoutofinefficientfossilfuelsubsidies.Thesepolicychangesneedtobecarefullydesignedtolimitimpactsonhouseholdbudgetsandtosustainsupportforthecleanenergytransition(Box4.3).Someoftherevenuesfromcarbonpricing,forexample,couldbeusedtohelplowerincomeconsumersmeettheupfrontcapitalcostsofcleanenergyappliances.Phasingoutinefficientfossilfuelsubsidieslowerstheburdenongovernmentbudgets:someofthesavingscouldbeusedtoprovidemoreeffectiveandbettertargetedsupportfortheenergycostsoflowincomehouseholdsthroughdirectpaymentschemesorothermeans.Box4.3⊳Demand-sideresponseasatooltocutenergybillsRecentpilotprogrammesintheUnitedKingdomandAustraliademonstratethatdemand-responsepoliciesandinstrumentscanhelpconsumerssignificantlyreducetheirelectricitybills.Responsivetechnologiesandelectricitytariffsallowconsumerstorespondtomarketsignalsbyincreasingelectricityconsumptionwhenpricesarelowandreducingitduringpeakhours,forexamplebycharginganEVovernightwhenelectricitydemandandpricesarelower.Demand-sideresponsecanalsohelplimitcurtailmentofsolarPVandwindattimesofhighergeneration.Figure4.25⊳Electricitybillsavingsfromdemandresponseforhouseholdsandbyend-useintheNZEScenario,2030and2050ElectricitybillsavingsSavingsbyend-use20%100%EVcharging15%75%Spaceheating50%Waterheating10%CoolingAppliances5%25%20302050203020502030205020302050AdvancedeconomiesEMDEAdvancedeconomiesEMDEIEA.CCBY4.0.Demand-sideresponsemeasurescanhelpconsumerscutenergybillsbyuptonearly20%by2050inparticularbyshiftingEVchargingandwaterheatingpatternsIEA.CCBY4.0.Notes:EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Demandresponsereferstotheabilityofaconsumertoshiftconsumptionintimewithnoorlimitedimpactoncomfort.Estimatesofthepotentialofdemand-responsemeasuresaccountfortechnologyandacceptabilitylimitations.188InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IntheNZEScenario,demand-responsemeasuresreducetheaveragehouseholdelectricitybillinadvancedeconomiesby3-6%in2030and7-12%in2050(Figure4.25).Inemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,billscouldbereducedbyupto20%by2050.ThekeyinmanycountriesistherisinguseofsolarPV,whichincentivisesashiftofenergyconsumptiontodaylighthourswherepossible.Majorend-usessuchasEVchargingandwaterheatingprovidethelargestcontributions.Additionalsavingscomefromoperatingappliancessuchaswashingmachinesandrefrigeratorsflexiblyinlinewithpricesignals.Didshort-termaffordabilitymeasureshelptameenergypricespikesin2022?4In2022,householdbudgetsweresqueezedaroundtheworldasaresultofsoaringenergyprices.Wholesalepricesforelectricity,naturalgasandotherfuelswerealreadyincreasingin2021,buttheyrosefurtherafterRussia’sinvasionofUkraine.Governmentinterventionshelpedlimittheimpactonretailenergypricesthroughmeasuressuchasgrantsandvouchersforconsumers,compensationforutilitiesthatkeptpricesdown,andexemptionsfromenergytaxesandcharges(IEA,2023f).Themajorityofshort-termaffordabilityspendingwasinEuropeandotheradvancedeconomies.Wholesaleenergypriceshavenowpassedtheirpeak,butretailpricesarefallingmoreslowlyandmanysupportmeasuresremaininplace.Whilesupportmeasureshadanimportantparttoplayinavoidingunsustainableburdensonhouseholdsduringaperiodofcrisis,theyareamajorburdenforgovernmentsandriskdiminishingtheincentivetouseenergyefficientlyortoswitchtocleanerfuels.Figure4.26⊳Householdenergyexpenditureinaveragehouseholdincomeinselectedcountries,2021and20228%202120226%4%2%GlobalItalyBrazilSouthAfricaIndiaSpainGermanyMexicoJapanIndonesiaChinaUnitedKingdomFranceSaudiArabiaAustraliaKoreaUnitedStatesCanadaIEA.CCBY4.0.IEA.CCBY4.0.Energypricesincreasedsharplyin2022,thoughsupportmeasures,mildweatherandbehaviourchangecushionedtheimpactonhouseholdincomesNote:Residentialenergyexpenditureforaveragehouseholdsreflectsenergybillrebatesandreliefpayments.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions189Theglobalaverageshareofhouseholdincomespentonhouseholdenergybillsincreasedmarginallyin2022.InJapanandSouthAfricaandsomecountriesinEurope,expendituresharesincreasedbyonepercentagepointonaverage,withmuchlargerincreasesforlowerincomehouseholds(Figure4.26).Energyexpenditurewouldhavebeenevenhigherinsomecaseshadresidentialdemandnotdecreased.Government-ledcampaignsinanumberofcountriesinEurope,encouragedconsumerstoadjusttheirthermostats,thoughsomevulnerablehouseholdshadnochoiceinanycasebuttocutbackonheatingtheirhomesinviewofskyrocketingenergyprices.Theshareofincomedirectlyspentonhomeenergybillsremainedflatorevendeclinedincountrieswheretherewassubstantialgovernmentsupporttokeepretailbillsdownorarelativelylowlevelofdependenceonimportedfossilfuelsforpowergeneration,althoughhouseholdbudgetswerestillsqueezedbyhighertransportfuelcosts.Inmostemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,higherpricesfortransportfuelimposedamajorburdenonhouseholds,asdidrisingfoodprices.Around60%ofthefinancialsupportprovidedbygovernmentsinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiestargetedhightransportfuelprices.IEA.CCBY4.0.Arecleanenergytechnologiesaffordableforallconsumers?Consumersplayakeyroleinshapingthecleanenergytransitionwhentheychoosetobuycleanenergytechnologiesinordertobenefitfromlowerenergybills.However,itremainschallengingformanyconsumerstofindthemoneyforimportantcleanenergygoodssuchasEVsandheatpumpsortofundenergyefficiencyretrofitsinbuildings.IntheUnitedStates,forexample,highincomehouseholdsareten-timesmorelikelytoownanEVthanthelowestincomegroups,andtheyalsotendtohavemoresolarpanelsandusemoreefficientappliancesandlightingtechnologies(Davis,2023).Onewayofmakingcleanenergytechnologiesmoreaffordableistousegeneralenergytaxationtoencouragecleanerandmoreefficientconsumerchoices,aimingincentivesatlowerincomehouseholdsinparticular.Somecleanenergytechnologiesarealreadycompetitivewithfossilfuelalternatives,orareverynearlyso.IntheUnitedStates,forexample,airsourceheatpumpsoftendonotcostsignificantlymorethangasboilersandcanprovidesubstantialsavingsovertheirlifetime.Insomemarkets,suchasSweden,theycanevencostlessthanfossilfuel-poweredalternatives.Heatpumpownershipisstilltypicallylessamonglowincomehouseholdswhereupfrontcostbarrierspersist,whichisthecaseinmanypartsofEurope.EVs,inparticularsmallermodelsandtwo-wheelers,areoftenanexception:insomecountries,suchasChina,theyarealreadyavailableatpricesthatarecomparablewith(andsometimeslowerthan)thoseofgasolineordieselfueloptions.Energyefficiencyretrofitsinbuildingsrequiresubstantialupfrontinvestment.Thiscanbeequivalenttouptoninemonthsofincomeforpoorerhouseholds,andcanrepresentabarrierformostotherhouseholdsaswell.Asaresult,fewsuchretrofitstakeplace,eventhoughtheybringdownenergybillsfordecades(Figure4.27).Well-designedfinancialincentivesremaincrucialtoscaleupretrofitswithhighupfrontcostsacrossallincomegroups:theycanbegraduallyphasedoutforwell-offhouseholdsaspurchasecostsdecrease.190InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Figure4.27⊳Purchasecostpremiumofcleanenergysolutionsrelativetomonthsofincomeinselectedmajoreconomies25thpercentile75thpercentile12Monthsofincome202292030NZE634HeatpumpEVvsRetrofitHeatpumpEVvsRetrofitvsfossilboilerICEcarvsnonevsfossilboilerICEcarvsnoneIEA.CCBY4.0.Upfrontcostburdensofcleanenergysolutionsremainhighforlowerincomehouseholds,butrelativecostsaresettofallby2030intheNZEScenarioNotes:ICE=internalcombustionengine.Costpremiumsbasedondataforaveragesizecars,residentialdwellingsandheatpumpsinChina,France,Japan,UnitedKingdomandUnitedStates.Subsidiesarenotincluded.InChina,electriccarsonaveragearecostcompetitivewithICEcars.Source:IEAanalysisbasedonWorldInequalityDatabase(2022)andJATODynamics(2021).IEA.CCBY4.0.4.4.3EnergyemploymentNearly67millionpeopleworkedintheenergyindustryworldwidein2022,withcleanenergy–includinglow-emissionsfuels,low-emissionspowergeneration,powergridsandstorage,energyefficiency,andEVsandbatteries–accountingforoverhalfofalljobs.End-usesectors,includingenergyefficiencyandvehiclemanufacturing,havethelargestemploymentbase(24millionworkers),followedbythesupplyoffuelsandcriticalminerals(22millionworkers)andthepowersector(20millionworkers).MostenergyworkersareintheAsiaPacificregion,withChinaaloneaccountingforalmost30%ofallenergyjobs.NorthAmerica,EuropeandIndiaaccountforjustover10%each.Inallthescenarios,jobcreationassociatedwithcleanenergytechnologiescomfortablyoutweighsjoblossesinfossilfuelandrelatedindustriesthroughto2030.IntheNZEScenario,17millionadditionaljobsaregeneratedintotal(Figure4.28).Insomecases,jobslostinonesectorcouldtransfertoothers.Forexample,manyworkersinvolvedintheassemblyofinternalcombustionengine(ICE)vehiclescouldswitchtoassemblingEVs.Inothercases,however,newjobscreatedsuchasrenewablepowergenerationrequiretraining,maynotpaythesamewagesandmaynotbeinthesameplacesasthejobslostinfossilfuelindustriessuchascoalmining.Insuchcases,targetedactionbynationalandlocalgovernments,Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions191workersorganisationsandindustryareneededtomitigatethesocialcostsoftheenergytransitionandensurethatnoworkersareleftbehind.Figure4.28⊳ChangesinglobalenergyemploymentbysectorintheSTEPSandNZEScenario,2022-2030LossesGainsTotalSTEPSNZE-20-100102030NetchangeICEvehiclesEVsandbatteriesEnd-useefficiencyGridsandstorageLow-emissionspowerUnabatedpowerCriticalmineralsLow-emissionsfuelsCoalsupplyOilandgassupply-8-404812MillionworkersIEA.CCBY4.0.Gainsincleanenergyemploymentmorethancompensateforjoblossesindecliningsectorsinbothscenariosto2030Notes:ICEvehicles=internalcombustionenginevehicles;EVs=electricvehicles;unabatedpower=unabatedfossilfuelpower.Criticalmineralsincludeonlyextractiveactivities.IEA.CCBY4.0.Arelabourshortagesabarriertomeetingtransitiongoals?Thesuccessoftheenergytransitionwilldependnotonlyontechnologicalinnovationandthemobilisationofcapitalbutalsoonthemillionsofworkersthatwillbuildandoperatecleanenergyinstallations.Theavailabilityofproperlyskilledlabourforthejobsthatarebeingcreatedisalreadyemergingasapotentialbottlenecktoachievetransitiongoalsintheneartomediumterm.Constructionrepresentsthelargestsegmentofcleanenergyemploymenttodayandbyfarthemostsignificantsourceofjobgrowththrough2030intheAPSandNZEScenario.However,constructionworkershortagesarealreadythreateningthepaceofcleanenergyinstallationsindozensofmarketsworldwide.Itisalsoprovingdifficulttorecruitadequatenumbersoftradespeoplesuchaselectricians,plumbersandwelders,millionsofwhichwillbeneededforjobsacrosstheentireenergyvaluechain.Themanufacturingsector,another192InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023substantialareaofenergyemploymentgrowth,isalsoencounteringstaffingissuesaslabourdemandincreases.Eveninmanufacturing-intensiveeconomiessuchasChina,factorsincludingshrinkingworkingpopulationsandapreferenceforwhite-collarjobsarepreventingthemanufacturingworkforcefromincreasingquicklyenoughtomeetfuturedemand.Avarietyofmeasureswillbenecessarytoattracttheworkersthatareneededforthefuture.Payandworkingconditionswillclearlybeimportant,aswilltheprovisionofrelevanteducationandtraining.IntheSTEPS,morethanone-thirdofcleanenergyjobscreatedthrough2030arehigh-skilledandwillgenerallyrequiretertiaryeducation,suchasuniversitydegrees,whileanevenhighershareofmedium-skilledjobswillnecessitatevocationaloraarpeparsenhtaiscesostfyalerntroatinminagn.aVgoecdattioonkealeepdpuaccaetiownitihntchoensritsriuncgtidoenm,eanngdinfeoerrtihnigsatnypdeoathnedrdcerigtriceael4ofskills(Figure4.29).Industryandeducationalinstitutionsneedtocollaboratetofillthisgapandpreparethenextgenerationofworkers.Figure4.29⊳JobsbyskilllevelinselectedcountriesintheNZEScenario10%High-skilledpositionsMedium-skilledpositionsCompoundannualgrowthrate2022-30jobgrowth5%2014-20conferralof0%relevantdegrees-5%-10%ChinaUnitedEuropeanChinaUnitedEuropeanStatesUnionStatesUnionIEA.CCBY4.0.Constructionisthelargestsourceofcleanenergyemploymenttoday;actionisneededtoresolvelabourshortagesandmeetexpandingcleanenergylabourneedsNotes:Relevantdegreesforhigh-skilledpositionsarebachelordegreesinscience,technology,engineeringandmathematics;andformedium-skilledpositionsarevocationaldegreesincludingenergy,engineering,mechanicsandconstruction.Precisedegreesincludedvarybycountry.Sources:IEAanalysisbasedonbasedonOECD(2023);ChinaMinistryofEducation(2021);USNationalCenterforEducationStatistics(2020).IEA.CCBY4.0.4.4.4BehaviouralchangeEnergydemanddependsonthebehaviouralchoicesofbillionsofconsumersworldwide.Behaviouralchangesareactionsthatenergyconsumerstaketoreducewastefulorunnecessaryenergyconsumptionandsohelpcutenergyintensity.ManyofthesechangesChapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions193takeplaceaspartandparcelofdailylife,andinvolveusingenergydifferentlyorusinglessofit.Thesechangesdependinpartonindividualchoicesandevolvingsocio-culturalnorms.However,itissystemictransformationsbroughtaboutbytargetedandwell-designedpolicyinterventionsthatcountmostinchangingconsumerbehaviour,andtheseoftendependontheavailabilityofinfrastructureofonekindoranother.TechnicaloptionstoreduceenergyuseareacceleratedintheAPSandmaximisedintheNZEScenario,butthepaceofstockturnoverimposesinherentconstraintsonwhatcanbeachievedby2035.ThebehaviouralchangesintheAPSreflectthoseincorporatedintonetzeroemissionspledges.Thesearemainlyconcernedwithroadtransport,forexampleincludingtrafficreductionmeasuresincities.ThebehaviouralchangesintheNZEScenarioaremorewiderangingandsystemicinnature,andincludeboostingsharedmobility,reducingspeedlimits,discouragingsportutilityvehicleownershipanduse,adjustingheatingandcoolingtemperaturesinbuildings,andswitchingfromplanestotrainsorvideoconferencingwherepossible(Figure4.30).TheNZEScenarioalsointegratesfinancialincentivesanddisincentives,forexampleincludingfrequentflyerleviestoreduceaviationdemandinanequitableway.Figure4.30⊳Energysavingspercapitafrombehaviouralchangesbymeasureandscenario,2035AdvancedeconomiesEmergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies-2LowcarcitiesSharedmobility-4WorkingfromhomeSpeedlimits-6OtherfuelefficiencyReducedSUVuseGJ/capita-8High-speedrailFrequent-flyerlevy-10BusinessflightsSpaceheatingSpacecoolingEco-householdIndustryAPSNZEAPSNZEIEA.CCBY4.0.EnergysavingspercapitafrombehaviouralchangesintheAPSare6%ofthoseintheNZEScenario;inbothscenariosthesesavingshappenmostlyinadvancedeconomiesNotes:GJ=gigajoule.Eco-householdmeasuresinclude:linedryingclothesinsteadofusingadryer;reducinglaundrytemperatures;switchingofflightsinunoccupiedrooms;unpluggingapplianceswhennotinuseandreducingwaterheatingtemperatures.SeeIEA(2022,2021a)fordetailsofothermeasures.IEA.CCBY4.0.BehaviouralchangesintheNZEScenariohappensoonerandtoalargerextentinwealthierpartsoftheworldwheretherearethebiggestopportunitiestocurbwastefulorexcessive194InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023energyconsumption,asevidencedbythefindingthatthetop10%ofemittersintheglobalpopulationwereresponsibleforalmosthalfofallenergy-relatedCO2emissionsin2021(IEA,2023g).BehaviouralchangesintheNZEScenariohelptobringaboutamoreequitableandjustenergytransition.In2035,onapercapitabasis,theenergysavingsfrombehaviouralchangesinaviationareaboutnine-timesbiggerinadvancedeconomiesthaninemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies;inroadtransportandbuildingstheyareaboutfive-timeslarger.Theroleofbehaviouralchangesintheenergytransitionshiftsovertime(Figure4.31).Inthenearterm,behaviouralchangesareparticularlyimportanttoaddressthedecarbonisationcohraflolesnsiglefuseolfbloocilkeersd-iinnheommisessio.nIns2fr0o3m0,ctahrebyoncu-itnoteilndseivmeaansdsebtsy,6su%chanadsInCaEtucraarlsgoanstdheemraonadd4by3%intheNZEScenariocomparedwiththeSTEPS.Inthelongerterm,theirimpactonemissionsfadesastheenergysystembecomesincreasinglyclean,buttheystillsignificantlyreduceenergyusein2050.Figure4.31⊳Energysavingsfrombehaviouralchangesbyfuel,2022-20502022203020402050-5APS-10-15-20NZE-25IEA.CCBY4.0.-30EJOilNaturalgasElectricityModernbioenergyOtherIEA.CCBY4.0.BehaviouralchangeshelpreduceemissionsbycuttingfossilfueluseintheneartermandbycurbingenergydemandgrowthinthelongertermAretherebestpracticepoliciesemergingtotriggerbehaviouralchange?Theenergycrisisof2022promptedbehaviouralinterventionsbyEuropeangovernmentsseekingtoreducesupplyrisk.Forexample,countriesincludingDenmark,Germany,IrelandandSwedenlaunchednationalenergysavingscampaigns.TheSobriétéEnergétique(EnergySobriety)programmeinFranceintroducedahostofbehaviouralmeasures,forexample,reducingspeedlimitsto110kilometresperhouronhighwaysforgovernmentemployees,stipulatingthatlightingforbusinesses,officesandbillboardsmustbeswitchedoffatnight,increasingcashincentivesforremoteworking,andpromotingcarpooling.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions195Table4.2⊳ImpactsofselectedbehaviouralchangesintheNZEScenarioandsimilarexistingmeasuresMeasuresinGlobalimpactinNZEScenarioSelectedmeasuresandtheirimpactsNZEScenarioin2030LowcarcitiesReductioninprivatecar•London:18%reductioninprivatecartravelwithactivitybyupto15%.ultra-low-emissionszones.•Paris:45%reductionincarjourneyssince1990.Reductionintotalroad•Milan:35%reductioninlocalCO2emissionswithtransportCO2emissionsby5%.low-emissionszones.Increaseinpublictransport.•London:33%increaseinbustravelwithultra-low-emissionszones.•Madrid:9%increaseinpublictransportusewithlow-emissionszones.Privatecarsalesreduced•UnitedStates:around4%decreaseofvehiclesalesby9%.percapitafollowingsharedmobilityschemes.Improvedwell-beingfrom:•Jakarta:1000%increaseincyclistsrelatedto300kmofnewcyclelanes.•MoreactivetransportLondon:30%lesscongestionwithultra-low-emissionszones.•Lesscongestedroads•Milan:18%reductioninparticulateandNOXpollutionwithlow-emissionszones;24%decrease•Lowernoiseandairpollutioninroadcasualties.•Improvedhealthandsafety.•Shiftshort-haulReductioninCO2emissions•France:3%reductionofCO2emissionsfromflightstofromdomesticaviationby2%.domesticaviationwithbanonshort-haulflightshigh-speedrail(estimated);77-timeslessCO2emissionsperpassengeronimpactedroutes.Reductioninnoiseand•UnitedStates:3500tonnesofharmfulpollutantsairpollution.avoidedthroughtheCaliforniaHigh-SpeedRailAuthorityProjectwheninoperation.AvoidflightsforReductioninlong-haulflights•China:26%reductioninbusinesstripscomparedbusinesswhennotforbusinesspurposesby43%.topre-Covidpandemiclevels(survey).necessary•Brazil:44%reductioninbusinesstripscomparedtopre-pandemiclevels(survey).SaveelectricityHouseholdelectricity•Japan:7%savinginresidentialelectricitywitheco-householdconsumptionreducedby7%.consumptionduetocampaigns.measures•France:electricitysavingsof9-22%relativeto2022duetotheEnergySobrietyplan.ModeratespaceHouseholdnaturalgas•Germany:10-42%reductioninnaturalgasheatingto19-20°Cconsumptionreducedby10%.consumptioninhouseholdsandbusinessesrelativetoprojected.•France:17%reductioninnaturalgasdemandrelativeto2021levels.ModeratespaceReductioninelectricityspace•India:anestimated8%reductioninelectricitycoolingto24-25°Ccoolingdemandby7%.demandforspacecoolingduetopre-purchasedefaulttemperaturesettingof24°C.Notes:Eco-householdmeasuresinclude:linedryingclothesinsteadofusingadryer;reducinglaundrytemperatures;switchingofflightsinunoccupiedrooms;unpluggingapplianceswhennotinuse;andreducingwaterheatingtemperatures.SeeIEA(2022,2021a)fordetailsofothermeasures.IEA.CCBY4.0.196InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Globally,behaviouralpoliciesarebeingemployedbygovernmentsatanacceleratingrate.IntheGroupof20(G20),forexample,thenumberofpoliciessupportingbehaviouralchangeshasmorethandoubledsince2021.Around50countrieshaveincludedbehaviouralmeasurestosomeextentintheirNDCsorstrategiestoreachnetzeroemissionstargets.Forexample,theNDCsofBangladeshandTürkiyeincludetargetsformodalshiftsfromroadtransporttorail,whileColombiaandAustriahavesetpercentageincreasetargetsforbicycleuse.Thereisincreasingawarenessofthepotentialforpolicyinterventionstoencourageandfacilitatebehaviouralchange,alongsidearecognitionthatcleanenergytransitionscannothappenwithouttheconsent,activesupportandengagementofpeople.Isnimteilramrstooftmheanirydeosfignth,escorpeceeanntdmimepaasuctr,etsheenbaechtaevdioubryalgcohvaenrgnemseinnttsheaNnZdEsSucebn-naartioioanrael4jurisdictions(Table4.2).Forexample,privatecaractivitydeclinesbyupto15%intheNZEScenarioby2030–areductionsimilarinsizetotheoneseeninLondonsincetheintroductionofanUltra-Low-EmissionsZonein2019(18%)–andfarlowerthanthedropseeninParis(45%)stemmingfrommeasuressuchastheadditionofmorethan300kmofbicyclelanesandlimitsontheroadspaceavailableforprivatecars.4.5InvestmentandfinanceneedsEnergyinvestmentiscruciallyimportantineachofourscenarios.IntheSTEPS,globalenergyinvestmentrisestoUSD3.2trillionin2030,nearly15%higherthanestimatedlevelsfor2023(USD2.8trillion).Cleanenergyinvestmentaccountsforalltheincrease,withfossilfuelinvestmentfallingslightlytoUSD1.1trillion.ThetotalincreaseininvestmentislargerintheAPS(a40%increasefrom2022levelsby2030)andNZEScenario(a80%increasefrom2022levelsby2030)giventheneedformoreupfrontcapitalforcleanenergyinvestment.CleanenergyaccountsforUSD3.1trillionoftheUSD3.8trillioninvestedin2030intheAPS,andUSD4.2trillionoftheUSD4.7trillioninvestedin2030intheNZEScenario(Figure4.32).Advancedeconomiesmorethandoubletheircleanenergyinvestmentby2030intheNZEScenario,whileinvestmentinChinanearlydoublesfromitscurrentlevel.Theriseinotheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesismuchlarger,withcleanenergyinvestmentrisingintheNZEScenarioin2030tofive-timestoday’slevel.Thescaleoftheincreasethatisrequiredinpartreflectsthedifficultiesthatthecountriesinquestionhavesofarfoundinrampingupcleanenergyinvestment.Scalingupcleanenergyinvestmentintheseeconomiesisakeychallengefororderlyandjusttransitionsandrequiresactionsinthreeinter-relatedareas:Aclearly-articulatedandambitiousvisionforcleanenergy,underpinnedbyeffectivechangestopolicyandregulatoryregimes.Investmentinhumanandinstitutionalcapacityandstrongenergysectorgovernancetohelpgenerateapipelineofwell-structuredprogrammesandprojects.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions197Enhancedinternationalsupport,includingsignificantlymoreconcessionalfinanceandtechnicalassistancetomitigatecountryandprojectrisksandtoactasananchorfornewinstrumentsandplatformscapableofattractingdomesticandinternationalinvestmentcapitalatscale.Bilateralandmultilateraldevelopmentbankshaveanimportantroletoplayinadvisingonpolicyframeworks,financingandhelpingtodevelopearly-stageprojects,andusingconcessionalcapitaltomobiliselargermultiplesofprivatecapital.Figure4.32⊳Annualenergysectorinvestmentbyscenario,20301200AdvancedeconomiesChinaOtherEMDEBillionUSD(2022,MER)8004002022STEPSAPSNZE2022STEPSAPSNZE2022STEPSAPSNZE203020302030Low-emissionspowerEnergyefficiencyandend-useCleanenergysupplyFossilfuelsIEA.CCBY4.0.CleanenergyinvestmentgapsarelargestinemerginganddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChinaNote:MER=marketexchangerate;EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.IEA.CCBY4.0.Areweinvestingenoughinenergyefficiencyandend-usedecarbonisation?Demand-sideinvestmentissometimesoverlookedindiscussionsonenergytransitions,butithasacrucialparttoplay.Itincludesinparticularinvestmenttoboostenergyefficiencyandencouragebehaviouralchange;toaccelerateexpandedelectrificationofmobilityandheatviaEVsandheatpumps;andtoincreasethedirectuseofrenewablesforheating,coolingandindustrialprocesses,forexamplebyusingsolarwaterheatersandbydeployingthermalenergystoragetoelectrifyindustrialheatprocesses.Currenttrendsintheseareasaremixed.Investmentinelectrifiedend-useapplicationsisrisingrapidly,reflectingtheburgeoningsalesofEVsandheatpumps,mainlyinEurope,ChinaandNorthAmerica.InvestmentinefficiencyreceivedsomethingofaboostfromstimuluspackagesrelatedtotheCovid-19pandemic,andalsofromexceptionallyhighenergypricesin2022thatprovidedsignalstoconsumerstoadoptmoreenergyefficientsolutions.Buttherearesignsthatefficiencyinvestmentisflatteningin2023amidaslowdowninconstructionactivity,higherborrowingcostsandstrainsonhouseholdandcorporatebudgets.198InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023ThereisalargegapbetweencurrenttrendsandtheinvestmentrequiredtogetontrackfortheNZEScenario.TheNZEScenarioseesadoublingofinvestmentinenergyefficiencymeasuresby2030andabroad-basedriseinend-useelectrification(Figure4.33).Thisnotonlyhelpstoreduceemissionsbutimproveshealthoutcomes,insulatesconsumersfromfuelpricevolatility,andimprovesenergysecurityandthebalanceofpaymentsforcountriesdependentonimportedfuels.Manyofthelargestgapsinefficiencyinvestmentareinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,reflectingthedifficultythatmanyhouseholdsandbusinessesfaceinmanagingupfrontcosts,andtherelativeweaknessofpolicyframeworksandenforcementinmanycountries.4Figure4.33⊳Energyefficiencyandend-usedecarbonisationspendingbysectorIntheNZEScenarioin2030relativeto2023eIndex(2023e=1)EnergyefficiencyElectrificationandend-userenewablesOther23.050.3EMDE2.22.35.53.5China5.60.61.31.02.03.0Advanced7.0economies1.40.72.02.62.6BuildingsTransportIndustryBuildingsTransportIndustryIEA.CCBY4.0.Cleanenergyspendingforend-usessuchasEVsandheatpumpsrampsuprapidly,especiallyinemergingmarketanddevelopingcountriesotherthanChinaNote:2023e=estimatedvaluesfor2023;EMDE=emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.IEA.CCBY4.0.Energyefficiencyinthebuildingssectorstandsoutasinparticularneedofhigherinvestment:intheNZEScenario,itrequiresasixfoldincreaseinspendingby2030inChinaanda23-foldriseinotheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Theurbanpopulationisincreasingrapidlyinmostdevelopingeconomies,andensuringthatnewbuildingsmeethighperformancestandardsforheatingandcoolingpresentsahugeopportunitytominimisefuturestrainsonenergysupplyandtolimitemissions.However,relativelyfewdevelopingeconomiesotherthanIndiahavesofarputenergyefficiencybuildingcodesinplace.Whenitcomestoelectrificationofenergyend-uses,moreinvestmentisneededinallregionsintheNZEScenario.Inrecentyears,morethanhalfofglobalEVsalestookplaceinChina,butitwillstillneedtodoubleinvestmentby2030(USD150billion)andadvancedeconomieswillneedtoincreasespendingbyafactorofseventomeetinvestmentlevelsintheChapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions199NZEScenario(USD370billion).EmergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChinawillneedtoincreaseinvestmenttoUSD110billion,whichismorethan50-timeshigherthancurrentlevels.Electrictwo/three-wheelersarewidelyavailableinmanydevelopingeconomies,asareelectricbuses,butinmostcasesEVdeploymentlevelsareonlyjuststartingtorise:theshareofelectriccarsintotalsaleswas3%inThailandin2022,and1.5%inIndiaandIndonesia(IEA,2023h).RisingdebtlevelsandhigherborrowingcostsmeanthatfewdevelopingeconomieswillhavethebudgetaryspacetoreplicatetheEVpurchasesubsidiesthathavedriventheEVboominChinaandadvancedeconomies,andtheywillneedinternationalsupporttoincreasetheuptakeofEVs.TheconcessionalfundingneededforemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesotherthanChinatosupporttransportenergyefficiencyanddecarbonisationintheNZEScenarioisestimatedataroundUSD10billionannuallybytheearly2030s.Thiscouldfocusinitiallyonreducingthecostofelectrictwo/three-wheelers,e-busesandtaxifleetstomakethemmoreaffordablewithprovisionofconcessionalfinanceandgrants:itwillalsoneedtosupportinvestmentincharginginfrastructure.Notallpotentialactionsdependontheavailabilityofconcessionalfinance(Box4.4).Forlight-dutyvehicles,forexample,governmentsinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiescouldintroducedifferentiatedimportdutiesthatfavourEVs.Theycouldalsoconsiderpolicypackagesthatincludevehicleefficiencystandards,pollutionemissionsstandardsanddifferentialfueltaxationmeasures.Box4.4⊳RoleoffinanceinenergytransitionsAchievingtheincreaseininvestmentincleanenergyintheNZEScenarioby2050requiresamajorreallocationofcapitalacrosstheenergysectorandareconfigurationoftheglobalfinancialinfrastructuretoaccommodatethisshift.Thisholdsparticularlytrueiftheinvestmentgapinemergingmarketanddevelopmenteconomiesistobeclosed,asabout80%oftheworld’sfinancialassetstodayarecurrentlyheldinadvancedeconomies.Findingmechanismsthatwillenablethechannellingoffundsatscaletoemergingmarketanddevelopmenteconomiesisnoeasytask,andfewprovenmodelsexisttoday.Thechallengeismademoredifficultbythehighupfrontcostsofkeytechnologiesthatareneededaspartofcleanenergytransitions,notablyinthepowerandend-usesectors.Thismakestheabilitytoborrowandservicealargershareofdebtandensureadequaterisk-adjustedreturnsoninvestmentforequityholderscriticaltoattractinvestment.Equityhasunderpinnedthemajorityofannualenergyinvestmentstodateandplaysapivotalroleinfundingcleanenergytransitions(IEA,2021b).Itistypicallyusedtofundearly-stagebusinessmodels,newtechnologieswithhighupfrontrisksandprojectsthatrequirelongleadtimes.Theavailabilityofequityfinancingalsooftenunderpinsinvestmentinend-usesectorssuchasenergyefficiencyorelectrification,suchasheatpumps,wheretransactionsizesaregenerallysmallerbutwheresmallandmediumsizeenterprisesfacehigherlendingratesthanlargercorporateentities.IEA.CCBY4.0.200InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Althoughequityfundingremainscrucial,thecapitalstructureofinvestmentseenintheNZEScenarioreliesonasignificantincreaseindebtfinancing,withsustainablefinanceplayinganincreasinglyimportantroleinchannellingfundsfromcapitalmarketsintocleanenergyprojects.Greenandsustainabledebthasbeendevelopingrapidlyinrecentyears–itreachedUSD1.5billionin2022–butitstillaccountsforasmallshareofglobalbondissuances(5%in2022)andisdisproportionatelyconcentratedinadvancedeconomies(80%ofissuancesin2022)(IEA,2023i).Whereissuancesinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesdooccur,theyarestilldominatedbyhardcurrency,exposingthemtoforeignexchangerisk.IntheNZEScenario,improvementsinregulatorystandardsinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesandtheriseoflarge-scale4sovereignissuancesmeanthatgreendebtproductsquicklytranslateintonewinvestmentincleanenergyinthosecountries.Inadditiontoariseindebtfinancing,theNZEScenarioseesmoreprivatesectorbackedfinancing,morefinancingfromdomesticsources,andmoreconcessionalfinanceprovidedbyDFIsandspecialisedmechanismssuchasclimatefinanceorcarbonmarkets.Theseallcontributetosomeextenttoclosingtheinvestmentgapinemergingmarketanddevelopmenteconomies.IEA.CCBY4.0.Whataretheimplicationsofourscenariosforinvestmentinoilandgas?Determiningtheappropriatelevelofinvestmentinoilandgasisafraughtandemotiveissueintheenergydebate.Some,includinglargeresource-holdersandcertainoilandgascompanies,maintainthattheworldisprematurelyturningawayfrominvestmentinoilandgas,andthatthepaybackfortoday’sunderinvestment,astheyseeit,willbeaperiodofsharpfuelpricespikesandvolatilitydowntheroad.Othersarguethatoilandgasinvestmentisalreadyunacceptablyhighgiventheimperativetotackleclimatechange,andthatfurtheroverinvestment,astheyseeit,willlocktheworldtoapathwaythatpushesglobalaveragetemperatureswellbeyond1.5°C.Whatdothescenariostellusaboutthiscrucialissue?Fourkeyfindingsarehighlighted:TheoilandgasinvestmentmessagefromouranalysisoftheoutlookintheSTEPShasevolved.Untilthisyear,wesawagapbetweentheamountsbeinginvestedinoilandgasandthefuturerequirementsofthisscenario.Ourrecommendedsolutionwastoscaleupcleanenergyspendingandtherebyreducetherequirementforoilandgas.Whathashappenedinpracticeisthatoilandgasinvestmenthasrisen,whilethelevelofoilandgasinvestmentneededintheSTEPSin2030hasfallenasaresultoflowerprojectionsoffutureoilandgasdemand.Asaresult,currentinvestmentlevelsareadequatetomeetprojectedsupplyneedsintheSTEPS.Thereisnolongeraneed–inanyofthescenariosthatwemodel–foroilandgasinvestmentin2030tobehigherthanitistodaySentimentintheindustryseemstobebroadlyalignedwiththisview:lessthanhalfoftheavailablecashflowsfromrecordrevenuesin2022wentbackintoChapter4Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitions201newoilandgasinvestment,andcurrentupstreamspendingremainsbelowwhereitwasin2019.TheinvasionofUkrainedisruptedtheglobalenergysystemandresultedinalowerlevelofexportsofoilandgasfromRussia.Consumersneededtoadjusttothis,andthathasnowhappened.ShortfallsinsupplyfromRussiaarenolongerareasontoargueforhigheroilandgasinvestment.Today’slevelofinvestmentinallfossilfuels,includingoilandgas,issignificantlyhigherthanwhatisneededintheAPSanddoublewhatisneededintheNZEScenarioin2030.ThisimpliesthatfossilfuelinvestorsthinkthattheSTEPSdescribesthelikelyfuturemoreaccuratelythantheAPSortheNZEScenario.Thecurrentlevelofinvestmentcreatestheclearriskoflockinginfossilfueluseandputtingthe1.5°Cgoaloutofreach.However,simplycuttingspendingonoilandgaswillnotgettheworldontrackfortheNZEScenario–thekeyistoscaleupinvestmentinallaspectsofacleanenergysystem,especiallyinemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,andtomeetrisingdemandforenergyservicesinasustainableway.Bothoverinvestmentandunderinvestmentinoilandgascarryrisksforsecureenergytransitions.Evaluatingtheimplicationsofinvestmentsisnotstraightforward:amongotherthings,anyassessmentneedstotakeintoaccountthesourceofinvestmentandthelikelyefficiencyofthespending.Policymakersalsoneedtokeepawatchfuleyeinthiscontextontrendsthatcouldpointtoafutureconcentrationinsupplyorotherenergysecurityrisks.Butwhenitcomestotheoveralladequacyofspending,ouranalysissuggeststhattherisksareweightedmoretowardsoverinvestmentinoilandgasthantheopposite.IEA.CCBY4.0.202InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter5RegionalinsightsDifferentstartingpoints,differentpathwaysSUMMARY•Thischapterfocusesontheprospectsforselectedcountriesandregionsovertheperiodto2050undertheStatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS),whichconsidersthecurrentpolicylandscapeandmarketconditions,andtheAnnouncedPledgesScenario(APS),whichassumesalllong-termcommitmentsaremetinfullandontime.Togethertheseselectedcountriesandregionsaccountfornearly90%ofglobalenergyconsumptiontoday.•Theglobalenergycrisispromptedarangeofnewinitiatives,notablyinadvancedeconomiesandChina,thataimtoincreasethepaceofcleanenergydeployment.Measuresvaryfromregiontoregion,buttheyalltendtoplacegreateremphasisonboostingtheshareofrenewablesinelectricitygeneration,incentivisingelectriccarsalesandimprovingenergyefficiency.•Energyneedsinmanyemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesareincreasingrapidly,whichrequiremajornewinvestmentinenergyinfrastructurerangingfromelectricitygenerationandgridstoelectricvehiclechargingstations.Levelsofambitionvary,butthereisawidespreadrecognitionthatcleanenergytechnologiescanoffercost-effectivesolutionsforarangeofdevelopmentobjectives.Someemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesfacedifficultiestoobtainfinancing.Concessionalfundinghasaroletoplayinthisregard,asdoinitiativessuchastheJustEnergyTransitionPartnerships.•Severalcountrieshaveadoptedpoliciesthatencouragethediversificationofsupplychainsforcleanenergytechnologies.Thisincludespoliciestopromotecleanenergytechnologymanufacturing,forinstance,theInflationReductionActintheUnitedStates,theNetZeroIndustryActintheEuropeanUnionandtheProductionLinkedIncentivesschemeinIndia.•Despitemovesbycountriestoreducedependenceonimportedfuelsandongeographicallyconcentratedcleanenergytechnologysupplychains,theneedforinternationaltradeandco-operationremainsstrong.Nocountrycanexpecttobewhollyself-sufficient,andmostwillcontinuetodependonimportsandexports.Internationalcollaborationoninnovationinparticularwillremainvitalinthedevelopmentofcleanenergytechnologies.•Today,anumberofcountriesrelyheavilyonrevenuefromoilandgasproduction,andtheyfacetheprospectthattheserevenueswilldeclineascleanenergytransitionsadvance.ThisunderlinestheneedforbroadereconomicdiversificationtocompensateforfallingfossilfuelexportrevenueintheAPS.Somecountriesarealreadytakingstepsinthatdirection.Chapter5Regionalinsights203Aworldofregions76000336End-usemodernenergyconsumptionpercapita(GJ)20054000449Keyeconomicandenergyindicatorsin2022highlightdiversestartingpoints,amongtheselectedcountriesandregionalgroupings,theUnitedStateshasboththehighestpercapitaincomeandenergydemand,whileAfricahasthelowest.100Population(millionpeople)GDPpercapita(USD2022,PPP)14245800AfricaIndiaSoutheastLatinChinaEuropeanMiddleJapanandEurasiaUnitedStatesAsiaAmericaandUnionEastKoreatheCaribbean45%65%Withthedeploymentofcleanenergytechnologiesreshapingthefutureenergysupplymixacrosstheoftheelectricityofallcarssoldinworld,internationalco-operationforsecurity,tradegeneratedinthetheEuropeanandinnovationwillcontinuetoremainprominent.UnitedStatesinUnionareelectric2030isfromby20302X18%100renewables,upmillionfrom22%todayEnergydemandforoftheelectricitywaterdesalinationgeneratedinIndiaelectriccarsontheTotalenergysupplydoublesby2030isfromsolarroadinChinaby2030intheMiddleEastsourcesby2030,upfrom6%today202220502050STEPSAPSOtherRenewablesNaturalgasOilCoal55%1.2billionUSD45%18GW17billiongrowthby2030inAfricansreceiveofthetwo/three-ofnewoshoreLatinAmericaandaccesstocleaninspendingcanwheelerssoldinwindcapacitytheCaribbeancookingifthereducemethaneSoutheastAsiaareaddedinJapanrevenuefromthecontinentachievesemissionsfromoilelectricby2030andKoreaby2030productionofuniversalenergyandgasoperationscriticalmineralsaccessby2030inEurasiaby75%usedincleanenergytechnologiesNote:ThenumbersinyellowrelecttheSTEPS,exceptforLatinAmericaandtheCaribbean(APS),andEurasiaandAfrica(NZEScenario).5.1IntroductionThechapterexaminesselectedregionsandcountrieswhichtogetheraccountfornearly90%ofglobalGDP,populationandenergydemand.Ithighlightsthespecificissuesanddynamicsthataffectthem,takingaccountoftheirverydifferentspecificcircumstancesandambitions.Startingpointsfortheanalysisvarywidelyanddependonahostoffactorsthatincludepopulation,urbanisation,percapitaincome,economicstructure,availabilityofnaturalresourcesandgeography.Eachsectionincludessomecommonelementsthatdescribetheoverarchingtrajectoriesforenergyandemissions,keyfindingsandthemainfactorsthathelptoexplainthem.Eachsectionalsoprovidesinsightsononeortwotopicalissuesthathighlightdistinctiveaspectsoftheprojections.Table5.1highlightskeyindicatorsfortheselectedcountriesandregions.Table5.1⊳Keyeconomicandenergyindicatorsbyregion/country,20225TotalenergyElectricityCarsperCO2CO2thousandemissionsemissionsPopulationsupplydemand(tpercapita)(million)people(Gt)336(EJ)(kWhpercapita)682144.7UnitedStates6589412133137LatinAmericaandtheCaribbean4493722535571.73EuropeanUnion142525Africa5655212.76MiddleEast265175Eurasia238365081931.41China1420201India14173641902.18JapanandKorea17731SoutheastAsia6794250514902.41016056126312.19429262.622987031.793015921.73Note:EJ=exajoules;kWh=kilowatt-hours;Gt=gigatonnes;t=tonnes.IEA.CCBY4.0.NotestokeyenergyandemissionstrendsacrossregionsEachsectioninthischapterhasakeytrendsfigurethatshowstrajectoriesforoil,naturalgasandcoalprimaryenergydemand,electricitysupply,investmentandcarbondioxide(CO2)emissions.Inallfigures,theSTEPSoutlookforaparticularsectorortechnologyisshownmoreprominentlyinadarkercolour,withthelighterarearepresentingtheremainingcontributionofothersectorsortechnologies.Investmentdataarepresentedinrealtermsinyear-2022USdollars(USD)convertedatmarketexchangerates.CO2emissionsrefertonetenergy-relatedcarbondioxideemissions.Commonunitsandacronymsusedinthefiguresinclude:mb/d=millionbarrelsperday;Mt=milliontonnes;Mtce=milliontonnesofcoalequivalent;bcm=billioncubicmetres;GW=gigawatts;GWh=gigawatt-hours;TWh=terawatt-hours;EJ=exajoules;GtCO2=gigatonnesofcarbondioxide;PV=photovoltaics.Chapter5Regionalinsights2055.2UnitedStates5.2.1KeyenergyandemissionstrendsFigure5.1⊳KeytrendsintheUnitedStates,2010-2050Oildemand(mb/d)Naturalgasdemand(bcm)Coaldemand(Mtce)20100080010500400Transport2050Buildings2050Industry2050201020102010Electricitygeneration(TWh)Investment(billionUSD)CO2emissions(GtCO2)6100001000500050032010SolarPV2010CleanenergyPower2050205020502010APSIEA.CCBY4.0.STEPSIEA.CCBY4.0.TheUnitedStateshasmobilisedunprecedentedlevelsofgovernmentsupporttoboostcleanenergyandreducegreenhousegas(GHG)emissions(Table5.2).TheprincipallegislativevehiclesaretheBipartisanInfrastructureInvestmentandJobsActof2021,whichinvestsaroundUSD190billionforcleanenergyandmasstransit,andtheUSInflationReductionActof2022,whichprovidesanestimatedUSD370billioninfundingtopromoteenergysecurityandcombatclimatechange.IntheSTEPS,theseandotherinitiativesresultinareductionofnearly40%inCO2emissionsby2030,relativetothe2005level(Figure5.1).Thelargestimpactoftheincreasedgovernmentsupportisinthepowersector,followedbytransportandindustry.IntheSTEPS,CO2emissionsin2030inthepowersectorare50%lowerthantoday.Thisislargelytheresultoftaxcreditsthatacceleratethedeploymentofsolarphotovoltaics(PV)andwind.Thereductioninemissionsalsoreflectssupportforlifetimeextensionsofnuclearpowerplants,aswellasbatteriesandcarboncapture,utilisationandstorage(CCUS)technology.Inthetransportsector,taxcreditsforelectriccarsandinvestmentincharginginfrastructureleadtoannualsalesofelectriccarsrisingfrom1millionin2022and1.6millionin2023tocloseto8millionin2030,bywhichtheyaccount206InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023for50%ofnewcarregistrations.Technologiesthataidemissionsreductionsinhard-to-abateindustrialsectors,suchasCCUSandlow-emissionshydrogen,areeligibleforsubstantialtaxcredits,whichcanlaythefoundationforstronggrowthintheyearsahead.Byattractingprivatecapital,theseincentivescollectivelysupportadoublingincleanenergyinvestmentintheUnitedStatesby2030over2022levels.Thereisalsoanotableincreaseincross-cuttinginvestmentintechnologyinnovation.Theseinvestmentsfurtheracceleratereductionsindemandforcoal,whichfacesincreasinglystrongcompetitionfromrenewablesandnaturalgas.IntheSTEPS,coaldemandfallsbyalmostthree-quartersby2030relativetothecurrentlevel,largelythankstosolarPVandwindincreasingtheirshareofelectricitygeneration.Naturalgasdemandishigherthanthelevelin2022forseveralyears,butpeaksinthemid-2020sandthenbeginstodecline,mostlyasaresultoflowerdemandinthepowerandbuildingssectors.Oildemandfallsbynearly2millionbarrelsperday(mb/d)by2030fromaround18mb/dtoday,largelyduetorising5electricvehicle(EV)salesandfueleconomyimprovements.Table5.2⊳KeypolicyinitiativesintheUnitedStatesPolicyDescriptionInflationReductionAct•CommitsnearlyUSD370billionforenergysecurityandclimatechange.BipartisanInfrastructure•CommitsaroundUSD550billionintotalfederalinvestment,includingInvestmentandJobsActaroundUSD190billionforcleanenergyandmasstransitinfrastructure.MethaneEmissions•Focusesoncuttingmethaneemissionsfromthelargestsources,includingoilReductionActionPlanandnaturalgasproduction,landfillsandtheagriculturalsector.UpdatedNationally•AimingtoreduceGHGemissionsby50‐52%by2030from2005levels.DeterminedContribution•NationaltargettoreachnetzeroGHGemissionsby2050.State-levelclean•100%carbon‐freeelectricityorenergytargetsby2050in22statespluselectricitytargetsPuertoRicoandWashingtonDC.Fueleconomystandards•Requirementstoimproveby8%peryearforlight-dutyvehiclesformodelyears2024‐2025andby10%formodelyear2026relativeto2021levels.Zeroemissionsvehicles•CaliforniaZEVmandateforcarsbeginningin2026andrisingto100%ofsales(ZEV)targetsin2035(AdvancedCleanCarsII).Otherstateshaveadoptedthismandate.•Californiaregulationstoboostthedeploymentofmedium-andheavy-dutyZEVs(AdvancedCleanTrucks).Otherstatesfollowedthesameexample.IEA.CCBY4.0.ExportsofoilandgasfromtheUnitedStatesaresettopickupinthecomingyears,inpartbecauseoflowerexportvolumesfromRussia(notablyfornaturalgas).IntheSTEPS,theUnitedStatesmaintainsitsstatusastheworld’slargestnaturalgasexporterthroughto2030.Liquefiednaturalgas(LNG)exportsfromtheUnitedStatesincreaseby75%from2022levelstoreach185billioncubicmetres(bcm)by2030,ofwhich95bcmistransportedtotheEuropeanUnion.Effortstoreducemethaneemissions,alongwithefficiencyandfuelswitchingpolicies,increasetheavailabilityandvaluepropositionofUSoilandgasexports.TheupdatedNationallyDeterminedContribution(NDC)oftheUnitedStatesshowsasubstantialincreaseinambitionto2030inlinewithitspledgetoreachnetzeroemissionsbyChapter5Regionalinsights2072050.ItscommitmenttoreduceGHGemissionsby50-52%in2030from2005levelsrequirescontinuingeffortstoacceleratedeploymentofrenewablesandotherlow-emissionstechnologies.Scalingupbatteriesandotherformsofstoragewillalsobeimportant,aswellasactiontomodernise,digitaliseandexpandgridsinatimelymanner.5.2.2HowmuchhavetheUSInflationReductionActandotherrecentpolicieschangedthepictureforcleanenergytransitions?TheInflationReductionAct,theBipartisanInfrastructureInvestmentandJobsActandotherrecentpolicieshavereshapedtheUSenergyoutlook.Targetingabroadsetoftechnologiesacrossmanysectors,theincentivesnowavailablearemakingcleanenergyinvestmentmoreattractive,promptingfasterdeploymentofcleanenergytechnologiesandthedevelopmentofnewcleanenergymanufacturingcapacitiesintheUnitedStates.OurupdatedassessmentintheSTEPSclearlydemonstratesthesignificantimpactofthesepolicieswhencomparedtotheoutlookpriortothesepoliciesintheStatedPoliciesScenariofromtheWorldEnergyOutlook-2021(hereinafterreferencedasWEO-2021STEPS)(IEA,2021).CleanenergydeploymentandCO2emissionsFigure5.2⊳Cleanenergytechnologygrowthandenergy-relatedCO2emissionsintheUnitedStatesintheSTEPSCleantechnologygrowth,2021-2030GtCO₂Energy-relatedCO₂emissions6Electricvehiclesales5Low-emissionsWEO-2021STEPShydrogenproduction43SolarPVinstalled2capacityWindinstalled1capacity5101520102050BuildingsIndex(2021=1)TransportIndustryPowerOtherSTEPS:WEO-2023WEO-2021IEA.CCBY4.0.TheInflationReductionActspurscleanenergytechnologydeploymentandacceleratesthepaceofCO2emissionsreductionsIEA.CCBY4.0.TheInflationReductionActandotherrecentpolicieshavesignificantlyimprovedtheoutlookforahostofcleanenergytechnologies.Electricvehiclesalesin2030areprojectedinthisWorldEnergyOutlook(WEO-2023)STEPStobe13-timesthe2021level,comparedwithjustathreefoldincreaseinWEO-2021STEPS(Figure5.2).Carboncaptureprojectscompletedby2030intheSTEPS,includingthoseunderconstruction,aresettocapturethree-timesthevolumeofCO2emissionsasin2021,doubletheincreaseprojectedpriortotheInflation208InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023ReductionAct,whilelow-emissionshydrogenisnowexpectedtogainmuchmorethanthemodestfootholdprojectedintheWEO-2021.WindandsolarPVhavealsobenefitedsignificantlyfromthesupportnowavailableforcleanenergytechnologies.Asaresultofthesechanges,energy-relatedCO2emissionsdeclineto3.6gigatonnes(Gt)by2030intheSTEPS,10%belowthelevelin2030projectedintheWEO-2021STEPS.Thepowersectoraccountsformostofthedifference,followedbytransportandindustry,butallsectorsmakeacontribution.Theacceleratedprogressmadeby2030alsopavesthewayformorerapidprogressinsucceedingyears:emissionsin2050arenowprojectedtobeone-thirdbelowthelevelexpectedbeforetheInflationReductionActcameintoforce.Figure5.3⊳ElectricitygenerationfromselectedsourcesintheUnitedStatesintheSTEPS,2022and2030Low-emissionssourcesUnabatedfossilfuels5TWh20002022160012002030STEPS:WEO-2023WEO-2021800400SolarWindNuclearCoalNaturalPVgasIEA.CCBY4.0.TheInflationReductionActacceleratesdeploymentofsolarPVandwind,supportsnuclearlifetimeextensionsandleadstoan80%reductioninunabatedcoalpowerby2030IEA.CCBY4.0.Inthepowersector,theboostprovidedbytheInflationReductionActforbothexistingandnewlow-emissionssourcesofelectricityacceleratesthetransitionawayfromcoal-firedgenerationandreducesCO2emissions.Ifalltheconditionsaremettoreceivethemaximumavailabletaxcreditsforsolarandwind,thenthelevelisedcosttoconsumersofnewsolarPVandwindintheUnitedStatesisexpectedtobelowerthananywhereelseintheworld.Theseincentivesareattractingprivateinvestors.By2030,solarPVoutputsurpasses800terawatt-hours(TWh)intheSTEPS(two-thirdsabovethelevelprojectedinWEO-2021STEPS)andwindreaches1000TWh(almost50%abovethelevelintheWEO-2021STEPS)(Figure5.3).TaxcreditsintheInflationReductionActalsosupportlifetimeextensionsofnuclearpowerplants,whichareoneofthecheapestsourcesoflow-emissionselectricity.Asaresultofthesevariousincentives,unabatedcoal-firedpowerfallsbyabout80%intheSTEPS,comparedwithabout50%intheWEO-2021STEPS.Unabatednaturalgas-firedgenerationalsodeclinesbymorethanprojectedpriortotheInflationReductionAct.Chapter5Regionalinsights209CleanenergymanufacturingInrecentyears,cleanenergymanufacturinghasbeeninsufficienttomeetdomesticneedsintheUnitedStates.Forexample,in2022,thedomesticcontentofwindturbinebladesandhubswasabouthalfandonlyone-thirdofsolarPVmoduleswereproduceddomestically.Whileimportsofcleanenergycomponentswillcontinue,andwouldbenefitfrommoresupplydiversity,theInflationReductionActprovidessignificantincentivestoboostdomesticcleanenergymanufacturingintheinterestsofmaximisingthedomesticbenefitsofthetransitiontocleanenergyandofnationalsecurity.TheseincentiveshaveresultedinanumberofannouncementsfromcompanieslookingtodevelopnewcleanenergymanufacturingcapabilitiesintheUnitedStates,includingplansfortheproductionofhydrogen,batteries,solarPVandwindturbines(Table5.3).TheUnitedStateshaswitnessedasurgeinannouncementsoflargemanufacturingfacilitiesoverthepastyear.Gigafactorycapacity,expectedtoremainoperationaluntil2030,increasedfrom750gigawatt-hours(GWh)inJuly2022to1.2TWhbySeptember2023,dueinlargeparttothesupportintheInflationReductionAct(BenchmarkMineralsIntelligence,2023).Table5.3⊳NewannouncementsforcleanenergytechnologymanufacturingintheUnitedStatesTechnologyDescriptionHydrogenproduction•Aimtoreachover5.5Mtofhydrogenby2030(mainlycoupledwithCCUS).•Top-fiveprojectsaccountforaroundhalfofthecapacitytarget.ThelargestprojectwouldBatteriesproduce1Mtofhydrogenperyearandbeonlinein2028.SolarPVWind•Aimforproductioncapacityof1.2TWhby2030,about12-timesthecurrentlevel.•Top-fiveprojectsaccountforone-thirdofthecapacitytarget.Teslaalonehasannounced260GWhproductioncapacityby2030.•Exceeding40GWproductioncapacityforsolarmodulesby2030,upfrom7GWtoday.•1.5GWproductioncapacityofoffshorenacellesbytheendofthisdecade.Sources:IEAanalysisbasedonBNEF(2023a,2023b),WoodMackenzie(2023),SPVMarketResearch(2023)andBenchmarkMineralsIntelligence(2023).IEA.CCBY4.0.AnincreaseinmanufacturingcapacitieswillhelptheUnitedStatestocreatemoreresilientsupplychainsforcleanenergytechnologies,thoughthesewillinevitablytaketimetodevelop.AroundUSD150billioninplannedinvestmenthasbeenannouncedsofarforkeytechnologies,includingbatteries,EVs,charginginfrastructure,offshorewind,andsolar(USDepartmentofEnergy,2023).Withtheseinvestments,theUnitedStatesislikelytobeabletomeetallormostofitsdomesticneedsforhydrogenelectrolysers,EVandstationarybatterydeploymentby2030.However,evenwithasixfoldincreaseinsolarPVmodulemanufacturing,theUnitedStateswouldstillonlyproduceabout10%ofwhatisneededfor2030deploymentintheSTEPS.Thefigureforwindisevenlower,andtherehavebeenfewannouncementssofaraboutplannedincreasesindomesticmanufacturingcapacityforwindpowercomponents.Ensuringresilientanddiverseinternationalsupplychainsisthereforegoingtoremainimportantascleanenergydeploymentrampsup.210InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20235.3LatinAmericaandtheCaribbean5.3.1KeyenergyandemissionstrendsFigure5.4⊳KeytrendsinLatinAmericaandtheCaribbean,2010-2050Oildemand(mb/d)Naturalgasdemand(bcm)Coaldemand(Mtce)1030080515040Transport2050Buildings2050Industry52010201020102050Electricitygeneration(TWh)Investment(billionUSD)CO2emissions(GtCO2)25000400250020012010SolarPVCleanenergyPower20502050201020502010STEPSIEA.CCBY4.0.APSIEA.CCBY4.0.LatinAmericaandtheCaribbean(LAC)isadiverseandstrategicallyimportantregionwithstrongconnectionstomajorglobalmarkets.Itcomprises8%oftheworldpopulationand7%ofglobalGDPandisoneofthemosthighlyurbanisedregionsintheworld,with82%ofitspeoplelivingincities.Itseconomytodayiscloselytiedtotheproductionoffuels,mineralsandfoodforexport,exposingittovolatilityininternationalmarketsandpricecycles.Theregioniscomingoutofa“lostdecade”ofeconomicgrowthpunctuatedbytheCovid-19pandemicandtheglobalenergycrisis.Curbinghighinflationandpursuingopportunitiesinthenewenergyeconomycouldhelptospuraneconomicrebound.HalfofthecountriesinLAChavepledgedtoachievenetzeroemissionsbymid-centuryorearlier.Theyaccountforaround65%oftheLACGDPand60%ofitsenergy-relatedCO2emissions.Toreachthesegoals,LACcountriesneednotonlytospeedupthedeploymentofcleanenergytechnologiesbutalsototackledeforestation.WhileenergyaccountsforaboutlessthanhalfoftotalGHGemissionsintheregion,agricultureandland-usechangeplayanoutsizedrole,andtheyareresponsiblerespectivelyfor25%and20%oftotalGHGemissions.Chapter5Regionalinsights211Table5.4⊳KeypolicyinitiativesinLatinAmericaandtheCaribbeanPolicyDescriptionNetzeroemissions•Inplacein16outof33countries,representing65%ofGDPand60%ofCO2targetsemissionsfromfuelcombustion.NationallyDetermined•Submittedbyall33countries,including29withupdatedtargets,translatingContributions(NDCs)intoalevelofCO2emissionsfromfuelcombustionof1.7-1.8GtCO2in2030.Environmental•FifteencountriesratifiedtheEscazúAgreement–RegionalAgreementongovernanceAccesstoInformation,PublicParticipationandJusticeinEnvironmentalMatters.Deforestationtargets•Inplacein8countries(Brazil,Chile,Colombia,CostaRica,Dominica,Guatemala,MexicoandSuriname).Hydrogenstrategy•Inplacein8countries(Argentina,Brazil,Chile,Colombia,CostaRica,Ecuador,Panama,Uruguay)and4countrieswithstrategiesannouncedbutstillinpreparation(Bolivia,Paraguay,Peru,TrinidadandTobago).Accesstargets•Setin11countriesforelectricityaccess(24outof33countrieshavealreadyreached95%accessrate);7countriesforcleancooking(12outof33countrieshavealreadyreached95%accessrate).Zeroemissions•Inplacein16countries(Argentina,Bolivia,Brazil,Chile,Colombia,CostaRica,vehiclepoliciesCuba,DominicanRepublic,Ecuador,ElSalvador,Mexico,Nicaragua,Panama,Paraguay,TrinidadandTobago,Uruguay).IEA.CCBY4.0.TotalenergysupplyinLACissettoincreaseasaresultofpopulationandeconomicgrowth.IntheSTEPS,energysupplyincreasesby10%from2022to2030and35%by2050,withtheshareofsupplythatcomesfromfossilfuelsdecreasingslightlyasdeploymentofrenewablesincreases.Theslightdecreaseintheshareoffossilfuelsinenergysupplyisnotenoughtopreventenergy-relatedCO2emissionsintheregionfromrising10%higherthancurrentlevelsin2050(Figure5.4).IntheSTEPS,electricitydemandrisesovertime,twiceasfastasfossilfuels.FinalenergyconsumptioninLACtodayisprimarilyoil,mostofwhichisusedintransport,buttheshareofoilissettodeclineascountriesseekalternativetransportfuels:Brazilleadsinbiofueladoption,whileChile,Colombia,CostaRicaandMexicoareprioritisingtherapiduptakeofEVs.ExpandingownershipofappliancesandairconditionersleadstohigheruseofelectricityinLAChouseholds:by2050,two-thirdsofenergyinthebuildingssectoriselectricity.TheindustrysectorinLACislessenergyintensivethantheglobalaverage,withnon-energyintensivesectors(especiallythefoodsector)accountingfor45%ofindustrialenergydemand(comparedto30%globally),andtheiruseofelectricityalsoincreases.ElectricityinLACtodayisprimarilyfromhydropowerandnaturalgas,butsolarPVandwindmakeupthevastmajorityofnewelectricitysupplyintheSTEPS.Low-emissionssources,whichaccountedforover60%oftotalgenerationin2022,risetoover80%by2050.Naturalgasremainsthelargestfossilfuel,anditistheonlyfossilfuelthatseesanincrementonitsoutputofalmost25%,whilecoalandoilusedeclinebyatleast75%overtheperiod.IntheAPS,meetingNDCsandnetzeroemissionstargetscutsenergy-relatedCO2emissionsby10%by2030and50%by2050,relativetothe2022level(Table5.4).Energyefficiencyplaysakeyroleinmoderatingelectricitydemandincreasesinthebuildingssector,while212InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023furtherelectrificationoftransporthelpstoreducetheshareoffossilfuelsintotalprimaryenergysupplyfromtwo-thirdstodaytobelow60%in2030.Asaresult,LACmakessignificantcontributionstoglobalcleanenergytransitions,accountingforalmost10%oftheglobalreductioninoiluseby2050andabout5%ofthereduceduseofnaturalgas.Cleanerenergysources,morestringentenvironmentalpoliciesandbetteraccesstocleancookingalsohelptoreduceairpollution,amajorcauseofpoorhealthintheregion.ThenewenergyeconomythatemergesintheAPSsetsthestageforLACtotapitsabundantrenewableenergyresourcestoproducelow-emissionshydrogenforbothdomesticuseandexport.5.3.2WhatroleforLatinAmericaandtheCaribbeaninmaintainingtraditionaloilandgassecuritythroughenergytransitions?Theglobalenergycrisishasraisedenergysecurityquestionsformanynetimportingcountries,potentiallycreatinganopportunityforproducersandresource-richcountriesin5theLACregiontostepuptheirownproductionandexport.Thissectionexamineshowtheseopportunitiesplayoutinourscenarios,andalsoconsiderssomeofthecommercialandenvironmentalrisks.Todaytheregionisalreadyanetcrudeoilexporter:intheSTEPSandAPSitispoisedtoplayagrowingroleinglobaloilproductionandtrade.IntheAPS,oilproductionincreaseswhileoildemanddeclinesupto2035inLAC,raisingnetexportsfrom0.6mb/din2022to2.3mb/din2035.ThegrowthisconcentratedinGuyanaandBrazil.Relianceonexportmarketsmakestheseprojectionshighlysensitivetothepaceofglobaltransitions,whichvarysubstantiallyacrossourscenariosdependingonthestrengthofgovernmentpolicies.DemandintheAPScontinuestoallowforsomenewupstreamdevelopmentsiftheyarecompetitiveoncostandexhibitlow-emissionsintensities,butnewoilandgasfieldsaroundtheworldwouldfacemajorcommercialrisksifglobaldemandfollowstheNetZeroEmissionsby2050(NZE)Scenariopathwaythatlimitsglobalwarmingto1.5degreesCelsius.Guyanadiscoveredverylargeoilreservesoffshorein2015andaccountedformorethanhalfofLACcrudediscoveriesand7%ofglobalcrudediscoveriesfrom2015to2023.IntheAPS,Guyanaincreasesoilproductionby1.3mb/dfrom2022to2035(Figure5.5),thelargestincreaseofanycountryinthisscenario.Withapopulationunder1million,nearlyallofGuyana’sexpandedoilproductionisavailableforexport.Theboostinoilexportsgeneratesmorediversityofoilsupplyevenasoverallglobaldemandstartstodecline.ItalsoprovidesanopportunitytosupportGuyana’sdevelopmentifacomprehensivegovernanceframeworkforthesectorisinplace(Balzaetal.,2020)Guyanaquadrupledoilexportsfrom2020to2022,withabouthalfofdeliveredcargoesin2022goingtotheEuropeanUniontohelpreplaceRussianoilandafurtherone-thirdtoAsia.IEA.CCBY4.0.Brazilaccountsforthesecond-largestincreaseinoilproductionintheworldto2035,ataround1mb/d.BrazilhasbeenthelargestoilproducerinLACsince2016,havingovertakenbothVenezuelaandMexico:itcontinuestoholdthispositionthroughto2050intheAPS,accountingforabout5%ofglobalproductionfrom2030to2050.AlltheadditionaloilproducedinBrazilislikelytogoforexport:currentkeyexportmarketsincludeChina,EuropeanUnion,IndiaandUnitedStates.Chapter5Regionalinsights213Argentinahasthepotentialtosignificantlyexpanditsproductionofnaturalgas,whichwouldhavetheeffectofreducingnetimportstotheLACregion.HigheroutputinArgentinawouldcompensateforreducedoutputinseveralotherproducers.TrinidadandTobagoisthesecond-largestnaturalgasproducerinLACtodayandamajorexporterofLNG,butits2022productionwas20%belowarecenthighin2019,anditfallsbyanother30%to2030intheAPS.Overall,LACremainsanetimporterofnaturalgasintheAPS,thoughtheimportvolumesdeclinessharplyafter2030,makingmorethan50bcmavailabletoothermarkets.Figure5.5⊳OilproductioninLatinAmericaandtheCaribbeanrelativetoglobalproductionintheAPS,1990-2050LACshareofglobaloilproductionTop-threeoilproductionincreases,2022-3515%mb/d1.5FordomesticdemandOtherColombia1.010%ForexportVenezuelaGuyanaMexico0.55%ArgentinaBrazil1990201020302050QatarBrazilGuyanaIEA.CCBY4.0.GuyanaandBrazilrankasthefirsttwocountriesintheworldinoilproductiongrowthto2035,withtheircombinedoutputrisingby2.3mb/d,mostlyforexportIEA.CCBY4.0.5.3.3DocriticalmineralsopennewavenuesforLatinAmericaandtheCaribbean’snaturalresources?RisingdemandforcleanenergytechnologiesofferssignificantscopeforLACtoexpandproductionandexportofcriticalminerals,buildingonitswell-establishedminingsectorandsignificantmineralsreserves.Indoingso,itcouldhelptheglobaleconomyavoidthesupplybottlenecksthatmightthreatencleanenergytransitions.Theregionalreadyproduceslargequantitiesoflithium,whichisessentialforalmostalltypesofEVsandstoragebatteriestoday,andofcopper,whichunderpinstheexpansionofrenewablesandelectricitynetworks.LACcouldexpandintoarangeofothermaterialssuchasnickel–akeycomponentinbatteriesandelectrolysers–andtherareearthelementsthatarerequiredforEVmotorsandwindturbines.Therearethreekeyopportunitiesinthisrespect:scaleupproduction,includingundevelopedresources;improvepracticesforresponsibleandsustainablesupply;andmovefromtheproductionoforestoprocessedproducts.LACaccountsfor40%ofglobalproductionofcopper,ledbyChile(24%)andPeru(10%).Copperproductionstartedtopickupin2022afterseveralflatyears.Bothcountriesmadea214InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023sizeablecontributiontoproductiongrowthandnowhaveexpansionprojectsunderway.Amega-portisunderconstructioninPerutofacilitateexports.ThenationalminingplaninChileincludesacopperproductiontargetof7Mtby2030,upfrom5.7Mttoday,and9Mtby2050,alongsideadoublinginannualinvestmentingreenfieldexploration.LACsupplies35%ofgloballithiumandholdsaroundhalfoflithiumreserves.Itishometotheso-called“lithiumtriangle”–alithium-richregionthatspansArgentina,BoliviaandChile.Today,Chileaccountsfor30%andArgentinafor5%ofgloballithiumproduction.Boliviaalsohassubstantiallithiumresources:alackofinfrastructurehassofarhinderedthemfrombeingeconomicallylucrative,butCATL,aChinesefirm,planstoinvestoverUSD1billioninalithiumprojectinBolivia.Sofar,lithiummininghasbeenconcentratedonthesaltflatsofChile,buttheKachimineisexpectedtobeginoperationsinArgentinain2024,andtheGrotadoCirilosminehasjuststartedproductioninBrazil.5Figure5.6⊳RevenuefromproductionofselectedcriticalmineralsandfossilfuelsinLatinAmericaandtheCaribbean,2030and2050BillionUSD(2022)500APSNZEMinerals4002050Totalminerals300Neodymium200Nickel100BauxiteGraphite2022ZincLithiumCopperFossilfuelsCoalNaturalgasOil20302050IEA.CCBY4.0.Revenuefromcriticalmineralsproductionexpands1.5-timesby2030intheAPSandsurpassesthelevelofrevenuefromfossilfuelsby2050inbothscenariosNotes:Revenueistotalproceedsfromdomesticsalesandexports.Assumesaverage2022pricesformineralsin2030and2050,andcurrentLACmarketshareinglobalmineralsproduction.IEA.CCBY4.0.Revenuefromtheproductionofcriticalminerals(graphite,bauxite,nickel,zinc,lithium,copperandneodymium)inLACtotalledaroundUSD100billionin2022(Figure5.6).Withrisingdemandfortheseminerals,LACrevenuefromtheirsalesincreases1.5-timesby2030intheAPS.By2050intheAPS,criticalmineralsproductionrevenueovertakesthatofcombinedfossilfuelproductionintheregion,whichfallstoUSD145billionascountriesaroundtheworlddeliveronannouncedpledgestolimittheimpactsofclimatechange.IntheNZE,therevenuesfromcriticalmineralsproductionrisefurthertoUSD246billionby2050.Chapter5Regionalinsights2155.4EuropeanUnion5.4.1KeyenergyandemissionstrendsFigure5.7⊳KeytrendsintheEuropeanUnion,2010-2050Oildemand(mb/d)Naturalgasdemand(bcm)Coaldemand(Mtce)125004006250200Transport2050Buildings2050Industry2050201020102010Electricitygeneration(TWh)Investment(billionUSD)CO2emissions(GtCO2)46000600300030022010SolarPVCleanenergyPower20502050201020502010STEPSAPSIEA.CCBY4.0.IEA.CCBY4.0.Russia’sinvasionofUkrainehashadprofoundeffectsontheenergysectorintheEuropeanUnion.Vastsumswerespentonenergyin2022:theEuropeanUnionpaidoverUSD300billionfornaturalgasimportsin2022,athreefoldincreasecomparedtotheaverageofthepreviousfiveyears.Thisfedthroughtomuchhigherend-userpricesforbothnaturalgasandelectricity.Eventhoughgovernmentsmadefar-reachinginterventionstocushiontheimpactsandreducedemand,andthewell-integratedEUenergymarketshelpedtomanagesupplyrisks,spendingonenergyuseinbuildings,transportandindustryintheEUin2022roseaboveUSD2trillion,equivalentto12%ofGDP.Inresponsetotheenergycrisis,theEuropeanUnionraiseditscleanenergyambitions,whileplacingenergysecurityattheforefrontofitstransitionplans.ThisisalreadyvisibleintheSTEPS:oilandgasdemandisprojectedtocomedownby15%by2030from2022levels,andcoaldemandby55%.LargelegislativepackagesandaraftofnationalandEU-levelincentives,representingalmostUSD500billioninenactedfundingforcleanenergyinvestmentarereflectedintheSTEPS;renewablesmakeuptwo-thirdsofelectricitygenerationin2030,up216InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023from39%in2022,withwindandsolarPVaccountingforover85%ofthenewcapacitybuiltinthisperiod.IntheAPS,themoreambitiousEUFitfor55packagetargetsarelargelymet,ensuringthattheEuropeanUnionachievesa55%reductioninGHGemissionsby2030relativeto1990levels,andalsomeetstheREPowerEUgoalofeliminatingdependenceonRussiannaturalgasbefore2030.Thisrequiresa20%increaseinrenewablesdeploymentcomparedtotheSTEPSin2030.Table5.5⊳KeypolicyinitiativesintheEuropeanUnionPolicyDescriptionFitfor55•ImplementationframeworkfortheEuropeanGreenDeal.•SupportedbytheRenewableEnergyDirective,EnergyEfficiencyDirective,EUEmissionsTradingSystemreformandCarbonBorderAdjustment5Mechanism.•Includespackagesforelectricitymarketdesign,hydrogenanddecarbonisedgases,creatingharmonisedrulesforasingleenergymarket.•100%CO2emissionsreductionforbothnewcarsandvansfrom2035,emissionsstandardsforheavy-dutyvehiclesandFuelEUmaritimeinitiative.•Increasestheminimumenergyperformancestandardsforexistingbuildings,andrequiresallnewbuildingstobezeroemissionsby2028.Sustainablerecovery•MemberstateshavecommittedclosetoUSD500billiontowardsasustainablerecoverythroughnationalrecoveryplansandEU-levelpackagessuchastheRecoveryandResilienceFacility.REPowerEU•SetsoutapathwaytocutrelianceonRussiannaturalgasviaenergysavings,diversificationofsupplyandacceleratedrolloutofrenewableenergy.NetZeroIndustryAct•Aimstoboostcleanenergytechnologymanufacturing,targetstechnologyareassuchassolarandwind,bioenergy,hydrogen,CCUS,batterystorage,gridsandheatpumps;coverssupportforalternativefuelsandnuclear.EUTaxonomy•Classificationsystemsetsoutcriteriaforinvestmentactivitiesalignedwithnetzeroemissionsgoals,usingtechnicalscreeningcriteria.IEA.CCBY4.0.ElectrificationoftheenergyeconomyintheEuropeanUnionoccursinparallelwithdecarbonisationofthepowersector.Theshareofelectricityintotalfinalenergyconsumptionin2030is25%intheSTEPSandnearly30%intheAPS,comparedwith21%in2022.EVsaccountfor55%ofelectricitydemandgrowthby2050:intheSTEPS,thereare200millionelectriccarsontheroadby2050comparedwitharound6milliontoday;85%ofthevehiclesontheroadareelectric.IntheAPS,thissharereachesnearly90%.Demandforheatinthebuildingssectorisalsoelectrified:morethan330GWofheatpumpsaredeployedby2030intheAPS.Strongsupportforbuildingretrofits,applianceefficiencystandardsandfuelswitchingincentivesremainscrucialtocomplementtheelectrificationofheatinginthebuildingssector,giventhatover70%oftheresidentialbuildingsstockin2050alreadystandstoday.Theenergyintensityofthebuildingsstockimprovesbyabout30%persquaremetreintheSTEPSby2050andalmost50%intheAPS.Chapter5Regionalinsights2175.4.2CantheEuropeanUniondeliveronitscleanenergyandcriticalmaterialstargets?TheEuropeanUnion’scleanenergyambitionsrequirealargequantityofrawmaterials,anditiscurrentlyhighlydependentonimports.Likemanyotherregionsrespondingtopost-Covid-19pressuresonsupplychainsandthefalloutfromtheglobalenergycrisis,theEuropeanUnionhassoughttopromoteinvestmentindomesticproductionasawaytoincreasetheresilienceofenergysupplychains.Whilerecognisingthebenefitsoftradeandtheimportanceofinternationalco-operation,theproposedEUNetZeroIndustryAct(NZIA)wouldrequiretheEUcleanmanufacturingcapacitytoreachatleast40%ofdeploymentneedsby2030,whiletheproposedEuropeanCriticalRawMaterialsAct(CRMA)wouldrequire10%oftheEUannualconsumptiontobeextractedintheregion,andlessthan65%ofitsannualconsumptionofeachmineraltohavebeenprocessedinathirdcountry.Figure5.8⊳ManufacturingcapacityintheEuropeanUnionasshareofAPSdeploymentlevelsandglobalcapacitybyregion,2030EUmanufacturingcapacityWorldcapacityAPS2030deployment100%Worldcapacity80%OtherChile60%AustraliaUnitedStates40%EuropeChina20%EUmanufacturingcapacity2030announcedpipeline2022production2030EUproductiontargetsSolarPVWindHeatpumpsLithiumSolarPVWindHeatpumpsLithiumIEA.CCBY4.0.WindandheatpumpprojectpipelinesareinlinewithEUminimumdomesticmanufacturingtargets,butmosttechnologieswouldstillrelyheavilyonimportsNotes:Countryshareinworldtechnologymanufacturingisestimatedbasedoncurrentprojectpipelinefor2030.Lithiumsupplymixisbasedon2022extractiondata.EUproductiontargetsreflectminimumdomesticmanufacturingandextractiontargetsfromtheNetZeroIndustryandtheCriticalRawMaterialsActs.IEA.CCBY4.0.Around10%ofthe40GWofsolarPVmodulesthatwereaddedintheEuropeanUnionin2022weremanufacturedintheregion.By2030,ifallplannedprojectsarecommissionedontimeandinfull,thissharewouldbejustover20%whenbenchmarkedagainstthedeploymentsneedsoftheAPS,wheresolarPVcapacityadditionsreachover50GWin2030(Figure5.8).Forwind,EUproductionofnacelles–thegeneratingcomponentsonthetopofturbines–cameclosetomatchingthe14GWofcapacityaddedin2022.ThecurrentpipelinefornewwindmanufacturingcapacityhoweverismuchsmallerthanforPV,andsothe218InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023projectednear-triplingofwindcapacityadditionsintheAPSby2030wouldmeantheEUmanufacturedsharefallsjustshortof40%bythatdate.SignificantadditionalinvestmentinmanufacturingcapacityintheEuropeanUnion,particularlysolarPV,wouldbeneededtomeetthegoalsoftheNZIAandCRMA.Importsremaincrucialinanyscenario,withoverallcross-bordertradedictatedbycostcompetitivenessandthepipelineofmanufacturingcapacityinotherpartsoftheworld:currentplanssuggestthatChinaislikelytoretainitsstrongpositioninwindandsolarPVmanufacturing.TheEuropeanUnionisbetterplacedtomeetincreaseddemandforheatpumps.Thereisalreadyenoughcapacitytomeetcloseto40%oftheheatpumpsalesthatarerequiredintheAPSin2030,andasizeablepipelineofadditionalprojectsmeansthataggregateEUproductioncapacityisroughlyequivalenttoprojecteddemandinthisscenario.CurrentlithiumextractioncapacityintheEuropeanUnionwouldmeetlessthan0.5%ofits5needsin2030.Severalnewprojectshavebeenannouncedinrecentyears,includingCzechRepublic,Finland,GermanyandPortugal.Ifallannouncedprojectscomeonlineasplanned,EUregionalextractioncapacitycouldmeet10%ofdeploymentratesintheAPS,therebydeliveringontheCRMAtarget.Nevertheless,mostofthelithiumthattheEuropeanUnionrequireswillstillneedtobeimported.Inbothitsrawandrefinedforms,globallithiumproductionishighlyconcentrated,withrawsupplydominatedbyChile,AustraliaandChina,andrefinedlithiumproducedalmostexclusivelybyChina.Thissuggestsaneedtostrengtheneffortstoformstrategicpartnershipstodevelopprojectsthatwilldiversifysupplychains.IEA.CCBY4.0.5.4.3WhatnextforthenaturalgasbalanceintheEuropeanUnion?InthewakeofRussia’sinvasionofUkraine,theEuropeanUnionreduceditsnaturalgasdemandbyanhistoric55bcmin2022,equivalentto13%oftotaldemandin2021.IntheSTEPS,continuedeffortstodecreasedemandyieldafurther50bcmreductionby2030.IntheAPS,accelerationinend-useelectrification,efficiencyandrenewablesexpansionmeansdemandis60bcmlowerstillin2030andfallsbelow30bcmby2050.ThistrajectoryraisesthequestionofhowtosatisfytheEUnear-termneedforadditionalnaturalgassupplieswithoutcompromisinglong-termemissionsreductiongoals,andwhattheappropriatecontractingandinvestmentstrategiesshouldlooklike.Currently,thegapbetweenfirmcontractedsupplyandprojectedimportrequirementsintheSTEPSliesinarangebetween160bcmand180bcmannuallyovertheprojectionperiod.Ifnofurthercontractsaresigned,thisimpliesacontinuedhighlevelofrelianceonspotmarketsorshort-termcontracts,underpinnedprimarilybyflexiblevolumesofLNG.ThisgapalsoexistsintheAPSinthenearterm,thoughitnarrowssharplyafter2030.WhiletheseoutcomesillustratethatEUgasbuyersfaceagooddealofuncertaintyaboutfuturerequirements,aremaininggapof20bcmintheAPSin2050suggeststhereisstillspacetocontractmoregaswithoutfallingfouloftheEuropeanUnionnetzeroemissionsby2050target(Figure5.9).Whetherthesecontractsareatoddswithglobalambitionstoreachnetzeroemissionsisanothermatter.TheglobalLNGmarketlooksamplysuppliedinthesecond-halfofthe2020s,andnonewprojectsarenecessaryintheAPSortheNZEScenario,sosourcingadditionalgasChapter5Regionalinsights219fromexistingprojectsmaybebetteralignedwithnear-termsecuritygoalsandglobalclimateambitionsthansigningcontractssupportingnewlongleadtimeprojects.EUgasbuyerscouldcontractforflexiblesupplyonalong-termbasisandredirectitelsewhereifitisnotneeded,butthiswouldincreasetheirriskexposureifglobaldemandforgasfellinlinewitharapidtransitiontocleanenergyalongthelinesoftheNZEScenario.Buyersmightinsteadbecomfortablewithahighrelianceonspotmarkets;thecrisishasrevealedEurope’swillingnesstopayapremiumforLNGandthemarket’sabilitytorespondbysourcingthesuppliesnecessarytofillstorageandmeetdemand.However,thisstrategycouldhaveknock-onimpactsonotherimportingcountries,damagingtheirsecurityofsupplyandriskingincreaseduseofcoalasafallbackoption.Figure5.9⊳DriversofnaturalgasdemandreductionandimportneedsbyscenariointheEuropeanUnionbcmDemandreductionsImportneedsDemandreductions400202220302050OtherBioenergy300ElectrificationBuildingefficiency200RenewablesSTEPS100ImportneedsSpot/flexiblesupplySTEPSAPSExistingcontracts:LNGNon-Russianpipeline2022APS2030APS2050IEA.CCBY4.0.TheEU’snaturalgascontractbalanceisdeterminedbythepaceandscaleofdemandreductionsandthewillingnessofEUbuyerstorelyonglobalspotmarketsIEA.CCBY4.0.ThequestionofwhetherthescrambletobuildnewLNGimportterminalsandreinforcepipelinelinksinEuropeendsuplockinginemissionsisalsoanimportantone.Investmentcostsforsuchinfrastructurearerelativelymodestbycomparisonwiththoseinvolvedindevelopingexportinfrastructure,andimportterminalsandpipelinelinksdonotnecessarilyrequirehighratesofutilisationoveralongperiodoftime.Whereimporttakestheformoffloatingstorageandregasificationunits,itisalsorelativelyflexibleandcanbemovedasdemandfornaturalgasevolves.IntheSTEPS,cumulativespendingonLNGimportcapacitybetween2022and2030isUSD55billion,andthisrisestoUSD70billionintheAPS.AfigureintherangeofUSD55-70billionrepresentsaround0.3%oftotalEUspendingonenergyoverthisperiod,andarguablyprovidesimportantenergysecuritybenefitsoverthetransitionperiod.Thereisalsothepossibilitythatsomegasinfrastructurecouldberepurposedinthefuturetotransporthydrogen.220InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20235.5Africa5.5.1KeyenergyandemissionstrendsFigure5.10⊳KeytrendsinAfrica,2010-2050Oildemand(mb/d)Naturalgasdemand(bcm)Coaldemand(Mtce)1030020051501002010Buildings2010IndustryPower52050205020102050Electricitygeneration(TWh)Investment(billionUSD)CO2emissions(GtCO2)24000300200015012010SolarPVCleanenergyTransport20502050201020502010STEPSAPSIEA.CCBY4.0.IEA.CCBY4.0.TheCovid-19pandemicandsubsequentenergycrisiscontributedtoanemergingdebtcrisisinAfricaandaworseningeconomicoutlook.OneconsequenceisthatenergyinvestmentissettoremainlowintheSTEPS,contributingtoslowprogressinextendingaccesstoelectricityandcleancookinginsub-SaharanAfrica(Figure5.10).Today,morethan40%ofpeoplelivinginAfricalackaccesstoelectricityand70%lackaccesstocleancooking.Africawillbehometoone-fifthoftheworld’spopulationby2030andprovidingaccesstomodernenergyforallwhilekeepingpacewithrisingenergydemandremainsaprimaryfocusforAfricangovernments(IEA,2022a).Recentpolicyeffortshavefocussedonreversingflagginginvestmentwithsupportfrommultilateraldevelopmentbanksanddevelopmentfinanceinstitutions(IEA,2023a).Climatecommitmentsamonginternationallendershavemaderenewablepowerprojectseasiertofinancethanmostothers,andrenewablesaccountforhalfofallcapacityadditionssincethepandemic.Withsolarleadingtheway,renewablesaresettocontributeover80%ofnewpowergenerationcapacityto2030intheSTEPS,afigurewhichrisestoaround85%intheChapter5Regionalinsights221APS.NaturalgaspowerplantsmakeupmostofthebalanceoutsideofSouthAfrica:inadditiontoprovidingpower,theyhelpshoreupgridstabilityandprovidescopefortheoperationofregionalpowerpoolssuchastheWestAfricanPowerPool.IntheAPS,newnaturalgaspowerstillcomesonlineinsub-SaharanAfrica,however,NorthAfricaseeslimitedgrowthto2030,relyinglargelyonrenewablestomeetincrementalenergydemandconsistentwithlong-termclimatepledges.InSouthAfrica,representing27%ofcurrentelectricitydemandinAfrica,load-sheddinghasintensifiedasaresultofunplannedoutagesatnumerouscoalplants,promptingasubstantialuptickinrenewablesinvestmentintheSTEPS,eventhoughotheraspectsoftheSouthAfricanJustEnergyTransitionPartnership(JETP)remainundecided.Despitesupplyshortages,nonewcoal-firedpowerplantsarestartedintheSTEPS,consistentwithinternationalcommitmentstoendinvestmentinnewcoalplants.By2030,theshareoflow-emissionselectricitygenerationreachesover40%intheSTEPSinSouthAfrica,risingfrom12%today.ThisrisesfurthertooverhalfintheAPS.Table5.6⊳KeypolicyinitiativesinAfricaPolicyDescriptionJustEnergyTransition•SenegalandSouthAfricaJETPacceleraterenewablesinthepowersector.PartnershipsImplementationdetailsarepending.Regulationofimported•28countrieshaveimplementedrestrictionsontheimportofusedlight-dutysecond-handlight-dutyvehicleswithemissionsstandardsofEuro3orhigherandsetanagelimitofvehicleseightyearsorless(UNEP,2021).Cleancookingaccess•8Africancountrieshaveofficialtargetstoachieveuniversalaccesstocleanpoliciescookingby2030;23countrieshavesetlessambitioustargets.Electricityaccess•22Africancountrieshavesetofficialnationaltargetstoachieveuniversalpoliciesaccessbyorbefore2030;19countrieshavesetlessambitioustargets.Netzeroemissions•15Africacountrieshadstatednetzeroemissionstargetsin2023.targetsIEA.CCBY4.0.Africa’sgrowingenergyneedswillmeanadegreeofrelianceonfossilfuelsforsometimebeforeafulltransitiontakesplacetocleanenergytechnologies.Thesefossilfuelsincludeoilfortransport,liquefiedpetroleumgas(LPG)forcookingandnaturalgasforindustry.IntheSTEPS,anexpandingvehiclefleetincreasesroadtransportdemandforoilby15%in2030.Exceptfortwo/three-wheelers,vehicleelectrificationmakeslittleprogressby2030,hinderedbyhighupfrontcostsandunreliablegrids.IntheAPS,themarketshareofelectriccarsreaches5%by2030,withagelimitsonimportedvehiclesstartingtobringsecond-handelectriccarsintothemarket.LPGdemandrisesslowlyintheabsenceofwell-fundedcleancookingpolicies:itwouldneedtoincreasetwofold,andthreefoldinsub-SaharanAfricatobeconsistentwithuniversalaccesstocleancookingby2030.Africa’sindustriesusearangeoffuelsbutrelyinparticularontheuseofnaturalgas,especiallyforfertiliserproduction,waterdesalination,plusthesteelandcementindustries.222InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023WhiledemandforoilandgasinAfricacontinuestoclimb,prospectsfornewoilandgasprojectsarechangingduetoglobaltrends,whichcarriesimplicationsforcurrentandfutureproducers.Africacurrentlyproduces7mb/dofcrudeoil,ofwhicharound40%isexported.Oilproductionisprojectedtodecline,withlimitednewoildiscoveriescomingonlinethatwillnotoutpacedeclinesfromproducingfields.Africabecomesanetimporterofoilinthemid-2030sintheSTEPS.IntheAPS,oilproductionis0.5mb/dlowerthaninSTEPSby2030.ManyAfricancountriesrelyonimportsofrefinedproducts,althoughanew650000barrelsperdayrefineryinNigeriahelpsmeetincrementaloilproductdemandgrowthinthenextdecade.Prospectsfornewnaturalgasdevelopmentsfarebetter.IntheSTEPS,naturalgasproductionreaches280bcmby2030,fromalevelaround260bcmtoday.Largediscoverieshavebeenmadeacrossthecontinentoverthelastdecade,andmanyAfricancountriesarelookingtodeveloptheseresources,bothforexportanddomesticuse.Netincomefromoilandgas5productionaveragesUSD140billioneachyearintheSTEPSbetween2022and2030,whichfallsto130billionintheAPS.ThedeclineinoilandgasexportrevenuesintheAPScouldbeproblematicforanumberofcurrentandprospectiveproducereconomies,butcleanenergytechnologiesandthecriticalmineralsonwhichtheydependholdgreatpromiseforAfrica,andsomecountriesarewellpositionedtobecomefutureproducers.TodayAfricaaccountsfor13%ofglobalcopperandbatterymetalsrevenue,andthiscouldrise:anumberofcountrieshaveexpressedinterestinattractinginternationalinvestmenttodevelopandprocesstheirresources.IEA.CCBY4.0.5.5.2RechargingprogresstowardsuniversalenergyaccessTheCovid-19pandemic,theenergycrisis,debtproblemsandpoliticalinstabilityhavenearlyeliminatedprogressinAfricaonreducingthenumberofpeoplewithoutaccesstoelectricitysinceitspeakin2013.Todaytherearearound600millionpeoplewithoutaccesstoelectricityinAfrica(Figure5.11),andtheyconstitutearound80%oftheglobalpopulationwithoutaccess.AlthoughpreliminarydatasuggestthatthenumberofpeoplewithoutaccessinAfricamightstabilisein2023afterthreeyearsofincreases,effortsneedtoscaleupquicklytoreachglobalaccessgoals.TheSTEPSseesleadingcountriessuchasCôted’Ivoire,Kenya,GhanaandSenegalreachorgetveryclosetotheirtargets,butthenumberofthosewithoutelectricityaccesscontinuetoriseinmanyothers.Whileutilitydebtsandsupplychainconstraintshaveslowedgridelectricityaccessinvestment,solarhomesystemssalesrosetorecordlevelsin2022andcontributedtohalfoftheincreaseofpeoplewithaccessinsub-SaharanAfricain2022.Solarhomesystemsnowprovideaccesstoelectricitytomorethan8%ofhouseholdsinsub-SaharanAfricathathaveaccess,andtheyaresettoplayanincreasinglyimportantrolethisdecadeinprovidingfirst-timeaccesstohouseholdsinAfrica.ThenumberofpeoplewithoutaccesstocleancookinginAfricareachedalmost990millionin2022.Itisstillrising,andmanyAfricancountriesarenotoncoursetoachieveuniversalaccesstocleancookingevenby2050.Reachinguniversalaccesstocleancookingby2030inChapter5Regionalinsights223linewithSustainableDevelopmentGoal7requirestherapidscalingupofallcleancookingtechnologies.Asafeasible,lowcosttechnology,LPGissettoplayaleadingrole:itprovidescleancookingto40%ofthosegainingaccess.Electriccookingalsohasanimportantrole:itprovidesaccessto12%ofhomesinsub-SaharanAfricaandhastheadditionalbenefitofnotrequiringfuelimports(IEA,2023b).Betweennowand2030,improvedbiomasscookstovesprovidecleancookingtomorethanone-thirdofthosegainingaccess,mainlyinruralareas.Formany,however,thisisatransitionalstepbeforetheygainaccesstocleancookingatalaterdatethroughLPG,electricity,biodigestersorethanolcookstoves.Switchingtoanycleancookingsolutioninsub-SaharanAfricareducesGHGemissions,evenaftertakingaccountofincreasedCO2emissionsfromfossilfuelconsumption,andthismakescleancookingaprimecandidateforclimatefinance.Figure5.11⊳PopulationinAfricawithoutaccesstoelectricityintheSTEPSandgainsbytechnologytypetoreachuniversalaccessby2030PopulationwithoutaccessintheSTEPSPeoplegaininguniversalaccessto2030(90millionpeopleperyear)Millionpeople600NorthAfricaSouthAfricaOtherAfrica400KenyaMini-gridSudan30%GridUganda43%200TanzaniaStand-alone27%EthiopiaNigeriaDRC2000201020202030IEA.CCBY4.0.Somecountriesreachnearuniversalelectricityaccessthisdecade,whileothersseenoprogress;off-gridsystemsplayanimportantroletoprovideuniversalaccessNote:DRC=DemocraticRepublicoftheCongo.5.5.3WhatcanbedonetoenhanceenergyinvestmentinAfrica?MeetingAfrica’srisingenergydemand,providinguniversalaccesstomodernenergyby2030andachievingenergyandclimategoalsmeansmorethandoublingenergyinvestmentthisdecade.ThisrequiresoverUSD200billionperyearfrom2026to2030,withtwo-thirdsgoingtocleanenergy(Figure5.12).BringingaccesstoelectricityandcleancookingforallAfricansrequiresinvestmentofUSD25billionperyear–arelativelysmallpartofthetotal–andequivalenttojust1%ofcurrentglobalenergyinvestment.IEA.CCBY4.0.224InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023EnergyinvestmentinAfrica,however,hasfallenbyalmost45%fromhighsin2014largelyasaresultofaslowdowninoilandgasinvestment.Whileexport-orientedoilandgasprojectsareabletoattractcommercialfinancing,therearefewerbankablecleanenergyprojects,andthosethatareputforwardstruggletosecurefinancing.Potentialinvestorsareoftenconcernedbyrisksstemmingfromrelativelyweakregulatoryenvironmentsorthepoorfinancialhealthofutilities.Theseriskscanreducethecommercialviabilityofprojects,particularlyincountrieswithnascentcleanenergysectors.Theycanalsopushupthecostofborrowingtoatleasttwo-tothree-timesthelevelinadvancedeconomiesforsimilarprojects(IEA,2023c).Asaresult,manyprojectsinAfricarequireconcessionalsupporteithertoactasademonstrationprojectortofacilitatethemobilisationofprivatecapital.Bytheendofthedecade,concessionalfinancetomobiliseprivatecapitalneedstoreacharoundUSD28billionperyearifallenergyandclimategoalsinAfricaaretobeachieved.Thistotalwouldbehigher5intheNZEScenario.Thelimitedavailabilityofdomesticpublicfinancingmeansthatadditionalgrantandconcessionalsupportarealsonecessarytosupportnon-commercialactivitiessuchasearly-stagefinancingandthedevelopmentofearly-stagetechnologies.ThecommuniqueissuedbyAfricangovernmentsattheAfricaClimateSummitinNairobiinSeptember2023calledforadvancedeconomiestomeettheirclimatefinancecommitmentsandforreformofthemultilateralfinancesystemtoaddressthelackofenergyinvestmentonthecontinenttoday.Figure5.12⊳InvestmentneedstomeetAfrica’ssustainablegoalsby2030AnnualaverageinvestmentbysectorCleanenergyinvestmentbyprovider,2026-30(155billionUSD)BillionUSD(2022,MER)250OtherEfficiency200AccessGridsPublic30%150RenewablesFossilfuelsPrivate52%100502016-202026-30Concessionaltomobiliseprivate18%IEA.CCBY4.0.Energyinvestmentneedstodoubletoachieveenergyandclimategoals,withconcessionalcapitalreachingUSD28billioneachyearbytheendofthisdecadeIEA.CCBY4.0.Accessincludesinvestmentrelatedtofossilfuelsources.Note:MER=marketexchangerate;Other=low-emissionsfuels,nuclear,batterystorage,fossilfuelpowerwithCCUS,andnon-efficiencyinvestmentinthebuildings,industryandtransportsectors.Chapter5Regionalinsights2255.6MiddleEast5.6.1KeyenergyandemissionstrendsFigure5.13⊳KeytrendsintheMiddleEast,2010-2050Oildemand(mb/d)Naturalgasdemand(bcm)Coaldemand(Mtce)1210001265006Transport20502010BuildingsIndustry2050201020502010Electricitygeneration(TWh)Investment(billionUSD)CO2emissions(GtCO2)3.0400030020001501.52010SolarPVCleanenergyPower20502050201020502010STEPSAPSIEA.CCBY4.0.IEA.CCBY4.0.Amongemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies,theMiddleEastcollectivelyisattheupperendofincomeandenergyconsumptionlevels,althoughthereisawidedegreeofvariationamongcountrieswithintheregion.Asagroup,GDPpercapitaintheMiddleEastregionis80%higherthaninemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesonaverage,whileenergydemandpercapitaisovertwiceashigh.CountriessuchasSaudiArabiaandtheUnitedArabEmiratesareatthehigherendofpercapitaincomesandenergyconsumption,whileotherssuchasYemenandSyriaareatthelowerend.TheGDPgrowthrateof6.6%in2022intheMiddleEastwasnearlytwiceashighastheaverageforemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesasawhole.SaudiArabia,thelargesteconomyinthisregion,grewnearly9%in2022.RegionalGDPisontracktoincreasebynearly30%bytheendofthedecadeandabout2.4-timesthecurrentlevelsby2050,leadingtoenergydemandgrowthintheSTEPSofmorethan15%by2030and50%by2050.Theregionwouldhavethesecond-largestoildemandgrowthandthelargestnaturalgasdemandgrowthofanyregion,togetherwith30%increaseinannualCO2emissionsby2050.226InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Naturalgasandoilmadeup94%oftheregionalelectricitymixin2022.IntheSTEPS,powergenerationfromnaturalgasincreases,buttheoverallshareofoilandgasneverthelessdecreasestojustover60%bymid-centuryasaresultofanovertwenty-foldriseingenerationbyrenewables,ledbysolarPV.By2030,solarpowergenerationrisesninefoldintheSTEPS,anditsshareofgenerationrisesfrom1%todaytonearly10%.NaturalgasandoilalsomakeupthebulkofcurrentenergyinvestmentspendingintheMiddleEastregion,withcleanenergyinvestmentaccountingforjust15%oftotalinvestment.IntheSTEPS,cleanenergyinvestmentincreasesfourfoldtooverUSD90billionby2050,bywhichtimeitrepresentsoverathirdofthetotal.Thisfallsshortofthetrajectoryimpliedbytheregion’sdecarbonisationgoals,includingnationalnetzeroemissionscommitments.IntheAPS,whichassumesthatallthesecommitmentsaremet,cleanenergyinvestmentincreasesfourfoldtoreachnearlyUSD80billionby2030,takingtheshareofcleanenergyinvestmenttonearlyhalfofthetotal.Inpowergeneration,thisinvestment5leadstorenewablesaccountingforasharplyrisingshareofgeneration,15%oftheelectricitygenerationby2030andatwo-thirdsshareby2050,withsolarPValoneresponsiblefornearlyhalfofalltheelectricitygeneratedby2050.Intransport,salesofelectriccarsintotalcarsalesincreaseto13%by2030intheAPS,comparedwith5%intheSTEPS.IntheAPS,oilandgasdemandintheregionremainsflat,butCO2emissionsneverthelessfallby12%fromcurrentlevelsby2050asaresultofenergyefficiencyimprovementsandalargershareofoilbeingusedforchemicalfeedstocksandthereforenotbeingcombusted.ThedeclineinCO2emissionsintheregionismuchlessthanthatfortheemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesasawhole,whereitfallsbynearly60%intheAPSby2050;thedifferencereflectsarelativelysloweruptakeofcleanenergyintheMiddleEast.Table5.7⊳KeypolicyinitiativesintheMiddleEastIEA.CCBY4.0.PolicyDescriptionNetzeroambitionsPetroleumsubsidies•SaudiArabia,BahrainandKuwaithaveannouncedgoalstoreachnetzeroemissionsby2060,whiletheUnitedArabEmirates(UAE)andOmanHydrogenambitionstarget2050.andpartnerships•SomecountriesintheregionsuchasKuwaitannouncedplansin2023toUAE’supdatedNationallyextendexistingpetroleumsubsidiestoshieldconsumersfromhigherDeterminedContributionprices.KuwaitbudgetedKuwaitidinar1.159billion(USD3.8billion)inpetroleumproductsubsidiesfor2023.•In2023,sixlow-emissionshydrogenelectrolysisprojectswereannouncedinOmanfollowingaRoyalDecreedefiningthescopeofsuchhydrogenprojects.•UnitedArabEmirates2021HydrogenLeadershipRoadmapincludesatargetofacquiringa25%marketshareinlow-emissionshydrogenby2030inthekeyexportmarketsofEurope,India,JapanandKorea.SaudiArabiaisinvestinginnewlow-emissionshydrogenprojectsincludingviatheNEOMGreenHydrogenCompany.•UnitedArabEmirateshasseta19%emissionsreductiontargetfor2030relativeto2019levels.Chapter5Regionalinsights2275.6.2ShiftingfortunesforenergyexportsTheMiddleEasthasfiveoftheworld’stop-tenoilproducers–SaudiArabia,Iraq,UnitedArabEmirates,IranandKuwait.In2022,theMiddleEastproduced31mb/dofoil,ofwhichnearlythree-quarterswasexported,accountingforoverfour-in-tenbarrelsofglobaloilexports.Theregionisalsoamajorproducerofnaturalgaswiththreeoftheworld’stop-tenproducers.Around85%ofgasproductionisusedwithintheregion,whileonly26%inthecaseofoil,whichaccountsforthevastmajorityofenergyexportearnings.IntheSTEPS,theshareoftheMiddleEastinglobaloilproductionincreasessteadily,andthisisreflectedinhigherexportearningsbymid-century.TheseexportsareincreasinglydirectedtoAsia:theroutebetweentheMiddleEastandAsiaalreadyaccountsforaround40%oftotalseabornecrudeoiltrade,andintheSTEPSthisrisesto50%by2050.Figure5.14⊳Revenuefromenergyexportsbyfuelandscenario,andhydrogenproductionbysourceandscenariointheMiddleEastEnergyexportrevenueHydrogenproduction100010%5BillionUSD(2022,MER)EJ8008%46006%34004%22002%12022203020502030205020222030205020302050STEPSAPSSTEPSAPSOilNaturalgasHydrogenandH₂-basedfuelsNaturalgasNaturalgaswithCCUSHydrogenshareofenergyexports(rightaxis)ElectrolysisofwaterIEA.CCBY4.0.DespitestronggrowthofhydrogenproductionintheMiddleEast,revenuesfromtheirexportsdonotoffsetthedeclineinoilandgasexportrevenuesintheAPSevenby2050Note:H2=hydrogen;MER=marketexchangerate.StrengthenedclimatecommitmentsbycountriesaroundtheworldimplymarkedchangesinrevenuestreamsfromoilandgasintheMiddleEast.ShrinkingglobaloildemandintheAPSsubstantiallyreducesexportdemand,resultinginareductionofmorethanUSD80billioninenergyexportrevenuesby2030andoverUSD300billionby2050,whichisequivalenttolessthanhalfoftoday’slevels(Figure5.14).Tocompensate,severalcountriesintheregionareactivelypursuingdiversificationstrategiesthataimtoopennewindustrialandexportopportunitiessuchashydrogenproduction.IEA.CCBY4.0.228InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023TheMiddleEasthassignificantpotentialfortheproductionoflow-emissionsfuels,andthisisanimportantpillarinmanytransitionstrategies.Oman,forexample,aimstoproduceatleast1milliontonnes(Mt)oflow-emissionshydrogenayearby2030andalmost4Mtby2040.The2040hydrogentargetwouldrepresent80%ofOman’scurrentLNGexportsinenergy-equivalentterms.IntheAPS,theshareofhydrogenintheregion’senergyexportsgrowslargerstill.Therevenuestreamfromhydrogentrade,however,isnotsufficienttomakeupfordecliningoilandgasrevenues.Thelargerprizeisthepotentialtoattractinvestmentinhighervalue-addedindustrialsectors,basedontheregion’slargepotentialforlow-costrenewablesandforstoringCO2.5.6.3Howisthedesalinationsectorchangingintimesofincreasingwaterneedsandtheenergytransition?TheMiddleEasthasoneofthelowestlevelsoffreshwateronapercapitabasisintheworld:5climatechangeislikelytoimposefurtherconstraintsonwatersupplyinthefuture.Withagrowingpopulationandeasyaccesstoseawater,desalinationisincreasinglybeingusedtotacklewaterscarcity.Some21000seawaterdesalinationplantsarecurrentlyinoperationworldwide,andtheMiddleEastaccountsfor50%oftheinstalledcapacity(IFRI,2022).Moreover,multiplelargeprojectsareunderwaythatwillincreasedesalinationcapacityintheregion:JordanisplanningamajorplantontheGulfofAqabathatwillincreaseitsdesalinationcapacityfrom4billionto350billionlitreseachyear;SaudiArabiaplanstoconstructanewcitywith9millionpeopleinthenorthwestby2045whichwilldependondesalinatedwaterfromtheRedSeaandtheGulfofAqaba(Al-MasriandChenoweth,2023).Planstoinvestinlow-emissionshydrogenproductionwilladdtowaterdemand.ProductionplansinOmanarebasedonproducinghydrogenfromdesalinatedseawater,forexample(IEA,2023d).Typically,between30and60litresofpurifiedwaterareneededtoproduce1kilogramme(kg)ofhydrogenfromelectrolysis,includingfeedstockwaterandprocesswaterforcooling.However,whileelectrolytichydrogenproductionwouldincreasewaterdemand,areductioninfossilfuelproductioncoulddecreasewaterconsumptionforoilandgasextractionandprocessing.IEA.CCBY4.0.Desalinationisalsohighlyenergyintensive.Themainenergy-relatedneedsfordesalinatedwaterareforcoolingthermalplantsandforupstreamoilandgasoperations.The1.5EJcurrentlyconsumedeveryyearformunicipaldesalinationintheMiddleEastisequivalenttoathirdoftheenergyneedsoftheregion’smassivechemicalsector,andaccountsfor6%ofthetotalenergyconsumptionintheMiddleEast(Figure5.15).Althoughmembranetechnologiessuchasreverseosmosisthatuseelectricityarethemostcommondesalinationtechnologiesinstalledworldwide,theMiddleEastisanexception:thelowcostofoilandgasandtheprevalenceofco-generationfacilitiesforpowerandwatermeantheregionreliesheavilyonfossilfuel-basedthermaldesalinationsuchasmulti-stageflashormultiple-effectdesalination.Today,two-thirdsofthewaterproducedfromseawaterdesalinationintheregionisfromfossilfuel-basedthermaldesalination,andmuchofthemembrane-basedChapter5Regionalinsights229desalinationuseselectricityproducedwithnaturalgas.Overall,theMiddleEastaccountsforroughly90%ofthethermalenergyusedfordesalinationworldwide,ledbytheUnitedArabEmiratesandSaudiArabia.Figure5.15⊳EnergydemandformunicipaldesalinationforhydrogenproductionintheMiddleEastSTEPSAPSIEA.CCBY4.0.820%SolarthermalEJElectricity615%NaturalgasOilShareinTFC(rightaxis)410%25%20222030205020302050IEA.CCBY4.0.Announcedpledgesaffecttheenergymixofdesalinationonlymarginally,butacleantechnologyshiftisneededashydrogenproductionboostsrisingwaterdemandNote:TFC=totalfinalconsumption.IntheSTEPS,growingdesalinationdemandpushestheshareofdesalinationintotalenergyconsumptionto10%in2030and15%in2050.Althoughtheshareofmembrane-baseddesalinationusingelectricityexpandstoalmost20%by2030,demandforfossilfuelsfordesalinationstillrisesby70%to2.3EJ.IntheAPS,asmallertemperatureincreasetranslatesintoreduceddemandforwater,andasaresultenergydemandfordesalinationis6%lowerin2030thanintheSTEPS.However,thereisstillconsiderablescopetomovefurthertowardsamoreefficientandcleanermembrane-baseddesalinationandtomakemoreuseofconcentratingsolarpowertomeetrisingwaterneeds.Therearealsootherwaysofreducingdemandforwater.Thereisconsiderablepotentialtominimisethewaterrequiredinhydrogenproductionbyoptimisingtheelectrolysiscoolingprocess.Pricinghasaroletoplaytoo:consistentunder-pricingofbothwaterandenergyhasencouragedtheinefficientuseofwaterandcontributedtounsustainablelevelsofwithdrawalsfromnon-renewablegroundwaterresources.Policiesthatexplicitlyencouragetheconservationofwatercouldtemperthegrowthfordesalinationdemandfurther.IntheAPS,theseshiftsreduceCO2emissionsfromdesalinationin2030byalmost15MtcomparedwiththeSTEPS.230InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20235.7Eurasia5.7.1KeyenergyandemissionstrendsFigure5.16⊳KeytrendsinEurasia,2010-2050Oildemand(mb/d)Naturalgasdemand(bcm)Coaldemand(Mtce)5.07003002.5350150Transport2050Buildings2050Industry52010201020102050Electricitygeneration(TWh)Investment(billionUSD)CO2emissions(GtCO2)3.0220020011001001.52010SolarPVCleanenergyPower20502050201020502010STEPSAPSIEA.CCBY4.0.IEA.CCBY4.0.ThecountriesoftheCaspianregionandRussia(referredtohereasEurasia)arefacingmultiplepressuresontheirenergysectors,intensifiedbyRussia’sinvasionofUkraine.Traditionalenergyrelationshipshavebeenfracturedor,insomecases,havebrokendowncompletely.RussiaispivotingtonewmarketsinAsia,butlacksinfrastructuretoreachthem.Startingpointsvary,buttheregionasawholehasyettodeploycleanenergyatscale.At175gigajoules(GJ)oftotalenergysuppliedperperson,percapitaenergyconsumptioninEurasiaishighcomparedtotheglobalaverageofabout80GJperperson,andtheaverageofotheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesat60GJperperson.Thislevelofenergyconsumptioninpartreflectscoldwinters,butitalsostemsfromwidespreadinefficienciesinenergysupplyanduse.GDPpercapitainEurasiaisaround30%higherthantheglobalaverage.Theregionishighlydependentonindustry,whichaccountsfornearly40%ofitsGDP.Thepowersectoristhebiggestenergyconsumer,accountingfor44%oftotalenergydemand;buildingsandindustrymakeuparoundaquarteroftotalenergydemandeach.TheregionisheavilyreliantonfossilChapter5Regionalinsights231fuels,whichaccountedfor90%oftotalenergysupplyin2022.Thisshareisprojectedtodeclineslowlyovertimeasdeploymentofrenewablesacceleratesandadditionalnuclearpowerplantsarecommissioned:by2050,itcomesdowntoabout85%intheSTEPSand75%intheAPS.Therelativelyhighproportionoffossilfuelusein2050inbothscenariosandtherelativelysmalldifferencebetweenthetwoscenariooutcomesareareflectionoftheweaknessoftheregion’sstatedclimateambitionsintheenergysector.IntheSTEPS,naturalgasdemandacrossEurasiastaysalmostunchangeduntil2050ataround640bcm.Smallreductionsinnaturalgasuseinpowergenerationareoffsetbyincreasesinotherend-usesectors,notablyinindustry.Oilconsumptionrisesby8%toreach4.7mb/dbymid-century.TheonlyfossilfuelthatseesalargedeclineintheSTEPSiscoal,whichdropsbyathirdto165milliontonnesofcoalequivalent(Mtce)in2050.IntheAPS,naturalgasuseseesareductionofone-quarterby2050,mostlyowingtolowergasuseinthepowerandbuildingssectors.Oildemanddeclinesby8%overthesameperiodasthebuildingssectorreducesoilusebyathirdandthepowersectorbynearly75%.Coaldemanddeclinesby50%ascoaluseinthepowersectoriscutbymorethanhalfandconsumptioninindustrydropsbynearlyathird.Electricityconsumptionisprojectedtoincreasebyaround45%intheSTEPS,risingfromabout1050TWhtodaytomorethan1500TWhby2050.ItclimbsslightlyhigherintheAPSasaresultofincreasedelectrificationofend-usesinthatscenario.Theshareoflow-emissionssourcesintheelectricitymixincreasesrelativelyslowlyfrom34%in2022tonearly45%by2050intheSTEPSandnearly60%intheAPS.ThedifferencebetweentheoutcomesinthesescenariosreflectsamorerapiddeploymentofwindandsolarPVintheAPS,whichseesthesetwotechnologiestogetherprovideabout20%ofelectricityby2050.Table5.8⊳KeypolicyinitiativesinEurasiaPolicyDescriptionKazakhstan:National•AcceleratetheabatementofGHGemissionsthroughthedevelopmentofaMethaneEmissionsNationalMethaneEmissionsInventoryandReductionProgramme.InventoryandReductionProgramme•EuropeanBankforReconstructionandDevelopmentwillassistthegovernmenttojointheGlobalMethanePledge,whichaimstoreduceglobalmethaneemissionsby30%by2030.Azerbaijanand•ContainsacommitmenttodoublethecapacityoftheSouthernCorridorgasEuropeanUnionpipelinetotheEuropeanUniontoover20bcmayearby2027.memorandumofunderstandingto•EuropeanUniontosupportreductioninmethaneflaringandventing,aswellincreaseenergyasAzerbaijan’saccessiontotheGlobalMethanePledge.co-operationRussia:Strategyof•ReduceGHGby80%by2050comparedto1990level,withastrongrelianceonsocio-economicnegativeemissionsfromlanduse,land-usechangeandforestry.development•AchievenetzeroGHGemissionsby2060.IEA.CCBY4.0.Kazakhstan:Strategy•Goaltoachievecarbonneutralityby2060.onAchievingCarbon•Identifieskeysectorsandtechnologiesneededtoachievedecarbonisation.Neutralityby2060232InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Energy-relatedCO2emissionsinEurasiaamountedtonearly2.4Gtin2022.IntheSTEPS,cleanenergyinvestmentmorethandoublesbetween2022and2050.Annualemissionsaresettodeclineslightlyby2050,withthemajorityofthereductiontakingplacebefore2030.IntheAPS,cleanenergyinvestmentmorethantriple,accountingforover60%oftotalenergyinvestmentby2050.CO2emissionsfallbynearlyathirdto1.6GtCO2by2050.CuttingCO2emissionsisnottheonlyimperative:reducingmethaneemissionsfromtheregionaloilandgasinfrastructureisalsoakeychallenge,andonethatisthefocusofseveralpolicyinitiatives.5.7.2What’snextforoilandgasexportsfromEurasia?RussiaRussiahascontinuedtoexportlargevolumesofoilsinceitsinvasionofUkraine,butthecastofbuyershaschanged.ExportsthatpreviouslywenttotheEuropeanUnionandNorth5Americahavemostlybeenredirectedtoothermarkets,notablyIndiaandChina.Inourscenarios,RussianattemptstopivottoAsiaandothernon-Europeanmarketsarehamperedinfutureyearsbytheglobalpeakinoilandgasdemandandthelong-termeffectsofsanctions,whicharefeltmainlyinpartsofRussianoilandgasindustrythatcouldbenefitmostfromWesternequipmentorspecialisation.Inthecaseofoil,exportsfallby1mb/dto2030intheSTEPSand2mb/dintheAPS.Inthecaseofnaturalgas,overallRussianexportsintheSTEPSare40%belowpre-invasionlevelsby2030.PipelineexportstoEuropefellbynearlyhalfin2022;agradualrampupofdeliveriestoChinathroughthePowerofSiberiaandEasternroutesisnotenoughtomakeupforthelostvolumes,andinourscenariosthereisnoneedforadditionalpipelinelinksbetweenRussiaandChina,giventhetrajectoryofdemandinChina.RussiamaylooktoLNGtodiversifyitssupplyoptions,butthatisaverycrowdedfield:around250bcmofnewprojectsareunderconstruction,alltargetingstart-upbetween2025and2030.Russia’sshareofinternationallytradedgas,whichstoodat30%in2021,fallsto15%by2030intheSTEPSandAPS.NetincomefromgassalesfallsfromaroundUSD100billionin2021tolessthanUSD40billionin2030inallscenarios.IEA.CCBY4.0.CaspianTheCaspianregionisrichinoilandnaturalgasresources,butforalongtimehasfacedchallengesoverhowbesttotransportthemtoexportmarkets.Thistraditionalchallengehasbeenresolved,atleastinpart,withnewinfrastructureprojectslinkingAzerbaijan,andtosomeextentKazakhstan,toEuropeanmarkets,andKazakhstanandTurkmenistantomarketsinChina.In2022,theCaspianregionasawholeexported2mb/dofcrudeoilandoilproductsand70bcmofnaturalgas;Chinahasbeenthemajorgrowthmarket,accountingfor40%oftotalexportsin2022comparedwith30%in2012.Buttheprospectsforfurthergrowth,inalldirections,arecloudedbycomplexenergyrelationshipswithRussiaandbythechallengingcommercialcaseforpipelineprojectsatatimewhenthepaceofglobalenergytransitionsispickingup.SomepartsoftheenergyinfrastructureintheCaspianarealsoinneedofmodernisationandrepair,andtherearesupplychokepointsinKazakhstanandUzbekistanthatunderminedomesticenergysecurityandmakeexportsdifficult.Chapter5Regionalinsights233Theprojectedpeakinglobaloilandgasdemandbefore2030intheSTEPSraisesquestionsabouttheviabilityofplanstomonetisealargershareoftheCaspian’suntappedoilandgasresourcesinthefuture.ThereissomepotentialforanincreaseinoilandgasexportstoChina,butthisismoderatedbystagnatingdemandinChinabeyond2030inbothscenarios.TherelikewiseissomemodestpotentialforfurtherwestwardAzerbaijaniexportsasEuropelookstoreplacegaspreviouslyimportedfromRussia.Lookingfurtherahead,however,Europe’slimitedneedforgasisnotwell-matchedwiththelongleadtimesandsignificantupfrontinvestmentinvolvedindevelopingnewupstreamresourcesandmatchinglarge-scalegaspipelines.AgrowinganddynamicglobalLNGmarketappearswell-placedtosatisfyincrementaldemandgrowthinbothAsiaandEurope,andRussiancutstoitspipelinedeliveriestoEuropeappeartohavereinforcedimporterpreferencesfortheflexibilitythatcomeswithseabornetradeovertherigidpoliticsofpipelines.Therehasalsobeenmuchdiscussionaboutotherpotentialmarket-expandinginfrastructure,suchastheTurkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-Indiapipeline,ortheTrans-CaspianGasPipelineProjectlinkingTurkmenandAzerigasfields.However,thesearehinderedbythecomplexwebofgeopoliticalandeconomicintereststhatneedtobereconciledtosecurethepermitsandthecapitalnecessarytogreenlightprojects.AndRussialoomslargeinthebackground,makinguseofitssubstantialinfrastructureconnectionsintheregiontofurtheritsownpoliticalandeconomicinterests.Figure5.17⊳CaspiancrudeoilandnaturalgasexportsintheSTEPSandAPSSTEPSAPSmboe/d4ToEuropeNaturalgas3CrudeoilToChinaNaturalgas2CrudeoilOtherNaturalgas1Crudeoil201220222030205020302050IEA.CCBY4.0.CaspianoilandgasexportstoEuropedeclineandChinaisthemainsourceofgrowthintheSTEPS;totalexportsdeclineby45%by2050intheAPSNote:mboe/d=millionbarrelsofoilequivalentperday,1mboe/d=60billioncubicmetres.IEA.CCBY4.0.IntheSTEPS,Caspianoilandgasexportsclimbtoabout4millionbarrelsofoilequivalentperday(mboe/d)overtheperiodto2030inresponsetorobustoilandgasdemandinChina.234InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023DecliningcrudeexportstoEuropeafter2030offsetmarginaleastwardgrowth,resultinginaslightcontractionintotalexportsby2050.IntheAPS,meetingtheclimateambitionsannouncedbycountriesaroundtheworldreducestheneedforaround0.9mb/dofnewupstreamoilprojectsandaround80bcmofnewgasprojects,comparedwiththeSTEPS,andthislowersthelevelofoilandgasexportsbynearlyhalfin2050.LowerexportvolumesintheAPSareaccompaniedbyloweroilandgasprices,withtheresultthatnetincomefromexportsin2050falltolessthanUSD30billion,aroundhalftheleveloftheSTEPS.TheenvironmentalperformanceofCaspianoilandgassupplyisanotherfactorweighingonitsfutureprospects.Ageinginfrastructureandrelativelypoormaintenanceatproductionsitesatpresentarecausinghighlevelsofloss,andsatellitesaredetectingparticularlylargemethaneleaksfromTurkmenistan.Partlyasaresultoftheselosses,theemissionsintensityofabarrelofoilintheCaspianisestimatedataround150kilogrammesofcarbondioxideperbarrelofoilequivalent(kgCO2/boe);fornaturalgasitisaround120kgCO2/boe.This5putstheregion40%higherthantheglobalaverageintensityforoilandnearlydoublefornaturalgas,leavingitatadisadvantageinaworldincreasinglyconcernedabouttheemissionsassociatedwithoilandgassupply(Figure5.18).Figure5.18⊳FlaringandmethaneintensityofoilandgasproductioninselectedCaspiancountries,2022Flaringintensity(kgCO₂-eq/boe)250TurkmenistanWorldintensity200Kazakhstan150100Uzbekistan50Azerbaijan02000400060008000100001200014000Methaneintensity(kgCO₂-eq/boe)Oilandgasproduction1mboe/dIEA.CCBY4.0.Caspianoilandgasproductionismuchmoreemissions-intensivethantheglobalaverage,primarilyduetoahighlevelofmethaneventinginupstreamoperationsNotes:kgCO2-eq/boe=kilogrammesofcarbondioxideequivalentperbarrelofoilequivalent;mboe/d=millionbarrelsofoilequivalentperday.Bubblesizeindicatesoilandgasproductionin2022inmboe/d.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter5Regionalinsights2355.8China5.8.1KeyenergyandemissionstrendsFigure5.19⊳KeytrendsinChina,2010-2050Oildemand(mb/d)Naturalgasdemand(bcm)Coaldemand(Mtce)206004000103002000Transport20502010BuildingsIndustry2050201020502010Electricitygeneration(TWh)Investment(billionUSD)CO2emissions(GtCO2)14180001000900050072010SolarPVCleanenergyPower20502050201020502010STEPSAPSIEA.CCBY4.0.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chinahasshapedtrendsacrossmanypartsoftheenergysectorinrecentyears.Itsinfluenceremainsstronginallourscenariosbutevolvesinlinewithstructuralchangesinitseconomyandenergysystem(seeChapter1,section1.2).Asthingsstand,Chinaisbyfarthelargestproducerandconsumerofcoal,andamajorconsumerofoilandgas,whichmakesittheworld’slargestCO2emitter,accountingforone-thirdoftheglobaltotal.ItstotalCO2emissionswere12.1Gtin2022,thebulkofwhichstemmedfromtheuseofcoalinelectricitygenerationandindustry.ButChinaisalsothelargestuserintheworldofmanycleanenergytechnologies,accountingin2022for60%ofglobalsalesofelectriccars,50%ofwindcapacityadditions,45%ofglobalsolarPVcapacityadditionsand30%ofnuclearcapacityadditions.Electriccarshavealreadyachieveda29%marketshare,andcleanenergyisadvancingsoquicklythatChinaisontracktoexceedits2030NationallyDeterminedContribution(NDC)targetof1200GWofsolarandwindcapacityfiveyearsaheadofschedule.Chinaalsodominatesmanyaspectsofcleanenergytechnologysupplychains.Intechnologymanufacturing,itiscurrentlythelargestproducerofsolarPV,wind,batteries,heatpumpsandelectrolysersforhydrogenproduction,withplansforfurtherscaleup(IEA,2023e).Italso236InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023producesmorealuminiumandsteelthananyothercountry,andleadstheworldintheprocessingofcobalt,lithium,copper,graphiteandrareearths.Miningofcriticalmineralsisoneofthefewareaswhereitdoesnotleadincleantechnologysupplychains(IEA,2023f).China’s14thFive-yearPlansetsthecourseforitsenergysectorto2025,andenvisagescontinuedscalingupofcleanenergy(Table5.9).IntheSTEPS,China’stotalCO2emissionspeakaround2025andthendeclineatapaceofabout2.3%peryearto2050,fallingto7Gt(Figure5.19).Despitethis,Chinaremainsthelargestemitterintheworldin2050.ButitalsoremainstheleaderindeploymentofseveralcleanenergytechnologiesonthebackofaverageinvestmentincleanenergytechnologiesofwelloverUSD650billionperyear,andby2050itaccountsforhalfofglobalsolarPVcapacity,40%ofwindcapacity,one-thirdofallnuclearpowercapacityand40%oftheglobalelectriccarfleet.Inaddition,Chinaissettobealeaderinelectrolytichydrogenproductionandheatpumpmanufacturing.Table5.9⊳KeypolicyinitiativesinChina5PolicyDescriptionUpdatedNationally•AimstopeakCO2emissionsbefore2030;carbonneutralitybefore2060.DeterminedContribution•LowerCO2intensityofGDPby60%by2030from2005levels.•Reach1200GWofinstalledsolarandwindcapacityby2030.14thFive-yearPlanfor•ReduceCO2intensityofGDPby18%by2025relativeto2020.Energy•ReduceenergyintensityofGDPby13.5%by2025relativeto2020.•20%non‐fossilfuelshareofenergymixby2025,and25%by2030.14thFive-yearPlanfor•Targets3300TWhofrenewableselectricitygenerationby2025.Renewables•Over50%ofelectricityconsumptiongrowthby2025metbyrenewables.14thFive-yearPlanfor•Efficiencyretrofitsfor350millionsquaremetres(m2)ofexistingbuildingsBuildingsand50millionm2ofnear-zero-energybuildingsconstructedby2025.•SolarPVcapacityof50GWby2025innewbuildings.•Geothermalenergyformorethan100millionm2ofbuildingsby2025.MadeinChina2025•Supportsinnovationcapability,digitalisationandgreeningmanufacturing.•Raisingdomesticshareofcorecomponentsandmaterialsto70%by2025.NewEnergyVehicle•PromoteswidespreadadoptionofnewenergyandcleanenergyvehicleIndustryDevelopmentPlansales,targeting25%ofnewvehiclesalesby2025.Carbonpeakingand•Carbonemissionsfromurbanandruralconstructionpeakbefore2030.neutralityblueprintfor•Retrofitsforpublicbuildingsinkeycitiestobecollectively20%moreurbanisationandruraldevelopmentenergyefficientby2030.•Electricityaccountsfor65%ofenergydemandinurbanbuildingsby2030.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chinaisamarketmoverforallfossilfuelsduetothescaleofitsenergyuse.In2022,itwastheworld’slargestcoalconsumer,producerandimporter,thoughitsimportsdeclinealmost30%by2030intheSTEPS,fallingbehindthelevelofimportsinIndia.Itisalsooneofthelargestoilconsumersintheworld,accountingfor15%ofglobaldemandin2022,andoilimportsareprojectedtoincreaseto2030.Itrecentlyalsobecametheworld’slargestnaturalgasimporterandhascontractedlargevolumesfromglobalLNGmarketsaswellaskeypipelinesuppliers,includingRussia.DespitegrowingdeploymentofcleanenergyChapter5Regionalinsights237technologies,Chinaremainsthelargestconsumeroffossilfuelsthroughto2050intheSTEPS.Itscoalusepeaksaround2025,thenstartsalong-termdeclineto50%belowthepeakby2050.Naturalgasusecontinuestogrowstronglyto2030beforeeventuallypeakingin2040ataboutone-quarterhigherthantheleveltoday.Oilconsumptionpeaksat16.6mb/dbefore2030,endingdecadesofgrowth,andthendeclinessteadilyto12mb/din2050.China’supdatedNDCtargets,whichincludereachingcarbonneutralitybefore2060,arefullyreflectedintheAPS.Inthisscenario,China’stotalCO2emissionspeakbefore2025,withfasterprogressonenergyefficiency,renewablesandnuclearpowerleadingtoanearlierpeakincoaluse,andfasterdeploymentofEVshelpingtocurboildemand.Theunabateduseofcoaliscutbytwo-thirdsby2040andalmost90%by2050.Naturalgasusestillincreasesto2030beforeenteringalong-termdecline,butlessofitisusedisallsectorsintheAPS:someofthebiggestdifferencesarepower(about90bcmlowerin2050thanintheSTEPS),followedbyindustry(80bcmlower),buildings(60bcmlower)andtransport(20bcm).ChinahasamassedaconsiderableportfolioofcontractedLNGandpipelineimportsinrecentyears.WithlowerdemandintheAPS,around80bcmofa270bcmportfolioofcontractedgasissurplustorequirementsin2030.OildemandinChinaalsopeaksearlierintheAPS,at15.9mb/dinthemid-2020s,andthengraduallyfallsto6.9mb/din2050.5.8.2HowsoonwillcoalusepeakinChina?ThequestionofwhencoaluseinChinawillpeakisanimportantonefortheglobalcleanenergytransitionbecauseChinaisresponsibleforsuchalargeshareofglobalcoaluse.In2022,Chinaconsumedmorecoalthanallothercountriescombined,andcombustionofcoalemitted8.6GtCO2,accountingforabout70%ofChina’stotalemissionsandone-quarterofglobalenergy-relatedemissions.Figure5.20⊳CoalconsumptionbysectorinChinabyscenario,2022-20504000StatedPoliciesScenarioAnnouncedPledgesScenarioMtce30002000100020102022205020222050ElectricityandheatIronandsteelChemicalsOtherCementIEA.CCBY4.0.IEA.CCBY4.0.Coalconsumptionpeaksinthemid-2020sandthereafterdeclinesby3%peryearintheSTEPSand6%peryearintheAPS238InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Thepowersectoraccountsforover60%ofChina’scoalusetoday(Figure5.21).Coalaccountedforover60%ofelectricitygenerationinChinain2022.Whilehigh,thisshareofgenerationisfarbelowthepeakof81%in2007andtheaverageoverthelast20yearsof73%.IncreasingdemandforelectricityhasneverthelessledtoChinacompletingalmost40GWofnewcoalcapacityonaverageperyearoverthepastfiveyears,morethantherestoftheworldcombinedinthesameperiod.In2022,closeto90GWofnewcoal-firedcapacitywasapprovedtostartconstructionplusanother50GWplanned,addingtothenearly100GWunderconstructionasoftheendoftheyear,indicatingthattotalcoalcapacityinChinawillcontinuetoincreaseto2030.However,outputfromcoal-firedpowerplantsinChinapeaksaround2025anddeclinesbefore2030inboththeSTEPSandAPS.ThishappensbecausetheaveragecapacityfactorofcoalplantsinChinadeclinestojustover40%in2030intheSTEPSand35%intheAPS,comparedwith53%in2022,onthebasisthatChinawillgraduallyuseitscoal-firedpowermoretoprovideflexibilityandlesstodeliverbulkenergy,thoughthereisinevitablysomeuncertaintyaboutthespeedanddegreeofthisshift.After52030,thepathwaysforunabatedcoal-firedgenerationrapidlydiverge,withcoalusefallingfurtherandfasterintheAPSthanintheSTEPS.Figure5.21⊳ElectricitygenerationbysourceinChinaintheSTEPSandAPS,2010-2030TWh6000STEPS:4000Coal2000NaturalgasSolarPVWindHydroOtherlow-emissionsAPS201020202030IEA.CCBY4.0.Coal-firedelectricitygenerationissettodecreasefromthemid-2020intheAPSwhilesolarPVcapacitygrowsrapidlyandpasses2500GWby2030IEA.CCBY4.0.Theextenttowhichcoal-firedpowerandrelatedemissionsdeclineinthelongrunvariesbyscenarioasitishighlydependentontheabilityofrenewablesgrowthtooutpaceoveralldemandgrowth.CentraltorenewablesgrowthistheabilitytocontinuescalingupsolarPVandwinddeploymentinChina.Manufacturingcapacity,particularlyforsolarPV,createsahugeopportunitytodoso(seeChapter1).IntheAPS,solarPVinstalledcapacitynears5400GWby2030.Itcouldgoevenfaster,thoughsuccessfullyintegratingmoresolarPVrequiresovercominganumberofchallenges:theelectricitysystemhastobeequippedtointegratesolarPVandwindoutputinfull,andthatrequiresexpansionofelectricityChapter5Regionalinsights239transmission,modernisationofdistributiongrids,storagetechnologiesandanumberofoperationalchanges.Coaluseintheindustrysectorhasbeenincreasingrapidlysincetheturnofthemillennium.Itaccountedfor45%ofindustrialtotalconsumptionofenergyin2022andwasresponsiblefor30%oftotalcoalconsumptioninChina.Theironandsteelsub-sectoristhelargestindustrialcoalusertoday,consumingmorethan500Mtceofthetotal970MtceusedbyindustryinChina.Almost90%ofitssteelisproducedinintegratedblastfurnacebasicoxygenfurnace(BF-BOF)steelplantswherecokingcoalisusedbothasreagenttotransformironoreintoironandasafueltoheatirontoitsmeltingpoint(morethan1500°C).Ironandsteelcoalusepeakedin2014anddeclinesfrom2022inboththeSTEPSandAPSasscrapbecomesmorewidelyavailableforsecondaryproduction,whichismuchlessenergy-intensiveanduseselectricarcfurnacestoprovideheatratherthancoal(Figure5.22).Coaluseisalsowidespreadinotherheavyindustries,fromcementtochemicals,aswellasinlightindustries.StrategiestoswitchawayfromcoalinindustrysectorsareexploredinChapter3ofCoalinNetZeroTransitions(IEA,2022b).BecausecoalcombustioninChinaaccountsforaroundone-quarteroftotalenergy-relatedCO2emissions,cutsinitscoalusehaveamajorimpactontheglobaloutlookforemissions.IntheAPS,CO2emissionsfromcoalcombustioninChinadeclinefrom8.6Gtin2022to1.1Gtin2050.Thiscovers30%oftheglobalCO2emissionsreductionsthatareneededinthisscenariotomeettheemissionsreductiontargetsannouncedbycountriesallaroundtheworld.Whilethiswouldbeasignificantachievement,muchmoreneedstobedoneinChinaandothercountriestoenableafastertransitionawayfromunabatedfossilfuelsuseiftheworldistoachieveglobalnetzeroemissionsby2050.Figure5.22⊳SteelproductionbyprocessandfuelsharesinindustryinChinabyscenario,2022-20501.2Steelproductionandprocessshare100%FuelsharesinindustryIEA.CCBY4.0.0.975%Gt0.650%0.325%2022STEPSAPSSTEPSAPS2022STEPSAPSSTEPSAPS2030205020302050Scrap-basedEAFH₂DRI-EAFBOFProduction(leftaxis)ElectricityOtherCoalIEA.CCBY4.0.Coaluseinindustryplummetsaselectrificationprogressesinmostsub-sectors.Steelincreasesrelianceonsecondaryproductionandhydrogen-basedironproduction.Note:Scrap-basedEAF=steelproductionfromscrapinelectricarcfurnace;H2DRI-EAF=steelproductioninelectricarcfurnaceusingironfromhydrogen-baseddirectreducediron;BOF=steelproductioninbasicoxygenfurnaceusingironfromablastfurnaceorfromasmeltingreductionfurnace.240InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20235.9India5.9.1KeyenergyandemissionstrendsFigure5.23⊳KeytrendsinIndia,2010-2050Oildemand(mb/d)Naturalgasdemand(bcm)Coaldemand(Mtce)1020010005100500Transport20502010Industry20105Industry201020502050Electricitygeneration(TWh)Investment(billionUSD)CO2emissions(GtCO2)47000300350015022010SolarPVCleanenergyPower20502050201020502010STEPSAPSIEA.CCBY4.0.IEA.CCBY4.0.Throughmuchofitsmodernhistory,Indiahasworkedtobuildpowergenerationandrefiningcapacity,provideaffordableaccesstoenergyandensuresecurityofsupply.Alothasbeenachievedinthepastfewdecades.Since2000,Indiahasbroughtelectricityto810millionpeople,largerthanthepopulationoftheEuropeanUnionandtheUnitedStatescombined.Indiahasalsobroughtcleancookingaccessto655millionpeopleoverthesameperiod,although430millionpeoplecontinuetoliveinhouseholdsthatusetraditionalbiomasstoday.Overthepastfiveyears,solarPVhasaccountedfornearly60%ofnewgenerationcapacity.Indiahashadthesinglelargestlight-emittingdiode(LED)adoptioncampaignintheworld,witharound370millionLEDsdistributedthroughtheUJALAschemeby2023.Indiahasalsoachievedself-sufficiencyinpetroleumrefiningcapacitydespitebeinganetcrudeoilimporter,althoughcertainpetroleumproductscontinuetobeimported.Indiaismovingintoadynamicnewphaseinitsenergydevelopmentmarkedbyalong-termnetzeroemissionsambition,increasedregulatorysophistication,afocusoncleanenergydeployment,andthecreationofdomesticcleanenergytechnologysupplychains.Chapter5Regionalinsights241RecognisingthepotentialtotransformitsenergysectorandreducetheimportburdenoffossilfuelswhilereducingCO2emissions,Indiahasannouncedanetzeroemissionstargetby2070,andhasputinplacepoliciestoscaleupcleanenergysupplyandcleantechnologymanufacturing.WhilecleanenergyinvestmentinIndiamorethandoublesintheSTEPSby2030fromaroundUSD60billionin2022,investmentneedstonearlytriplebytheendofthisdecadetobeonatrajectorytomeetitsnetzeroemissionstarget,whichisreflectedintheAPS(Figure5.23).IntheSTEPS,Indiaseesthelargestenergydemandgrowthofanycountryorregionintheworldoverthenextthreedecades.AlthoughIndia’spopulationgrowthhasslowedtoreachreplacementlevels,itsurbanpopulationincreasesby74%andpercapitaincometriplesby2050.Industrialoutputexpandsrapidly,forexamplethroughatriplingofoutputofironandsteel,anddoublingofcement,plusthereisaninefoldincreaseinresidentialairconditionerownershipby2050.Asaresult,demandforoilandnaturalgasincreasesintheSTEPSbynearly70%between2022and2050,whilecoaldemandincreasesby10%,evenassolarPVmakesinroadsintoelectricitygeneration.Asaresult,India’sannualCO2emissionsstillrisenearly30%by2050,whichisoneofthelargestincreasesintheworld.IntheAPS,theincreaseincleanenergyinvestmentchangestheoutlook.IntheSTEPS,solarprovidesnearly45%oftotalgeneratedpowerby2050;intheAPS,itcrosses50%.InboththeSTEPSandAPS,Indiaachievesitstargetof50%non-fossilpowergenerationcapacityby2030.CleanenergyinvestmentintheAPSoverandabovethoseintheSTEPSalsodrivesfastergrowthinelectromobility,low-emissionshydrogen,gridexpansionsandothercleanenergyinfrastructure.Asaresult,India’sannualCO2emissionsfallsharplyintheAPSbyover40%fromcurrentlevelsby2050,eventhoughitsGDPquadruplesoverthisperiod.Table5.10⊳KeypolicyinitiativesinIndiaPolicyDescriptionNetZeroEmissionsby•Indiaannouncedtheambitiontoreachnetzeroemissionsby2070in2021.It2070wasformallyadoptedasapartofitsupdatedNationallyDeterminedContributionin2022.Renewableenergyand•Aimstohave50%ofpowergenerationcapacityfuelledbynon-fossilsourcestransmissiontargetsby2030,comparedto41%in2022.Ithasalsosetatargetof500GWofnon-fossilcapacityby2030.•TheGreenEnergyCorridorprojectaimstocreatetransmissioncapacitytointegratearisingshareofvariablerenewablepower.Itstransmissionplantargetstheintegrationof500GWofrenewablecapacityby2030.ProductionLinked•ProvidesubsidiestowardsthecreationofnewmanufacturingcapacityofsolarIncentivesPVmodulesandmodernbatteries.NationalGreen•Targetslow-emissionshydrogenproductioncapacityof5Mtperyear(withanHydrogenMissionassociatedrenewableenergycapacityadditionof125GW).Thisistobeaccompaniedbypoliciestogeneratedemandforlow-emissionshydrogen,particularlyfromindustry.IEA.CCBY4.0.CarbonMarket•Passedalawin2022thatsetsthestageforthecreationoftheIndianCarbonMarket,acarboncredittradingscheme.242InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20235.9.2ImpactofairconditionersonelectricitydemandinIndiaOverthepastfivedecades,Indiahaswitnessedover700heatwaveevents,whichhaveclaimedover17000lives(Rayetal.,2021).Fuelledbyitsgeographicandmeteorologicalconditions,airconditionerownershipinIndiahasbeensteadilyrisingwithgrowingincomes,triplingsince2010toreach24unitsper100households.Theimpactofcoolingneedsonelectricityconsumptionisalreadyclear.Electricitydemandissensitivetotemperatures,andinIndia’scasethereisasharpincreaseindemandastemperaturescrossthe25°Cthreshold(Figure5.24).Electricityconsumptionduetospacecoolingincreased21%between2019and2022,andtodaynearly10%ofelectricitydemandcomesfromspacecoolingrequirements.Figure5.24⊳DailyaverageelectricityloadversusdailytemperatureinIndia,2019and2022Dailyaverageelectricityload(GW)2005Dailydemand20221752019Thermosensitivity150202220191251001520253035Dailyaveragetemperature(°C)IEA.CCBY4.0.Electricitydemandrisessharplywithtemperaturesabove25°C;useofmorespacecoolingappliancesispushingelectricitydemandupHouseholdairconditionerownershipisestimatedtoexpandninefoldby2050acrosstheIEAscenarios,outpacingthegrowthinownershipofeveryothermajorhouseholdapplianceincludingtelevisions,refrigeratorsandwashingmachines(Figure5.25).ResidentialelectricitydemandfromcoolingincreasesninefoldintheSTEPSby2050.By2050,India’stotalelectricitydemandfromresidentialairconditionersintheSTEPSexceedstotalelectricityconsumptioninthewholeofAfricatoday.IntheAPS,however,electricitydemandforairconditionersisnearly15%lowerin2050asitisintheSTEPSasaresultofincreaseduseofenergy-efficientairconditionersandthermalinsulationinbuildings.Thisreductionitselfislargerthanthetotalelectricitygenerationbyseveralcountriestoday,suchasthatoftheNetherlands.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter5Regionalinsights243Figure5.25⊳HouseholdapplianceownershipinIndiato2050andcontributionofcoolingtopeakelectricalloadbyscenario,2030HouseholdapplianceownershipElectricitypeakloadbyend-use2.4200UnitsperhouseholdIndex(2022=100)1.81501.21000.6502000202220502022203020222030STEPSOtherAPSTelevisionRefrigeratorAirconditionerDishwasherWashingmachineCoolingIEA.CCBY4.0.Airconditionersareprojectedtobethefastestgrowinghouseholdappliance,whichdriveshalfofthegrowthinpeakelectricitydemandto2030intheSTEPSIEA.CCBY4.0.ThegrowthinownershipanduseofairconditionersandothercoolingequipmentisalsooneofthekeydriversoftheincreaseinpeakelectricitydemandinIndia.IntheSTEPS,peakelectricitydemandrisesaround60%fromthe2022levelby2030andcoolingaccountsfornearlyhalfofthisincrease.IntheAPS,however,theimplementationofbuildingcodes,theuseofmoreefficientappliancesandtheadoptionofdemandresponsemeasuresenablethesamecoolingneedstobemetwithlessenergy.Thisreducespeakelectricitydemandgrowthbynearlyone-quartercomparedtotheSTEPS.Giventhattheelectricitysystemissizedtomeetpeakdemand,lowerpeakdemandhelpstolowerelectricityinvestmentneedsandsystemcosts.AlthoughsolarPVmatcheswellwithdaytimecoolingneeds,coolingdemandisalsosignificantinIndiaduringthelateeveningandatnight.Loweringcoolingdemandthroughenergyefficiencypoliciesthereforereducestheneedforinvestmentinbatteriesorexpensivestandbygenerationcapacity,andthushelpstointegraterenewablesmorecosteffectively.5.9.3WilldomesticsolarPVmodulemanufacturingkeeppacewithsolarcapacitygrowthinIndia?Indiahashistoricallybeenanetimporteroffossilfuels,andithasnowbecomeanimporterofmoderncleanenergytechnologiesasitscalesupsolarandwindpowergenerationcapacity.Forexample,itsimportsofsolarPVmodulesin2021-2022werevaluedatUSD3.4billion(MCI,2023).Recognisingthisimportdependenceandmindfulofthehighlevelsofconcentrationincleanenergytechnologysupplychains,thenationalgovernment244InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023launchedtheProductionLinkedIncentives(PLI)programmein2020tosupportdomesticmanufacturinginarangeofcriticalsectors,includingsolarPVmodulesandadvancedchemistrycellbatterymanufacturing.ThePLIprogrammeforsolarPVmodulemanufacturingbudgetednearlyUSD2.5billioninsubsidieswiththeaimofcreating65GWperyearofnewmanufacturingcapacity.Manufacturingcompanieswereselectedintwotranchesin2023andatotalof48GWofnewcapacitywasdeemedeligibleforsubsidyawardsoncemanufacturingbegins.Thesenewproductionlinesareexpectedtocomeonlinewithintwotothreeyears.Figure5.26⊳SolarPVmodulemanufacturingcapacityandsolarPVcapacityadditionsinIndiabyscenarioto2030SolarmodulemanufacturingcapacitySolarcapacityadditionsSTEPS580GW/yearAPS6040202022PLI-1PLI-2202720222023202720232027-26-30-26-30IEA.CCBY4.0.IfplannedsolarPVmodulemanufacturingcapacityadditionsundertheProductionLinkedIncentivesmaterialise,theywouldbeadequatetomeetdomesticdemandthisdecadeNote:PLI-1andPLI-2refertothetwotranchesoftheProductionLinkedIncentivesprogrammeunderwhichsolarmanufacturerswereselectedtoreceivesubsidiesinlieuofcreatingnewmanufacturingcapacity.IEA.CCBY4.0.Indiaisexpectedtomeetits2030targettohavehalfofitselectricitycapacitybenon-fossilwellbeforetheendofthedecade.IfthenewsolarPVmodulemanufacturingcapacityunderthePLIprogrammecomesfullyonlineby2026,itwouldprogressthesolarPVmodulemanufacturingcapacityinIndiatowelloverwhatisneededuntiltheendofthisdecadenotjustintheSTEPSbutalsointheAPS(Figure5.26).SolarPVmoduleimportscouldcontinueforafewyearsbecausedeveloperswillsourcethecheapestpanelsavailable,becausethecapacityutilisationfactorremainslowerthanthenameplatecapacity,andbecausetherearelagsbetweenthenameplatecapacitycomingonlineandthepanelsbeingmanufactured,shippedandinstalled.Nonetheless,asdomesticproductionrampsup,solarPVmoduleimportswilldeclineanditwillhelptoestablishIndiaasareliableexporter.Chapter5Regionalinsights2455.10JapanandKorea5.10.1KeyenergyandemissionstrendsFigure5.27⊳KeytrendsinJapanandKorea,2010-2050Oildemand(mb/d)Naturalgasdemand(bcm)Coaldemand(Mtce)82003004100150Transport2050Power2050Industry2050201020102010Electricitygeneration(TWh)Investment(billionUSD)CO2emissions(GtCO2)23000200150010012010SolarPVCleanenergyPower20502050201020502010STEPSAPSIEA.CCBY4.0.IEA.CCBY4.0.JapanandKoreacontinuetomapoutsecurepathwaystoreachnetzeroemissionspledgesby2050,butitremainschallengingtodecarboniselargeindustrialeconomiesthathavehistoricallyreliedheavilyonimportedfossilfuels.IntheSTEPS,theshareofcoalandnaturalgasinthepowermixofthetwocountries–currentlyat65%–fallssharplyoverthenextfewdecadesasJapan’sGreenTransformationpolicyandKorea’sBasicPlanforLong-termElectricitySupplyandDemanddramaticallyincreasetheshareoflow-emissionsfuelsingeneration,includingsolarPV,windandnuclear.Theshareofgenerationfromlow-emissionstechnologiesofbothcountriescombinedrisesfrom30%todaytoaround85%by2050intheSTEPS.Naturalgasdemandalmosthalvesbymid-century,withremainingwidespreaduseinthepower,buildingandindustrialsectors,whilecoalusedeclinesbytwo-thirds,largelyinindustry(Figure5.27).Reducedoildemandisshapedbyincreasedadoptionofzeroemissionsvehicles(ZEV),salesofwhichrisesharplyasgovernmentsupportschemesinbothcountriesincentivisetheiruptake:ZEVsaccountfor246InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook202365%ofnewvehiclessoldby2050,bringingoildemanddownfromnearly6mb/dtodaytolessthan4mb/dby2050.TheAPSincorporatesthepledgesstatedbyJapanandKoreatoreachclimateneutralityby2050.Japan’sGreenGrowthStrategyandKorea’sCarbonNeutralityandGreenGrowthActenvisagefulldecarbonisationofthepowersector.Japanalsoaimsforallnewcarsandvanssoldtobeeitherbatteryelectric,plug-inhybrid,hybridorfuelcellvehicles,withatargetdateof2035forcarsand2040forvans.Koreahassetatargetformorethan80%ofcarsalestobelow-emissionsvehiclesby2030.Bothcountrieshavealsointroducedguidelinesfornewbuildingstomeetzero-carbonstandardsbytheendofthisdecade.Asaresult,investmentincleanenergytechnologiesintheAPSrapidlyscalesuptooverUSD175billionby2050.Table5.11⊳KeypolicyinitiativesinJapanandKoreaPolicyDescription5Japan:BasicHydrogen•AimstoacceleratepublicandprivateinvestmentinthehydrogensupplychainStrategywithJPY15trillion(USD114billion)overthenext15years.(updatedin2023)•Planstoinstallaround15GWofelectrolysersbyJapanesecompaniesbothdomesticallyandabroadby2030.Japan:Green•Aimstoachievedecarbonisation,energysecurityandeconomicgrowthwithTransformation(GX)publicandprivateinvestmentofJPY150trillion(USD1trillion)overthenextbasicpolicytenyears.•Intendstofundthepromotionofrenewableenergy,i.e.R&Doffshorewindcostreduction,andtransition,i.e.buildingmasshydrogensupplychain,andextendthelifetimeofexistingnuclearreactors.Korea:10thBasicPlan•Seekstoincreasetheshareofrenewablesandnuclear–ashiftfrompreviousforLong-termphase-outplans–inthepowermixto31%and35%respectivelyandreduceElectricitySupplyandtheshareofcoalto15%by2036.Demand•Planstoexpandthepowergenerationcapacityfrom148GWlevelin2023to239GWby2036.Korea:1stNational•Includes2023NDCupdatesofthe2021NDCwhichmaintainsthesameGHGBasicPlanforCarbonreductiontargetat40%from2018levelsbutwithadjustedsectoraltargets.NeutralityandGreenGrowth•Intendstostrengthenthepowersectorreductiontargetto45.9%by2030from2018levels,withincreasedrolesfornuclearandrenewables,andtoreducethetargetfortheindustrysectortoa11.4%cutby2030from14.5%inthepreviousNDC.Note:JPY=Japaneseyen;NDC=NationallyDeterminedContribution.JapanandKoreabothhavesmalllandareasrelativetothesizeoftheirpopulationsandindustrialsectors:thisisadisadvantagewhenitcomestodeployingrenewablessuchassolarPVandonshorewind.Theirdistinctgeographicalsettingsrequirethetwocountriestoexploreadiversifiedmixofcleantechnologieswhichincludesmajorrolesforimportedlow-emissionshydrogenandhydrogen-richfuels,floatingoffshorewindandnuclear.IEA.CCBY4.0.Chapter5Regionalinsights2475.10.2ChallengesandopportunitiesofnuclearandoffshorewindBothKoreaandJapanneedtodeterminetheirspecificpathandmixoftechnologiestoachievesecurecleanenergytransitions.Inthepowersector,bothcountrieshavebeeninvestinginsolarPV,whichexpandedsignificantlybetween2010and2022.Today,however,fossilfuelsstillaccountfortwo-thirdsofpowergenerationinbothcountries,mainlyfromcoalandnaturalgas.Furtheraccelerationofeffortsoncleanelectricitygenerationisnecessarytoachievetheirgoalsforcleanenergytransitions.Nuclearpowerandoffshorewindhavethepotentialtomakeasignificantcontributiontodecarbonisingthepowersector,andinourscenariostheirroleinelectricitygenerationrisesrapidly(Figure5.28).TheshareofnuclearpowerinelectricitygenerationinJapanandKoreaincreasesby75%inbothSTEPSandAPSby2050.Maintainingeffectiveandefficientsafetyregulationsisclearlyessentialinthiscontext.Figure5.28⊳Growthinnuclearandoffshorewindelectricityrelativetototalelectricitygenerationgrowthbyscenario,2022-2050JapanKorea400TWhOffshorewind300Nuclear200Totalelectricitygeneration1000-100STEPSAPSSTEPSAPSSTEPSAPSSTEPSAPS2030-502022-302030-502022-30IEA.CCBY4.0.Nuclearplaysamajorroleinincreasedelectricitygenerationby2030whileoffshorewindisexpectedtodeveloprapidlyafter2030IEA.CCBY4.0.Offshorewindcouldunlocktheenormousenergypotentialoflargeoceanareassurroundingbothcountriesandbecomeamajorsourceofrenewableenergy.OffshorewindcapacityinJapanandKoreatotalsonly0.3GWtoday,duelargelytoalackoftransmissioncapacityandthehighcostoffacilities.TheuniquegeographicalcharacteristicsofKoreaandJapanaddtothechallenges:theseasurroundingbothcountriesismorethan50metresdeepinmanyplacesandhassteepslopeswhichmakeitimpossibletodeploytraditionalseabed-mountedoffshorewindinstallations.Technologicaldevelopmentandcostreductionsinfloatingsystemscouldaccelerateexpansionofoffshorewind,whichisintheearlydeploymentstagetoday.Governmentsupportisplanned,asacceleratingthefull-scaleroll-outoffloating248InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023systemsrequiresextensivefundingforR&Dandforeffortstode-riskinvestmentinearlyprojects.PoliciesforoffshorewindinJapanandKoreaaimtotacklethechallengesbysimplifyingprojectapprovalprocesses,buildingresilientsupplychainsanddevelopingefficientlowcoststructuresthatcanadapttotheparticulargeographicalandclimaticenvironment.IntheSTEPS,combinedforJapanandKoreaoffshorewindincreasesitscontributiontogenerationfromlessthan0.1%todayto15%by2050.IntheAPS,itscontributioninelectricitygenerationincreasesto20%,whichreachestheshareofsolarPV,andoffshorewindandnucleartogetheraccountfornearly45%oftotalgenerationby2050intheAPS.5.10.3Whatrolecanhydrogenplayintheenergymixandhowcanthegovernmentsdeployit?IntheAPS,JapanandKoreaimportsignificantquantitiesofhydrogenandhydrogen-based5fuelsforuseinthepowersectorandfordirectuseinindustry.By2050,KoreaandJapanaccountforalmost40%ofglobalhydrogenimports(Figure5.29).Figure5.29⊳Importedhydrogenandhydrogen-basedfuelsintheAPS,2030and2050203020502.0IEA.CCBY4.0.1.5EJ1.00.5JapanKoreaEuropeanRestJapanKoreaEuropeanRestUnionofworldUnionofworldSyntheticoilproductsHydrogenAmmoniaIEA.CCBY4.0.JapanandKoreabecomethesecond-largestimportersofhydrogenandhydrogen-basedfuelsaftertheEuropeanUnionTodayJapanandKorea’sshareofhydrogenintotalfinalconsumptioniscloseto0%.Itismainlyproducedthroughnaturalgasreformingandconsumedinoilrefineries.Bothgovernmentsaimtoexpanditsuseincomingdecadeswith20%ammoniaco-firingby2030(50%by2035inJapan)toreducethecarbonintensityoftheexistingcoal-firedfleet.Afterthepowersector,demandforhydrogenwillbedrivenbyhard-to-abatesectorssuchaslong-distancetrucking,aviation,shippingandheavyindustry(Figure5.30).InaviationandChapter5Regionalinsights249shipping,demandislikelytobefocussedonsynthetickeroseneandammonia.By2050,hydrogenaccountsfor2%oftotalfinalconsumptionintheSTEPSandupto9%intheAPS.Figure5.30⊳HydrogensupplybysourceanddemandbysectorinJapanandKoreabyscenarioSTEPSAPSIEA.CCBY4.0.2500PJ20001500100050020222030205020302050DemandTransportIndustryBuildingsSupplyPowerRefineryOtherUnabatedfossilfuelsFossilfuelswithCCUSBy-productElectrolysisImportedhydrogenIEA.CCBY4.0.Fossilfuel-basedhydrogenisusedonaninterimbasisuntillow-emissionshydrogensupplyscalesupmostlyforco-firingandinhard-to-abatesectorsNotes:Transformationincludesco-firinginpowergeneration,hydrogenasaninputtohydrogen-basedfuelsanduseinbiofuelproduction.Importedhydrogenincludeshydrogenfromcrackingofimportedammonia,importsofliquefiedhydrogenandsyntheticoilproducts.By-productreferstohydrogenproducedinnaphthareformersinrefineriesandpetrochemicalfacilities.Whileunabatedfossilfuel-basedhydrogenmeetsmostexistingdemandtoday,JapanandKoreaarelookingforlow-emissionshydrogensupplytomeetnewdemandandreplaceexistingunabatedproductioncapacities.IntheAPS,hydrogenproducedfromelectrolysisrampsupsignificantly,accountingfornearlythree-quartersofdomesticproductioninthetwocountriesin2050.Tohelpdevelopandsecurethelow-emissionshydrogenthattheyneed,JapanandKoreaareactivelyseekingpartnershipswithpotentialexportingcountriesandtechnologyproviders.Long-terminvestmentandcontractsarerequiredacrosshydrogenvaluechains,fromupstream(fertilisersandprovidersofrenewableelectricity,electrolysersandCO2capture)totransportationandstorage(includingships,portsandplantstoconvertdifferenthydrogencommodities).Progressisbeingmadeincreatingreliabledemand,butmoreneedstobedoneonthatfronttosupportlong-distancetransportandindustrialuseswhereoff-takerisksarehinderingtheadoptionofnewequipmentandprocesses.Thedevelopmentofinternationalstandards,certificationarrangementsandemissionsaccountingframeworksallcouldhelpthescalingupthatisneededandtoassistgovernmentstoachieveemissionsreductiontargetthroughtheuseofimportedhydrogen.250InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook20235.11SoutheastAsia5.11.1KeyenergyandemissionstrendsFigure5.31⊳KeytrendsinSoutheastAsia,2010-2050Oildemand(mb/d)Naturalgasdemand(bcm)Coaldemand(Mtce)83005004150250Transport2050Industry2050Power52010201020102050Electricitygeneration(TWh)Investment(billionUSD)CO2emissions(GtCO2)3.0500025025001251.52010SolarPV2010CleanenergyPower2050205020502010APSIEA.CCBY4.0.STEPSIEA.CCBY4.0.SoutheastAsiaishometonearly9%oftheworldpopulationandaccountsfor6%ofglobalGDP.Itisamajorengineofeconomicgrowthandhasanoutsizedinfluenceinglobalenergy.ThecollectiveGDPofcountriesinSoutheastAsiahasnearlytripledsince2000,outpacinggrowthinglobalGDPoverthisperiod.Asaresult,energydemandgrowthintheregionhasalsooutpacedtheglobalaverage,andthatissettocontinue:intheSTEPS,theregionexperiencesthesecond-highestenergydemandgrowthintheworldafterIndiauntil2050,drivenbyanincreasingpopulation,risingstandardsoflivingandrapidurbanisation.Asaresultofitscontinuedrelianceonfossilfuels,SoutheastAsiaalsoseesthelargestabsolutegrowthofCO2emissionsofanyregionintheworld.Itsemissionsincreaseby46%from2022levelsby2050intheSTEPS,withcoalresponsibleformuchoftherise.SoutheastAsiaisoneofthefewregionsintheworldwhereelectricitygenerationfromcoalincreasesintheSTEPSthroughto2050.Whiletheshareofcoalinpowergenerationfallstolessthanone-thirdby2050intheSTEPS,itisstillthesecond-highestofanyregionintheworldby2050.Chapter5Regionalinsights251TodaySoutheastAsiareliesheavilyoncoalforelectricitygeneration.TwoambitiousJustEnergyTransitionsPartnerships(JETP)wereestablishedinSoutheastAsiain2022,onewithIndonesiaandanotherwithVietNam.Thepartnershipspromisebetteraccesstointernationalfinancingtoacceleratetransitionsawayfromunabatedcoal-firedpowertohelpreduceemissions.InVietNam,thelatestpowerdevelopmentplanseekstoreshapeitsenergysystem,includingbymovingawayfromunabatedcoaluseandbyscalinguptheuseoflow-emissionshydrogenandammoniainthepowersector.Table5.12⊳KeypolicyinitiativesinSoutheastAsiaPolicyDescriptionNetzeroemissionsambitions•Commitmentstonetzeroemissionsby2050(Laos,Malaysia,Singapore,VietNam,BruneiDarussalam),by2060(Indonesia)andby2065(Thailand).JustEnergyTransitionPartnership•Indonesia,Malaysia,Philippines,VietNam,SingaporeandCambodiahaveRegionalinitiativescommittedtotheGlobalMethanePledge.SupporttoEVs•JustEnergyTransitionPartnershipswithIndonesia(USD20billion)andVietNam(USD15.5billion).•ASEANPlanforActiononEnergyCo-operationsetsoutaspirationaltargetsincludingareductionofenergyintensityby32%in2025basedon2005levels,andanincreaseofrenewablesto23%by2025intheregion.•ASEANPowerGridcollaborationwhichwillbecarriedoutbytheASEANCenterforEnergyandtheUSAgencyforInternationalDevelopment.•AsiaZeroEmissionsCommunityinitiativebyJapantobringtogethereconomiestowardstransitionstonetzeroemissions–USD8billionby2030towardscleanenergyprojectsinparticipatingSoutheastAsiancountriesincludingIndonesia,Philippines,ThailandandVietNam.•MultiplepoliciestosupportEVuse,suchasreducedvalue-addedtaxandsubsidies(Indonesia);taxincentivesforcompaniesrentingEVsandsubsidiesforEVchargermanufacturing(Malaysia);andcellmanufacturing(Thailand).Note:ASEAN=AssociationofSoutheastAsianNations.SoutheastAsiahasemergedasaglobalhubforcleanenergytechnologymanufacturing,withVietNamandIndonesiajoiningtheranksofexportersofequipmentsuchassolarPVmodules.However,theracetobuildindustrialcapacityrisksleadingtorapiddevelopmentofcaptivecoalprojects,suchasfornickelprocessinginIndonesia.Overall,cleanenergyinvestmentintheregionwasnearlyUSD30billionin2022,whichlookstomorethandoublebytheendofthisdecade.Nevertheless,thereismoretodotobeontracktodeliverlongertermambitionsasreflectedintheAPS.Forthistohappen,cleanenergyinvestmentneedstonearlyquadrupleby2030andcontinuerisingafterwards.InvestmentonthisscaleintheAPSleadstosolarpowerincreasingalmostsixfoldby2030andtocoal-firedpowergenerationhalvingby2050from2022levels,reducingoverallCO2emissionsbyover40%,evenastheregion’seconomygrowsbywellovertwo-and-half-timeslarger.IEA.CCBY4.0.252InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.5.11.2HowcaninternationalfinanceacceleratecleanenergytransitionsinSoutheastAsia?Marshallingthenecessaryfinancetofulfilcleanenergytransitionobjectivescanbechallengingforemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesastheytendtorelyheavilyonpublicinvestmentbygovernmentsorstate-ownedenterprises.Theyfacerelativelyhighborrowingcosts,andsteppingupinvestmentcallsformultiplesourcesoffinance:bothdomesticandinternationalprivatefinancehavepivotalrolestoplay.Mobilisingthiscapitalrequiresinternationalco-operation,involvementofinternationalanddevelopmentfinanceinstitutions,andreformstodomesticpolicyandregulatoryframeworksthatfacilitateprivateinvestment.JustEnergyTransitionPartnerships,launchedatCOP26inGlasgowin2021,attempttoeadcodnreosmsiethsisancdhaallceonagl-ed.eTpheenydeanreteamfeinragnincginmgacrok-eotpaenrdatdioenvemloepcinhganeicsomnobmetywweheinchacdovmanmceitds5toambitiousemissionsreductiontargetsanddefinesacrediblenationaltransitionpathway.TheJETPframeworkincludesmultilateraldevelopmentbanks,nationaldevelopmentbanksandprivatelenders.Theaimistomakeavailableamixoffinancing,someatconcessionalterms,withthegoalofmobilisingmoreresourcesbycatalysinginternationalprivateinvestment.TheJETPbetweenIndonesiaandtheInternationalPartnersGroup(IPG)–whichincludesCanada,Denmark,EuropeanUnion,France,Germany,Italy,Japan,Norway,UnitedKingdomandUnitedStates–wasdevelopedtohelpIndonesiagetontracktobringemissionstonetzeroby2060.TheJETPhelpedstrengthenIndonesia’sambitions,bringingitspledgesinlinewiththemilestonessetoutintheEnergySectorRoadmaptoNetZeroEmissionsinIndonesia(IEA,2022c),whichwaspreparedinco-operationwiththeIndonesianMinistryofEnergyandMineralResources.Puttingtheeconomyonatrajectoryconsistentwithreachingnetzeroemissionsby2060necessitatesmorethandoublingtotalannualinvestmentintheenergysectorby2030,raisingtheshareofrenewablesinthepowersectortoone-thirdby2030(Figure5.32).Italsomeanspowersectoremissionspeakingatnomorethan290Mtin2030,andunabatedcoal-firedelectricitygenerationpeakingataroundthesametime.Inpursuitoftheseobjectives,theIndonesiaJETPaimstosecureaninitialUSD20billioninfinancingoverthreetofiveyearsfrombothpublicandprivatesources.USD10billionconsistsofpublicsectorfinancebackedbytheInternationalPartnersGroup,withtheremaindertobeobtainedthroughacombinationofmarket-rateloansandprivateinvestment.AnotherobjectiveofthepartnershipistohelpIndonesiaupdateitstechnicalandregulatoryframeworksinordertoovercomebarrierstoinvestment,facilitatethedeploymentofsupportandmobilisefurtherdomesticandinternationalcapitaltospeedupthetransitiontonetzeroemissions.TheJETPbetweenVietNamandtheIPGwasdevelopedtosupportthecountryinpursuitofitstargettoreachnetzeroemissionsby2050.Itreflectsitsambitiontoaccelerateitstransitiontoacarbonneutralenergysystem,includingitsintentiontobringaboutapeakinChapter5Regionalinsights253emissionsby2030,toceaseissuingpermitsfortheconstructionofnewcoal-firedpowerplants,topromotethedevelopmentofrenewablesandtoimproveenergyefficiency,whileensuringenergyremainssecureandaffordable.TheVietNamJETPaimstomobiliseatleastUSD15.5billionoverthenextfiveyears.Halfofthis,nearlyUSD8billion,willbepublicsectorfinancebackedbytheIPG.AswithIndonesia,theaimisforinternationalfundingtohelpcatalyseadditionalprivatesectorfinancethatatleastmatchesthelevelofpublicsectorfinance,andtohelpVietNamattractthecapitalitneedsasitscleanenergytransitionmovesforward.Figure5.32⊳EnergysectorinvestmentandkeymilestonesinthecleanenergytransitioninIndonesiaintheAPSTotalenergyinvestmentPowersectoremissionsCoalunabatedelectricity(BillionUSD2022,MER)(MtCO₂)(TWh)60300300Cleanenergy4020020020100100201820202022203020222030204020502022203020402050IEA.CCBY4.0.Togetontrackfornetzeroemissionsby2060andmeettheJETPtargettopeakemissionsinthepowersectorby2030,totalannualenergyinvestmentneedstodoubleby2030VietNam’sPowerDevelopmentPlan(PDP)8,approvedinMay2022,setsoutitsincreasedambitionanddetailsapathwayforpowersectordevelopmentto2030.Italsoincludesalongertermvisionto2050.InlinewithJETPcommitments,coal-firedcapacityisplannedtopeakatabout30GWin2030,downfrom55GWinthepreviousPDP.Beyond2030,coalplantswouldhavetoclosewhentheyare40yearsoldunlessconvertedtorunonammoniaorbiomass.Significantlyraisingtheshareofvariablerenewablesintheelectricitymixisanotherkeycomponentoftheplan,andisaccompaniedbyarecognitionthatsubstantialinvestmentingridsisneededtomakethiswork.Offshorewindisplannedtoplayanimportantrole,reflectingthefactthatVietNamishometosomeofthebestoffshorewindresourcesinSoutheastAsia.IEA.CCBY4.0.5.11.3Howcanregionalintegrationhelpintegratemorerenewables?CleanenergytransitionsinSoutheastAsia,supportedbytheJETPprogramme,willreshapepowersystemsandhelptostrengthenenergysecurity.Establishingmarketsand254InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023mechanismsforrenewablesdeployment,scalingupcleanenergyinvestmentandlimitingcoal-firedpowerwillbecrucialintheperiodto2030.IntegratingrisingwindandsolarPVcapacityintoelectricitysystemswillbecomeanincreasinglycentraltaskafter2030,astheirshareoftheoverallgenerationmixrisesfrom20%in2030toover50%in2050intheAPS,comparedwithjust5%in2022(Figure5.33).Figure5.33⊳WindandsolarPVintotalelectricitygenerationandgridinvestmentinSoutheastAsiabyscenarioShareofsolarPVandwindGridinvestmentsAPSinelectricitygeneration100%BillionUSD(2022,MER)4075%305APSSTEPS50%2025%STEPS10201020202030204020502018202020222030205020302050IEA.CCBY4.0.GridinvestmentrequirementsquadrupleintheAPSby2050astheshareofvariablerenewableenergyinelectricitysupplyincreasesIEA.CCBY4.0.EnhancedregionalintegrationthroughstrengthenedelectricitygridscanimproveelectricitysecurityandaidrenewablesintegrationinSoutheastAsiainseveralways.Flexibilityneedscanbereducedthroughregionalintegrationbyenablingelectricitydemandtobebalancedoverlargerareas,whichtendstosmoothoutvariabilityandcanmoderatepeakloads.FlexibilityneedscanalsobereducedbylinkingsystemsthatrelyonwindandsolarPVtovaryingdegreesandthathavedifferentproductionprofiles.Regionalintegrationcanalsoboosttheavailablesupplyofflexibilitybyfacilitatingthepoolingofawidersetofresources,includinghydropower,fossilfuel-basedcapacityandenergystorage.Betterintegratedsystemscouldalsomitigatetheriskofoutagesandincreasesystemresilience.Regionalintegrationrequiresthescalingupofinvestmentinelectricitygrids,includingininterconnectionsbetweencountries.InSoutheastAsia,gridinvestmentrisesfromaroundUSD10billionin2022toUSD16billionin2030andUSD40billionin2050intheAPS.ThereisalreadygrowingmomentumforincreasingregionalintegrationoftheelectricitynetworkinSoutheastAsia.ProgrammessuchastheASEANPowerGridhaveboostedcollaborationbetweencountriesandbroughtgreaterawarenessoftheadvantagesofintegrationfortheregion.Chapter5Regionalinsights255IEA.CCBY4.0.ANNEXESBoxA.1⊳WorldEnergyOutlooklinksWEOhomepageWEO-2023informationiea.li/weo23WEO-2023datasetsDatainAnnexAisavailabletodownloadfreeinelectronicformatat:iea.li/weo-dataAnextendeddataset,includingthedatabehindfigures,tablesandtheWEO-2023slidedeckisavailabletopurchaseat:iea.li/weo-extended-dataModellingDocumentationandmethodology/Investmentcostsiea.li/modelRecentanalysisNetZeroRoadmap:AGlobalPathwayiea.li/netzerotoKeepthe1.5°CGoalinReachElectricityGridsandSecureEnergyTransitionsiea.li/gridsGlobalEVOutlook2023iea.li/GEVO2023WorldEnergyInvestment2023iea.li/wei2023FinancingcleanenergyinAfricaiea.li/AfricaEnergyFinancingScalingupPrivateFinanceforCleanEnergyiniea.li/finance-emdeEmergingandDevelopingEconomiesGlobalMethaneTracker2023iea.li/methane-tracker23CriticalMineralsMarketReview2023iea.li/critical-minerals23TheFutureofHeatPumpsiea.li/heatpumpsDatabasesPolicyDatabasesiea.li/policies-databaseSustainableDevelopmentGoal7iea.li/SDGEnergysubsidies:iea.li/subsidiesTrackingtheimpactoffossil-fuelsubsidiesIEA.CCBY4.0.IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsGeneralnotetothetablesThisannexincludesglobalhistoricalandprojecteddatabyscenarioforthefollowingfivedatasets:A.1:WorldenergysupplyA.2:WorldfinalenergyconsumptionA.3:Worldelectricitysector:grosselectricitygenerationandelectricalcapacity.A.4:WorldCO₂emissions:carbondioxide(CO2)emissionsfromfossilfuelcombustionandindustrialprocesses.A.5:Worldeconomicandactivityindicators:selectedeconomicandactivityindicators.Eachdatasetisgivenforthefollowingscenarios:(a)StatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS)[TablesA.1a.toA.5a];(b)AnnouncedPledgesScenario(APS)[TablesA.1b.toA.5b];and(c)NetZeroEmissionsby2050(NZE)Scenario[TablesA.1c.toA.5c].ThisannexalsoincludesregionalhistoricalandprojecteddatafortheSTEPSandtheAPSforthefollowingdatasets:TablesA.6–A.7:Totalenergysupply,renewablesenergysupplyinexajoules(EJ).TablesA.8–A.11:Oilproduction,oildemand,worldliquidsdemand,andrefiningcapacityandrunsinmillionbarrelsperday(mb/d).TablesA.12–A.13:Naturalgasproduction,naturalgasdemandinbillioncubicmetres(bcm).TablesA.14–A.15:Coalproduction,coaldemandinmilliontonnesofcoalequivalent(Mtce).TablesA.16–A.22:Electricitygenerationbytotalandbysource(renewables,solarphotovoltaics[PV],wind,nuclear,naturalgas,coal)interawatt-hours(TWh).TablesA.23–A.26:Totalfinalconsumptionandconsumptionbysector(industry,transportandbuildings)inexajoules(EJ).TablesA.27–A.28:Hydrogendemand(PJ)andthelow-emissionshydrogenbalanceinmilliontonnesofhydrogenequivalent(MtH2equivalent).TablesA.29–A.31:Totalcarbondioxide(CO₂)emissions,electricityandheatsectorsCO₂emissions,finalconsumptioninmilliontonnesofCO₂emissions(MtCO₂).TablesA.6toA.31cover:World,NorthAmerica,UnitedStates,CentralandSouthAmerica,Brazil,Europe,EuropeanUnion,Africa,MiddleEast,Eurasia,Russia,AsiaPacific,China,India,JapanandSoutheastAsia.Thedefinitionsforregions,fuelsandsectorsareinAnnexC.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojections259IEA.CCBY4.0.Abbreviations/acronymsusedinthetablesinclude:CAAGR=compoundaverageannualgrowthrate;CCUS=carboncapture,utilisationandstorage;EJ=exajoule;GJ=gigajoule;GW=gigawatt;MtCO₂=milliontonnesofcarbondioxide;TWh=terawatt-hour.UseoffossilfuelsinfacilitieswithoutCCUSisclassifiedas“unabated”.Bothinthetextofthisreportandintheseannextables,roundingmayleadtominordifferencesbetweentotalsandthesumoftheirindividualcomponents.Growthratesarecalculatedonacompoundaverageannualbasisandaremarked“n.a.”whenthebaseyeariszeroorthevalueexceeds200%.Nilvaluesaremarked“-”.BoxA.1providesdetailsonwheretodownloadtheWorldEnergyOutlook(WEO)tablesinExcelformat.Inaddition,BoxA.1liststhelinksrelatingtothemainWEOwebsite,documentationandmethodologyoftheGlobalEnergyandClimateModel,investmentcosts,policydatabasesandrecentWEOSpecialReports.DatasourcesTheGlobalEnergyandClimateModelisaverydata-intensivemodelcoveringthewholeglobalenergysystem.DetailedreferencesondatabasesandpublicationsusedinthemodellingandanalysismaybefoundinAnnexE.Theformalbaseyearforthisyear’sprojectionsis2021,asthisisthemostrecentyearforwhichacompletepictureofenergydemandandproductionisavailable.However,wehaveusedmorerecentdatawhereveravailable,andweincludeour2022estimatesforenergyproductionanddemandinthisannex.Estimatesfortheyear2022arebasedontheIEACO2Emissionsin2022reportinwhichdataarederivedfromanumberofsources,includingthelatestmonthlydatasubmissionstotheIEAEnergyDataCentre,otherstatisticalreleasesfromnationaladministrations,andrecentmarketdatafromtheIEAMarketReportSeriesthatcovercoal,oil,naturalgas,renewablesandpower.Investmentestimatesincludetheyear2022data,basedontheIEAWorldEnergyInvestment2023report.Historicaldataforgrosspowergenerationcapacity(TableA.3)aredrawnfromtheS&PGlobalMarketIntelligenceWorldElectricPowerPlantsDatabase(March2023version)andtheInternationalAtomicEnergyAgencyPRISdatabase.Definitionalnote:EnergysupplyandtransformationtablesTotalenergysupply(TES)isequivalenttoelectricityandheatgenerationplustheotherenergysector,excludingelectricity,heatandhydrogen,plustotalfinalconsumption,excludingelectricity,heatandhydrogen.TESdoesnotincludeambientheatfromheatpumpsorelectricitytrade.SolarinTESincludessolarPVgeneration,concentratingsolarpower(CSP)andfinalconsumptionofsolarthermal.Biofuelsconversionlossesaretheconversionlossestoproducebiofuels(mainlyfrommodernsolidbioenergy)usedintheenergysector.Low‐emissionshydrogenproductionismerchantlow‐emissionshydrogenproduction(excludingonsiteproductionatindustrialfacilitiesandrefineries),withinputsreferringtototalfuelinputsandoutputstoproducehydrogen.Whilenotitemised260InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023separately,geothermalandmarine(tidalandwave)energyareincludedintherenewablescategoryofTESandelectricityandheatsectors.Whilenotitemisedseparately,non-renewablewasteandothersourcesareincludedinTES.Definitionalnote:EnergydemandtablesSectorscomprisingtotalfinalconsumption(TFC)includeindustry(energyuseandfeedstock),transportandbuildings(residential,servicesandnon-specifiedother).Whilenotitemisedseparately,agricultureandothernon-energyuseareincludedinTFC.Whilenotitemisedseparately,non-renewablewaste,solarthermalandgeothermalenergyareincludedinbuildings,industryandTFC.Aviationandshippingincludebothdomesticandinternationalenergydemand.EnergydemandfrominternationalmarineandaviationbunkersareincludedinglobaltransporttotalsandTFC.Definitionalnote:FossilfuelproductionanddemandtablesOilproductionanddemandisexpressedinmillionbarrelsperday(mb/d).TightoilincludestightcrudeoilandcondensateproductionexceptfortheUnitedStates,whichincludestightcrudeoilonly(UStightcondensatevolumesareincludedinnaturalgasliquids).Processinggainscovervolumeincreasesthatoccurduringcrudeoilrefining.Biofuelsandtheirinclusioninliquidsdemandisexpressedinenergy-equivalentvolumesofgasolineanddiesel.Naturalgasproductionanddemandisexpressedinbillioncubicmetres(bcm).Coalproductionanddemandisexpressedinmilliontonnesofcoalequivalent(Mtce).Differencesbetweenhistoricalproductionanddemandvolumesforoil,gasandcoalareduetochangesinstocks.Bunkersincludebothinternationalmarineandaviationfuels.Refiningcapacityatriskisdefinedasthedifferencebetweenrefinerycapacityandrefineryruns,withthelatterincludinga14%allowancefordowntime.Projectedshutdownsbeyondthosepubliclyannouncedarealsocountedascapacityatrisk.Definitionalnote:ElectricitytablesElectricitygenerationexpressedinterawatt-hours(TWh)andinstalledelectricalcapacitydataexpressedingigawatts(GW)arebothprovidedonagrossbasis,i.e.includesownusebythegenerator.Projectedgrosselectricalcapacityisthesumofexistingcapacityandadditions,lessretirements.Whilenotitemisedseparately,othersourcesareincludedintotalelectricitygeneration.Hydrogenandammoniaarefuelsthatcanprovidealow-emissionsalternativetonaturalgas-andcoal-firedelectricitygeneration–eitherthroughco-firingorfullconversionoffacilities.Blendinglevelsofhydrogeningas-firedplantsandammoniaincoal-firedplantsarerepresentedinthescenariosandreportedinthetables.Theelectricitygenerationoutputsinthetablesarebasedonfuelinputshares,whilethehydrogenandammoniacapacityisderivedbasedonatypicalcapacityfactor.Definitionalnote:CO2emissionstablesAIEA.CCBY4.0.TotalCO2includescarbondioxideemissionsfromthecombustionoffossilfuelsandnon-renewablewastes;fromindustrialandfueltransformationprocesses(processAnnexATablesforscenarioprojections261emissions);andfromflaringandCO2removal.CO2removalincludes:capturedandstoredemissionsfromthecombustionofbioenergyandrenewablewastes;frombiofuelsproduction;andfromdirectaircapture.Aviationandshippingincludebothdomesticandinternationalemissions.Thefirsttwoentriesareoftenreportedasbioenergywithcarboncaptureandstorage(BECCS).NotethatsomeoftheCO2capturedfrombiofuelsproductionanddirectaircaptureisusedtoproducesyntheticfuels,whichisnotincludedasCO2removal.TotalCO2capturedincludesthecarbondioxidecapturedfromCCUSfacilities,suchaselectricitygenerationorindustry,andatmosphericCO2capturedthroughdirectaircapture,butexcludesthatcapturedandusedforureaproduction.Definitionalnote:EconomicandactivityindicatorsTheemissionsintensityexpressedingrammesofcarbondioxideperkilowatt‐hour(gCO2perkWh)iscalculatedbasedonelectricity‐onlyplantsandtheelectricitycomponentofcombinedheatandpower(CHP)plants.1Primarychemicalsincludeethylene,propylene,aromatics,methanolandammonia.Industrialproductiondataforaluminiumexcludesproductionbasedoninternallygeneratedscrap.Heavy-dutytrucksactivityincludesfreightactivityofmediumfreighttrucksandheavyfreighttrucks.Aviationactivityincludesbothdomesticandinternationalflightactivity.Shippingactivityreferstointernationalshippingactivity.Abbreviationsusedinclude:GDP=grossdomesticproduct;GJ=gigajoule;m2=squaremetres;Mt=milliontonnes;pkm=passenger‐kilometres;PPP=purchasingpowerparity;tkm=tonnes‐kilometres.Definitionalnote:HydrogentablesTotalhydrogendemandincludesmerchant(oroffsite)hydrogendemandandhydrogendemandinindustryandrefineriescoveredbyonsiteproduction.Italsoincludeshydrogenusedintheproductionofhydrogen-basedfuels(ammonia,synthetichydrocarbonfuels).ThehydrogenbalancetableA.28isexpressedinmilliontonnesofhydrogenequivalent,whichmeansforhydrogen-basedfuelstheequivalentmassofhydrogenthatwouldcontaintheenergycontentofthesefuels.Hydrogendemandinend-usesectorsincludestotalfinalconsumptionofhydrogenandhydrogen-basedfuelsaswellashydrogendemandinindustrycoveredbyonsiteproductionwithinindustrialfacilities.Low-emissionshydrogentradeasashareofproductionrepresentsthepercentageofproducedlow-emissionshydrogen(includingmerchanthydrogenandthatwhichisproducedonsiteinindustryandrefining)whichisexportedfromtheregionashydrogenorasanenergyproduct.IEA.CCBY4.0.1Toderivetheassociatedelectricity‐onlyemissionsfromCHPplants,weassumethattheheatproductionofaCHPplantis90%efficientandtheremainderofthefuelinputisallocatedtoelectricitygeneration.262InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023AnnexAlicencingSubjecttotheIEANoticeforCC-licencedContent,thisAnnexAtotheWorldEnergyOutlook2023islicensedunderaCreativeCommonsAttribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike4.0InternationalLicence.IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA263Energysupply:WorldBacktocontentspageSTEPSTSaTEbPSleASTE.1PSa:SWTEoPSrldSTeEnPSergSTyEPsSupSpTElPyS828Energysupply:WorldStatedPoliciesScenario(EJ)Shares(%)CAAGR(%)2022to:201020212022203020352040205020222030205062463266867869272520302050Totalenergysupply541717512015017822710010010057233549701218310.70.5Renewables43781927334213106.04.0151618192023136178.8Solar1333544485157233126.34467896781.61.3Wind11123581113.01.72424191818160014.42.7Hydro123129374043484327.76.7146144148145143142567-3.0-1.4Modernsolidbioenergy231112232322202.91.81821871951911871860000.3-0.0Modernliquidbioenergy2313238404141302926106.21671701471301191015660.5-0.0Moderngaseousbioenergy10000012722142.30.9244247263275291321000-1.8-1.8Traditionaluseofbiomass25394177102126166231345193143621001001000.80.9Nuclear3078192733421729528.05.11516181920232719209.7Unabatednaturalgas11599141617213713126.3--00006771.61.3NaturalgaswithCCUS0--00004564.82.9312937404348-00n.a.n.a.Oil173575755514949-00n.a.n.a.--00001214152.91.8Non-energyuse25885443232115-0.5-0.610811089756652-00n.a.n.a.Unabatedcoal153000000321-5.1-3.3646568696973453416-2.7-2.6CoalwithCCUS-000291556889100.70.4Electricityandheatsectors2001001001000012343.61.9Renewables20001123100100100--0011SolarPV0Wind1Hydro12Bioenergy4Hydrogen-Ammonia-Nuclear30Unabatednaturalgas47NaturalgaswithCCUS-Oil11Unabatedcoal91CoalwithCCUS-Otherenergysector50Biofuelsconversionlosses-Low-emissionshydrogen(offsite)Productioninputs-100100100n.a.n.a.1001001008325Productionoutputs-n.a.n.a.-2729Forhydrogen-basedfuels-IEA.CCBY4.0.264InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Totalfinalconsumption:WorldBacktocontentspageTTSaaTEbbPSlleeASAT.E.2P2Saa::WSWTEooPSrrllddSfTfiiEnnPaSalleeSTnnEePeSrrggyySTcEcPoSomnsSsTuuEmPmSppttiioonn828Totalfinalconsumption:WorldCAAGR(%)2022to:StatedPoliciesScenario(EJ)Shares(%)20302050Totalfinalconsumption20102021202220302035204020502022203020501.10.7Electricity2.52.1Liquidfuels3834364424824965095361001001000.90.26487891081211351592022304.42.7Biofuels154168172186184183185393934n.a.n.a.Ammonia2n.a.n.a.Syntheticoil24467891100.80.2Oil---0000-0-1.20.6Gaseousfuels---------331311Biomethane1511641681801771751763837165822Hydrogen5872717880828516161n.a.n.a.Syntheticmethane00011240001.10.4Naturalgas-00001100--0.4-0.3Solidfuels---------15-0.6-0.0Solidbioenergy57727076787978161616-0.2-0.6Coal95929390888784211971.10.3Heat383940383939409881.40.8Industry56525251494744121131.81.4Electricity12151516161616332.41.0Liquidfuels1431671671871942012071001001002.41.0Oil273738444750562323271.61.0Gaseousfuels293332394142431921211612Biomethane293332394142431921216120Hydrogen243130343638391818191.50.7Unabatednaturalgas0000012001118.5NaturalgaswithCCUS-0000000000.60.1Solidfuels243130343536371818182.21.5Modernsolidbioenergy-0000000000.2-0.4Unabatedcoal585859626262603533299.77.2CoalwithCCUS81011131415177781.00.3Heat494747484746432826212.21.0Chemicals-0000000000.50.1Ironandsteel57788884440.40.0Cement384848576062632931310.5-0.0Aluminium3137353637373721201891212121212127765777777443IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA265Totalfinalconsumption:TTaabblleeAA..22aa::WWoorrllddffiinnaalleenneerrggyyccoomnssuummppttiioonn((ccoonnttiinnuueedd))Totalfinalconsumption:WorldStatedPoliciesScenario(EJ)Shares(%)CAAGR(%)2022to:Transport2010202120222030203520402050202220302050Electricity20302050Liquidfuels10211211612712913113910010010011258111514111.10.6Biofuels84158.6Oil97106110117115114117949260.80.2Gaseousfuels244677845784.32.6Biomethane50.60.1Hydrogen95102105111108106108918701.11.1Naturalgas45566775519.77.4Road00000010045722Passengercars-00001100680.60.2Heavy-dutytrucks455566544280.60.2Aviation28-0.4-0.5Shipping768789939292947673172.01.4Buildings384445434140383834115.52.7Electricity2126273133353923251.01.2Liquidfuels11111719202410131000.60.7Biofuels10911121313161010502.32.0Oil117111331391421471591001005-1.3-1.5Gaseousfuels35131465562688035400n.a.n.a.Biomethane1345131210105-1.4-1.5Hydrogen13999200.70.2Naturalgas--0000-011411Solidfuels13-131210991090n.a.n.a.Modernsolidbioenergy271331333332322324190.6-0.0Traditionaluseofbiomass3111014-2.5-1.3Coal0000000042.51.2Heat-0-003130-2310-3.0-1.4Residential26-303232242323190-7.2-8.6Services35313226255624451.30.44324551816314670.00.425424191810182331.71.1624421883664788981065688379394964953713234933945472938IEA.CCBY4.0.266InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Electricitysector:WorldBacktocontentspageSTEPSTTaaSTbbEPlleSeAAS.T.33EaPaS::WWSTooErPrlSlddeeSTlleEePcScttrriicScTiEitPtyySsseeSTccEtPtoSorr828Electricitysector:WorldCAAGR(%)2022to:StatedPoliciesScenario(TWh)Shares(%)20302050Totalgeneration20102021202220302035204020502022203020502.72.2Renewables8.85.421533283462903335802404944541853985100100100209.7SolarPV42097964859916915230512872137973304770126.3Wind1023129154058657119611722015321.61.3Hydro32186521255229750211801415225.73.4Bioenergy3424299437849815293927571412n.a.n.a.ofwhichBECCS345610731241555463511531411CSP309666687141017462307.15.4Geothermal--45-012418Marine-4691550012.81.7Nuclear21516175247161322000n.a.n.a.Hydrogenandammonia68961016203174390083319FossilfuelswithCCUS113351366544939902514CoalwithCCUS275628101225938864353-00n.a.n.a.NaturalgaswithCCUS-26827308291000-1.7-1.6Unabatedfossilfuels--4145990000-2.8-2.6Coal-1-3162229-0210.2-0.2Naturalgas-111540613593376161439-5.2-3.3Oil14479-1833369731256811373362311866917456-6611622261454949221814847102471763646239860676150219636526104273562746836500709StatedPoliciesScenario(GW)Shares(%)CAAGR(%)2022to:Totalcapacity2010202120222030203520402050202220302050Renewables2030205051878230864314168179232132825956100100100SolarPV13333292362986111194914965191204261746.44.0Wind11454699717412639133349116.1Hydro39925206427479500101515199.0Bioenergy181827902157116813242387416118115.3ofwhichBECCS1027136013921801202821.51.4CSP741592322722204.13.1Geothermal16811311393-00n.a.n.a.Marine---162911000119.4Nuclear167273746850007.45.3Hydrogenandammonia10153947630021715FossilfuelswithCCUS011518365301.81.4CoalwithCCUS4034131482521-00n.a.n.a.NaturalgaswithCCUS--4178175576220004122Unabatedfossilfuels-0-21224190003218Coal-00162231-015n.a.n.a.Naturalgas--016111352325-0.1-0.6Oil34394480-111826159-0.6-1.8Batterystorage16142200453544984364221511.20.71389185422362126195642163800529-4.2-3.0436426187520712139179513631437151274232185225945301269552104723617815312352IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA267CO₂emissions:WorldBacktocontentspageSTEPSTTaabbSTlleEePSAA..44aaST::EPWWSoorldSTECPSO2eSTmEPiSssionSTsEPSSTEPSSTEPS828CO₂emissions:Worl2dStatedPoliciesScenario(MtCO₂)CAAGR(%)2022to:201020212022203020352040205020302050TotalCO₂32877365893693035125330943165729696-0.6n.a.Combustionactivities(+)306243363434042321623014128708267821384615104153301307611594105488861-0.7-0.9Coal10545106831096311155107731048310378Oil6052757774997705756374677339-2.0-1.9NaturalgasBioenergyandwaste1812692512272112102040.2-0.2Otherremovals(-)-1221324580Biofuelsproduction-1223330.3-0.1Directaircapture---18294377-1.2-0.71482212302107299696821710876870973956495512637155963933383012305.11.632013071287827792734n.a.n.a.149129119122126Electricityandheatsectors125111459815541640160215771545-2.3-2.1Coal8946106462029321046206862036319950Oil43524263410039583646-2.7-2.7Naturalgas828574981510206990396729669Bioenergyandwaste2623322735003788385538773804-5.1-3.3OtherenergysectorFinalconsumption11415110298938878-0.5-0.6Coal1438153089989540960295839225Oil186682019113301461147214581378-1.8-0.6Naturalgas4699435526232685267526502547Bioenergyandwaste90879552241825222547255624980.7-0.0Industry284235662652752722702450.5-0.1Chemicals6611878748282809279548060Ironandsteel8324918559645940562953695165-0.3-0.6Cement1201132929752716241421771935Aluminium20832733181220502128220323420.5-0.1Transport191625141195131314151583Road79210981.00.31852618559049179432307Passengercars7014759929792802258024271402-0.4-0.9Heavy-dutytrucks521658471997179116381526Aviation2609293098310129050.70.1Shipping14891766942901Buildings224891.20.1Residential754661421163751401Services7978271972760.3-0.128912973196120130.50.19299590.4-0.30.60.1-0.0-0.5-1.1-1.51.60.95.32.50.70.9-0.8-0.9-1.4-1.30.4-0.3TotalCO₂removals-23915TotalCO₂captured1541148.4Includesindustrialprocessandflaringemissions.Includesindustrialprocessemissions.IEA.CCBY4.0.268InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Indicatorsandactivity:WorldBacktocontentspageSTEPSSTEPSSTEPSSTEPSSTEPSSTEPSSTEPSSTEPS828TableA.5a:WorldeconomicandactivityindicatorsIndicatorsandactivity:WorldStatedPoliciesScenarioCAAGR(%)2022to:201020212022203020352040205020302050Indicators69677884795085208853916196810.90.7Population(million)114463158505163734207282238066270050339273GDP(USD2022billion,PPP)205963.02.6GDPpercapita(USD2022,PPP)164292010424329268922947935044TES/GDP(GJperUSD1000,PPP)4.73.93.93.22.92.62.12.11.9TFC/GDP(GJperUSD1000,PPP)3.22.62.62.22.01.81.5-2.2-2.1-1.8-1.8CO₂intensityofelectricity528464460303230184131-5.1-4.4generation(gCO₂perkWh)Industrialproduction(Mt)51571371987794198910472.51.3Primarychemicals1435196018782074217322702448Steel32804374415844714628474648461.31.0CementAluminium621051081231331451650.90.5TransportPassengercars(billionpkm)1.71.5Heavy-dutytrucks(billiontkm)Aviation(billionpkm)189842567926535318043582739760464112.32.0Shipping(billiontkm)23364294823047938977443444999161107Buildings6025121981397316061203883.12.5Households(million)49233673124272148064170250196465279868Residentialfloorarea(millionm²)771011158309.24.4Servicesfloorarea(millionm²)2.22.917982175220824392579271529631.21.11532191946911980902270392472622681303101093926253415546241.71.6638916919774143827642.01.5IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA269Energysupply:STEPSSTEPSSTEPSAPSAPSAPSAPS828TableA.1b:WorldenergysupplyEnergysupply:AnnouncedPledgesScenario(EJ)Shares(%)CAAGR(%)2022to:201020212022203020352040205020222030205062463262861361262320302050Totalenergysupply541717514219524532710010010057274870106122352-0.1-0.1Renewables43782234466614178.25.4151618202327111910Solar1333551596574144148.044912141423121.91.9Wind111468136824.82.724248765122114.3Hydro12312938455259011168.41461441301119671419-13-5.6Modernsolidbioenergy23113681356113.42.518218717715513310223212-1.2-2.5Modernliquidbioenergy23132363636340116261216717012789643430286-0.7-2.1Moderngaseousbioenergy100046115651.70.324424725827330636627202-3.6-5.6Traditionaluseofbiomass2539418813017424800472645234059871001001000.51.4Nuclear3078223446661734689.96.615161820232729242211Unabatednaturalgas11599162126343918148.0--01236771.91.9NaturalgaswithCCUS0--00124697.04.7312938455259-01n.a.n.a.Oil173575750413525-00n.a.n.a.--01121215163.42.5Non-energyuse2588432223197-1.7-2.910811075483317-00n.a.n.a.Unabatedcoal153000347320-7.8-5.364656565667245295-4.7-6.4CoalwithCCUS-002572956121618171001000.10.4Electricityandheatsectors200100004915321001009.84.0Renewables2000261123100--12410SolarPV0Wind1Hydro12Bioenergy4Hydrogen-Ammonia-Nuclear30Unabatednaturalgas47NaturalgaswithCCUS-Oil11Unabatedcoal91CoalwithCCUS-Otherenergysector50Biofuelsconversionlosses-Low-emissionshydrogen(offsite)Productioninputs-100100100n.a.n.a.10010010011635Productionoutputs-n.a.n.a.-2746Forhydrogen-basedfuels-IEA.CCBY4.0.270InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Totalfinalconsumption:TSaTEbPSleSTEPSSWTEoPSrldAfPiSnaleAPnSergAyPSconAsPuSmption828Totalfinalconsumption:WorldA.2b:CAAGR(%)2022to:AnnouncedPledgesScenario(EJ)Shares(%)20302050Totalfinalconsumption20102021202220302035204020502022203020500.2-0.1Electricity2.62.5Liquidfuels3834364424514424334291001001000.2-1.3648789109125143176202441114.3Biofuels154168172175160143118393928n.a.n.a.Ammonia43n.a.n.a.Syntheticoil249121414121-0.2-1.9Oil---0112-01-0.0-0.5Gaseousfuels---0013-0232612Biomethane1511641681651471273837148631Hydrogen5872717167649916161n.a.n.a.Syntheticmethane00023461002-0.5-1.7Naturalgas-0012400--2.5-2.1Solidfuels------6--10-3.4-0.9Solidbioenergy57727067615410161512-1.8-3.5Coal959293766860211770.1-1.1Heat383940303030-9740.90.2Industry56525245373044121032.72.3Electricity12151515141351331.4-0.2Liquidfuels143167167179180179311001001001.3-0.3Oil273738475360192326400.4-0.2Gaseousfuels293332363634111920182913Biomethane2933323635331751920179533Hydrogen243130313131711817160.0-1.4Unabatednaturalgas000112310022316NaturalgaswithCCUS-0001230002-0.3-1.5Solidfuels243130302826281817113.12.0Modernsolidbioenergy-00011002-1.3-3.9Unabatedcoal58585957524733532223523CoalwithCCUS8101114161737811-0.8-2.2Heat49474743352820282491.60.5Chemicals-000123002-0.0-0.5Ironandsteel57776539442-0.0-0.2Cement384848555656192930310.2-0.7Aluminium3137353534331521201791212121212477657777744435531116IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA271Totalfinalconsumption:TableA.2b:Worldfinalenergyconsumption(continued)Totalfinalconsumption:WorldAnnouncedPledgesScenario(EJ)Shares(%)CAAGR(%)2022to:Transport2010202120222030203520402050202220302050Electricity20302050Liquidfuels102112116122116110106100100100112611182815270.6-0.3Biofuels8769651811Oil9710611011110012129491110.2-1.7Gaseousfuels2449117351474810.03.9Biomethane88699-0.4-2.6Hydrogen9510210510250091840-0.61.9Naturalgas4555027546165.8Road00001320027830Passengercars-000476690065-2.2-3.2Heavy-dutytrucks45548232274426-0.0-0.9Aviation36292927-1.0-1.8Shipping768789883020227673211.20.3Buildings384445411810113834105.22.5Electricity212627301123240.4-0.2Liquidfuels1111171171221014100-1.0-0.3Biofuels109111211962711010581.71.6Oil1171113312256751001004-2.2-3.2Gaseousfuels35131465290035430n.a.n.a.Biomethane13451311075104-2.2-3.2Hydrogen1392319915-0.6-1.7Naturalgas--02623-023214Solidfuels13-13111001090n.a.n.a.Modernsolidbioenergy2713313002014232412-1.0-2.6Traditionaluseofbiomass3123121119-7.6-3.8Coal00115660057.01.2Heat-0-0765-234-13-5.6Residential26-302870023140-10-11Services3531321717724660.9-0.243247876793764-1.8-0.6254248784144181360.80.4624424136647856683793817134349339422938IEA.CCBY4.0.272InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Electricitysector:STEPSTaSTbElPeSSTEPSAPSAPSAPSAPS828A.3b:WorldelectricitysectorElectricitysector:AnnouncedPledgesScenario(TWh)Shares(%)CAAGR(%)2022to:Totalgeneration2010202120222030203520402050202220302050Renewables2030205021533283462903336370429335171066760100100100SolarPV420979648599192952879538551550573053822.93.0Wind10231291639011240162962429741836116.9Hydro3218652125620895241270118432717282211Bioenergy342429943785071565362847432151411148.0ofwhichBECCS345613141736218430052451.91.9CSP309666687018.45.4Geothermal--32158302538-02n.a.n.a.Marine-8427858111010112316Nuclear2151621733544800010.07.0Hydrogenandammonia689610111295667701083618FossilfuelswithCCUS113496408647011139013.42.5CoalwithCCUS275628101782293445301-01n.a.n.a.NaturalgaswithCCUS-2682483285666060017029Unabatedfossilfuels--222364099490005428Coal-1-2792157710-377n.a.n.a.Naturalgas-11133569407745823961192-3.4-4.6Oil14479-1697642492932475936175-4.9-6.6866917456-60284896431415342210-0.9-2.64847102471763635226221230802-8.4-5.59636526104271446836500709AnnouncedPledgesScenario(GW)Shares(%)CAAGR(%)2022to:Totalcapacity2010202120222030203520402050202220302050Renewables2030205051878230864315285203322519532100100100100SolarPV13333292362997861442618893253684264797.44.8Wind1145537786481178716041133550137.2Hydro399252420341843375879101618219.9Bioenergy181827902162018041991230416117136.9ofwhichBECCS1027136013922221.91.8CSP74159300407524706007.65.3Geothermal1688325694-01n.a.n.a.Marine---29861652950001914Nuclear1675167100000117.0Hydrogenandammonia1015341223440322715FossilfuelswithCCUS011555876777695012.22.2CoalwithCCUS4034131134174195-01n.a.n.a.NaturalgaswithCCUS--417497711212060007030Unabatedfossilfuels-0-3150881530005329Coal-008213453-288n.a.n.a.Naturalgas--0437253289243252133-0.9-2.2Oil34394480-51749147491126124-1.2-3.2Batterystorage16142200453517431613137122200.2-1.113891854223642252342021505510-4.9-3.64364261875203613772029312114116127423190545283725IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA273CO₂emissions:STEPSSTEPSSTEPSAPSeAmPSissionAPsSAPS828TableA.4b:WorldCO2CO₂emissions:2AnnouncedPledgesScenario(MtCO₂)CAAGR(%)2022to:201020212022203020352040205020302050TotalCO₂32877365893693030769242891921712043-2.3n.a.Combustionactivities(+)30624336343404228115219661737510968138461510415330111747711-2.4-4.0Coal1054510683109631000456262967Oil849169694852-3.9-5.7Naturalgas6052757774996764572548843516Bioenergyandwaste181269251173-104-368-1.1-2.9Otherremovals(-)-1210039Biofuelsproduction-1278158256345-1.3-2.7Directaircapture---221302202842861-4.5n.a.148221059736108767388719730046721467753521712596310327862203201279723412822861901427n.a.n.a.1491021982-263Electricityandheatsectors125111459815541215-0-4.1-5.5Coal8946106462029318876898-98121Oil82843523695161555398952-4.7-6.4Naturalgas2623574981592792958133241238Bioenergyandwaste114322735003306793722924593-7.8-5.3Otherenergysector1438290865441824Finalconsumption1866815110272402496-1.7-2.8Coal46991530899885007398-5-97Oil90872019113301289113061383826-4.7n.a.Naturalgas28424355262324742153909Bioenergyandwaste6695522418229920411805501-3.0-8.7Industry8324356622617161119120126525365051731143-0.9-2.9Chemicals20831187874755545395370Ironandsteel19169185596454231902359463-2.0-4.4Cement185132929752466173814043786Aluminium7014273318121864113115082337-0.7-2.7Transport5216251411296701097Road26097921963543844-0.7-2.31489261855803126015781078Passengercars754759929792475702990-4.3n.a.Heavy-dutytrucks797584719971605587979Aviation28912930983289384-0.7-3.0Shipping1961176686911785171176Buildings92922061683-0.4-3.4Residential66142128493Services827441-0.7-3.0297384820133730-0.6-2.6959-0.6-5.0-0.5-2.6-1.2-3.3-2.3-4.40.4-1.84.50.8-0.8-2.8-2.3-3.3-2.7-3.8-1.5-2.4TotalCO₂removals-27225TotalCO₂captured15413417Includesindustrialprocessandflaringemissions.Includesindustrialprocessemissions.IEA.CCBY4.0.274InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Indicatorsandactivity:TableSATE.P5Sb:WSToErPlSdecSToEPnSomiAcPSandaAPcStivityAiPnSdicatAoPSrs828Indicatorsandactivity:AnnouncedPledgesScenarioCAAGR(%)2022to:201020212022203020352040205020302050Indicators69677884795085208853916196810.90.7Population(million)114463158505163734207282238066270050339273GDP(USD2022billion,PPP)1642920104205963.02.6GDPpercapita(USD2022,PPP)24329268922947935044TES/GDP(GJperUSD1000,PPP)4.73.93.93.02.62.31.82.11.9TFC/GDP(GJperUSD1000,PPP)3.22.62.62.11.81.61.2-3.0-2.6CO₂intensityofelectricity5284644602551438736generation(gCO₂perkWh)-2.6-2.6Industrialproduction(Mt)-7.1-8.7PrimarychemicalsSteel5157137198549029339522.21.0Cement1435196018782030205820812123Aluminium32804374415843754407440043931.00.4TransportPassengercars(billionpkm)621051081221291361490.60.2Heavy-dutytrucks(billiontkm)Aviation(billionpkm)1.51.2Shipping(billiontkm)Buildings189842567926535311743439937988449002.01.9Households(million)23364294823047938198435044921860578Residentialfloorarea(millionm²)492336736025120971378315890203132.92.5Servicesfloorarea(millionm²)771011158301242721479481701081962952798859.14.42.22.917982175220824392579271529631.21.11532191946911980902270392472622681303101093926253415546241.71.6638916919774143827642.01.5IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA275Energysupply:STEPSTSaTEbPSleASTE.P1Sc:NWZEorldNeZEnergNyZEsupNpZEly828Energysupply:CAAGR(%)2022to:NetZeroEmissionsby2050Scenario(EJ)Shares(%)203020502010202120222030203520402050202220302050-1.2-0.6624632573535528541Totalenergysupply5417175166241306385100100100106.0573566971381229712311Renewables43782543618426169.015162024273016162.92.3Solar13335556571731455.82.644111313112313133.3Wind1117911156102229.02424----123n.a.n.a.Hydro1231294355636701-5.03.01461441136840144-12-3.0-8.1Modernsolidbioenergy23116913185833513182187148110794223203-2.8-5.2Modernliquidbioenergy23132353433300181.3-0.1167170934316330266-7.3-14Moderngaseousbioenergy1002710125618727244247256277319393271620.41.7Traditionaluseofbiomass25394110316722830600127.4452956801121001001002612Nuclear307825436184174078169.0151620242730211292.92.3Unabatednaturalgas1159917243036310217.34.9--2456688n.a.n.a.NaturalgaswithCCUS0--1222469n.a.n.a.312943556367-125.03.0Oil17357574925111-01-1.7-13--0223121717n.a.n.a.Non-energyuse2588210023190-17-2310811053160--01-8.9n.a.Unabatedcoal153002567310102296465646470784521--0.20.7CoalwithCCUS-0125614161612100100112.6Electricityandheatsectors200100009203354100100n.a.n.a.Renewables2000614233910014438--21017n.a.n.a.SolarPV05Wind1Hydro12Bioenergy4Hydrogen-Ammonia-Nuclear30Unabatednaturalgas47NaturalgaswithCCUS-Oil11Unabatedcoal91CoalwithCCUS-Otherenergysector50Biofuelsconversionlosses-Low-emissionshydrogen(offsite)Productioninputs-100100100100100100Productionoutputs--3143Forhydrogen-basedfuels-IEA.CCBY4.0.276InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Totalfinalconsumption:STEPSSTEPSSTEPSNZENZENZENZE828TableA.2c:WorldfinalenergyconsumptionCAAGR(%)2022to:Totalfinalconsumption:World20302050NetZeroEmissionsby2050Scenario(EJ)Shares(%)-1.1-0.93.02.6Totalfinalconsumption2010202120222030203520402050202220302050-1.7-3.6ElectricityLiquidfuels383436442406379360343100100100133.3648789113133154183202853n.a.n.a.Biofuels1541681721501209462393718n.a.n.a.Ammonia243-2.4-4.9Syntheticoil411131311131-1.8-2.0Oil---1224-024213Gaseousfuels---0126-01211333Biomethane1511641681381047641383412n.a.n.a.Hydrogen5872716152454116152-3.2-5.3Syntheticmethane0004668015-4.8-3.4Naturalgas-002581601--6.1-1.2Solidfuels---------4-3.9-6.9Solidbioenergy57727054412915161310-2.1-3.2Coal95929363544535211580.6-0.2Heat383940242626289624.22.7Industry565252382718712920.7-1.0Electricity121515121196330.5-1.2Liquidfuels143167167175173169159100100100-0.1-1.3Oil273738526270792330494315Gaseousfuels2933323432292419191513736Biomethane29333234312823191914-1.5-5.3Hydrogen243130302825211817134618Unabatednaturalgas0001234013-1.5-2.5NaturalgaswithCCUS-0012450134.22.5Solidfuels243130272116618154-3.5-10Modernsolidbioenergy-0012350137125Unabatedcoal58585952453829353018-3.9-6.1CoalwithCCUS810111518202279141.60.2Heat494747362415228201-0.6-1.0Chemicals-001245003-0.4-0.7Ironandsteel5775431431-0.4-1.1Cement38484854555551293132Aluminium3137353432302621191791212121111107765777665443IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA277Totalfinalconsumption:TableA.2c:Worldfinalenergyconsumption(continued)Totalfinalconsumption:WorldNetZeroEmissionsby2050Scenario(EJ)Shares(%)CAAGR(%)2022to:Transport2010202120222030203520402050202220302050Electricity20302050Liquidfuels10211211610589797610010010011281525381851-1.3-1.5Biofuels694926352312Oil971061109212118948811Gaseousfuels244105533841010-2.2-5.0Biomethane95814511917715122.6Hydrogen41021055540Naturalgas055000014-3.3-8.9Road-0002410000-1.92.7Passengercars40012104162Heavy-dutytrucks7655360524776320185.1Aviation3887742217153871299832Shipping21448932262422233020-5.6-11Buildings11264527141415102613-2.2-2.2Electricity10927151010101014-4.1-3.7Liquidfuels117111111928989100111000.2-0.8Biofuels351110051556235100703.51.2Oil1313113348531104810.1-0.4Gaseousfuels-45469000-90-3.4-1.4Biomethane131313053110010.51.1Hydrogen279151052395-5.1-8.5Naturalgas0--223330223n.a.n.a.Solidfuels-13132000-20-5.2-9.5Modernsolidbioenergy263131011502300-4.1-6.5Traditionaluseofbiomass35019866241965314Coal409866396n.a.n.a.Heat25--8--188--5.8-22Residential63130-00-3-0-14-6.0Services6323216605158.41.0834475957571765n.a.n.a.34242465333158296535-14-2644353135-0.5-1.777-4.4-1.79393-1.3-0.83839IEA.CCBY4.0.278InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Electricitysector:STEPSTaSTbEPleSAS.T3EcPS:WNoZErldeNlZeEctricNZiEtyseNcZEtor828Electricitysector:CAAGR(%)2022to:NetZeroEmissionsby2050Scenario(TWh)Shares(%)20302050Totalgeneration20102021202220302035204020502022203020503.53.5Renewables137.7215332834629033382074742759111768381001001002612SolarPV42097964859922532367395045968430305989169.0Wind10231291817715439222413123721412.92.3Hydro32186521257070119231682623442419318.45.5Bioenergy342429943785507653071411n.a.n.a.ofwhichBECCS3456131318857435822515343118CSP3096666872396305621157.9Geothermal--65300-024419Marine-1394144716440014.92.9Nuclear215163065088311486010n.a.n.a.Hydrogenandammonia6896101193966200810530FossilfuelswithCCUS11393649526786291029728CoalwithCCUS2756281013737455583123-11n.a.n.a.NaturalgaswithCCUS-268222068110286015011-5.7-15Unabatedfossilfuels--1564558471161000-8.8n.a.Coal-1-64226547996-00-1.1-12Naturalgas-111106642413016446129--19-23Oil14479-149881379112135336130866917456-59432834158221604847102471763613528-209636526104271119-683650015870921NetZeroEmissionsby2050Scenario(GW)Shares(%)CAAGR(%)2022to:Totalcapacity2010202120222030203520402050202220302050Renewables2030205051878230864316180230672935436956100100100SolarPV133332923629110081746023331302754268828.25.3Wind11456101104301430318753133851157.9Hydro39925274243221017212311Bioenergy181827902176520545797761616117157.9ofwhichBECCS102713601392231326122223.02.3CSP7415929642607.35.2Geothermal1681559541688-01n.a.n.a.Marine---48134871140002716Nuclear1674878251427000168.0Hydrogenandammonia1015816991290023416FossilfuelswithCCUS011527485313.32.9CoalwithCCUS4034131541688916-11n.a.n.a.NaturalgaswithCCUS--41712936781342700011331Unabatedfossilfuels-0-5014144724100010429Coal-00203153-02n.a.n.a.Naturalgas--036951318952211-3.5-5.6Oil34394480-14468922692-5.2-7.6Batterystorage161422004535342324537224222110-0.9-3.9138918542236145791017106115111-7.8-8.243642618751746140239164818127423220141548419945101819491088752841IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA279CO₂emissions:STEPSSTEPSSTEPSNZEeNmZEissionNZsENZE828TableA.4c:WorldCO2CO₂emissions:2NetZeroEmissionsby2050Scenario(MtCO₂)CAAGR(%)2022to:201020212022203020352040205020302050TotalCO₂32877365893693024030133756471--5.2n.a.Combustionactivities(+)30624336343404221958120175820655138461510415330817335411200171-5.3-13Coal1054510683109633219824Oil791053251780358-7.6-15Naturalgas60527577749957953327-379-698Bioenergyandwaste181269251-176933-4.0-8.8Otherremovals(-)-1280523312Biofuelsproduction-12167348227621-3.2-10Directaircapture---18629598162-275-13n.a.148226941121108762854420782581131545237859651566046721320145-257-3741351401108-198n.a.n.a.1492781-13862411088Electricityandheatsectors125111459815541142-7.3n.a.Coal89461064620293413222989138Oil8284352782103501036711-8.9-20Naturalgas2623574981515187-93173Bioenergyandwaste11432273500298319713222-205-17-23Otherenergysector143873984993521440Finalconsumption1866815110225431718103245-1.7-12Coal469915308998875233Oil908720191133043-26107-15n.a.Naturalgas28424355262371585111243079Bioenergyandwaste6695522418115014918-8.2n.a.Industry832435662118850403578120126519111584856236-3.6-9.9Chemicals20831187874134355437Ironandsteel191691855964218313178-4.6-12Cement185132929755992172463208Aluminium70142733181242134062326112-3.5-9.0Transport521625141752271813754Road2609792161048-3.9-1014892618559169956Passengercars7547599297993212843724-10n.a.Heavy-dutytrucks797584719976951710Aviation2891293098317417446040-2.8-10Shipping196117661189495Buildings9292552971-1.8-11Residential66142675Services827234296-2.6-8.3297310242013632-2.9-129592421-2.4-12-3.4-8.9-4.2-11-6.4-14-1.5-8.02.0-4.7-2.6-7.0-6.5-13-6.3-12-7.0-16TotalCO₂removals-28528TotalCO₂captured15414919Includesindustrialprocessandflaringemissions.Includesindustrialprocessemissions.IEA.CCBY4.0.280InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Indicatorsandactivity:TableSATE.P5Sc:WSToErPlSdecSToEPnSomiNcZEandaNZcEtivityNiZnEdicatNoZErs828Indicatorsandactivity:NetZeroEmissionsby2050ScenarioCAAGR(%)2022to:201020212022203020352040205020302050Indicators69677884795085208853916196810.90.7Population(million)114463158505163734207282238066270050339273GDP(USD2022billion,PPP)1642920104205962689229479350443.02.6GDPpercapita(USD2022,PPP)24329TES/GDP(GJperUSD1000,PPP)4.73.93.92.82.32.01.62.11.9TFC/GDP(GJperUSD1000,PPP)3.22.62.61.91.51.31.0-4.1-3.1CO₂intensityofelectricity528464460186483-4generation(gCO₂perkWh)-3.9-3.3Industrialproduction(Mt)-11n.a.PrimarychemicalsSteel5157137198619059168782.30.7Cement1435196018781973196619581957Aluminium32804374415842644140402239340.60.1TransportPassengercars(billionpkm)621051081201281361460.3-0.2Heavy-dutytrucks(billiontkm)Aviation(billionpkm)1.41.1Shipping(billiontkm)Buildings189842567926535286083035533841416380.91.6Households(million)23364294823047938037433414903660335Residentialfloorarea(millionm²)492336736025109691141712843165452.82.5Servicesfloorarea(millionm²)771011158301242721450871650731887562652537.83.72.02.717982175220824392579271529631.21.11532191946911980902270392472622681303101093926253415546246919774143827641.71.6638912.01.5IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA281Totalenergysupply(EJ)BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.6:Totalenergysupply(EJ)Totalenergysupply(EJ)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledges2010202120222030205020302050World541.3624.0632.0667.9725.0627.7622.9NorthAmerica112.4111.6114.5108.3101.2103.487.5UnitedStates94.091.793.887.379.283.470.4CentralandSouthAmerica26.628.529.132.640.732.238.4Brazil12.213.814.016.019.216.119.1Europe89.282.178.274.566.671.257.6EuropeanUnion64.558.956.251.743.149.538.0Africa28.635.936.441.157.634.648.6MiddleEast27.134.836.442.054.640.049.7Eurasia35.242.041.640.442.538.636.9Russia28.534.634.031.931.630.727.6281.0309.5334.8289.0286.7AsiaPacific206.9276.1159.7167.7156.9157.5132.9China107.3157.642.053.773.047.660.316.615.212.514.811.3India27.939.730.337.652.036.146.0Japan20.916.7SoutheastAsia22.829.6Renewablesenergysupply(EJ)BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.7:Renewablesenergysupply(EJ)Renewablesenergysupply(EJ)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledgesTableA.720:1R0ene2w02a1bles20e22nergy20s30uppl2y05(0EJ)20302050World43.371.175.5120.0227.1142.1327.0NorthAmerica8.812.012.818.734.525.351.2UnitedStates6.69.510.115.229.120.542.5CentralandSouthAmerica7.79.510.012.919.614.928.0Brazil5.66.67.08.911.99.915.4Europe9.914.514.921.330.324.437.7EuropeanUnion7.710.811.115.822.317.926.6Africa3.75.55.88.717.39.226.3MiddleEast0.10.20.31.25.31.512.5Eurasia1.01.31.31.63.12.05.1Russia0.71.01.01.22.31.42.9AsiaPacific12.128.030.555.3115.964.1162.1China4.613.714.929.759.333.876.1India2.85.76.210.626.411.534.2Japan0.81.21.42.23.52.55.0SoutheastAsia2.85.55.88.616.710.529.7IEA.CCBY4.0.282InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Oilproduction(mb/d)BacktocontentspageStatedPolicSietsatSecdenPaorliocSietsatSecdenPaorliocieSstaStceednPaoriloicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.8:Oilproduction(mb/d)Oilproduction(mb/d)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledgesTableA.1020:1W0orld202li1quid2s02d2ema2n03d0(mb20/5d0)20302050Worldsupply85.392.697.1101.597.492.554.8Processinggains2.22.32.32.42.92.41.6Worldproduction83.190.394.899.194.590.253.1Conventionalcrudeoil67.460.262.861.358.254.929.8Tightoil0.77.58.311.110.210.36.9Naturalgasliquids12.718.319.021.219.420.113.6Extra-heavyoil&bitumen2.03.53.74.45.53.92.5Other0.30.81.01.11.21.00.3Non-OPEC49.858.760.463.953.758.329.4OPEC33.331.634.435.140.831.923.7NorthAmerica14.024.325.628.323.925.714.2CentralandSouthAmerica7.46.06.49.110.08.25.2Europe4.43.63.32.91.32.60.5EuropeanUnion0.70.50.40.40.30.30.1Africa10.27.47.16.05.75.52.9MiddleEast25.428.031.033.839.330.723.5Eurasia13.413.713.913.110.111.94.9AsiaPacific8.47.47.46.04.35.61.9OSioludtheeamstAasiand(mb/d)2.61.91.81.30.81.30.4BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTTaabblleeAA..99::OOiillddOeeilmmdemaaannnddd(m((bmm/dbb)//dd))HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledgesTableA.11:R20e10fining20c21apac20i2t2yand20r3u0ns(m205b0/d)20302050World87.193.796.5101.597.492.554.8NorthAmerica22.121.522.220.415.218.16.0UnitedStates17.817.818.316.511.714.84.6CentralandSouthAmerica5.55.35.55.76.25.12.7Brazil2.22.32.42.42.42.21.1Europe13.912.512.410.86.39.22.4EuropeanUnion10.69.49.37.83.86.51.3Africa3.33.84.04.77.74.55.4MiddleEast7.17.78.18.910.58.37.8Eurasia3.24.14.34.54.74.34.0Russia2.63.33.53.53.33.43.0AsiaPacific25.032.732.937.635.134.620.1China8.814.714.416.412.015.16.9India3.34.85.26.87.86.24.7Japan4.23.23.32.61.72.30.7SoutheastAsia4.04.64.86.06.95.53.6Internationalbunkers7.16.17.08.911.78.46.4IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA283Worldliquidsdemand(mb/d)BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSeStsatatSetcedednPaPoroliiolciciSeietsasStScecedenPnaoarirloicoSiAetasntnSecodeuPnnoacrleicodiAePsnlenSdcoegunensacrSeiocdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.10:Wo3r6l5dliqu3i6d5sdem36a5nd(m365b/d)365365Worldliquidsdemand(mb/d)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledges202120222030205020302050Totalliquids95.798.6104.4101.897.264.4Biofuels2.02.12.94.24.56.0Hydrogenbasedfuels---0.20.23.6Totaloil93.796.5101.597.492.554.8CTL,GTLandadditives0.80.90.91.10.90.2Directuseofcrudeoil1.11.00.60.30.50.2OilproductsLPGandethane91.894.6100.096.091.154.4Naphtha13.814.116.016.414.910.5Gasoline6.9Kerosene6.86.922.38.46.46.9Diesel23.624.08.716.320.37.4Fueloil28.011.16.7Otherproducts5.36.25.727.58.112.7ProductsfromNGLs26.426.712.425.22.5Refineryproducts13.66.27.7Refinerymarketshare6.06.386.410.15.18.69.910.483%11.511.145.811.512.184.513.371%80.382.583%77.884%84%80%Note:CTL=coal-to-liquids;GTL=gas-to-liquids;LPG=liquefiedpetroleumgas;RefiningcaNpGaLsc=intayturaalngadsliqruuidns.sBacktocontentspageTableA.11:Refiningcapacityandruns(mb/d)NorthAmericaRefiningcapacityandrefineryruns(mb/d)EuropeAsiaPacificTableA.11R:efRineinfgicnaipnacgitycapacityandruns(mb/dRe)fineryrunsJapanandKoreaSTEPSAPSSTEPSAPSChinaIndia2022203020502030205020222030205020302050SoutheastAsiaMiddleEast21.321.020.719.79.618.517.616.715.87.2RussiaAfrica15.814.613.313.56.412.511.08.79.73.6BrazilOther37.739.941.137.625.929.833.333.530.219.5WorldAtlanticBasin6.96.35.75.83.65.64.94.24.32.4EastofSuez18.319.819.818.410.413.716.014.714.47.15.26.37.55.94.75.16.37.45.64.15.45.56.05.55.24.14.65.54.54.410.511.912.711.28.58.59.910.48.76.27.06.76.46.44.15.54.83.84.32.13.24.04.34.03.41.82.63.32.52.32.22.22.22.11.31.92.02.11.81.15.04.95.14.93.72.32.73.12.52.1102.7105.2105.899.462.980.883.981.675.544.154.253.251.850.428.342.540.537.436.518.348.552.054.049.034.638.343.444.139.025.8IEA.CCBY4.0.284InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Naturalgasproduction(bcm)BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.12:Naturalgasproduction(bcm)Naturalgasproduction(bcm)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledges2010202120222030205020302050World3274414941384299417338612422Conventionalgas2769296828712894301627421940TightgasShalegas27429630127512218739Coalbedmethane1547958731031942854420Other77828075675422NorthAmerica-81324262411240131393611218111189418CentralandSouthAmerica16015115314415912995Europe34123924819615516247EuropeanUnion14851473422203Africa203265262283360266240MiddleEast4636606788671044818721Eurasia807998904832892764586AsiaPacific488648653664627601315NSaotutuheraastlAgsiaasdemand2(1b6cm)19518916611714777BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.13:Naturalgasdemand(bcm)Naturalgasdemand(bcm)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledges20102021202220302050203020502422WorldTableA3.31263:Na4t2u18ralg4a1s59dem4a29n9d(b4c17m3)3861NorthAmerica369835110811621107781940UnitedStates678881930868551731256CentralandSouthAmerica147160156169178152100Brazil29423233352818Europe69562754446829939093EuropeanUnion44641335830516024826Africa106174170202277182182MiddleEast395570585686849658647Eurasia573667642625644581490Russia467549520494474462370AsiaPacific57591190010341119954536ChinaIndia110369369458452410185JapanSoutheastAsia64646010716996102Internationalbunkers95989766446019150162158191254171122---82644IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA285Coalproduction(Mtce)BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.14:Coalproduction(Mtce)Coalproduction(Mtce)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledges2010202120222030205020302050World5235570961225007346543371530Steamcoal4069453348883974266933881135CokingcoalLigniteandpeat86694198888669183035030023524614610512045NorthAmerica8184414421751243582CentralandSouthAmerica7959593133253Europe33119018810758698EuropeanUnion220134136436321Africa21019620217315515144MiddleEast121111-Eurasia309430431346281307187AsiaPacific3487439147994174285636611253CoSoautlhedasetAmsiaand(Mtce)318489539449458409207BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioWorldTableA.15:Coaldemand(Mtce)NorthAmericaCoaldemand(Mtce)UnitedStatesCentralandSouthAmericaHistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledgesBrazilEurope2010202120222030205020302050EuropeanUnion5218571058075007346543371530Africa7119MiddleEast768388371110275915EurasiaTable71A6.15:3C63oalde34m1and(9M5tce)16Russia37454038442815AsiaPacific21242022271711ChinaIndia53936236822016317349JapanSoutheastAsia3612382451075088131551471461301101092735581075203237246197166187123151183191139109136963513452646314305294637631293256532393300287815632530672399602643764708670331165156155105589735122260269327427291163IEA.CCBY4.0.286InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Electricitygeneration(TWh)BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.16:Electricitygeneration(TWh)Electricitygeneration(TWh)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledges2010202120222030205020302050World21533283462903335802539853637066760NorthAmerica52335377552459458381623510986UnitedStates4354435444914805685550429013CentralandSouthAmerica1129134713891646262617233930Brazil51665667777911997791428Europe4119412639964708641949897964EuropeanUnion2955288527953256440334735441Africa6868748901203229413273859MiddleEast829124612761716295616943919Eurasia1251144614761540192315022023Russia10361158117011771376114313801448319043293851890034079AsiaPacific828513930117431652711454175898912China423685971766267256942581660510621054107610831358India972163512201709329217594498Japan11641040ReSonutehewastaAbsialesgeneratio68n5(TW11h62)BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.17:Renewablesgeneration(TWh)Renewablesgeneration(TWh)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledgesTableA.12071:0Rene20w21able2s02g2ener2a03t0ion(2T0W50h)20302050World42097964859916915379731929555057NorthAmerica856137414972828652635389261UnitedStates4418679732205551028077683CentralandSouthAmerica75289610181296232014283768Brazil43750859470011027321378Europe954160116203081518034386834EuropeanUnion653108110852177371324074720Africa11620121048615057113453MiddleEast18384521610412332577Eurasia226287277339537380844Russia167221205243380254456AsiaPacific128735683932866920863956828321China78224482681607412664641914836India161351399981414910905660Japan106212225385651412797SoutheastAsia10431034054116307383773IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA287SolarPVgeneration(TWh)BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.18:SolarPVgeneration(TWh)SolarPVgeneration(TWh)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledges2010202120222030205020302050World3210231291540517220639024297NorthAmerica3167203868326711913932UnitedStates3148185829306911263366CentralandSouthAmerica035531604222561255Brazil01730102223119364Europe2319924575314528441852EuropeanUnion2215920262611866891310Africa014161225262451859MiddleEast013171476431411574Eurasia056184425110Russia023616741AsiaPacific6589750333610868368813715China13274292294680124287889India07610548024995343145Japan48695162234171245WSoinuthdeagsteAsniaeration(TWh0)38451266332131293BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.19:Windgeneration(TWh)Windgeneration(TWh)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledgesTable20A10.19:W202i1ndge20n22eratio20n30(TWh20)5020302050620818432World342186521255229118011421NorthAmerica399810543850011072209UnitedStates953834421001191712493516CentralandSouthAmerica31061192526562791105Brazil27282158406165466Europe1545005571304238215183489EuropeanUnion140387420985179011212594Africa2232590302128593MiddleEast0342623242665Eurasia068239242249Russia035126917114AsiaPacific777899122427592727788333ChinaIndia456567621963387620264026JapanSoutheastAsia20777918910712411449491064208783140914552281481207IEA.CCBY4.0.288InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Nucleargeneration(TWh)BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.20:Nucleargeneration(TWh)Nucleargeneration(TWh)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledges2010202120222030205020302050World2756281026823351435334965301NorthAmerica9359168989259349261195UnitedStates8398128048258048251023CentralandSouthAmerica22262331753583Brazil15151524452445Europe1032889750808781894970EuropeanUnion854732607623576703698Africa12121124432972MiddleEast01526458951146Eurasia173225226238306238315Russia170223224236297236297AsiaPacific5827267481281212513222520China7440841864212476611483India264750128337125355Japan2887160207206232289NaSotuutheraastlAgsiaasgeneration0(TWh)0008012BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.21:Naturalgasgeneration(TWh)Naturalgasgeneration(TWh)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledgesTableA.220110:Nat2u02ra1lga2s02g2ener2a03t0ion(2T0W50h)20302050World4847652665006613621060553319NorthAmerica12171933203919168851584366UnitedStates10181633174715385131245169CentralandSouthAmerica17026521124319721771Brazil3687423942205Europe94688884748921740475EuropeanUnion5895465473341042528Africa234366369449638369275MiddleEast5279079191207163612231102Eurasia603653673745878679727Russia521514524575598531535AsiaPacific115115141443156417591579704China92290257349371376133India1076239831758164Japan3323593592169219370SoutheastAsia336330338508768445244IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA289Coalgeneration(TWh)BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.22:Coalgeneration(TWh)Coalgeneration(TWh)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledges2010202120222030205020302050World866910247104288337497869982244NorthAmerica210610439762221211930UnitedStates19949929142061210430CentralandSouthAmerica4167513119111Brazil11241411500Europe106866369128522321159EuropeanUnion755453484883792Africa2592462451886016218MiddleEast0113433Eurasia235267288212198199132Russia166187206117981178981767396446362922000AsiaPacific49587961553646622213397810441270147210291280China326354324953331966619060India6581170527645874563267Japan317322ToSotuathleafsitnAsaialconsumpti1o8n5(EJ)508BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.23:Totalfinalconsumption(EJ)Totalfinalconsumption(EJ)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledgesTableA2.02103:To2ta02l1final20c22onsum203p0tion20(5E0J)20302050World382.7436.2442.4482.0535.8451.0429.0NorthAmerica76.577.179.277.672.673.254.7UnitedStates63.864.966.464.358.160.844.1CentralandSouthAmerica19.220.221.023.729.422.523.8Brazil9.110.010.411.513.711.111.9Europe63.060.657.356.749.953.839.4EuropeanUnion45.943.941.840.132.738.126.1Africa20.725.425.929.742.825.333.3MiddleEast19.323.724.629.439.928.235.9Eurasia23.628.428.529.131.327.926.9Russia19.023.423.422.923.222.119.8AsiaPacific145.3187.7190.9216.2242.8201.2193.2China76.3106.1106.9116.4112.9110.290.5India19.027.429.338.055.733.443.3Japan14.112.012.011.09.310.57.5SoutheastAsia16.119.219.824.733.823.027.0IEA.CCBY4.0.290InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Industryconsumption(EJ)BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.24:Industryconsumption(EJ)Industryconsumption(EJ)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledges2010202120222030205020302050World143.0166.7166.6186.8207.3179.2175.4NorthAmerica17.818.919.120.522.219.618.9UnitedStates14.015.015.216.117.115.414.5CentralandSouthAmerica7.26.86.97.89.47.58.4Brazil3.93.94.04.45.34.34.7Europe19.519.217.518.117.417.315.1EuropeanUnion14.314.112.913.011.612.410.2Africa3.94.24.25.18.45.07.3MiddleEast8.09.610.111.814.211.513.2Eurasia8.49.69.59.710.69.69.7Russia6.88.48.38.28.48.17.8AsiaPacific78.298.599.3113.9125.0108.8102.8China49.562.662.668.063.665.051.4India7.912.513.419.029.817.723.5Japan6.15.35.24.94.44.83.9TrSaounthsepasotArstiaconsumptio6.n2(EJ)8.68.811.115.110.713.4BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.25:Transportconsumption(EJ)Transportconsumption(EJ)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledgesTableA20.1205:Tra20n21sport20c22onsum203p0tion2(05E0J)20302050World101.7112.4116.5127.5139.2121.8106.3NorthAmerica29.629.229.928.223.226.615.8UnitedStates25.025.325.623.918.922.513.3CentralandSouthAmerica6.17.17.48.711.38.38.0Brazil2.93.63.84.24.74.13.9Europe15.615.816.014.911.014.18.0EuropeanUnion11.711.511.710.46.79.95.0Africa3.65.05.16.010.35.88.5MiddleEast4.95.66.07.09.76.77.7Eurasia4.75.15.15.35.75.25.0Russia4.04.14.14.03.63.93.2AsiaPacific22.031.532.138.041.136.231.6China8.314.614.316.413.215.810.7India2.74.34.76.69.26.27.2Japan3.32.72.62.21.72.11.1SoutheastAsia3.75.15.57.18.96.76.5IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA291Buildingsconsumption(EJ)BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.26:Buildingsconsumption(EJ)Buildingsconsumption(EJ)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledges2010202120222030205020302050World116.8131.2132.5138.5158.9122.5122.2NorthAmerica23.723.924.823.321.721.615.6UnitedStates20.520.321.219.717.918.412.8CentralandSouthAmerica4.45.05.15.56.64.95.7Brazil1.41.71.81.92.61.82.3Europe24.322.320.620.518.619.214.0EuropeanUnion17.616.014.814.412.413.69.4Africa12.415.415.717.622.513.616.1MiddleEast5.46.97.19.114.58.513.6Eurasia8.410.610.610.811.510.19.1Russia6.27.97.97.77.87.25.9AsiaPacific38.247.148.551.863.444.548.2China15.723.824.726.431.424.325.0India7.08.38.69.111.86.48.5Japan4.33.73.73.52.93.32.3SouTthoeatstaAlsiahydrogende5.m3and4.(4PJ)4.45.28.34.46.0BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSeStsatatSetcedednPaPoroliiolciciSeietsasStScecedenPnaoarirloicoSiAetasntnSecodeuPnnoacrleicodiAePsnlenSdcoegunensacrSeiocdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.27:Hydrogendemand(PJ)Totalhydrogendemand(PJ)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledgesTableA.22702:1Hydr2o02g2end2e03m0and205(0PJ)20302050World11129114251321916631139153559626668214NorthAmerica1788190621822866222872525972499UnitedStates146615701743231710139712482860CentralandSouthAmerica33335648377693619325261930Brazil43528210917894300851850Europe1029969100211387777446373EuropeanUnion77971474283635491536112276772Africa3493584687112742902544901MiddleEast1386147918592404292340508Eurasia850842881899Russia778774806807AsiaPacific5394551564538184China3278329036233763India963100613212123Japan211230216259SoutheastAsia418447538812Internationalbunkers--438IEA.CCBY4.0.292InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Low-emissionshydrogenbalance(MtH₂equivalent)BTaackbtolceonAten.ts2p8a:geLow-emissionshStyatdedroPgSoltieactinesdbSPScaotelailnctaeiaednrsioPcSAoeclneicn(ieoaMsurinoStcAceHnedn22opaeulreinodqqcgNeuedesitvpsZlaeceedrloengNaeEnerstimotsZ)icseesronioaEnrsimobisys2io0n5s0bSyc2e0n5a0rioScenarLow-emissionshydrogenbalance(MtH₂equivalent)StatedAnnouncedNetZeroPoliciesPledgesEmissionsby20502022203020502030205020302050Low-emissionshydrogenproduction17302524670420Waterelectrolysis05221618951327FossilfuelswithCCUS1288561889Bioenergyandother0000102Transformationofhydrogen05151411640200Topowergeneration-134231751Tohydrogen-basedfuels-0468316142Inoilrefining0274766Tobiofuels0012411Hydrogendemandforend-usesectors03161013030220Low-emissionshydrogen-basedfuels-0336212104Totalfinalconsumption-01347784Powergeneration-02015420Trade-165421458ToTtraadleCasOsha₂reeomfdeimsasnidons(MtCO₂)18%21%18%17%21%14%BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.29:TotalCO2emissions(MtCO2)TotalCO₂emissions(MtCO₂)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledges2010202120222030205020302050WorldTableA.32298:77Tota36l5C89O₂e36m93i0ssion35s125(Mt2C96O96₂)3076912043NorthAmerica277647056315702457028923683UnitedStates54564669469736081982290010CentralandSouthAmerica115311851178120513331044542Brazil411479452448473374172Europe472039903826296118462390346EuropeanUnion3311274426621885882151581Africa1168136413851468199113281171MiddleEast1637205621192333273721511816Eurasia2153233023482193214420661644Russia1688184618561645147015691192192601898214883167885269AsiaPacific144501905112135112611946689799491481China8799121102627325233632875106276342India168524621733442684982204725301836Japan12011057SoutheastAsia11631690Includesindustrialprocessandflaringemissions.IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexATablesforscenarioprojectionsA293ElectricityandheatsectorsCO₂emissions(MtCO₂)BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTTaabbleAA..3300::EElleeccttrriicciittyyaannddhheeaattsseeccttoorrssCCOO₂2emissions(MtCO₂2)ElectricityandheatsectorsCO₂emissions(MtCO₂)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledges2010202120222030205020302050World125111459814822123028217105973004NorthAmerica259618591835991343712-32UnitedStates234616271599813206558-102CentralandSouthAmerica23526222217111112634Brazil4688503730112Europe17321213121060236146567EuropeanUnion118880582730274244-5Africa421464468418329360153MiddleEast550694701719776680486Eurasia103410191041911873853686Russia89283485071062167654674011610AsiaPacific5943908793468490542546431218761China35095967614153312817321250-6India785116612271408998792350Japan50048250126685FiSnouathlecasotAnsisaumptionCO3₂98emis7s0i5ons7(2M6tCO8₂7)91115BacktocontentspageStatedPoliciSetsatSecdenPaorliiociSetsatSecdenPaorliiocieSstaStceednaProiolicSietastSecdePnoarlicoiAesnnScoeunnacreiodAPnlendoguenscSecdePnlaerdiogesScenarioTableA.31:TotalfinalconsumptionCO2emissions(MtCO2)FinalconsumptionCO₂emissions(MtCO₂)HistoricalStatedAnnouncedPoliciesPledgesTableA.31:Totalfi2n01a0lcon20s2u1mpt2i0o2n2CO₂20e30miss2i0o5n0s(M20t30CO₂2)050World1866820191202932104619950188768952NorthAmerica345533433419312821822697436UnitedStates285027832820252915962201245CentralandSouthAmerica8078348619521137858482Brazil342371382396433356172Europe281326282476223613991859281EuropeanUnion2009183917361498749122780Africa5617237438861496835993MiddleEast924110411551329169012511227Eurasia92411741172116311801102901Russia672905900847787810609AsiaPacific8057940393559939899789573653China5027581856645584381150231208India866122413251751228015951144Japan67255854348436842369SoutheastAsia690901930112413631013621Includesindustrialprocessemissions.IEA.CCBY4.0.294InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023AnnexBDesignofthescenariosTheWorldEnergyOutlook-2023(WEO-2023)exploresthreemainscenariosintheanalysisinthechapters.Thesescenariosarenotpredictions–theIEAdoesnothaveasingleviewonthefutureoftheenergysystem.Thescenariosare:TheStatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS)isdesignedtoprovideasenseoftheprevailingdirectionofenergysystemprogression,basedonadetailedreviewofthecurrentpolicylandscape.Itexploreshowenergysystemsevolveundercurrentpoliciesandprivatesectormomentumwithoutadditionalpolicyimplementation.Thescenarioisnotdevelopedwithaparticularoutcomeinmind,butratheraimstoholdamirroruptopolicymakerstounderstandwherecurrenteffortsarelikelytoleadglobalenergysystems.TheSTEPSdoesnottakeforgrantedthatallgovernmenttargetswillbeachieved.Instead,ittakesagranular,sector-by-sectorlookatexistingpoliciesandmeasures,asoflateAugust2023.Newthisyear,theSTEPStakesintoaccountindustryaction,includingmanufacturingcapacityofcleanenergytechnologies,anditsimpactsonmarketuptakebeyondthepoliciesinplaceorannounced.AsnapshotofthemajorpoliciesconsideredintheSTEPSispresentedinTablesB.6toB.11.TheAnnouncedPledgesScenario(APS)assumesthatgovernmentswillmeet,infullandontime,theclimatecommitmentstheyhavemade,includingtheirNationallyDeterminedContributionsandlonger-termnetzeroemissionstargets.AswiththeSTEPS,theAPSisnotdesignedtoachieveaparticularoutcome,butinsteadprovidesabottom-upassessmentofhowcountriesmaydeliveronclimatepledges.Countrieswithoutambitiouslong-termpledgesareassumedtobenefitinthisscenariofromtheacceleratedcostreductionsandwideravailabilityofcleanenergytechnologies.ThelistofadditionalclimateandenergytargetsmetintheAPSispresentedinTablesB.6toB.11.AllnetzeroemissionspledgesconsideredintheAPSareincludedintheIEAClimatePledgesExplorer.1TheNetZeroEmissionsby2050(NZE)Scenariodepictsanarrowbutachievablepathwayfortheglobalenergysectortoreachnetzeroenergy-relatedCO2emissionsby2050bydeployingawideportfolioofcleanenergytechnologiesandwithoutoffsetsfromland-usemeasures.ItrecognisesthatachievingnetzeroenergysectorCO2emissionsby2050dependsonfairandeffectiveglobalco-operation,withadvancedeconomiestakingtheleadandreachingnetzeroemissionsearlierintheNZEScenariothanemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies.Thisscenarioalsoachievesuniversalenergyaccessby2030,consistentwiththeenergy-relatedtargetsoftheUnitedNationsSustainableDevelopmentGoals.TheNZEScenarioisconsistentwithlimitingtheglobaltemperatureriseto1.5°C(withatleasta50%probability)withlimitedovershoot.IEA.CCBY4.0.1TheIEAClimatePledgesExplorerisavailableat:http://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-tools/climate-pledges-explorerAnnexBDesignofthescenarios295B.1PopulationTableB.1⊳PopulationassumptionsbyregionCompoundaveragePopulationUrbanisationannualgrowthrate(million)(shareofpopulation)2022203020502000-222022-302022-5020222030205083%84%89%50552856583%85%89%NorthAmerica0.9%0.6%0.4%33635037282%83%88%52955960188%89%92%UnitedStates0.7%0.5%0.4%21522423176%78%84%69569668275%77%83%C&SAmerica1.0%0.7%0.5%44944642644%48%59%73%75%81%Brazil0.9%0.5%0.2%14251708248265%67%73%26529736475%77%83%Europe0.3%0.0%-0.1%23824325350%55%64%14314013264%71%80%EuropeanUnion0.2%-0.1%-0.2%36%40%53%42954489473492%93%95%Africa2.6%2.3%2.0%14201410130751%56%66%14171515167057%60%68%MiddleEast2.2%1.4%1.1%125119105Eurasia0.4%0.3%0.2%679723787795085209681Russia-0.1%-0.3%-0.3%AsiaPacific1.0%0.6%0.3%China0.5%-0.1%-0.3%India1.3%0.8%0.6%Japan-0.1%-0.6%-0.6%SoutheastAsia1.2%0.8%0.5%World1.2%0.9%0.7%Notes:C&SAmerica=CentralandSouthAmerica.SeeAnnexCforcompositionofregionalgroupings.Sources:UNDESA(2018,2022);WorldBank(2023a);IEAdatabasesandanalysis.PopulationisamajordeterminantofmanyofthetrendsintheOutlook.WeusethemediumvariantoftheUnitedNationsprojectionsasthebasisforpopulationgrowthinallscenarios,butthisisnaturallysubjecttoadegreeofuncertainty.Onaverage,therateofpopulationgrowthisassumedtoslowovertime,buttheglobalpopulationapproaches9.7billionby2050(TableB.1).Aroundthree-fifthsoftheincreaseovertheprojectionperiodto2050isinAfricaandaroundafurtherquarterisintheAsiaPacificregion.Theshareoftheworld’spopulationlivingintownsandcitieshasbeenrisingsteadily,atrendthatisprojectedtocontinueovertheperiodto2050.Inaggregate,thismeansthatvirtuallyallofthe1.7billionincreaseinglobalpopulationovertheperiodisaddedtocitiesandtowns.IEA.CCBY4.0.296InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023B.2CO2pricesTableB.2⊳CO2pricesforelectricity,industryandenergyproductioninselectedregionsbyscenarioUSD(2022,MER)pertonneofCO2203020402050StatedPoliciesScenarioCanada130150155ChileandColombia132129China284353EuropeanUnion120129135Korea426789AnnouncedPledgesScenarioAdvancedeconomieswithnetzeroemissionspledges135175200Emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomieswith40110160netzeroemissionspledges1747Otheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies-205250NetZeroEmissionsby2050Scenario140160200Advancedeconomieswithnetzeroemissionspledges90Emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomieswith85180netzeroemissionspledges253555Selectedemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies15(withoutnetzeroemissionspledges)OtheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesNote:Valuesarerounded.IncludesallOECDcountriesexceptMexico.IncludesChina,India,Indonesia,BrazilandSouthAfrica.IEA.CCBY4.0.Thereare73directcarbonpricinginstrumentsinplacetoday,coveringaround40countriesandover30subnationaljurisdictions.Globalcarbonpricingrevenuesin2022increasedbyover10%from2021levels,toaroundUSD95billion(WorldBank,2023b).ExistingandscheduledCO2pricingschemesarereflectedintheSTEPS,coveringelectricitygeneration,industry,energyproductionsectorsandotherend-usesectors,e.g.aviation,roadtransportandbuildings,whereapplicable.IntheAPS,higherCO2pricesareintroducedacrossallregionswithnetzeroemissionspledges.Noexplicitpricingisassumedinsub-SaharanAfrica(excludingSouthAfrica)andOtherAsiaregions.Instead,theseregionsrelyondirectpolicyinterventionstodrivedecarbonisationintheAPS.IntheNZEScenario,CO2pricescoverallregionsandriserapidlyacrossalladvancedepcleodngoems,ieinscalusdwinegllCashiinnap,rIonmdiian,eInndtoemneesrigai,nBgramzailraknedteScoountohmAifersicwa.itChOn2eptrziceersoaermeilsoswioenrs,BbutneverthelessrisinginotheremergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiessuchasAnnexBDesignofthescenarios297NorthAfrica,MiddleEast,RussiaandSoutheastAsia(excludingIndonesia).CO2pricesarelowerintheremainingdevelopingeconomies,asitisassumedtheypursuemoredirectpoliciestoadaptandtransformtheirenergysystems.AllscenariosconsidertheeffectsofotherpolicymeasuresalongsideCO2pricing,suchascoalphase-outplans,efficiencystandardsandrenewabletargets(TablesB.6-B.11).Thesepoliciesinteractwithcarbonpricing;therefore,CO2pricingisnotthemarginalcostofabatementasitisoftenthecaseinothermodellingapproaches.IEA.CCBY4.0.298InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023B.3FossilfuelresourcesTableB.3⊳Remainingtechnicallyrecoverablefossilfuelresources,2022OilProvenResourcesConventionalTightNGLsEHOBKerogen(billionbarrels)reservescrudeoiloiloilNorthAmerica2151467971000CentralandSouthAmerica220239223557494973Europe30319286Africa1485424754833-MiddleEast12529171230Eurasia9001115685581418AsiaPacific146726455216World514513125316003107317601868112287893722427512061422071NaturalgasProvenResourcesConventionalTightShaleCoalbed(trillioncubicmetres)reservesgasgasgasmethaneNorthAmerica1081CentralandSouthAmerica171475015417Europe918-Africa584285405MiddleEast10110Eurasia19461810-AsiaPacific8395317World691015110253202121492221211018016712913844803421CoalProvenResourcesCokingSteamLignite(billiontonnes)reservescoalcoalNorthAmerica8389111957511519CentralandSouthAmerica25760325Europe1498216432403Africa13734346414-MiddleEast154136296-Eurasia386632AsiaPacific1201517365191897499714284605810World1074208043490133064007Notes:NGLs=naturalgasliquids;EHOB=extra-heavyoilandbitumen.ThebreakdownofcoalresourcesbytypeisanIEAestimate.CoalworldresourcesexcludeAntarctica.Sources:BGR(2021);BP(2022);CEDIGAZ(2022);OGJ(2022);USEIA(2013,2015,2023);USGS(2012a,2012b);IEAdatabasesandanalysis.IEA.CCBY4.0.BAnnexBDesignofthescenarios299TheWorldEnergyOutlooksupplymodellingreliesonestimatesoftheremainingtechnicallyrecoverableresource,ratherthanthe(oftenmorewidelyquoted)numbersforprovenreserves.Resourceestimatesaresubjecttoaconsiderabledegreeofuncertainty,aswellasthedistinctionintheanalysisbetweenconventionalandunconventionalresourcetypes.Overall,theremainingtechnicalrecoverableresourcesoffossilfuelsremainsimilartotheWorldEnergyOutlook-2022.Allfuelsareatalevelcomfortablysufficienttomeettheprojectionsofglobalenergydemandgrowthto2050inallscenarios.RemainingtechnicallyrecoverableresourcesofUStightoil(crudepluscondensate)totalmorethan200billionbarrels.Overall,thegradualdepletionofresources(atapacethatvariesbyscenario)meansthatoperatorshavetodevelopmoredifficultandcomplexreservoirs.Thistendstopushupproductioncostsovertime,althoughthiseffectisoffsetbytheassumedcontinuousadoptionofnew,moreefficientproductiontechnologiesandpractices.Worldcoalresourcesaremadeupofvarioustypesofcoal:around80%issteamandcokingcoalandtheremainderislignite.Coalresourcesaremoreavailableinpartsoftheworldwithoutsubstantialnaturalgasandoilresources,notablyinAsia.IEA.CCBY4.0.300InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023B.4ElectricitygenerationtechnologycostsTableB.4a⊳TechnologycostsinselectedregionsintheStatedPoliciesScenarioCapitalcostsCapacityfactorFuel,CO2,O&MLCOEVALCOE(USD/kW)(%)(USD/MWh)(USD/MWh)(USD/MWh)202220302050202220302050202220302050202220302050202220302050UnitedStatesNuclear500048004500909090303030105105100105105100Coal2100210021003515n.a.302525100210n.a.100205n.a.GasCCGT1000100010005540154540406570120656575101010503025555560SolarPV1120690480212223101010303030354040Windonshore122011601110424344Windoffshore40602520190042464935201512070501258060EuropeanUnionNuclear660051004500707580353535160130110160130110Coal20002000200030n.a.n.a.125150160205n.a.n.a.190n.a.n.a.GasCCGT1000100010002010n.a.170125130230270n.a.205190n.a.SolarPV990620450141414101010654035808590201515605555656560Windonshore175016701610293030Windoffshore342022801740505659151010754535755540China280028002500807570252525707065707065Nuclear8008008005030205060706590115657065CoalGasCCGT560560560302015959510012013014010510090SolarPV720430300131314101010503025656070101010454035505050Windonshore11001040100026272825151010060401056540Windoffshore282018801420323943India280028002800808590303030707065707065Nuclear120012001200657070403530605550605040CoalGasCCGT70070070025404595706012590801207050SolarPV640390270202122555402515454055151010554540605055Windonshore11201060101026283025201513585601359065Windoffshore306020601500333739Notes:O&M=operationandmaintenance;LCOE=levelisedcostofelectricity;VALCOE=value-adjustedLCOE;kW=kilowatt;MWh=megawatt-hour;CCGT=combined-cyclegasturbine;n.a.=notapplicable.Costcomponents,LCOEandVALCOEfiguresarerounded.LowervaluesforVALCOEindicateimprovedcompetitiveness.Sources:IEAanalysis;IRENA(2023).IEA.CCBY4.0.BAnnexBDesignofthescenarios301TableB.4b⊳TechnologycostsinselectedregionsintheAnnouncedPledgesScenarioCapitalcostsCapacityfactorFuel,CO2andO&MLCOE(USD/kW)(%)(USD/MWh)(USD/MWh)202220302050202220302050202220302050202220302050UnitedStates90909030303010510510030n.a.n.a.90150180175n.a.n.a.Nuclear5000480045005025n.a.70909521222310101095135n.a.Coal210021002100424344101010503025424649352015303030GasCCGT1000100010001207045708080353535SolarPV112066046030n.a.n.a.1351752151551201102510n.a.170130140220n.a.n.a.Windonshore122011501080141414220270n.a.293030101010Windoffshore40602440172050565920151565403015105605550EuropeanUnion757070754530502515252525Nuclear660051004500353020558515070706513131410011012570125220Coal20002000200026272810105120130160323943101010503025GasCCGT1000100010002515104540357585901005535SolarPV9906004106570503030302535254065165707065Windonshore1750165015702021229075105608519526283012095140Windoffshore342022001540333739555402515151010554540China2520101358555Nuclear280028002500Coal800800800GasCCGT560560560SolarPV720420290Windonshore11001030980Windoffshore282018201280IndiaNuclear280028002800Coal120012001200GasCCGT700700700SolarPV640380250Windonshore11201050980Windoffshore306019801340Notes:O&M=operationandmaintenance;LCOE=levelisedcostofelectricity;kW=kilowatt;MWh=megawatt-hour;CCGT=combined-cyclegasturbine;n.a.=notapplicable.CostcomponentsandLCOEfiguresarerounded.Sources:IEAanalysis;IRENA(2023).IEA.CCBY4.0.302InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023TableB.4c⊳TechnologycostsinselectedregionsintheNetZeroEmissionsby2050ScenarioCapitalcostsCapacityfactorFuel,CO2andO&MLCOE(USD/kW)(%)(USD/MWh)(USD/MWh)202220302050202220302050202220302050202220302050UnitedStates90908530303010510510530n.a.n.a.90155220185n.a.n.a.Nuclear5000480045005025n.a.708511021222310101095135n.a.Coal210021002100424344101010503025424649352015303025GasCCGT1000100010001206545707565353535SolarPV112064044025n.a.n.a.1401852501601301252510n.a.165125150235n.a.n.a.Windonshore122011401070141414215240n.a.293030101010Windoffshore40602360164050565920151565403015105605550EuropeanUnion85807575453055n.a.n.a.252525Nuclear6600510045004535n.a.7012018065656513131411012514590n.a.n.a.Coal20002000200026272810105120140n.a.323943101010503020GasCCGT1000100010002515104540357585901005535SolarPV99058041065n.a.n.a.3030302530n.a.40105200707065Windonshore175016401550202122807511060n.a.n.a.262830110100n.a.Windoffshore342021401500333739555402015151010554540China2515101357550Nuclear280028002500Coal800800800GasCCGT560560560SolarPV720410280Windonshore11001030960Windoffshore282017601220IndiaNuclear280028002800Coal120012001200GasCCGT700700700SolarPV640360240Windonshore11201040960Windoffshore306018401260Notes:O&M=operationandmaintenance;LCOE=levelisedcostofelectricity;kW=kilowatt;MWh=megawatt-hour;CCGT=combined-cyclegasturbine;n.a.=notapplicable.CostcomponentsandLCOEfiguresarerounded.Sources:IEAanalysis;IRENA(2023).IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexBDesignofthescenariosB303Allcostsareexpressedinyear-2022dollars.Majorcontributorstothelevelisedcostofelectricity(LCOE)include:overnightcapitalcosts;capacityfactorthatdescribestheaverageoutputovertheyearrelativetothemaximumratedcapacity(typicalvaluesprovided);costoffuelinputs;plusoperationandmaintenance.Economiclifetimeassumptionsare25yearsforsolarPV,andonshoreandoffshorewind.Weightedaveragecostofcapital(WACC)assumptionsreflectmarketdataandsurveyinformationprovidedthroughtheCostofCapitalObservatory(IEA,2023),updatedanalysisforutility-scalesolarPVintheWorldEnergyOutlook-2020(IEA,2020),witharangeof4-7%,andforoffshorewindanalysisfromtheOffshoreWindOutlook2019(IEA,2019),witharangeof5-8%.OnshorewindwasassumedtohavethesameWACCasutility-scalesolarPV.AstandardWACCwasassumedfornuclearpower,coal-firedandgas-firedpowerplants(8-9%basedonthestageofeconomicdevelopment).Thevalue-adjustedlevelisedcostofelectricity(VALCOE)incorporatesinformationonbothcostsandthevalueprovidedtothesystem.BasedontheLCOE,estimatesofenergy,capacityandflexibilityvalueareincorporatedtoprovideamorecompletemetricofcompetitivenessforpowergenerationtechnologies.Fuel,CO2andoperationandmaintenancecostsreflecttheaverageoverthetenyearsfollowingtheindicateddateintheprojections(andthereforevarybyscenarioin2022).SolarPVandwindcostsdonotincludethecostofenergystoragetechnologies,suchasutility-scalebatteries.Thecapitalcostsfornuclearpowerrepresentthe“nth-of-a-kind”costsfornewreactordesigns,withsubstantialcostreductionsfromthefirst-of-a-kindprojects.IEA.CCBY4.0.304InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023B.5OtherkeytechnologycostsTableB.5⊳CapitalcostsforselectedtechnologiesbyscenarioStatedPoliciesAnnouncedPledgesNetZeroEmissions20302050by205020222030205020302050Iron-basedsteelproduction340-500340-450360-490380-630490-690440-650590-740(USD/tpa)n.a590-770570-730590-780540-700600-760570-720ConventionalInnovativeVehicles(USD/vehicle)16800153001540015200153001510015200Hybridcars166001470016100141001560013700Batteryelectriccars20500Batteriesandhydrogen1070-1640630-980530-740540-710360-510420-610330-470Hydrogenelectrolysers9565455030(USD/kW)5535130Fuelcells(USD/kW)315185140175Utility-scalestationary180135batteries(USD/kWh)Notes:kW=kilowatt;tpa=tonneperannum;kWh=kilowatt-hour;n.a.=notapplicable.AllvaluesareinUSD(2022).Sources:IEAanalysis;Jameset.al.(2018);Thompson,etal.(2018);FinancialTimes(2020);BNEF(2022);Coleetal.(2021);Tsiropoulosetal.(2018);JATO(2021).IEA.CCBY4.0.Allcostsrepresentfullyinstalled/deliveredtechnologies,notsolelythemodulecost,unlessotherwisenoted.Installed/deliveredcostsincludeengineering,procurementandconstructioncoststoinstallthemodule.Iron-basedsteelproductioncostsdisplayarangeconsideringtechnologyandregionaldifferencesanddifferentiatebetweenconventionalandinnovativeproductionroutes.Conventionalroutesareblastfurnace-basicoxygenfurnace(BF-BOF)anddirectreducediron-electricarcfurnace(DRI-EAF).Theinnovativeroutesareinnovativesmeltingreductionwithcarboncapture,utilisationandstorage(CCUS),DRI-EAFwithCCUS,100%electrolytichydrogen-basedDRI-EAFandironoreelectrolysis.Vehiclecostsreflectproductioncosts,notretailprices,tobetterreflectthecostdeclinesintotalcostofmanufacturing,whichmoveindependentlyoffinalmarketpricesforelectricvehiclestocustomers.Electrolysercostsreflectaweightedaverageamongdifferentelectrolysistechnologies.ThelowervalueforhydrogenelectrolysersreferstoChinaandtheupperonetotherestoftheworld.Fuelcellcostsarebasedonstackmanufacturingcostsonly,notinstalled/deliveredcosts.Thecostsprovidedareforautomotivefuelcellstacksforlight-dutyvehicles.Utility-scalestationarybatterycostsreflecttheaverageinstalledcostsofallbatteryBsystemsratedtoprovidemaximumpoweroutputforafour-hourperiod.AnnexBDesignofthescenarios305B.6PoliciesThepolicyactionsassumedtobetakenbygovernmentsarekeyvariablesinthisWorldEnergyOutlook(WEO).AnoverviewofthepoliciesandmeasuresthatareconsideredinthevariousscenariosisincludedinTablesB.6toB.11.Thetablesdonotincludeallpoliciesandmeasures,butratherhighlightthepoliciesmostprominentinshapingglobalenergydemandtoday,whilebeingderivedfromanexhaustiveexaminationofannouncementsandplansincountriesaroundtheworld.Thetablesbeginwithbroadcross-cuttingpolicyframeworks,followedbymoredetailedpoliciesbysector:power,industry,buildingsandtransport.ThetableshighlightpoliciesandtargetsforboththeStatedPoliciesScenario(STEPS)andtheAnnouncedPledgesScenario(APS).FortheSTEPS,thetableslistbothnewpoliciesenacted,implementedorrevisedsincethepublicationoftheWEO-2022,aswellassignificantestablishedlong-termpoliciesthathaveamajorinfluenceontheoutcomesintheSTEPS.Itdoesnottakeforgrantedthatallgovernmenttargetswillbereached.TargetsthatareachievedorsurpassedintheSTEPSarelisted,indicatingthemostrecentIEAassessmentthatconcreteimplementationplansareabletodeliveronthetargets.FortheAPS,targetsnotrealisedintheSTEPSandannouncedpoliciestoachievethesetargetsarelisted.Itindicatesadditionalpolicyeffortstorealisethem.TheAPSassumesallpoliciesincludedintheSTEPStoremaininforce.Someregionalpolicieshavebeenincludedinthetablesiftheyplayasignificantroleinshapingtheenergylandscapeataglobalscale,e.g.regionalcarbonmarkets,efficiencystandardsinverylargeprovincesorstates.ThisWorldEnergyOutlook,forthefirsttime,includesvariousindustry-ledtargetsforenergyandclimate,presentedinTableB.11.Amorecomprehensivelistofenergy-relatedpoliciesbycountrycanbeviewedontheIEAPoliciesandMeasuresDatabaseat:http://www.iea.org/policies.IEA.CCBY4.0.306InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023TableB.6⊳Cross-cuttingpolicyassumptionsforselectedregions/countriesbyscenarioRegion/ScenarioAssumptionscountrySTEPS•Energyprovisionsin:InflationReductionAct(2022);ConsolidatedAppropriationsActUnitedStates(2021);andInfrastructureInvestmentandJobsAct(2021).•DefenceProductionActdeploymentsupportingdomesticproductionofheatpumps,buildinginsulationequipment,solarpanelcomponents,transformersandbatteries.•USMethaneEmissionsReductionActionPlan.APS•UpdatedNDCaimingtoreduceGHGemissionsby50-52%by2030(from2005levels)andnationaltargettoreachnetzeroGHGemissionsby2050.•2021USMethaneEmissionsReductionActionPlan.CommitmenttotheGlobalMethanePledge.CanadaSTEPS•Energyandemissionsreduction-relatedprovisionsinthe2020HealthyEnvironmentandaHealthyEconomyPlan;extendedInvestinginCanadaInfrastructureProgramme;andEmissionsReductionFund.•HydrogenStrategyandStrategicInnovationFund.•RegulationRespectingReductionintheReleaseofMethaneandCertainVolatileOrganicCompounds.APS•CommitmenttoreachnetzeroGHGemissionstargetby2050.•CommitmenttotheGlobalMethanePledge,andtoreducemethaneemissionsfromtheoilandgassectorby40-45%by2025,andfurtherby75%by2030relativeto2012.MeasuresintheHealthyEnvironmentandHealthyEconomyactionplan.LatinAmericaSTEPS•Colombia:EnergyprovisionsintheTenMilestonesin2021PlanandtheNationalandtheStrategyforMitigationofShort-LivedClimatePollutants.Caribbean•Chile:EnergyEfficiencyLaw(2021),energyintensityreductionbyatleast10%by2030comparedto2019.•Brazil:NationalMethaneemissionsreductionprogramme.APS•16pledgesoutof33countriestoreachnetzeroemissionsby2050orbefore,includingBrazil,Chile,CostaRicaandColombia.•UpdatedNDCsfromUruguay(0.9MtCO2by2030).•Colombia:MainprovisionsoftheannouncedJustEnergyTransitionroadmap.•NinecountriescommittingtotheGlobalMethanePledge,includingArgentinaandMexico.EuropeanUnionSTEPS•EnergyspendingprovisionsintheEuropeanGreenDealandnationalrecoveryplanselaboratedwithintheframeworkoftheEURecoveryandResilienceFacility.APS•FullimplementationofthedecarbonisationtargetsintheFitfor55package.•Netzeroemissionstargetby2050embeddedinthe2021EuropeanClimateLaw.•EUmembercountry-leveltargetsforcarbonorclimateneutralitybefore2050:Finlandby2035;Austriaby2040;Germany,PortugalandSwedenby2045.•GreenDealIndustrialPlantargetsenhancingthecompetitivenessofEUnetzeroindustry.•TargetsintheEUHydrogenStrategyforaClimateNeutralEurope.•PartialimplementationofthetargetssetintheREPowerEUPlan,eliminatetheimportofRussiannaturalgassupplytotheEuropeanUnionwellbefore2030.•19EUmemberstatescommitmenttotheGlobalMethanePledge.IEA.CCBY4.0.BAnnexBDesignofthescenarios307TableB.6⊳Cross-cuttingpolicyassumptionsforselectedregions/countriesbyscenario(continued)Region/ScenarioAssumptionscountryOtherEuropeSTEPS•UnitedKingdom:TenPointPlanforaGreenIndustrialRevolutionandprovisionsofAPSthe2021NorthSeaTransitionDeal.AustraliaandNewZealandSTEPS•Norway:2021GreenConversionPackage.APSChina•UnitedKingdom:Commitmenttoreachnetzeroemissionsby2050.NetZeroSTEPSStrategy.BuildBackGreenerPlan.EnergySecurityBilltoprovidepublicsupportfordomesticmanufacturing.•Climateneutralitytargetsby2040(Iceland),and2050(SwitzerlandandNorway).•Türkiye:UpdatedNDCpledgeforapeakinemissionsby2038.Pledgetoreachnetzeroemissionsby2053.•Australia:Spendingandpolicymeasuresfromthe2020ClimateSolutionsPackage;PoweringAustraliaPlan;andLong-TermEmissionsReductionPlan.•Australia:Fullimplementationofthe2022ClimateChangeBillemissionstarget,includingnetzeroemissionsby2050,and43%emissionsreductionby2030relativeto2005.•NewZealand:NetzeroemissionstargetforallGHGexceptbiogenicmethaneby2050.Reductionby50%relativeto2005levelsintheupdatedNDC.CommitmenttotheGlobalMethanePledge.•MadeinChina2025transitionfromheavyindustrytohighervalue-addedmanufacturing.•14thFive-YearPlan:oReduceCO2intensityoftheeconomyby18%from2021to2025.oReduceenergyintensityoftheeconomyby13.5%from2021to2025.o20%non-fossilshareoftheenergymixby2025,25%by2030.•UpdatedNDCandActionPlanforCO2topeakbefore2030:oAimtopeakCO2emissionsbefore2030.oLowerCO2emissionsperunitofGDPbyover65%from2005levelsby2030.IndiaAPS•Carbonneutralitytargetby2060.SoutheastAsiaSTEPS•Energy-relatedelementsoftheProductionLinkedIncentivesprogramme.APS•Enhancedenforcementofenergyefficiencypolicyunderthe2022amendmentstoSTEPSAPStheEnergyConservationAct.•NationalGreenHydrogenMission.IEA.CCBY4.0.•UpdatedNDCtoreducenationalemissionsintensityby45%by2030from2005levels.•Commitmenttoreachnetzeroemissionsby2070.•Indonesia:23%shareofrenewableenergyinprimaryenergysupplyby2025and31%by2050.•Singapore:GreenPlan2030.•Indonesia:Netzeroemissionsby2060orbefore.•BruneiDarussalam,Malaysia,Singapore,VietNam:netzeroemissionstargetsby2050.•Thailand:Climateneutralityby2065.•JustEnergyTransitionPartnershipsinIndonesiaandVietNam.•Indonesia,Malaysia,PhilippinesandVietNam:CommitmenttotheGlobalMethanePledge.308InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023TableB.6⊳Cross-cuttingpolicyassumptionsforselectedregions/countriesbyscenario(continued)Region/ScenarioAssumptionscountryJapanSTEPS•2023GreenTransformation(GX)basicpolicy,promotingrenewableenergy,offshoreAPSwindcostreductionRD&Dprogrammes,hydrogensupplychainsandacceleratedKoreaSTEPSnuclearpolicies.APSMiddleEastAPS•2023BasicHydrogenStrategytoacceleratepublicandprivateinvestmentinthehydrogensupplychain.EurasiaAPS•Climateneutralitytargetby2050.•UpdatedNDC:ReduceGHGemissionsby46%by2030from2013levels.•CommitmenttotheGlobalMethanePledge.•2023newbudgetforenergytechnologydevelopment.•KoreanNewDealprovisionsoncleanenergytechnologies.•10thBasicPlanforLong-termElectricitySupplyandDemand.•CarbonNeutralityandGreenGrowthActforClimateChangecommittingtocarbonneutralityby2050.•FullimplementationoftheFirstNationalBasicPlanforCarbonNeutralityandGreenGrowth.•Netzeroemissionstargetsby2050inUnitedArabEmiratesandOman.SaudiArabia,BahrainandKuwaitaimingfor2060.•UnitedArabEmirates:Commitmenttoreduceemissionsby19%by2030from2019levels.•IraqZeroRoutineFlaringby2030initiative.•EgyptandOman:CommitmenttotheGlobalMethanePledge.•AllNDCsandnetzeroemissionstargets,includingKazakhstanin2060andtheRussianFederationnetzeroemissionspledgewithastrongrelianceonsinksfromland-use,land-usechangeandforestry.•KazakhstanNationalMethaneEmissionsInventoryandReductionProgramme.Note:STEPS=StatedPoliciesScenario;APS=AnnouncedPledgesScenario;NDC=NationallyDeterminedContribution(ParisAgreement);CCUS=carboncapture,utilisationandstorage;GHG=greenhousegases;GW=gigawatt;Gt=gigatonnes;Mt=megatonnes;RD&D=researchdevelopmentanddemonstration.IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexBDesignofthescenariosB309TableB.7⊳Electricitysectorpoliciesandmeasuresasmodelledbyscenarioforselectedregions/countriesRegion/ScenarioAssumptionscountryUnitedSTEPS•InflationReductionAct(2022)grantsandtaxcreditsforrenewables,nuclearpowerandStatesCCUS.APSCanadaSTEPS•100%carbon-freeelectricityorenergytargetsby2050inupto21statesplusPuertoRicoEuropeanAPSandWashingtonDC.UnionSTEPS•30GWoffshorewindcapacityby2030.OtherAPS•22updatedrenewableportfoliostandardpoliciesin2022/23(includingConnecticut,EuropeAPSAfricaSTEPSHawaii,RhodeIsland,Minnesota).APSChinaSTEPS•G7commitment:Achievepredominantlydecarbonisedelectricitysectorby2035.IndiaAPS•Reachnearly90%non-emittingrenewablesgenerationby2030.JapanSTEPS•Phaseoutconventionalcoal-firedplantsby2030.STEPSAPS•G7commitment:Achievepredominantlydecarbonisedelectricitysectorby2035.IEA.CCBY4.0.•16memberstateshavecoalphase-outcommitments.Spainaimstophaseoutcoalby2025,fiveyearsearlierthanitsformerannouncement.NineEUmemberstatesarealreadycoalfree.•Updateddevelopmentplansandtargetsforoffshorewindby2030,notablyinGermany(30GW)andtheNetherlands(21GW).•Highertargetsforrenewables(42.5%renewablesshareofgrossfinalconsumptionby2030)withintheFitfor55package.•G7commitment:Achievepredominantlydecarbonisedelectricitysectorby2035.•UnitedKingdom:EnergySecurityPlansetstargetstoexpandoffshorewind,solarPVandnuclearpower.•G7commitment:Achievepredominantlydecarbonisedelectricitysectorby2035.•Partialimplementationofnationalelectrificationstrategies.•SouthAfrica:Increasedrenewablescapacityandreducedcoal-firedcapacityunderthe2019IntegratedResourcePlan.•Kenya:100%renewableelectricityby2030.•Senegal:32%renewablegrid-connectedinstalledcapacityby2030.•Fullimplementationofnationalelectrificationtargets.•14thFive-yearPlanforRenewablestargetsfor3300TWhofrenewablesby2025,atwofoldincreaseinsolarandwindgeneration,andforover50%ofincrementalelectricityconsumptiontobemetbyrenewables.•Atleast1200GWofinstalledsolarandwindcapacityby2030.•Overallcoalusetodeclineinthe15thFive-YearPlanperiod(2025-2030).•UpdatedNationallyDeterminedContribution:50%cumulativeelectricpowerinstalledcapacityfromnon-fossilfuel-basedenergyresourcesby2030.•Reach500GWofnon-fossilcapacityby2030.•Achieveelectricitygenerationoutlookby2030inthe6thStrategicEnergyPlan.•Restartnuclearpowerplantsalignedwiththe6thStrategicEnergyPlanandtheGreenTransformation(GX)policyinitiative.•Acceleratednuclearexpansion,includingsmallmodularreactors,underdiscussionintheGreenTransformation(GX)ImplementationCouncil.•GreenGrowthStrategy:30-45GWofoffshorewindcapacityin2040.•6thStrategicEnergyPlan,withadditionalpoliciestosupportrenewablesinpowergenerationtoreach2030targets.•G7commitment:Achievepredominantlydecarbonisedelectricitysectorsby2035.310InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023TableB.7⊳Electricitysectorpoliciesandmeasuresasmodelledbyscenarioforselectedregions/countries(continued)Region/ScenarioAssumptionscountryLatinSTEPS•Argentina:NationalEnergyTransitionPlanto2030aimsatleast50%ofrenewableAmericaelectricity,ofwhich1GWisdistributedpowerby2030.andtheAPSCaribbeanSTEPS•Brazil:Atleast23%renewables(excludinghydropower)inthepowersupplyby2030.•Chile:Phaseoutunabatedcoaluseby2040.Australia•24outof33countrieshavetargetstoexpandinstalledcapacityofrenewables.andNewZealand•Colombia:NewNationalEnergyPlan,targettoreach100%renewableelectricityby2050.Korea•CostaRica:GenerationExpansionPlan2022-2040targetfor1775MWofsolarandwindSoutheastcapacity.Asia•Australia:82%renewableelectricitygenerationby2030.STEPS•Increasebothnuclearandrenewablesinelectricitygenerationtoabout35%,anddecreaseAPScoal-firedpowerby2036underthe10thBasicPlanforLong-termElectricitySupplyandSTEPSDemand.APS•Powersectorreductiontargetto45.9%by2030from2018levelsinthe2023updateoftheNationalBasicPlansforCarbonNeutralityandGreenGrowth.•VietNam:PowerDevelopmentPlan8targetsfor2030include:solarcapacitytoincreaseby4GW;onshorewindtoreach22GW;offshorewindtoreach6GW;hydropowertoreach29GW;naturalgastoreach38GW;andcoal-firedcapacitytopeakat30GW.•Cambodia:PowerDevelopmentPlan2022-2040targets3.1GWofsolarcapacityand3GWofhydropowerby2040.•Indonesia:Renewableenergyaccountsforhalf(21GW)oftotalpowercapacityadditionsundertheNationalElectricitySupplyBusinessPlan2019-2028.•Indonesiaadoptedregulationsforearlyretirementofcoal-firedpowerplantsandamoratoriumonnewcoalplantsafter2030.Note:STEPS=StatedPoliciesScenario;APS=AnnouncedPledgesScenario.TWh=terawatt-hour;GW=gigawatt;MW=megawatt.IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexBDesignofthescenariosB311TableB.8⊳Industrysectorpoliciesandmeasuresasmodelledbyscenarioforselectedregions/countriesRegion/ScenarioAssumptionscountryAllregionsAPS•UNResolutiontoendplasticpollutionwithabanonsingle-useplastics.UnitedStatesSTEPS•InflationReductionAct(2022):CleanmanufacturingtaxcreditsforCCUS.CanadaAPS•CarbonUtilizationProcurementGrants:USD100millionavailabletosupportstates,LatinAmericaSTEPSandtheSTEPSlocalgovernmentsandpublicutilitiesforpurchasingprocurementsofproductsCaribbeanderivedfromcapturedCO2emissions.APSEuropeanSTEPS•DepartmentofEnergyIndustrialDecarbonizationRoadmap:80%emissionsreductionUnioncomparedto2015fromenergyefficiency,CCUSandswitchingtolow-emissionsfuels.APSOtherEuropeSTEPS•FederalBuyCleanInitiative:Publicprocurementoflow-carbonconstructionmaterials.APSAustraliaandSTEPS•Cleanindustrypackagesandprovisionstopromotecleanindustry,aspartofBuildingNewZealandCanada'sCleanIndustrialAdvantage.China•Brazil:Energyefficiencyguaranteefund.India•Argentina:Industry4.0developmentplantopromoteefficiencyandhigh-techJapanindustries.Korea•Colombia:25%taxbreakonenergyefficiencyinvestments.•Argentina,BrazilandChile:ProductEfficiencyCalltoActioninitiativeaimstodoubletheefficiencyoflighting,coolingandmotorsby2030.•EmissionsTradingSystemupdate:2.2%annualreductionsofemissionsallowances.•InnovationFundsupportforrenewables,energy-intensiveindustries,storageandCCUS.•Sweden:Governmentcreditguaranteesforgreeninvestment.•France2030:EUR5.6billionforheavyindustrydecarbonisation.•NetZeroIndustryAct:Targettoreach40%ofnearzeroemissionsmaterialproductioncapacityincapacityadditionsintheEuropeanUnionby2030.•UnitedKingdom:IndustrialDecarbonisationChallenge.Pilotfundingforlow-emissionsindustrialclusters,andIndustrialEnergyTransformationFundfundingforenergyefficiency.UKemissionstradingsystem.•UnitedKingdom:IndustrialDecarbonisationStrategyandNetZeroStrategy,includingatargettocaptureandstore20-30MtCO2peryearby2030.•Australia:NationalHydrogenStrategytodevelopcleanhydrogen.STEPS•MadeinChina2025targetsforindustrialenergyintensity.APS•Reducecomprehensiveenergyconsumptionpertonneofsteelby2%by2025.STEPS•Expansionoftheemissionstradingsystemcoveragetoindustry.•MadeinChina2025:RaisingdomesticcontentofelectronicandtransportationSTEPSAPSindustriescorecomponentsandmaterialsto70%by2025.STEPS•Perform,AchieveandTradeSchemetotradeenergysavingcredits.•MakeinIndiaprogramme.Constructionof11industrialcorridors.•ProductionLinkedIncentivesprovidesubsidiesrelatedtonewmanufacturingcapacityforsolarPVandmodernbatteries.•GreenInnovationFundprovidesR&Dfundingforinnovativetechnology.•TechnologyRoadmapforTransitionFinanceinthecement,pulpandpaperbranches.•KoreanNewDealgovernmentinvestmentinindustrialenergyefficiencyby2025.IEA.CCBY4.0.Note:STEPS=StatedPoliciesScenario;APS=AnnouncedPledgesScenario;CCUS=carboncapture,utilisationandstorage;R&D=researchanddevelopment;UN=UnitedNations.312InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023TableB.9⊳Buildingssectorpoliciesandmeasuresasmodelledbyscenarioforselectedregions/countriesRegion/ScenarioAssumptionscountryUnitedSTEPS•InflationReductionAct(2022):TaxrebatesforheatpumpsandenergyefficiencyStatesupgradesinresidentialandcommercialbuildings.•2023updatetominimumenergyperformancestandards(MEPS)forcentralairconditionersandheatpumps.APS•Stateandlocalimplementationofenergysmartandzeroenergybuildingcodes.•FederalBuildingPerformanceStandard:Achievenetzeroemissionsinallfederalbuildingsby2045withinterimtargetsforelectrificationanddecarbonisation.CanadaSTEPS•Large-scaleenergy-efficientretrofitsaspartoftheCanadaInfrastructureBankgrowthplan.GreenerHomesGrantandinterest-freeloansfordeephomeretrofits.•UpdatedNationalEnergyCodeofCanadaforBuildings.•OiltoHeatPumpAffordabilityProgramme.•Updatedapplianceefficiencystandards.APS•Allnewbuildingsmeetzero-carbon-readystandardsby2030.LatinSTEPS•Argentina:StrengthenedbuildingenergycodesandmandatoryefficiencylabellingforAmericanewsocialhousing.andtheCaribbean•Colombia:Supportforefficientlighting,efficientrefrigeratorsandsubstitutionoffirewoodusewithLPGorelectriccookingstoves.•MEPSformajorresidentialappliancesandequipment,includingin:Argentina,Brazil,Chile,Colombia,CostaRica,Ecuador,MexicoandPeru.APS•Chile:Energy2050Strategy:Allhouseholdstohaveaccesstolow-emissionssourcesforheatingandcookingby2040;allnewbuildingstobenetzeroenergyuseby2050.•Allnationalcleancookingtargetsaremet.ThreecountriesarealreadyincompliancewiththeSDG7,whichaimstoensureaccesstoaffordable,reliable,sustainableandmodernenergyforallby2030.EuropeanSTEPS•Country-levelgovernmentincentivesandinvestmentinenergyefficiencyinbuildingsUnionandapplianceupgrades,withintheframeworkoftheEURecoveryandResilienceFacility.•Country-levelbuildingcodeupgrades.•Nationalandsubnationalbansandpoliciestolimittheinstallationofcertainfossilfuelboilersinbuildings.APS•EnergyPerformanceofBuildingsDirective:Objectivetoachieveahighlyenergy-efficientanddecarbonisedbuildingstockby2050.Allnewbuildingstobenetzeroemissionsby2028.Retrofitsrequiredforexistingbuildingswithlowestenergyperformance.Fossilfuelheatingsystemsbannedinneworrenovatedbuildings.•RenovationWave:Objectivetodoubletherateofbuildingenergyretrofitsby2030.OtherSTEPS•Norway:Banonfossilfuelheatinginstallations,financialincentivesforheatpumps,Europeminimumefficiencystandardsforheating.•Türkiye:Minimumefficiencyandrenewableconsumptionstandardsforlargebuildings.•UnitedKingdom:Low-CarbonHeatSupportandHeatNetworksInvestmentProject;2023SocialHousingDecarbonisationFund;HomeUpgradeGrantallocations;andfinancialincentivestopurchasecleanhouseholdtechnologies.APS•Switzerland:Annualrenovationratetargetof3%ofthebuildingstockby2035.IEA.CCBY4.0.•NationalandsubnationalbansandpoliciestolimittheinstallationofcertainfossilfuelBboilersinbuildings.AnnexBDesignofthescenarios313TableB.9⊳Buildingssectorpoliciesandmeasuresasmodelledbyscenarioforselectedregions/countries(continued)Region/ScenarioAssumptionscountrySTEPSAfricaAPS•SouthernAfricanDevelopmentCommunity:lightingstandards.STEPS•MEPSformajorresidentialappliancesandequipment,includinginAlgeria,Benin,Egypt,AustraliaandNewSTEPSGhana,Kenya,Morocco,Nigeria,Rwanda,SouthAfricaandTunisia.ZealandAPSChina•Allnationalcleancookingtargetsmet.EightcountriesarealreadyincompliancewiththeSTEPSSDG7.IndiaAPS•Australia:Fundingforenergyefficiencymeasures,includingenergyratinglabelsandstateJapanSTEPSfundingforbuildingsretrofits.EnergyefficiencystandardsfornewhomesupgradedinKoreaAPS2023.STEPSSoutheastAPS•NewZealand:Replacementofallcoal-firedboilersinschoolswithelectricorrenewableAsiaSTEPSbiomassalternativesby2025.•Standardsetformaximumenergyconsumptionpersquaremetreinbuildings.•GreenandHigh-EfficiencyCoolingActionPlan.•MEPSandenergyefficiencylabellingforroomairconditioners.•14thFive-YearPlanrelatedtoenergyconservationinbuildings:TargettoreachsolarPVcapacityof50GWinnewbuildingsby2025.Geothermalenergyfor100millionsquaremetresofbuildingsfloorspace.•Carbonneutrality/peakingblueprint:Retrofitpublicbuildingsinkeycitiessothattheyare20%moreenergyefficientby2030.Increaseduseoflow-carbonmaterialsandre-useofconstructionwaste.•EnergyConservationandSustainableBuildingCodeaspartoftheEnergyConservationBill(amendment),comprisingnormsorenergyefficiencyandconservation,minimumuseofrenewableenergyandothergreenbuildingrequirements.•CoolingActionPlan.Standardsandlabellingforcommercialairconditioners,freezersandlightbulbs.•Energyefficiencylabellingforresidentialbuildings.•SmartMeterNationalProgrammetofacilitatedemand-sidereductions.•AC@24Campaignincentivisingbehaviouralchangetoreducecoolingenergydemand.•NationalBudget2021:Allocationtodecarboniseandpromoteresilienceinbuildings.•Subsidiesforhighlyefficientheatpumps.2016BuildingsEnergyEfficiencyAct:Standards.•Newresidentialandservicesbuildingscollectivelymeetthenetzeroenergyhomeornetzeroenergybuildingsstandardsby2030.•Rebateforpurchaseofappliancesentitledtoenergyefficiencygrade1.•KoreanNewDeal:Increasedfundingtoimprovetheefficiencyofschools,publichousing,andrecreationalandhealthcarefacilities.•GreenBuildingConstructionSupportActprovidesadministrativeandfinancialsupporttopromotethecreationofgreenbuildings.•Allnewbuildingsmeetzero-carbon-readystandardsstartingin2030.•Malaysia:MEPSandefficiencylabellingforwashingmachines,refrigeratorsandairconditioners.•Philippines:Minimumrequirementsforenergyefficiencyofnewandretrofittedbuildings.•Singapore:Buildingcodesfornewbuildingsandtherefurbishmentofexistingbuildings.•VietNam:MEPSandefficiencylabellingforappliancesandlightinginbuildings.IEA.CCBY4.0.Note:STEPS=StatedPoliciesScenario;APS=AnnouncedPledgesScenario;GW=gigawatt;LPG=liquefiedpetroleumgas;MEPS=minimumenergyperformancestandards;SDG=SustainableDevelopmentGoals.314InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023TableB.10⊳Transportsectorpoliciesandmeasuresasmodelledbyscenarioforselectedregions/countriesRegion/ScenarioAssumptionscountryAllregionsAPS•ZeroEmissionsVehiclesDeclaration:Signedby41governmentsdeclaresthatallsalesUnitedStatesSTEPSofnewcarsandvansaretobezeroemissionsgloballyby2040,andbynolaterthan2035inleadingmarkets.CanadaAPSLatinAmericaAPS•Heavy-dutyvehicles:GlobalMoUsignedby22countriesthattargets100%ofnewandtheSTEPSheavy-dutytruckandbussalestobezeroemissionsby2040.CaribbeanAPS•InflationReductionAct(2022):ProvidesfortaxcreditsforelectriccarpurchasesandinvestmentsinEVcharginginfrastructureto2032.Taxcreditsforbiofuelsincludingsustainableaviationfuel.•Targetof50%ofallnewpassengercarsalestobezeroemissionsvehiclesby2030.•Fueleconomystandardstoimprove8%peryearforpassengercarsandlighttrucksformodelyears2024-2025andbaselinerequirementof10%formodelyear2026relativeto2021levels.GHGemissionsstandardsformodelyears2023-2026thatrequire5-10%emissionsreductionsperyear.•NationalElectricVehicleInfrastructureFormulaProgramme:FundingforconstructionofEVcharginginfrastructure.•California:AdvancedCleanCarsIIregulationaimstoachieve100%zeroemissionspassengercarsandlighttrucksalesby2035.Inaddition,AdvancedCleantrucksandfleetsregulationsrequireanincreaseinsalesofzeroemissionsmedium-dutyandheavy-dutytrucks.Otherstateshaveannouncedsimilaractions.•Announcedmulti-pollutantemissionsstandardsforpassengercarsandlight-dutyvehicles.ProposedPhase3ofheavy-dutyvehiclesemissionsstandards.•SustainableAviationFuelGrandChallengetoscaleuptheproductionofatleast3billiongallonsperyearby2030,andsufficientsustainableaviationfueltomeet100%ofdomesticaviationdemandby2050.•100%ofmedium-dutyandheavy-dutytrucksalestobezeroemissionsvehiclesby2040.•EmissionsReductionPlan:Targettoachieve100%zeroemissionslight-dutyvehiclesinnewvehiclesalesby2035.•100%ofnewmedium-dutyandheavy-dutytrucksalestobezeroemissionsvehiclesby2040.•Targetfor10%sustainableaviationfueluseby2030.•Brazil:Biodieselblendingmandatetoincreaseto15%by2026.•Argentina:35%ofthevehiclessalesaretobeelectricorhybridsby2030.•Colombia:600000EVsontheroadby2030(excludingtwo/three-wheelers).•Chile:Alllight-dutyvehicleandurbanbussalesaretobezeroemissionsby2035andmedium-dutyandheavy-dutytrucksalesby2040.•CostaRica:Targetof100%ofnewlight-dutyvehiclessalestobezeroemissionsvehiclesfrom2050.•Mexico:Allsalesofnewcarsandvanstobezeroemissionsby2040.IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexBDesignofthescenariosB315TableB.10⊳Transportsectorpoliciesandmeasuresasmodelledbyscenarioforselectedregions/countries(continued)Region/ScenarioAssumptionscountryEuropeanSTEPS•100%CO2emissionsreductionforbothnewcarsandvansfrom2035,emissionsUnionstandardsforheavy-dutyvehiclesandFuelEUmaritimeinitiative.•AlternativeFuelsInfrastructureRegulationtoaccelerateEVrecharginginfrastructuredeployment.•RenewableEnergyDirectiveIItosupplyaminimumof14%oftheenergyconsumedinroadandrailtransportfromrenewableenergyby2030.APS•Emissionsperkmfromnewheavy-dutyvehiclestodecreaseby90%by2040,relativetothereferenceperiod(mid-2019–mid-2020).•RevisedCleanVehiclesDirectiveincludingminimumrequirementsforaggregatepublicprocurementforzeroemissionsurbanbuses.•ReFuelEUAviationsetsa70%blendingmandateofsustainableaviationfuelsby2050,withasub-obligationforsyntheticfuels.•FuelEUMaritimeinitiativetargetsthereductionofaverageGHGintensityofenergyusedon-boardbyshipsupto75%by2050relativeto2020levels.OtherEuropeSTEPS•UnitedKingdom:10%ethanolblendmandateby2032.•Switzerland:100%ofnewlight-dutyvehiclesalestobezeroemissionsby2040.APS•Türkiye:100%ofmedium-dutyandheavy-dutytrucknewsalestobezeroemissionsvehiclesby2040.•Norway:Targetfor30%sustainableaviationfueltargetby2030.AustraliaandAPS•Australia:NationalElectricVehicleStrategyincludesdetailsofstate-leveltargetsandNewZealandincentives.•NewZealand:100%ofnewcarsandvansalestobezeroemissionsby2035.Targetszeroemissionsvehiclestomakeup100%ofurbanbussalesby2025and100%ofstockby2035.Increasezeroemissionsvehiclesto30%ofthelight-dutyvehiclefleetby2035.JapanSTEPS•Fueleconomystandardforlight-dutyvehiclestoimprovefuelefficiencyby32%to2030relativeto2016levels.APS•GreenGrowthStrategyand6thStrategicEnergyPlanaimsforsalesof100%EVs(includinghybrids)forpassengercarsby2035andforlightcommercialvehiclesby2040.•Mandatefor10%sustainableaviationfueluseby2030fornationalairlines.KoreaSTEPS•Grantsavailableforthepurchaseofprivateandcommerciallight-dutyelectricvehiclesandsubsidiesforelectricbuses.•Subsidiesforshiftingfromroadfreighttorail.•Targetofone-thirdofnewpassengercarsalestobeEVsorfuelcellelectricvehiclesby2030.APS•Targetforzeroemissionsvehiclesby2030:50%ofpassengercarsalestobehybridorplug-inhybridvehicles;and33%tobebatteryelectricorfuelcellelectricvehicles.IEA.CCBY4.0.316InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023TableB.10⊳Transportsectorpoliciesandmeasuresasmodelledbyscenarioforselectedregions/countries(continued)Region/ScenarioAssumptionscountryChinaSTEPS•Corporateaveragefuelconsumptiontargetof4.0litres/100kmin2025and3.2litres/100kmin2030.IndiaAPSSTEPS•NewEnergyAutomobileIndustryDevelopmentPlan(2021-2035):ExceedsSoutheastAsiagovernmenttargetsof20%newenergyvehiclesalesin2025and40%newenergyAPSandcleanenergy-poweredvehiclesin2030.OtherAsiaSTEPSAfricaAPS•ChinaSocietyofAutomotiveEngineerstarget:EVcarsalestoreachmorethanhalfby2035including1millionFCEVs.APSSTEPS•Extensionoftaxexemptionfornewenergyvehiclesto2027.APS•Nationalrailwayinvestments.•Installationofcharginginfrastructureformorethan20millionEVsby2025.•NewEVpolicytosupportdeploymentofcharginginfrastructure,electricmobilityinpublictransportationandpurchasesincentives.•Urbanandpublictransitinvestments.•Partialimplementationof20%bioethanolblendingtargetforgasolineand5%biodieselin2025-2026.•ExtensionofFAMEIIsubsidiesforEVsincludingsupportfor500000electricthree-wheelersand1millionelectrictwo-wheelers.•Aimtoelectrifyallbroad-gaugerailnetworksbytheendof2023.•Nationalrailwaytargetofnetzeroemissionsby2030.•Indonesia:B30programmetoincreasebiodieselblendsfrom30%to40%mandateby2023.Subsidiestosupportdeploymentofbatteryelectricvehicles.•Indonesia:Governmenttargetstohave2millionEVsinpassengerlight-dutyvehiclestockand13millionelectricmotorcyclesinthefleetby2030.•Thailand:Targetfor100%zeroemissionsvehiclesinnewsalesfrom2035.•VietNam:NetzeroGHGemissionsinthetransportsectorby2050,withagoalof100%ofroadtransporttouseelectricityandgreenenergy.•Singapore:TargettophaseoutpassengerICEvehiclesby2040.•Pakistan:Targetsfornewvehiclesales:30%ofpassengerlight-dutyvehiclesalestobeelectricby2030;90%oftrucksalestobeelectricvehiclesby2040;90%ofurbanbussalestobeelectricvehiclesby2040;and50%ofelectrictwo/three-wheelersalesby2030.•28countrieshaveadoptedtheLDVEuro3orsuperiorstandardforsecond-handvehicleimports,aswellanupperagelimitofeightyearsforimports.•Ghana:4%,16%and32%ofcarsandbusessoldtobeEVsin2025,2030and2050respectively.Notes:STEPS=StatedPoliciesScenario;APS=AnnouncedPledgesScenario.MoU=memorandumofunderstanding;GHG=greenhousegases;km=kilometre;ICE=internalcombustionengine;EVs=electricvehicles;FCEVs=fuelcellelectricvehicle;CNG=compressednaturalgas;LDV=light-dutyvehicles.Light-dutyvehiclesincludepassengercarsandlightcommercialvehicles(grossweight<3.5tonnes).Heavy-dutyvehiclesincludebothmediumfreighttrucks(grossweight3.5to15tonnes)andheavyfreighttrucks(grossweight>15tonnes).IEA.CCBY4.0.BAnnexBDesignofthescenarios317TableB.11⊳Industry-ledinitiativesandmanufacturingtargetsbyscenarioInitiativesTypeofpledgePledgeAchievementin:STEPSAPSSteelFirstMoverProcurement10%oflow-carbonsteelby2030.PartiallyFullyCoalitionNetZeroInitiativeTechnologymetmetdeploymentGlasgowProcurementBringzero-carbonprimarysteelproductionNotmetFullyBreakthroughtechnologiestomarketby2030.metNearzeroemissionssteeltobepreferredforeveryPartiallyFullymemberofthecoalition(includingEuropeanUnionmetmetandUnitedStates).CementEmissionsAchievenetzerocarbonemissionsfromoperationsNotmetPartiallyConcreteActionreductionby2050.metforClimateShippingIMODeclarationEmissionsNetzeroemissionsinternationalshippingby2050.NotFullyonZeroEmissionsreductionShippingby2050metmetAviationEmissionsNetzeroemissionsfrominternationalaviationbyNotFullyreductionIATANetZero2050.metmetInitiativeICAOinitiativeEmissionsOffsetCO2emissionsabove2019levels.PartiallyFullyreductionmetmetZeroemissionsTechnology100%ofnewMHDVstobezeroemissionsby2040.NotFullyvehiclesdeploymentmetmetGlobalMoUonZeroEmissionsMedium-dutyandHeavy-DutyVehiclesCOP26DeclarationTechnologyAllsalesofnewlight-dutyvehiclestobezeroNotFullydeploymentemissionsgloballyby2040,andbynolaterthanmetmet2035inleadingmarkets.CarmanufacturersSalestargetsLow-rangeMid-rangecorporatetargetsEVsharetoreach38-53%globally(IEAestimates).metmetNote:IMO=InternationalMaritimeOrganization;IATA=InternationalAirTransportAssociation;ICAO=InternationalCivilAviationOrganization;MoU=memorandumofunderstanding;EV=electricvehicle;MHDVs=medium-dutyandheavy-dutyvehicles.IEA.CCBY4.0.318InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023AnnexCDefinitionsThisannexprovidesgeneralinformationonterminologyusedthroughoutthisreportincluding:unitsandgeneralconversionfactors;definitionsoffuels,processesandsectors;regionalandcountrygroupings;andabbreviationsandacronyms.Unitskm2squarekilometreMhamillionhectaresAreaBatteriesWh/kgwatthoursperkilogrammeCoalDistanceMtcemilliontonnesofcoalequivalent(equals0.7Mtoe)EmissionskmkilometreEnergyppmpartspermillion(byvolume)GastCO2tonnesofcarbondioxideMassGtCO2-eqgigatonnesofcarbon-dioxideequivalent(using100-yearglobalwarmingpotentialsfordifferentgreenhousegases)IEA.CCBY4.0.kgCO2-eqkilogrammesofcarbon-dioxideequivalentgCO2/kmgrammesofcarbondioxideperkilometregCO2/kWhgrammesofcarbondioxideperkilowatt-hourkgCO2/kWhkilogrammesofcarbondioxideperkilowatt-hourEJexajoule(1joulex1018)PJpetajoule(1joulex1015)TJterajoule(1joulex1012)GJgigajoule(1joulex109)MJmegajoule(1joulex106)BoebarrelofoilequivalentToetonneofoilequivalentKtoethousandtonnesofoilequivalentMtoemilliontonnesofoilequivalentbcmebillioncubicmetresofnaturalgasequivalentMBtumillionBritishthermalunitskWhkilowatt-hourMWhmegawatt-hourGWhgigawatt-hourTWhterawatt-hourGcalgigacaloriebcmbillioncubicmetrestcmtrillioncubicmetreskgkilogrammettonne(1tonne=1000kg)ktkilotonne(1tonnex103)Mtmilliontonnes(1tonnex106)Gtgigatonne(1tonnex109)AnnexCDefinitions319MonetaryUSDmillion1USdollarx106OilUSDbillion1USdollarx109PowerUSDtrillion1USdollarx1012USD/tCO2USdollarspertonneofcarbondioxidebarrelonebarrelofcrudeoilkb/dthousandbarrelsperdaymb/dmillionbarrelsperdaymboe/dmillionbarrelsofoilequivalentperdayWwatt(1joulepersecond)kWkilowatt(1wattx103)MWmegawatt(1wattx106)GWgigawatt(1wattx109)TWterawatt(1wattx1012)GeneralconversionfactorsforenergyMultipliertoconvertto:EJGcalMtoeMBtubcmeGWh12.388x10827.782.778x105EJ4.1868x10-923.889.478x1081.163x10-71.163x10-3Gcal4.1868x10-211.163Convertfrom:Mtoe1.0551x10-910710-73.9682.932x10-811630MBtu0.0360.2522.931x10-4bcme3.6x10-68.60x10613.968x1071GWh8601x10-499992.52x10-8110.863.41x1078.6x10-53412Note:Thereisnogenerallyaccepteddefinitionofbarrelofoilequivalent(boe);typicallytheconversionfactorsusedvaryfrom7.15to7.40boepertonneofoilequivalent.Naturalgasisattributedalowheatingvalueof1MJper44.1kg.Conversionstoandfrombillioncubicmetresofnaturalgasequivalent(bcme)aregivenasrepresentativemultipliersbutmaydifferfromtheaveragevaluesobtainedbyconvertingnaturalgasvolumesbetweenIEAbalancesduetotheuseofcountry-specificenergydensities.Lowerheatingvalues(LHV)areusedthroughout.CurrencyconversionsExchangerates1USdollar(USD)(2022annualaverage)equals:BritishPound0.81ChineseYuanRenminbi6.74Euro0.95IndianRupee78.60JapaneseYen131.50Source:OECDData(database):Exchangerates(indicator),https://data.oecd.org/conversion/exchange-rates.htm,accessedOctober2023.IEA.CCBY4.0.320InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.DefinitionsAdvancedbioenergy:Sustainablefuelsproducedfromwastes,residuesandnon-foodcropfeedstocks(excludingtraditionalusesofbiomass),whicharecapableofdeliveringsignificantlifecyclegreenhousegasemissionssavingscomparedwithfossilfuelalternativesandofminimisingadversesustainabilityimpacts.Advancedbioenergyfeedstockseitherdonotdirectlycompetewithfoodandfeedcropsforagriculturallandorareonlydevelopedonlandpreviouslyusedtoproducedfoodcropfeedstocksforbiofuels.Agriculture:Includesallenergyusedonfarms,inforestryandforfishing.Agriculture,forestryandotherlanduse(AFOLU)emissions:Includesgreenhousegasemissionsfromagriculture,forestryandotherlanduse.Ammonia(NH3):Isacompoundofnitrogenandhydrogen.Itcanbeusedasafeedstockinthechemicalsector,asafuelindirectcombustionprocessesinfuelcells,andasahydrogencarrier.Tobeconsideredalow-emissionsfuel,ammoniamustbeproducedfromhydrogeninwhichtheelectricityusedtoproducethehydrogenisgeneratedfromlow-emissionsgenerationsources.Producedinsuchaway,ammoniaisconsideredalow-emissionshydrogen-basedliquidfuel.Aviation:Thistransportmodeincludesbothdomesticandinternationalflightsandtheiruseofaviationfuels.Domesticaviationcoversflightsthatdepartandlandinthesamecountry;flightsformilitarypurposesareincluded.Internationalaviationincludesflightsthatlandinacountryotherthanthedeparturelocation.Back-upgenerationcapacity:Householdsandbusinessesconnectedtoamainpowergridmayalsohaveasourceofback-uppowergenerationcapacitythat,intheeventofdisruption,canprovideelectricity.Back-upgeneratorsaretypicallyfuelledwithdieselorgasoline.Capacitycanbeaslittleasafewkilowatts.Suchcapacityisdistinctfrommini-gridandoff-gridsystemsthatarenotconnectedtoamainpowergrid.Batterystorage:Energystoragetechnologythatusesreversiblechemicalreactionstoabsorbandreleaseelectricityondemand.Biodiesel:Diesel-equivalentfuelmadefromthetransesterification(achemicalprocessthatconvertstriglyceridesinoils)ofvegetableoilsandanimalfats.Bioenergy:Energycontentinsolid,liquidandgaseousproductsderivedfrombiomassfeedstocksandbiogas.Itincludessolidbioenergy,liquidbiofuelsandbiogases.Excludeshydrogenproducedfrombioenergy,includingviaelectricityfromabiomass-firedplant,aswellassyntheticfuelsmadewithCO2feedstockfromabiomasssource.Biogas:Amixtureofmethane,CO2andsmallquantitiesofothergasesproducedbyanaerobicdigestionoforganicmatterinanoxygen-freeenvironment.Biogases:Includebothbiogasandbiomethane.Biogasoline:Includesallliquidbiofuels(advancedandconventional)usedtoreplaceCgasoline.AnnexCDefinitions321Biojetkerosene:Kerosenesubstituteproducedfrombiomass.Itincludesconversionroutessuchashydroprocessedestersandfattyacids(HEFA)andbiomassgasificationwithFischer-Tropsch.Itexcludessynthetickeroseneproducedfrombiogeniccarbondioxide.Biomethane:Biomethaneisanear-puresourceofmethaneproducedeitherby“upgrading”biogas(aprocessthatremovesanycarbondioxideandothercontaminantspresentinthebiogas)orthroughthegasificationofsolidbiomassfollowedbymethanation.Itisalsoknownasrenewablenaturalgas.Buildings:Thebuildingssectorincludesenergyusedinresidentialandservicesbuildings.Servicesbuildingsincludecommercialandinstitutionalbuildingsandothernon-specifiedbuildings.Buildingenergyuseincludesspaceheatingandcooling,waterheating,lighting,appliancesandcookingequipment.Bunkers:Includesbothinternationalmarinebunkerfuelsandinternationalaviationbunkerfuels.Capacitycredit:Proportionofthecapacitythatcanbereliablyexpectedtogenerateelectricityduringtimesofpeakdemandinthegridtowhichitisconnected.Carboncapture,utilisationandstorage(CCUS):Theprocessofcapturingcarbondioxideemissionsfromfuelcombustion,industrialprocessesordirectlyfromtheatmosphere.CapturedCO2emissionscanbestoredinundergroundgeologicalformations,onshoreoroffshore,orusedasaninputorfeedstockinmanufacturing.Carbondioxide(CO2):Agasconsistingofonepartcarbonandtwopartsoxygen.Itisanimportantgreenhouse(heat-trapping)gas.Chemicalfeedstock:Energyvectorsusedasrawmaterialstoproducechemicalproducts.Examplesarecrudeoil-basedethaneornaphthatoproduceethyleneinsteamcrackers.Cleancookingsystems:Cookingsolutionsthatreleaselessharmfulpollutants,aremoreefficientandenvironmentallysustainablethantraditionalcookingoptionsthatmakeuseofsolidbiomass(suchasathree-stonefire),coalorkerosene.Thisreferstoimprovedcookstoves,biogas/biodigestersystems,electricstoves,liquefiedpetroleumgas,naturalgasorethanolstoves.Cleanenergy:Inpower,cleanenergyincludes:renewableenergysources,nuclearpower,fossilfuelsfittedwithCCUS,hydrogenandammonia;batterystorage;andelectricitygrids.Inefficiency,cleanenergyincludesenergyefficiencyinbuildings,industryandtransport,excludingaviationbunkersanddomesticnavigation.Inend-useapplications,cleanenergyincludes:directuseofrenewables;electricvehicles;electrificationinbuildings,industryandinternationalmarinetransport;CCUSinindustryanddirectaircapture.Infuelsupply,cleanenergyincludeslow-emissionsfuels,directaircapture,andmeasurestoreducetheemissionsintensityoffossilfuelproduction.IEA.CCBY4.0.322InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.Coal:Includesbothprimarycoal,i.e.lignite,cokingandsteamcoal,andderivedfuels,e.g.patentfuel,brown-coalbriquettes,coke-ovencoke,gascoke,gasworksgas,coke-ovengas,blastfurnacegasandoxygensteelfurnacegas.Peatisalsoincluded.Coalbedmethane(CBM):Categoryofunconventionalnaturalgasthatreferstomethanefoundincoalseams.Coal-to-gas(CTG):Processinwhichcoalisfirstturnedintosyngas(amixtureofhydrogenandcarbonmonoxide)andthenintosyntheticmethane.Coal-to-liquids(CTL):Transformationofcoalintoliquidhydrocarbons.Onerouteinvolvescoalgasificationintosyngas(amixtureofhydrogenandcarbonmonoxide),whichisprocessedusingFischer-Tropschormethanol-to-gasolinesynthesis.Anotherroute,calleddirect-coalliquefaction,involvesreactingcoaldirectlywithhydrogen.Cokingcoal:Typeofcoalthatcanbeusedforsteelmaking(asachemicalreductantandasourceofheat),whereitproducescokecapableofsupportingablastfurnacecharge.Coalofthisqualityiscommonlyknownasmetallurgicalcoal.Concentratingsolarpower(CSP):Thermalpowergenerationtechnologythatcollectsandconcentratessunlighttoproducehightemperatureheattogenerateelectricity.Conventionalliquidbiofuels:Fuelsproducedfromfoodcropfeedstocks.Commonlyreferredtoasfirstgenerationbiofuelsandincludesugarcaneethanol,starch-basedethanol,fattyacidmethylester(FAME),straightvegetableoil(SVO)andhydrotreatedvegetableoil(HVO)producedfrompalm,rapeseedorsoybeanoil.Criticalminerals:Awiderangeofmineralsandmetalsthatareessentialincleanenergytechnologiesandothermoderntechnologiesandhavesupplychainsthatarevulnerabletodisruption.Althoughtheexactdefinitionandcriteriadifferamongcountries,criticalmineralsforcleanenergytechnologiestypicallyincludechromium,cobalt,copper,graphite,lithium,manganese,molybdenum,nickel,platinumgroupmetals,zinc,rareearthelementsandothercommodities,aslistedintheAnnexoftheIEAspecialreportontheRoleofCriticalMineralsinCleanEnergyTransitionsavailableat:https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions.Decompositionanalysis:Statisticalapproachthatdecomposesanaggregateindicatortoquantifytherelativecontributionofasetofpre-definedfactorsleadingtoachangeintheaggregateindicator.TheWorldEnergyOutlookusesanadditiveindexdecompositionofthetypeLogarithmicMeanDivisiaIndex(LMDI).Demand-sideintegration(DSI):Consistsoftwotypesofmeasures:actionsthatinfluenceloadshapesuchasenergyefficiencyandelectrification;andactionsthatmanageloadsuchasdemand-sideresponsemeasures.CAnnexCDefinitions323IEA.CCBY4.0.Demand-sideresponse(DSR):Describesactionswhichcaninfluencetheloadprofilesuchasshiftingtheloadcurveintimewithoutaffectingtotalelectricitydemand,orloadsheddingsuchasinterruptingdemandforashortdurationoradjustingtheintensityofdemandforacertainamountoftime.Directaircapture(DAC):AtypeofCCUSthatcapturesCO2directlyfromtheatmosphereusingliquidsolventsorsolidsorbents.ItisgenerallycoupledwithpermanentstorageoftheCO2indeepgeologicalformationsoritsuseintheproductionoffuels,chemicals,buildingmaterialsorotherproducts.WhencoupledwithpermanentgeologicalCO2storage,DACisacarbonremovaltechnology,anditisknownasdirectaircaptureandstorage(DACS).Dispatchablegeneration:Referstotechnologieswhosepoweroutputcanbereadilycontrolled,i.e.increasedtomaximumratedcapacityordecreasedtozeroinordertomatchsupplywithdemand.Electricarcfurnace:Furnacethatheatsmaterialbymeansofanelectricarc.Itisusedforscrap-basedsteelproductionbutalsoforferroalloys,aluminium,phosphorusorcalciumcarbide.Electricvehicles(EVs):Electricvehiclescompriseofbatteryelectricvehicles(BEV)andplug-inhybridvehicles.Electricitydemand:Definedastotalgrosselectricitygenerationlessownusegeneration,plusnettrade(importslessexports),lesstransmissionanddistributionlosses.Electricitygeneration:Definedasthetotalamountofelectricitygeneratedbypoweronlyorcombinedheatandpowerplantsincludinggenerationrequiredforownuse.Thisisalsoreferredtoasgrossgeneration.Electrolysis:Processofconvertingelectricenergytochemicalenergy.Mostrelevantfortheenergysectoriswaterelectrolysis,whichsplitswatermoleculesintohydrogenandoxygenmolecules.Theresultinghydrogeniscalledelectrolytichydrogen.End-usesectors:Includeindustry,transport,buildingsandother,i.e.,agricultureandothernon-energyuse.Energy-intensiveindustries:Includesproductionandmanufacturinginthebranchesofironandsteel,chemicals,non-metallicminerals(includingcement),non-ferrousmetals(includingaluminium),andpaper,pulpandprinting.Energy-relatedandindustrialprocessCO2emissions:Carbondioxideemissionsfromfuelcombustion,industrialprocesses,andfugitiveandflaringCO2fromfossilfuelextraction.Unlessotherwisestated,CO2emissionsintheWorldEnergyOutlookrefertoenergy-relatedandindustrialprocessCO2emissions.Energysectorgreenhousegas(GHG)emissions:Energy-relatedandindustrialprocessCO2emissionsplusfugitiveandventedmethane(CH4)andnitrousdioxide(N2O)emissionsfromtheenergyandindustrysectors.324InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.Energyservices:Seeusefulenergy.Ethanol:Referstobioethanolonly.Ethanolisproducedfromfermentinganybiomasshighincarbohydrates.Currentlyethanolismadefromstarchesandsugars,butsecond-generationtechnologieswillallowittobemadefromcelluloseandhemicellulose,thefibrousmaterialthatmakesupthebulkofmostplantmatter.Fischer-Tropschsynthesis:Catalyticprocesstoproducesyntheticfuels,e.g.diesel,keroseneornaphtha,typicallyfrommixturesofcarbonmonoxideandhydrogen(syngas).TheinputstoFischer-Tropschsynthesiscanbefrombiomass,coal,naturalgas,orhydrogenandCO2.Fossilfuels:Includecoal,naturalgasandoil.Gaseousfuels:Includenaturalgas,biogases,syntheticmethaneandhydrogen.Gases:Seegaseousfuels.Gas-to-liquids(GTL):Aprocessthatreactsmethanewithoxygenorsteamtoproducesyngas(amixtureofhydrogenandcarbonmonoxide)followedbyFischer-Tropschsynthesis.Theprocessissimilartothatusedincoal-to-liquids.Geothermal:Geothermalenergyisheatfromthesub-surfaceoftheearth.Waterand/orsteamcarrythegeothermalenergytothesurface.Dependingonitscharacteristics,geothermalenergycanbeusedforheatingandcoolingpurposesorbeharnessedtogeneratecleanelectricityifthetemperatureisadequate.Heat(end-use):Canbeobtainedfromthecombustionoffossilorrenewablefuels,directgeothermalorsolarheatsystems,exothermicchemicalprocessesandelectricity(throughresistanceheatingorheatpumpswhichcanextractitfromambientairandliquids).Thiscategoryreferstothewiderangeofend-uses,includingspaceandwaterheating,andcookinginbuildings,desalinationandprocessapplicationsinindustry.Itdoesnotincludecoolingapplications.Heat(supply):Obtainedfromthecombustionoffuels,nuclearreactors,large-scaleheatpumps,geothermalorsolarresources.Itmaybeusedforheatingorcooling,orconvertedintomechanicalenergyfortransportorelectricitygeneration.Commercialheatsoldisreportedundertotalfinalconsumptionwiththefuelinputsallocatedunderpowergeneration.Heavy-dutyvehicles(HDVs):Includebothmediumfreighttrucks(grossweight3.5to15tonnes)andheavyfreighttrucks(grossweight>15tonnes).Heavyindustries:Ironandsteel,chemicalsandcement.Hydrogen:Hydrogenisusedintheenergysystemasanenergycarrier,asanindustrialrawmaterial,oriscombinedwithotherinputstoproducehydrogen-basedfuels.Unlessotherwisestated,hydrogeninthisreportreferstolow-emissionshydrogen.CHydrogen-basedfuels:Seelow-emissionshydrogen-basedfuels.AnnexCDefinitions325IEA.CCBY4.0.Hydropower:Referstotheelectricityproducedinhydropowerprojects,withtheassumptionof100%efficiency.Itexcludesoutputfrompumpedstorageandmarine(tideandwave)plants.Improvedcookstoves:Intermediateandadvancedimprovedbiomasscookstoves(ISOtier>1).Itexcludesbasicimprovedstoves(ISOtier0-1).Industry:Thesectorincludesfuelusedwithinthemanufacturingandconstructionindustries.Keyindustrybranchesincludeironandsteel,chemicalandpetrochemical,cement,aluminium,andpulpandpaper.Usebyindustriesforthetransformationofenergyintoanotherformorfortheproductionoffuelsisexcludedandreportedseparatelyunderotherenergysector.Thereisanexceptionforfueltransformationinblastfurnacesandcokeovens,whicharereportedwithinironandsteel.Consumptionoffuelsforthetransportofgoodsisreportedaspartofthetransportsector,whileconsumptionbyoff-roadvehiclesisreportedunderindustry.Internationalaviationbunkers:Includethedeliveriesofaviationfuelstoaircraftforinternationalaviation.Fuelusedbyairlinesfortheirroadvehiclesareexcluded.Thedomestic/internationalsplitisdeterminedonthebasisofdepartureandlandinglocationsandnotbythenationalityoftheairline.Formanycountriesthisincorrectlyexcludesfuelsusedbydomesticallyownedcarriersfortheirinternationaldepartures.Internationalmarinebunkers:Includethequantitiesdeliveredtoshipsofallflagsthatareengagedininternationalnavigation.Theinternationalnavigationmaytakeplaceatsea,oninlandlakesandwaterways,andincoastalwaters.Consumptionbyshipsengagedindomesticnavigationisexcluded.Thedomestic/internationalsplitisdeterminedonthebasisofportofdepartureandportofarrival,andnotbytheflagornationalityoftheship.Consumptionbyfishingvesselsandbymilitaryforcesisexcludedandinsteadincludedintheresidential,servicesandagriculturecategory.Investment:Investmentisthecapitalexpenditureinenergysupply,infrastructure,end-useandefficiency.Fuelsupplyinvestmentincludestheproduction,transformationandtransportofoil,gas,coalandlow-emissionsfuels.Powersectorinvestmentincludesnewconstructionandrefurbishmentofgeneration,electricitygrids(transmission,distributionandpublicelectricvehiclechargers),andbatterystorage.Energyefficiencyinvestmentincludesefficiencyimprovementsinbuildings,industryandtransport.Otherend-useinvestmentincludesthepurchaseofequipmentforthedirectuseofrenewables,electricvehicles,electrificationinbuildings,industryandinternationalmarinetransport,equipmentfortheuseoflow-emissionsfuels,andCCUSinindustryanddirectaircapture.Dataandprojectionsreflectspendingoverthelifetimeofprojectsandarepresentedinrealtermsinyear-2022USdollarsconvertedatmarketexchangeratesunlessotherwisestated.Totalinvestmentreportedforayearreflectstheamountspentinthatyear.Levelisedcostofelectricity(LCOE):LCOEcombinesintoasinglemetricallthecostelementsdirectlyassociatedwithagivenpowertechnology,includingconstruction,financing,fuel,maintenanceandcostsassociatedwithacarbonprice.Itdoesnotincludenetworkintegrationorotherindirectcosts.326InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Light-dutyvehicles(LDVs):Includepassengercarsandlightcommercialvehicles(grossvehicleweight<3.5tonnes).Lightindustries:Includenon-energy-intensiveindustries:foodandtobacco;machinery;miningandquarrying;transportationequipment;textiles;woodharvestingandprocessing;andconstruction.Lignite:Atypeofcoalthatisusedinthepowersectormostlyinregionsnearligniteminesduetoitslowenergycontentandtypicallyhighmoisturelevels,whichgenerallymakelong-distancetransportuneconomic.DataonligniteintheWorldEnergyOutlookincludepeat.Liquidbiofuels:Liquidfuelsderivedfrombiomassorwastefeedstock,e.g.ethanol,biodieselandbiojetfuels.Theycanbeclassifiedasconventionalandadvancedbiofuelsaccordingtothecombinationoffeedstockandtechnologiesusedtoproducethemandtheirrespectivematurity.Unlessotherwisestated,biofuelsareexpressedinenergy-equivalentvolumesofgasoline,dieselandkerosene.Liquidfuels:Includeoil,liquidbiofuels(expressedinenergy-equivalentvolumesofgasolineanddiesel),syntheticoilandammonia.Low-emissionselectricity:Includesoutputfromrenewableenergytechnologies,nuclearpower,fossilfuelsfittedwithCCUS,hydrogenandammonia.Low-emissionsfuels:Includemodernbioenergy,low-emissionshydrogenandlow-emissionshydrogen-basedfuels.Low-emissionsgases:Includebiogas,biomethane,low-emissionshydrogenandlow-emissionssyntheticmethane.Low-emissionshydrogen:Hydrogenthatisproducedfromwaterusingelectricitygeneratedbyrenewablesornuclear,fromfossilfuelswithminimalassociatedmethaneemissionsandprocessedinfacilitiesequippedtoavoidCO2emissions,e.g.viaCCUSwithahighcapturerate,orderivedfrombioenergy.Inthisreport,totaldemandforlow-emissionshydrogenislargerthantotalfinalconsumptionofhydrogenbecauseitadditionallyincludeshydrogeninputstomakelow-emissionshydrogen-basedfuels,biofuelsproduction,powergeneration,oilrefining,andhydrogenproducedandconsumedonsiteinindustry.Low-emissionshydrogen-basedfuels:Includeammonia,methanolandothersynthetichydrocarbons(gasesandliquids)madefromlow-emissionshydrogen.Anycarboninputs,e.g.fromCO2,arenotfromfossilfuelsorprocessemissions.Low-emissionshydrogen-basedliquidfuels:Asubsetoflow-emissionshydrogen-basedfuelsthatincludesonlyammonia,methanolandsyntheticliquidhydrocarbons,suchassynthetickerosene.Lowerheatingvalue:Heatliberatedbythecompletecombustionofaunitoffuelwhenthewaterproducedisassumedtoremainasavapourandtheheatisnotrecovered.IEA.CCBY4.0.Marineenergy:Representsthemechanicalenergyderivedfromtidalmovement,waveCmotionoroceancurrentsandexploitedforelectricitygeneration.AnnexCDefinitions327IEA.CCBY4.0.Middledistillates:Includejetfuel,dieselandheatingoil.Mini-grids:Smallelectricgridsystems,notconnectedtomainelectricitynetworks,linkinganumberofhouseholdsand/orotherconsumers.Modernenergyaccess:Includeshouseholdaccesstoaminimumlevelofelectricity(initiallyequivalentto250kilowatt-hours(kWh)annualdemandforaruralhouseholdand500kWhforanurbanhousehold);householdaccesstolessharmfulandmoresustainablecookingandheatingfuels,andimproved/advancedstoves;accessthatenablesproductiveeconomicactivity;andaccessforpublicservices.Moderngaseousbioenergy:Seebiogases.Modernliquidbioenergy:Includesbiogasoline,biodiesel,biojetkeroseneandotherliquidbiofuels.Modernrenewables:Includeallusesofrenewableenergywiththeexceptionofthetraditionaluseofsolidbiomass.Modernsolidbioenergy:Includesallsolidbioenergyproducts(seesolidbioenergydefinition)exceptthetraditionaluseofbiomass.Italsoincludestheuseofsolidbioenergyinintermediateandadvancedimprovedbiomasscookstoves(ISOtier>1),requiringfueltobecutinsmallpiecesoroftenusingprocessedbiomasssuchaspellets.Naturalgas:Includesgasoccurringindeposits,whetherliquefiedorgaseous,consistingmainlyofmethane.Itincludesbothnon-associatedgasoriginatingfromfieldsproducinghydrocarbonsonlyingaseousform,andassociatedgasproducedinassociationwithcrudeoilproductionaswellasmethanerecoveredfromcoalmines(collierygas).Naturalgasliquids,manufacturedgas(producedfrommunicipalorindustrialwaste,orsewage)andquantitiesventedorflaredarenotincluded.Gasdataincubicmetresareexpressedonagrosscalorificvaluebasisandaremeasuredat15°Candat760mmHg(StandardConditions).Gasdataexpressedinexajoulesareonanetcalorificbasis.Thedifferencebetweenthenetandthegrosscalorificvalueisthelatentheatofvaporisationofthewatervapourproducedduringcombustionofthefuel(forgasthenetcalorificvalueis10%lowerthanthegrosscalorificvalue).Naturalgasliquids(NGLs):Liquidorliquefiedhydrocarbonsproducedinthemanufacture,purificationandstabilisationofnaturalgas.NGLsareportionsofnaturalgasrecoveredasliquidsinseparators,fieldfacilitiesorgasprocessingplants.NGLsinclude,butarenotlimitedto,ethane(whenitisremovedfromthenaturalgasstream),propane,butane,pentane,naturalgasolineandcondensates.Nearzeroemissionscapablematerialproductioncapacity:Capacitythatwillachievesubstantialemissionsreductionsfromthestart–butfallshortofnearzeroemissionsmaterialproductioninitially(seefollowingdefinition)–withplanstocontinuereducingemissionsovertimesuchthattheycouldlaterachievenearzeroemissionsproductionwithoutadditionalcapitalinvestment.328InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.Nearzeroemissionsmaterialproduction:Forsteelandcement,productionthatachievesthenearzeroGHGemissionsintensitythresholdsasdefinedinAchievingNetZeroHeavyIndustrySectorsinG7Members(IEA,2022).Thethresholdsdependonthescrapshareofmetallicinputforsteelandtheclinker-to-cementratioforcement.Forotherenergy-intensivecommoditiessuchasaluminium,fertilisersandplastics,productionthatachievesreductionsinemissionsintensityequivalenttotheconsiderationsfornearzeroemissionssteelandcement.Nearzeroemissionsmaterialproductioncapacity:Capacitythatwhenoperationalwillachievenearzeroemissionsmaterialproductionfromthestart.Networkgases:Includenaturalgas,biomethane,syntheticmethaneandhydrogenblendedinagasnetwork.Non-energy-intensiveindustries:Seeotherindustry.Non-energyuse:Theuseoffuelsasfeedstocksforchemicalproductsthatarenotusedinenergyapplications.Examplesofresultingproductsarelubricants,paraffinwaxes,asphalt,bitumen,coaltarsandtimberpreservativeoils.Non-renewablewaste:Non-biogenicwaste,suchasplasticsinmunicipalorindustrialwaste.Nuclearpower:Referstotheelectricityproducedbyanuclearreactor,assuminganaverageconversionefficiencyof33%.Off-gridsystems:Mini-gridsandstand-alonesystemsforindividualhouseholdsorgroupsofconsumersnotconnectedtoamaingrid.Offshorewind:Referstoelectricityproducedbywindturbinesthatareinstalledinopenwater,usuallyintheocean.Oil:Includesbothconventionalandunconventionaloilproduction.Petroleumproductsincluderefinerygas,ethane,liquidpetroleumgas,aviationgasoline,motorgasoline,jetfuels,kerosene,gas/dieseloil,heavyfueloil,naphtha,whitespirits,lubricants,bitumen,paraffin,waxesandpetroleumcoke.Otherenergysector:Coverstheuseofenergybytransformationindustriesandtheenergylossesinconvertingprimaryenergyintoaformthatcanbeusedinthefinalconsumingsectors.Itincludeslossesinlow-emissionshydrogenandhydrogen-basedfuelsproduction,bioenergyprocessing,gasworks,petroleumrefineries,coalandgastransformationandliquefaction.Italsoincludesenergyownuseincoalmines,inoilandgasextractionandinelectricityandheatproduction.Transfersandstatisticaldifferencesarealsoincludedinthiscategory.Fueltransformationinblastfurnacesandcokeovensarenotaccountedforintheotherenergysectorcategory.mOtahcehrininedryu,smtriyn:inAgc,atteexgtoilreys,otfrianndsupsotrrtyebqraunipcmheesntth,awtoinocdlupdroecsecsosninsgtraunctdiorne,mfoaoindinpgroincdeusssitnrgy.,CItissometimesreferredtoasnon-energy-intensiveindustry.AnnexCDefinitions329IEA.CCBY4.0.Passengercar:Aroadmotorvehicle,otherthanamopedoramotorcycle,intendedtotransportpassengers.Itincludesvansdesignedandusedprimarilytotransportpassengers.Excludedarelightcommercialvehicles,motorcoaches,urbanbusesandmini-buses/mini-coaches.Peat:Peatisacombustiblesoft,porousorcompressed,fossilsedimentarydepositofplantoriginwithhighwatercontent(upto90%intherawstate),easilycut,oflighttodarkbrowncolour.Milledpeatisincludedinthiscategory.Peatusedfornon-energypurposesisnotincludedhere.Plasticcollectionrate:Proportionofplasticsthatiscollectedforrecyclingrelativetothequantityofrecyclablewasteavailable.Plasticwaste:Referstoallpost-consumerplasticwastewithalifespanofmorethanoneyear.Powergeneration:Referstoelectricitygenerationandheatproductionfromallsourcesofelectricity,includingelectricity-onlypowerplants,heatplants,andcombinedheatandpowerplants.Bothmainactivityproducerplantsandsmallplantsthatproducefuelfortheirownuse(auto-producers)areincluded.Processemissions:CO2emissionsproducedfromindustrialprocesseswhichchemicallyorphysicallytransformmaterials.Anotableexampleiscementproduction,inwhichCO2isemittedwhencalciumcarbonateistransformedintolime,whichinturnisusedtoproduceclinker.Processheat:Theuseofthermalenergytoproduce,treatoraltermanufacturedgoods.Productiveuses:Energyusedtowardsaneconomicpurpose:agriculture,industry,servicesandnon-energyuse.Someenergydemandfromthetransportsector,e.g.freight,couldbeconsideredasproductive,butistreatedseparately.Rareearthelements(REEs):Agroupofseventeenchemicalelementsintheperiodictable,specificallythefifteenlanthanidesplusscandiumandyttrium.REEsarekeycomponentsinsomecleanenergytechnologies,includingwindturbines,electricvehiclemotorsandelectrolysers.Renewables:Includebioenergy,geothermal,hydropower,solarphotovoltaics(PV),concentratingsolarpower(CSP),windandmarine(tideandwave)energyforelectricityandheatgeneration.Residential:Energyusedbyhouseholdsincludingspaceheatingandcooling,waterheating,lighting,appliances,electronicdevicesandcooking.Roadtransport:Includesallroadvehicletypes(passengercars,two/three-wheelers,lightcommercialvehicles,busesandmediumandheavyfreighttrucks).Self-sufficiency:Correspondstoindigenousproductiondividedbytotalprimaryenergydemand.330InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023Services:Acomponentofthebuildingssector.Itrepresentsenergyusedincommercialfacilities,e.g.offices,shops,hotels,restaurants,andininstitutionalbuildings,e.g.schools,hospitals,publicoffices.Energyuseinservicesincludesspaceheatingandcooling,waterheating,lighting,appliances,cookinganddesalination.Shalegas:Naturalgascontainedwithinacommonlyoccurringrockclassifiedasshale.Shaleformationsarecharacterisedbylowpermeability,withmorelimitedabilityofgastoflowthroughtherockthanisthecasewithinaconventionalreservoir.Shalegasisgenerallyproducedusinghydraulicfracturing.Shipping/navigation:Thistransportmodeincludesbothdomesticandinternationalnavigationandtheiruseofmarinefuels.Domesticnavigationcoversthetransportofgoodsorpeopleoninlandwaterwaysandfornationalseavoyages(startsandendsinthesamecountrywithoutanyintermediateforeignport).Internationalnavigationincludesquantitiesoffuelsdeliveredtomerchantships(includingpassengerships)ofanynationalityforconsumptionduringinternationalvoyagestransportinggoodsorpassengers.Single-useplastics(ordisposableplastics):Plasticitemsusedonlyonetimebeforedisposal.Solar:Includesbothsolarphotovoltaicsandconcentratingsolarpower.Solarhomesystems(SHS):Small-scalephotovoltaicandbatterystand-alonesystems,i.e.withcapacityhigherthan10wattpeak(Wp)supplyingelectricityforsinglehouseholdsorsmallbusinesses.Theyaremostoftenusedoff-grid,butalsowheregridsupplyisnotreliable.AccesstoelectricityintheIEAdefinitionconsiderssolarhomesystemsfrom25Wpinruralareasand50Wpinurbanareas.Itexcludessmallersolarlightingsystems,e.g.solarlanternsoflessthan11Wp.Solarphotovoltaics(PV):Electricityproducedfromsolarphotovoltaiccellsincludingutility-scaleandsmall-scaleinstallations.Solidbioenergy:Includescharcoal,fuelwood,dung,agriculturalresidues,woodwasteandothersolidbiogenicwastes.Solidfuels:Includecoal,modernsolidbioenergy,traditionaluseofbiomassandindustrialandmunicipalwastes.Stand-alonesystems:Small-scaleautonomouselectricitysupplyforhouseholdsorsmallbusinesses.Theyaregenerallyusedoff-grid,butalsowheregridsupplyisnotreliable.Stand-alonesystemsincludesolarhomesystems,smallwindorhydrogenerators,dieselorgasolinegenerators.Thedifferencecomparedwithmini-gridsisinscaleandthatstand-alonesystemsdonothaveadistributionnetworkservingmultiplecostumers.Steamcoal:Atypeofcoalthatismainlyusedforheatproductionorsteam-raisinginpowerplantsand,toalesserextent,inindustry.Typically,steamcoalisnotofsufficientqualityforsteelmaking.Coalofthisqualityisalsocommonlyknownasthermalcoal.IEA.CCBY4.0.Syntheticmethane:Methanefromsourcesotherthannaturalgas,includingcoal-to-gasandClow-emissionssyntheticmethane.AnnexCDefinitions331IEA.CCBY4.0.Syntheticoil:SyntheticoilproducedthroughFischer-Tropschconversionormethanolsynthesis.ItincludesoilproductsfromCTLandGTL,andnon-ammonialow-emissionsliquidhydrogen-basedfuels.Tightoil:Oilproducedfromshaleorotherverylowpermeabilityformations,generallyusinghydraulicfracturing.Thisisalsosometimesreferredtoaslighttightoil.TightoilincludestightcrudeoilandcondensateproductionexceptfortheUnitedStates,whichincludestightcrudeoilonly(UStightcondensatevolumesareincludedinnaturalgasliquids).Totalenergysupply(TES):Representsdomesticdemandonlyandisbrokendownintoelectricityandheatgeneration,otherenergysectorandtotalfinalconsumption.Totalfinalconsumption(TFC):Isthesumofconsumptionbythevariousend-usesectors.TFCisbrokendownintoenergydemandinthefollowingsectors:industry(includingmanufacturing,mining,chemicalsproduction,blastfurnacesandcokeovens);transport;buildings(includingresidentialandservices);andother(includingagricultureandothernon-energyuse).Itexcludesinternationalmarineandaviationbunkers,exceptatworldlevelwhereitisincludedinthetransportsector.Totalfinalenergyconsumption(TFEC):Isavariabledefinedprimarilyfortrackingprogresstowardstarget7.2oftheUnitedNationsSustainableDevelopmentGoals(SDG).Itincorporatestotalfinalconsumptionbyend-usesectors,butexcludesnon-energyuse.Itexcludesinternationalmarineandaviationbunkers,exceptatworldlevel.Typicallythisisusedinthecontextofcalculatingtherenewableenergyshareintotalfinalenergyconsumption(indicatorSDG7.2.1),whereTFECisthedenominator.Traditionaluseofbiomass:Referstotheuseofsolidbiomasswithbasictechnologies,suchasathree-stonefireorbasicimprovedcookstoves(ISOtier0-1),oftenwithnoorpoorlyoperatingchimneys.Formsofbiomassusedincludewood,woodwaste,charcoalagriculturalresiduesandotherbio-sourcedfuelssuchasanimaldung.Transport:Fuelsandelectricityusedinthetransportofgoodsorpeoplewithinthenationalterritoryirrespectiveoftheeconomicsectorwithinwhichtheactivityoccurs.Thisincludes:fuelandelectricitydeliveredtovehiclesusingpublicroadsorforuseinrailvehicles;fueldeliveredtovesselsfordomesticnavigation;fueldeliveredtoaircraftfordomesticaviation;andenergyconsumedinthedeliveryoffuelsthroughpipelines.Fueldeliveredtointernationalmarineandaviationbunkersispresentedonlyattheworldlevelandisexcludedfromthetransportsectoratadomesticlevel.Trucks:Includesallsizecategoriesofcommercialvehicles:lighttrucks(grossvehicleweight<3.5tonnes);mediumfreighttrucks(grossvehicleweight3.5-15tonnes);andheavyfreighttrucks(grossvehicleweight>15tonnes).Unabatedfossilfueluse:ConsumptionoffossilfuelsinfacilitieswithoutCCUS.Usefulenergy:Referstotheenergythatisavailabletoend-userstosatisfytheirneeds.Thisisalsoreferredtoasenergyservicesdemand.Asresultoftransformationlossesatthepointofuse,theamountofusefulenergyislowerthanthecorrespondingfinalenergydemandfor332InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023mosttechnologies.Equipmentusingelectricityoftenhashigherconversionefficiencythanequipmentusingotherfuels,meaningthatforaunitofenergyconsumed,electricitycanprovidemoreenergyservices.Value-adjustedlevelisedcostofelectricity(VALCOE):Incorporatesinformationonbothcostsandthevalueprovidedtothesystem.BasedontheLCOE,estimatesofenergy,capacityandflexibilityvalueareincorporatedtoprovideamorecompletemetricofcompetitivenessforpowergenerationtechnologies.Variablerenewableenergy(VRE):Referstotechnologieswhosemaximumoutputatanytimedependsontheavailabilityoffluctuatingrenewableenergyresources.VREincludesabroadarrayoftechnologiessuchaswindpower,solarPV,run-of-riverhydro,concentratingsolarpower(wherenothermalstorageisincluded)andmarine(tidalandwave).Zerocarbon-readybuildings:Azerocarbon-readybuildingishighlyenergyefficientandeitherusesrenewableenergydirectlyoranenergysupplythatcanbefullydecarbonised,suchaselectricityordistrictheat.Zeroemissionsvehicles(ZEVs):VehiclesthatarecapableofoperatingwithouttailpipeCO2emissions(batteryelectricandfuelcellvehicles).IEA.CCBY4.0.RegionalandcountrygroupingsAdvancedeconomies:OECDregionalgroupingandBulgaria,Croatia,Cyprus1,2,MaltaandRomania.Africa:NorthAfricaandsub-SaharanAfricaregionalgroupings.AsiaPacific:SoutheastAsiaregionalgroupingandAustralia,Bangladesh,DemocraticPeople’sRepublicofKorea(NorthKorea),India,Japan,Korea,Mongolia,Nepal,NewZealand,Pakistan,ThePeople’sRepublicofChina(China),SriLanka,ChineseTaipei,andotherAsiaPacificcountriesandterritories.3Caspian:Armenia,Azerbaijan,Georgia,Kazakhstan,Kyrgyzstan,Tajikistan,TurkmenistanandUzbekistan.CentralandSouthAmerica:Argentina,PlurinationalStateofBolivia(Bolivia),BolivarianRepublicofVenezuela(Venezuela),Brazil,Chile,Colombia,CostaRica,Cuba,Curaçao,DominicanRepublic,Ecuador,ElSalvador,Guatemala,Guyana,Haiti,Honduras,Jamaica,Nicaragua,Panama,Paraguay,Peru,Suriname,TrinidadandTobago,UruguayandotherCentralandSouthAmericancountriesandterritories.4China:Includes(ThePeople'sRepublicof)ChinaandHongKong,China.DevelopingAsia:AsiaPacificregionalgroupingexcludingAustralia,Japan,KoreaandNewZealand.Emergingmarketanddevelopingeconomies:AllothercountriesnotincludedintheCadvancedeconomiesregionalgrouping.AnnexCDefinitions333FigureC.1⊳MaincountrygroupingsNote:Thismapiswithoutprejudicetothestatusoforsovereigntyoveranyterritory,tothedelimitationofinternationalfrontiersandboundariesandtothenameofanyterritory,cityorarea.Eurasia:CaspianregionalgroupingandtheRussianFederation(Russia).Europe:EuropeanUnionregionalgroupingandAlbania,Belarus,BosniaandHerzegovina,Gibraltar,Iceland,Israel5,Kosovo,Montenegro,NorthMacedonia,Norway,RepublicofMoldova,Serbia,Switzerland,Türkiye,UkraineandUnitedKingdom.EuropeanUnion:Austria,Belgium,Bulgaria,Croatia,Cyprus1,2,CzechRepublic,Denmark,Estonia,Finland,France,Germany,Greece,Hungary,Ireland,Italy,Latvia,Lithuania,Luxembourg,Malta,Netherlands,Poland,Portugal,Romania,SlovakRepublic,Slovenia,SpainandSweden.IEA(InternationalEnergyAgency):OECDregionalgroupingexcludingChile,Colombia,CostaRica,Iceland,Israel,LatviaandSlovenia.LatinAmericaandtheCaribbean(LAC):CentralandSouthAmericaregionalgroupingandMexico.MiddleEast:Bahrain,IslamicRepublicofIran(Iran),Iraq,Jordan,Kuwait,Lebanon,Oman,Qatar,SaudiArabia,SyrianArabRepublic(Syria),UnitedArabEmiratesandYemen.Non-OECD:AllothercountriesnotincludedintheOECDregionalgrouping.Non-OPEC:AllothercountriesnotincludedintheOPECregionalgrouping.NorthAfrica:Algeria,Egypt,Libya,MoroccoandTunisia.NorthAmerica:Canada,MexicoandUnitedStates.IEA.CCBY4.0.334InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023OECD(OrganisationforEconomicCo-operationandDevelopment):Australia,Austria,Belgium,Canada,Chile,Colombia,CostaRica,CzechRepublic,Denmark,Estonia,Finland,France,Germany,Greece,Hungary,Iceland,Ireland,Israel,Italy,Japan,Korea,Latvia,Lithuania,Luxembourg,Mexico,Netherlands,NewZealand,Norway,Poland,Portugal,SlovakRepublic,Slovenia,Spain,Sweden,Switzerland,Türkiye,UnitedKingdomandUnitedStates.OPEC(OrganizationofthePetroleumExportingCountries):Algeria,Angola,BolivarianRepublicofVenezuela(Venezuela),EquatorialGuinea,Gabon,Iraq,IslamicRepublicofIran(Iran),Kuwait,Libya,Nigeria,RepublicoftheCongo(Congo),SaudiArabiaandUnitedArabEmirates.OPEC+:OPECgroupingplusAzerbaijan,Bahrain,BruneiDarussalam,Kazakhstan,Malaysia,Mexico,Oman,RussianFederation(Russia),SouthSudanandSudan.SoutheastAsia:BruneiDarussalam,Cambodia,Indonesia,LaoPeople’sDemocraticRepublic(LaoPDR),Malaysia,Myanmar,Philippines,Singapore,ThailandandVietNam.ThesecountriesareallmembersoftheAssociationofSoutheastAsianNations(ASEAN).Sub-SaharanAfrica:Angola,Benin,Botswana,Cameroon,Côted’Ivoire,DemocraticRepublicoftheCongo,EquatorialGuinea,Eritrea,Ethiopia,Gabon,Ghana,Kenya,KingdomofEswatini,Madagascar,Mauritius,Mozambique,Namibia,Niger,Nigeria,RepublicoftheCongo(Congo),Rwanda,Senegal,SouthAfrica,SouthSudan,Sudan,UnitedRepublicofTanzania(Tanzania),Togo,Uganda,Zambia,ZimbabweandotherAfricancountriesandterritories.6Countrynotes1NotebyRepublicofTürkiye:Theinformationinthisdocumentwithreferenceto“Cyprus”relatestothesouthernpartoftheisland.ThereisnosingleauthorityrepresentingbothTurkishandGreekCypriotpeopleontheisland.TürkiyerecognisestheTurkishRepublicofNorthernCyprus(TRNC).UntilalastingandequitablesolutionisfoundwithinthecontextoftheUnitedNations,Türkiyeshallpreserveitspositionconcerningthe“Cyprusissue”.2NotebyalltheEuropeanUnionMemberStatesoftheOECDandtheEuropeanUnion:TheRepublicofCyprusisrecognisedbyallmembersoftheUnitedNationswiththeexceptionofTürkiye.TheinformationinthisdocumentrelatestotheareaundertheeffectivecontroloftheGovernmentoftheRepublicofCyprus.3Individualdataarenotavailableandareestimatedinaggregatefor:Afghanistan,Bhutan,CookIslands,Fiji,FrenchPolynesia,Kiribati,Macau(China),Maldives,NewCaledonia,Palau,PapuaNewGuinea,Samoa,SolomonIslands,Timor-Leste,TongaandVanuatu.4Individualdataarenotavailableandareestimatedinaggregatefor:Anguilla,AntiguaandBarbuda,Aruba,Bahamas,Barbados,Belize,Bermuda,Bonaire,SintEustatiusandSaba,BritishVirginIslands,CaymanIslands,Dominica,FalklandIslands(Malvinas),Grenada,Montserrat,SaintKittsandNevis,SaintLucia,SaintPierreandMiquelon,SaintVincentandGrenadines,SaintMaarten(Dutchpart),TurksandCaicosIslands.5ThestatisticaldataforIsraelaresuppliedbyandundertheresponsibilityoftherelevantIsraeliauthorities.TheuseofsuchdatabytheOECDand/ortheIEAiswithoutprejudicetothestatusoftheGolanHeights,EastJerusalemandIsraelisettlementsintheWestBankunderthetermsofinternationallaw.6Individualdataarenotavailableandareestimatedinaggregatefor:BurkinaFaso,Burundi,CaboVerde,CIEA.CCBY4.0.CentralAfricanRepublic,Chad,Comoros,Djibouti,Gambia,Guinea,Guinea-Bissau,Lesotho,Liberia,Malawi,Mali,Mauritania,SaoTomeandPrincipe,Seychelles,SierraLeoneandSomalia.AnnexCDefinitions335AbbreviationsandacronymsIEA.CCBY4.0.ACalternatingcurrentAFOLUagriculture,forestryandotherlanduseAPECAsia-PacificEconomicCooperationAPSAnnouncedPledgesScenarioASEANAssociationofSoutheastAsianNationsBECCSbioenergyequippedwithCCUSBEVbatteryelectricvehiclesCAAGRcompoundaverageannualgrowthrateCAFEcorporateaveragefueleconomystandards(UnitedStates)CBMcoalbedmethaneCCGTcombined-cyclegasturbineCCUScarboncapture,utilisationandstorageCDRcarbondioxideremovalCEMCleanEnergyMinisterialCH4MethaneCHPcombinedheatandpower;thetermco-generationissometimesusedCNGcompressednaturalgasCOcarbonmonoxideCO2carbondioxideCO2-eqcarbon-dioxideequivalentCOPConferenceofParties(UNFCCC)CSPconcentratingsolarpowerCTGcoal-to-gasCTLcoal-to-liquidsDACdirectaircaptureDACSdirectaircaptureandstorageDCdirectcurrentDERdistributedenergyresourcesDFIdevelopmentfinanceinstitutionsDRIdirectreducedironDSIdemand-sideintegrationDSOdistributionsystemoperatorDSRdemand-sideresponseEHOBextra-heavyoilandbitumenEMDEemergingmarketanddevelopingeconomiesEORenhancedoilrecoveryEPAEnvironmentalProtectionAgency(UnitedStates)ESGenvironmental,socialandgovernanceETSemissionstradingsystemEUEuropeanUnionEUETSEuropeanUnionEmissionsTradingSystemEVelectricvehicle336InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.FAOFoodandAgricultureOrganizationoftheUnitedNationsCFCEVfuelcellelectricvehicleFDIforeigndirectinvestment337FIDfinalinvestmentdecisionFiTfeed-intariffFOBfreeonboardGECGlobalEnergyandClimate(model)GDPgrossdomesticproductGHGgreenhousegasesGTLgas-to-liquidsH2hydrogenHDVheavy-dutyvehicleHEFAhydrogenatedestersandfattyacidsHFOheavyfueloilHVDChighvoltagedirectcurrentIAEAInternationalAtomicEnergyAgencyICEinternalcombustionengineICTinformationandcommunicationtechnologiesIEAInternationalEnergyAgencyIGCCintegratedgasificationcombined-cycleIIASAInternationalInstituteforAppliedSystemsAnalysisIMFInternationalMonetaryFundIMOInternationalMaritimeOrganizationIOCinternationaloilcompanyIPCCIntergovernmentalPanelonClimateChangeIPTindependentpowertransmissionLCOElevelisedcostofelectricityLCVlightcommercialvehicleLDVlight-dutyvehicleLEDlight-emittingdiodeLNGliquefiednaturalgasLPGliquefiedpetroleumgasLULUCFlanduse,land-usechangeandforestryMEPSminimumenergyperformancestandardsMERmarketexchangerateNDCNationallyDeterminedContributionNEANuclearEnergyAgency(anagencywithintheOECD)NGLsnaturalgasliquidsNGVnaturalgasvehicleNOCnationaloilcompanyNPVnetpresentvalueNOXnitrogenoxidesN2OnitrousoxideNZENetZeroEmissionsby2050ScenarioAnnexCDefinitionsOECDOrganisationforEconomicCo-operationandDevelopmentOPECOrganizationofthePetroleumExportingCountriesPHEVplug-inhybridelectricvehiclesPLDVpassengerlight-dutyvehiclePMparticulatematterPM2.5fineparticulatematterPPApowerpurchaseagreementPPPpurchasingpowerparityPVphotovoltaicsR&DresearchanddevelopmentRD&Dresearch,developmentanddemonstrationSAFsustainableaviationfuelSDGSustainableDevelopmentGoals(UnitedNations)SHSsolarhomesystemsSMEsmallandmediumenterprisesSO2sulphurdioxideSTEPSStatedPoliciesScenarioT&DtransmissionanddistributionTEStotalenergysupplyTFCtotalfinalconsumptionTFECtotalfinalenergyconsumptionTPAtonneperannumTPEDtotalprimaryenergydemandTSOtransmissionsystemoperatorUAEUnitedArabEmiratesUNUnitedNationsUNDPUnitedNationsDevelopmentProgrammeUNEPUnitedNationsEnvironmentProgrammeUNFCCCUnitedNationsFrameworkConventiononClimateChangeUSUnitedStatesUSGSUnitedStatesGeologicalSurveyVALCOEvalue-adjustedlevelisedcostofelectricityVREvariablerenewableenergyWACCweightedaveragecostofcapitalWEOWorldEnergyOutlookWHOWorldHealthOrganizationZEVzeroemissionsvehicleZCRBzerocarbon-readybuildingIEA.CCBY4.0.338InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexDReferencesChapter1:OverviewandkeyfindingsBIS(BankofInternationalSettlements).(2023).CreditStatistics(database)accessedJuly2023.https://www.bis.org/statistics/about_credit_stats.htmBordoff,J.andM.L.O’Sullivan(2023).TheAgeofEnergyInsecurity:HowtheFightforResourcesIsUpendingGeopolitics.https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/energy-insecurity-climate-change-geopolitics-resourcesIEA(InternationalEnergyAgency).(2023a).BuildingaUnifiedNationalPowerMarketSysteminChina.https://www.iea.org/reports/building-a-unified-national-power-market-system-in-chinaIEA.(2023b).NetZeroRoadmap:AGlobalPathwaytoKeepthe1.5°CGoalinReach.https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reachIEA.(2023c).WorldEnergyInvestment2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2023IEA.(2023d).ElectricityGridsandSecureEnergyTransitions.https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-grids-and-secure-energy-transitionsIEA.(2023e).CriticalMineralsMarketReview2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/critical-minerals-market-review-2023IEA.(2023f).GovernmentEnergySpendingTracker:June2023update.https://www.iea.org/reports/government-energy-spending-tracker-2IEA.(2023g).EnergyTechnologyPerspectives2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-technology-perspectives-2023IEA.(2022a).SolarPVGlobalSupplyChains.https://www.iea.org/reports/solar-pv-global-supply-chainsIEA.(2022b).TheFutureofHeatPumps.https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-heat-pumpsIEA.(2022c).NuclearPowerandSecureEnergyTransitions.https://www.iea.org/reports/nuclear-power-and-secure-energy-transitionsIEA.(2022d).WorldEnergyEmployment.https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-employmentIEA.(2021a).FinancingCleanEnergyTransitionsinEmergingandDevelopingEconomies.https://www.iea.org/reports/financing-clean-energy-transitions-in-emerging-and-developing-economiesIEA.(2021b).TheRoleofCriticalMineralsinCleanEnergyTransitions.https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitionsAnnexDReferences339IEA.(2019).ASEANRenewableEnergyIntegrationAnalysis.https://www.iea.org/reports/asean-renewable-energy-integration-analysisIMF(InternationalMonetaryFund).(2023).ClimateCrossroads:FiscalPoliciesinaWarmingWorld.https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2023/10/10/fiscal-monitor-october-2023NBSC(NationalBureauofStatisticsofChina).(2023).(database)accessedJuly2023.http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/OxfordEconomics.(2023).OxfordEconomicsGlobalEconomicModel,accessedJuly2023.https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/global-economic-modelUNDESA(UnitedNationsDepartmentofEconomicandSocialAffairs).(2022).https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdfChapter2:SettingthesceneArgus.(2023).Pricedata(database)accessedOctober2023.https://direct.argusmedia.com/IEA(InternationalEnergyAgency).(2023a).WorldEnergyInvestment2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2023IEA.(2023b).TheStateofCleanEnergyManufacturing.https://www.iea.org/reports/the-state-of-clean-technology-manufacturingIEA.(2023c).TrackingCleanEnergyProgress2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-clean-energy-progress-2023IEA.(2023d).ElectricityGridsandSecureEnergyTransitions.https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-grids-and-secure-energy-transitionsIEA.(2023e).NetZeroRoadmap:AGlobalPathwaytoKeepthe1.5°CGoalinReach.https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reachIEA.(2023f).CriticalMineralsMarketReview2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/critical-minerals-market-review-2023IMF(InternationalMonetaryFund).(2023).WorldEconomicOutlook:ARockyRecovery.https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/AprilMcCloskey.(2023).Dashboard(database)accessedOctober2023.https://mccloskey.opisnet.com/OxfordEconomics.(2023).OxfordEconomicsGlobalEconomicModel,accessedJuly2023.https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/global-economic-modelIEA.CCBY4.0.340InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.S&PGlobal.(2023).S&PCapitalIQPro:CommodityProfile.(database)accessedJuly2023.https://www.capitaliq.spglobal.com/UNDESA(UnitedNationsDepartmentofEconomicandSocialAffairs).(2022).WorldPopulationProspects.https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdfUSEIA(UnitedStatesEnergyInformationAgency).(2023).Petroleum&OtherLiquids(database)accessedOctober2023.https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/RBRTED.htmWorldBank.(2023a).GlobalEconomicProspects.https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/39846WorldBank.(2023b).StateandTrendsofCarbonPricing2023.https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/39796Chapter3:PathwaysfortheenergymixGlobalEnergyMonitor.(2022).GlobalGasInfrastructureTracker(database)accessedJune2023.https://globalenergymonitor.org/projects/global-gas-infrastructure-tracker/IEA(InternationalEnergyAgency).(2023a).NetZeroRoadmap:AGlobalPathwaytoKeepthe1.5°CGoalinReach.https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reachIEA.(2023b).TrackingCleanEnergyProgress2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-clean-energy-progress-2023IEA.(2023c).ElectricityGridsandSecureEnergyTransitions.https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-grids-and-secure-energy-transitionsIEA.(2023d).GlobalHydrogenReview2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2023IEA.(2023e).TowardsHydrogenDefinitionsBasedonTheirEmissionsIntensity.https://www.iea.org/reports/towards-hydrogen-definitions-based-on-their-emissions-intensityIEA.(2023f).EnergyTechnologyPerspectives2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-technology-perspectives-2023IEA.(2022a).Renewables2022.https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2022IEA.(2022b).TheFutureofHeatPumps.https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-heat-pumpsIEA.(2022c).NuclearPowerandSecureEnergyTransitions.https://www.iea.org/reports/nuclear-power-and-secure-energy-transitionsIhEtAtp.s(2:/0/2w2wdw)..Cieoaa.loirng/NreetpoZertrso/cToraanl-sinit-inoents-.zero-transitionsDAnnexDReferences341NEA(NuclearEnergyAgency).(2022).MeetingClimateChangeTargets:TheRoleofNuclearEnergy.https://www.oecd-nea.org/jcms/pl_69396/meeting-climate-change-targets-the-role-of-nuclear-energyUNFAO(UnitedNationsFoodandAgricultureOrganization).(2023).GlobalAgro-EcologicalZoning(GAEZ)(database,version4)accessedJuly2023.https://gaez.fao.org/Chapter4:Secureandpeople-centredenergytransitionsBenchmarkMineralIntelligence.(2023).Q3Forecast.https://www.benchmarkminerals.com/forecasts/ChinaMinistryofEducation.(2021).NationalBaseSituation,accessedJuly2023.http://en.moe.gov.cn/documents/statistics/2021/national/Davis,L.(2023).TheEconomicDeterminantsofHeatPumpAdoption.https://www.nber.org/papers/w31344FirstMoversCoalition.(2022).Steelcommitment.https://www.weforum.org/first-movers-coalition/sectorsIEA(InternationalEnergyAgency).(2023a).FinancingReductionsinOilandGasMethaneEmissions.https://www.iea.org/reports/financing-reductions-in-oil-and-gas-methane-emissionsIEA.(2023b).ElectricityGridsandSecureEnergyTransitions.https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-grids-and-secure-energy-transitionsIEA.(2023c).CriticalMineralsMarketReview2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/critical-minerals-market-review-2023IEA.(2023d).Accesstoelectricityimprovesslightlyin2023,butstillfarfromthepaceneededtomeetSDG7.https://www.iea.org/commentaries/access-to-electricity-improves-slightly-in-2023-but-still-far-from-the-pace-needed-to-meet-sdg7IEA.(2023e).AVisionforCleanCookingAccess.https://www.iea.org/reports/a-vision-for-clean-cooking-access-for-allIEA.(2023f).Didaffordabilitymeasureshelptameenergypricespikesforconsumersinmajoreconomies?https://www.iea.org/commentaries/did-affordability-measures-help-tame-energy-price-spikes-for-consumers-in-major-economiesIEA.(2023g).Theworld’stop1%ofemittersproduceover1000-timesmoreCO2thanthebottom1%.https://www.iea.org/commentaries/the-world-s-top-1-of-emitters-produce-over-1000-times-more-co2-than-the-bottom-1IEA.(2023h).GlobalEVOutlook2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023IEA.(2023i).WorldEnergyInvestment2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2023IEA.CCBY4.0.342InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.(2022).WorldEnergyOutlook2022.https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022IEA.(2021a).WorldEnergyOutlook2021.https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2021IEA.(2021b).FinancingCleanEnergyTransitionsinEmergingandDevelopingEconomies.https://www.iea.org/reports/financing-clean-energy-transitions-in-emerging-and-developing-economiesIPCC(IntergovernmentalPanelonClimateChange).(2021).IPCCSixthAssessmentReport,ClimateChange2021:ThePhysicalScienceBasis.https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/JATODynamics.(2021).ElectricVehicles:APricingChallenge.https://info.jato.com/electric-vehicles-a-pricing-challengeOECD(OrganisationforEconomicCo-operationandDevelopment)(2023).EducationataGlance(database)accessedJuly2023.https://stats.oecd.org/OECDStat_MetadataS&PGlobal.(2023).Metals&MiningPropertiesDatabase,accessedJune2023.https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/USNationalCenterforEducationStatistics.(2020).DigestofEducationStatistics(database)accessedJuly2023.https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/UNEP(UnitedNationsEnvironmentProgramme).(2021).GlobalMethaneAssessment.https://www.ccacoalition.org/resources/global-methane-assessment-full-reportWoodMackenzie.(2023).Q2MarketServiceOutlook(database)accessedJuly2023.https://www.woodmac.com/industry/metals-and-mining/WHO(WorldHealthOrganisation).(2021).WHOGlobalAirQualityGuidelines:Particulatematter(PM2.5andPM10),ozone,nitrogendioxide,sulphurdioxideandcarbonmonoxide.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034228WorldBank.(2022).TheGlobalHealthCostofPM2.5AirPollution.https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1816-5WorldInequalityDatabase.(2022).(database)accessedJune2023.https://wid.world/Chapter5:RegionalinsightsAl-Masri,R.andJ.Chenoweth.(2023).DesalinationcouldgivetheMiddleEastwaterwithoutdamagingmarinelife.Butitmustbemanagedcarefully.https://phys.org/news/2023-01-desalination-middle-east-marine-life.htmlBalza,L.etal.(2020).Traversingaslipperyslope:Guyana’soilopportunity.https://publications.iadb.org/en/traversing-a-slippery-slope-guyanas-oil-opportunityBenchmarkMineralsIntelligence.(2023).(database)accessedJuly2023.DIEA.CCBY4.0.https://www.benchmarkminerals.com/AnnexDReferences343IEA.CCBY4.0.BNEF(BloombergNewEnergyFinance).(2023a).SolarPVEquipmentManufacturers(database)accessedJuly2023.https://about.bnef.com/BNEF.(2023b).WindManufacturers(database)accessedJuly2023.https://about.bnef.com/IEA(InternationalEnergyAgency).(2023a).ScalingUpPrivateFinanceforCleanEnergyinEmergingandDevelopingEconomies.https://www.iea.org/reports/scaling-up-private-finance-for-clean-energy-in-emerging-and-developing-economiesIEA.(2023b).AVisionforCleanCookingAccessforAll.https://www.iea.org/reports/a-vision-for-clean-cooking-access-for-allIEA.(2023c).CostofCapitalObservatory.https://www.iea.org/reports/cost-of-capital-observatoryIEA.(2023d).Oman’shugerenewablehydrogenpotentialcanbringmultiplebenefitsinitsjourneytonetzeroemissions.https://www.iea.org/news/oman-s-huge-renewable-hydrogen-potential-can-bring-multiple-benefits-in-its-journey-to-net-zero-emissionsIEA.(2023e).TheStateofCleanTechnologyManufacturing.https://www.iea.org/reports/the-state-of-clean-technology-manufacturingIEA.(2023f).CriticalMineralsMarketReview2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/critical-minerals-market-review-2023IEA.(2022a).AfricaEnergyOutlook2022.https://www.iea.org/reports/africa-energy-outlook-2022IEA.(2022b).CoalinNetZeroTransitions.https://www.iea.org/reports/coal-in-net-zero-transitionsIEA.(2022c).AnEnergySectorRoadmaptoNetZeroEmissionsinIndonesia.https://www.iea.org/reports/an-energy-sector-roadmap-to-net-zero-emissions-in-indonesiaIEA.(2021).WorldEnergyOutlook2021.https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2021IFRI(InstitutFrançaisdesRelationsInternationales/FrenchInstituteofInternationalRelations).(2022).TheGeopoliticsofSeawaterDesalination.https://www.ifri.org/en/publications/etudes-de-lifri/geopolitics-seawater-desalinationMCI(MinistryofCommerceandIndustry,India).(2023).ImportCommodity-wiseHSCode85414012.(database)accessedJuly2023.https://tradestat.commerce.gov.in/Ray,K.etal.(2021).Anassessmentoflong-termchangesinmortalitiesduetoextremeweathereventsinIndia:Astudyof50years’data,1970–2019.WeatherandClimateExtremes,Volume32.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2021.100315SPVMarketResearch.(2023).(database)accessedJuly2023.https://www.spvmarketresearch.com/344InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.UNEP(UnitedNationsEnvironmentProgramme).(2021).UsedVehiclesandtheEnvironment:ProgressandUpdates2021.https://www.unep.org/resources/report/used-vehicles-and-environment-progress-and-updates-2021USDepartmentofEnergy.(2023).(database)accessedJuly2023.https://www.energy.gov/investWoodMackenzie.(2023).(database)accessedJuly2023.https://www.woodmac.com/industry/power-and-renewables/global-wind-service/AnnexB:DesignofthescenariosBGR(BundesanstaltfürGeowissenschaftenundRohstoffe/FederalInstituteforGeosciencesandNaturalResources).(2021).Energiestudie-DatenundEntwicklungenderdeutschenundglobalenEnergieversorgung[EnergyStudy-DataandDevelopmentsinGermanandGlobalEnergySupply].https://www.bgr.bund.de/DE/Themen/Energie/Downloads/energiestudie_2021.htmlBNEF(BloombergNewEnergyFinance).(2022).Top10EnergyStorageTrendsin2023.https://about.bnef.comBP.(2022).StatisticalReviewofWorldEnergy.https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/energy-economics/statistical-review-of-world-energy.htmlCEDIGAZ.(2022).Countryindicators(database)accessedJuly2023.https://www.cedigaz.org/databases/Cole,W.,A.WillFrazierandC.Augustine.(2021).CostProjectionsforUtilityScaleBatteryStorage:2021Update.https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy21osti/79236.pdfFinancialTimes.(2020).Electriccarcoststoremainhigherthantraditionalengines.https://www.ft.com/content/a7e58ce7-4fab-424a-b1fa-f833ce948cb7IEA(InternationalEnergyAgency).(2023).CostofCapitalObservatory.https://www.iea.org/reports/cost-of-capital-observatoryIEA.(2020).WorldEnergyOutlook2020.https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2020IEA.(2019).OffshoreWindOutlook2019.https://www.iea.org/reports/offshore‐wind‐outlook‐2019IRENA(InternationalRenewableEnergyAgency).(2023).RenewablePowerGenerationCostsin2022.https://www.irena.org/Publications/2023/Aug/Renewable-Power-Generation-Costs-in-2022DAnnexDReferences345IEA.CCBY4.0.James,B.etal.(2018).MassProductionCostEstimationofDirectH2PEMFuelCellSystemsforTransportationApplications:2018Update.https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2020/02/f71/fcto-sa-2018-transportation-fuel-cell-cost-analysis-2.pdfJATO.(2021).ElectricVehicles:APricingChallenge2021.https://info.jato.com/electric-vehicles-a-pricing-challengeOGJ(OilandGasJournal).(2022).Worldwidelookatreservesandproduction.https://www.ogj.com/ogj-survey-downloads/worldwide-production/document/17299726/worldwide-look-at-reserves-and-productionThompson,S.etal.(2018).Directhydrogenfuelcellelectricvehiclecostanalysis:Systemandhigh-volumemanufacturingdescription,validation,andoutlook.JournalofPowerSources,304-313.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2018.07.100Tsiropoulos,I.,D.TarvydasandN.Lebedeva.(2018).Li‐ionbatteriesformobilityandstationarystorageapplications.https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC113360UNDESA(UnitedNationsDepartmentofEconomicandSocialAffairs).(2022).WorldPopulationProspects2022.https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdfUNDESA.(2018).WorldUrbanisationProspects2018.https://population.un.org/wup/USEIA(UnitedStatesEnergyInformationAgency).(2023).AssumptionstotheAnnualEnergyOutlook2023:OilandGasSupplyModule.https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/assumptions/pdf/OGSM_Assumptions.pdfEIA.(2015).WorldShaleResourceAssessment.https://www.eia.gov/analysis/studies/worldshalegasEIA.(2013).TechnicallyRecoverableShaleOilandShaleGasResources:AnAssessmentof137ShaleFormationsin41CountriesOutsidetheUnitedStates.https://www.eia.gov/analysis/studies/worldshalegas/pdf/overview.pdfUSGS(UnitedStatesGeologicalSurvey).(2012a).Anestimateofundiscoveredconventionaloilandgasresourcesoftheworld.https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/fs20123042USGS.(2012b).Assessmentofpotentialadditionstoconventionaloilandgasresourcesoftheworld(outsidetheUnitedStates)fromreservegrowth.https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/fs20123052WorldBank.(2023a).WorldDevelopmentIndicators.https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicatorsWorldBank.(2023b).StateandTrendsofCarbonPricing2023.https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/39796346InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023AnnexEInputstotheGlobalEnergyandClimateModelGeneralnoteThisannexincludesreferencesofdatabasesandpublicationsusedtoprovideinputdatatotheIEAGlobalEnergyandClimate(GEC)Model.TheIEA’sowndatabasesofenergyandeconomicstatisticsprovidemuchofthedatausedintheGECModel.TheseincludeIEAstatisticsonenergysupply,transformation,demandatdetailedlevels,carbondioxideemissionsfromfuelcombustionandenergyefficiencyindicatorsthatformthebedrockoftheWorldEnergyOutlookmodellingandanalyses.SupplementaldatafromawiderangeofexternalsourcesarealsousedtocomplementIEAdataandprovideadditionaldetail.Thislistofdatabasesandpublicationsiscomprehensive,butnotexhaustive.IEA.CCBY4.0.IEAdatabasesandpublicationsIEA(InternationalEnergyAgency).(2023).CoalInformation.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/coal-information-serviceIEA.(2023).EmissionsFactors2023.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/emissions-factors-2023IEA.(2023).EnergyEfficiencyIndicators.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/energy-efficiency-indicatorsIEA.(2023).EnergyPrices.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/energy-pricesIEA.(2023).EnergyTechnologyRD&DBudgets.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/energy-technology-rd-and-d-budget-database-2IEA.(2023).GlobalEnergyReview2023:CO2Emissionsin2022.https://www.iea.org/reports/co2-emissions-in-2022IEA.(2023).GreenhouseGasEmissionsfromEnergy.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-energyIEA.(2023).MethaneTrackerDatabase2023.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/methane-tracker-database-2023IEA.(2023).MonthlyElectricityStatistics.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/monthly-electricity-statisticsIEA.(2023).MonthlyGasDataService.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/monthly-gas-data-service-2IEA.(2023).MonthlyOilDataServiceComplete.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/monthly-oil-data-service-mods-completeAnnexEInputstotheGlobalEnergyandClimateModel347IEA.(2023).NaturalGasInformation.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/natural-gas-informationIEA.(2023).Real-TimeElectricityTracker.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-tools/real-time-electricity-trackerIEA.(2023).RenewableEnergyMarketUpdate-June2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/renewable-energy-market-update-june-2023IEA.(2023).SDG7:DataandProjections.https://www.iea.org/reports/sdg7-data-and-projectionsIEA.(2023).WeatherforEnergyTracker.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/weather-for-energy-trackerIEA.(2023).WorldEnergyBalances.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/world-energy-balancesIEA.(2023).WorldEnergyInvestment2023.https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2023IEA.(2022).GlobalFuelEconomyInitiative2021DataExplorer.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-tools/global-fuel-economy-initiative-2021-data-explorerIEA.(2022).Renewables2022.https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2022IEA.(n.d.).CCUSProjectsDatabase.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/ccus-projects-databaseIEA.(n.d.).ETPCleanEnergyTechnologyGuide.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-tools/etp-clean-energy-technology-guideIEA.(n.d.).FossilFuelSubsidiesDatabase.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/fossil-fuel-subsidies-databaseIEA.(n.d).HydrogenProjectsDatabase.https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/hydrogen-projects-databaseIEA.(n.d.).PoliciesDatabase.https://www.iea.org/policies/ExternaldatabasesandpublicationsSocio-economicvariablesIMF(InternationalMonetaryFund).(2023).WorldEconomicOutlook:April2023Update.https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/AprilOxfordEconomics.(2023).OxfordEconomicsGlobalEconomicModel:July2023Update.https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/global-economic-modelIEA.CCBY4.0.348InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023UNDESA(UnitedNationsDepartmentofEconomicandSocialAffairs).(2022).WorldPopulationProspects2022.www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdfUNDESA(2018).WorldUrbanisationProspects2018.https://population.un.org/wup/WorldBank.(20223).WorldDevelopmentIndicators.https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTLPowerENTSO-E(EuropeanNetworkofTransmissionSystemOperatorsforElectricity).(2023).TransparencyPlatform(database).https://transparency.entsoe.eu/GlobalTransmission.(2020).GlobalElectricityTransmissionReportandDatabase.2020-29.https://www.globaltransmission.info/report_electricity-transmission-report-and-database-2020-29.phpIAEA(InternationalAtomicEnergyAgency).(2023).PowerReactorInformationSystem(database).https://pris.iaea.org/pris/NRGExpert(2019).ElectricityTransmissionandDistribution(database).https://www.nrgexpert.com/energy-market-research/electricity-transmission-and-distribution-database/S&PGlobal(2023).WorldElectricPowerPlants(database).S&PMarketIntelligencePlatform.https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/IEA.CCBY4.0.IndustryEuropeanUnionJointResearchCentre.EDGAR–EmissionsDatabaseforGlobalAtmosphericResearch.https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/dataset_ghg70/FastmarketsRISI(n.d.).Pulp.PaperandPackaging.https://www.risiinfo.com/industries/pulp-paper-packaging/GlobalCement.(2023).GlobalCementDirectory2023.https://www.globalcement.com/GlobalCementandConcreteAssociation.(2023).GNR2.0–GCCAinNumbers.https://gccassociation.org/sustainability-innovation/gnr-gcca-in-numbers/GlobalEnergyMonitor.(2023).GlobalSteelPlantTracker.https://globalenergymonitor.org/projects/global-steel-plant-tracker/IHSMarkit(n.d.).Chemical.https://ihsmarkit.com/industry/chemical.htmlInternationalAluminiumInstitute.(2023).WorldAluminiumStatistics.http://www.world-aluminium.org/statistics/InternationalAluminiumInstitute.(2023).TheGlobalAluminiumCycle.Ehttps://alucycle.international-aluminium.org/AnnexEInputstotheGlobalEnergyandClimateModel349IEA.CCBY4.0.IFA(InternationalFertilizerAssociation)(n.d.).IFASTAT(database).https://www.ifastat.org/METI(MinistryofEconomy,TradeandIndustry,Japan).(2023).METIStatisticsReport.https://www.meti.go.jp/english/statistics/index.htmlMMSA(MethanolMarketServicesAsia)(n.d.).(database).https://www.methanolmsa.com/NBS(NationalBureauofStatisticsofChina).(2023).StatisticalCommuniquéofThePeople'sRepublicofChinaonthe2022NationalEconomicandSocialDevelopment.http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202302/t20230227_1918979.htmlOECD(OrganisationforEconomicCo-operationandDevelopment).(2023).(database).TheGlobalPlasticsOutlookdatabase.https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/data/global-plastic-outlook_c0821f81-enS&PGlobal.(2023).PlattsGlobalPolyolefinsOutlook.https://plattsinfo.platts.com/GPO.htmlUNDESA(UnitedNationsDepartmentofEconomicandSocialAffairs)(n.d.).UNComtrade(database).https://comtrade.un.org/data/UNFAO(UnitedNationsFoodandAgricultureOrganisationoftheUnitedNations)(n.d.).FAOSTATData(database).http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#dataUSEIA(UnitedStatesEnergyInformationAdministration).(2021).ManufacturingEnergyConsumptionSurvey.https://www.eia.gov/consumption/manufacturing/data/2018/USGS(UnitedStatesGeologicalSurvey).(2023).CommodityStatisticsandInformation.NationalMineralsInformationCenter.https://www.usgs.gov/centers/nmicWorldBureauofMetalStatistics(n.d).(database).https://www.refinitiv.com/en/trading-solutions/world-bureau-metal-statisticsWorldSteelAssociation.(2023).WorldSteelinFigures2023.https://worldsteel.org/steel-topics/statistics/world-steel-in-figures-2023/TransportAIM(AviationIntegratedModel).(2020).AnOpen-SourceModelDevelopedbytheUniversityCollegeLondonEnergyInstitute.www.ucl.ac.uk/energy-models/models/aimBenchmarkMineralIntelligence(n.d.).LithiumionBatteryGigafactoryAssessmentReport.https://www.benchmarkminerals.com/market-assessments/gigafactory-assessment/EVVolumes.(2023).ElectricVehicleWorldSales(database).https://www.ev-volumes.com/ICAO(InternationalCivilAviationOrganization).(2023).AirTransportMonthlyMonitor.https://www.icao.int/sustainability/pages/air-traffic-monitor.aspx350InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023IEA.CCBY4.0.IMO(InternationalMaritimeOrganization).(2021).FourthIMOGHGStudy2020.https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Environment/Pages/Fourth-IMO-Greenhouse-Gas-Study-2020.aspxInstituteforTransportationandDevelopmentPolicy.(2022).RapidTransitDatabase.https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1uMuNG9rTGO52Vuuq6skyqmkH9U5yv1iSJDJYjH64MJM/InternationalAssociationofPublicTransport.(2021).MetroWorldStatisticsDatabase.InternationalAssociationofPublicTransport.(2020).LightRailTransitWorldStatisticsDatabase.InternationalUnionofRailways.(2022).High-SpeedLinesintheWorld2021.https://uic.org/passenger/highspeed/article/high-speed-data-and-atlasInternationalUnionofRailways.(2022).RailisaUICStatistics.https://uic-stats.uic.org/JatoDynamics(n.d.).https://www.jato.com/solutions/jato-analysis-reporting/LMCAutomotive(n.d.).LMCAutomotiveForecasting.https://lmc-auto.com/McD(n.d.).MotorCyclesData.https://www.motorcyclesdata.com/OAG(OfficialAviationGuide)(n.d.).OAG(database).https://www.oag.com/UNCTAD(UnitedNationsConferenceonTradeandDevelopment).(2022).ReviewofMaritimeTransport2022.https://unctad.org/rmt2022BuildingsandenergyaccessAHRI(AirConditioning,Heating,andRefrigerationInstitute).(2023).Statistics.https://www.ahrinet.org/analytics/statisticsCLASP(CollaborativeLabelingandApplianceStandardsProgram).(2023).Mepsy:TheAppliance&EquipmentClimateImpactCalculator.https://www.clasp.ngo/tools/mepsy/EHPA(EuropeanHeatPumpAssociation).(2023).MarketData.https://www.ehpa.org/market-data/GOGLA(GlobalAssociationfortheOff-gridSolarEnergyIndustry).(2023).GlobalOff-GridSolarMarketReport.https://www.gogla.org/global-off-grid-solar-market-reportIPCCWG1(InternationalPanelonClimateChangeWorkingGroup1).(2023).IPCCWGIInteractiveAtlas.https://interactive-atlas.ipcc.ch/JRAIA(JapanRefrigerationandAirConditioningAssociation).(2022).EstimatesofWorldAirConditionerDemandbyCountry.https://www.jraia.or.jp/english/statistics/file/World_AC_Demand.pdfEAnnexEInputstotheGlobalEnergyandClimateModel351MEMR(MinistryofEnergyandMineralResources,Indonesia).(2022).HandbookofEnergyandEconomicStatisticsofIndonesia.https://www.esdm.go.id/assets/media/content/content-handbook-of-energy-and-economic-statistics-of-indonesia-2021.pdfNationalBureauofStatisticsChina.(2023).ChinaStatisticalYearbook2022.http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/Statisticaldata/yearbook/NationalStatisticalOffice(India)(2019).DrinkingWater,Sanitation,HygieneandHousingConditionsinIndia.https://www.mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/Report_584_final_0.pdfOLADE(LatinAmericanEnergyOrganisation).(2023).ElectricityAccess(database).https://sielac.olade.org/default.aspxUSEIA(UnitedStatesEnergyInformationAdministration).(2023).2020RECS(ResidentialEnergyConsumptionSurvey).https://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/data/2020/USEIA.(2023).2018CBECS(CommercialBuildingsEnergyConsumptionSurveyData).https://www.eia.gov/consumption/commercial/USAID(UnitedStatesAgencyforInternationalDevelopment)(n.d.).DemographicandHealthSurveys(database).https://dhsprogram.com/Data/WHO(WorldHealthOrganization).(2023).HouseholdAirPollutionData(database).https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/air-pollution/household-air-pollutionWorldBank.(2023).RegulatoryIndicatorsforSustainableEnergy.https://rise.esmap.org/IEA.CCBY4.0.EnergysupplyandenergyinvestmentArgusMedia.(2023).(pricedatabase).https://direct.argusmedia.com/BGR(BundesanstaltfὕrGeowissenschaftenundRohstoffe).(2021).(GermanFederalInstituteforGeosciencesandNaturalResources2021).Energiestudie2021.DatenundEntwicklungenderDeutschenundGlobalenEnergieversorgung.[EnergyStudy2021.DataandDevelopmentsinGermanandGlobalEnergySupply].https://www.bgr.bund.de/DE/Themen/Energie/Downloads/energiestudie_2021.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4BloombergTerminal(n.d.).https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/solution/bloomberg-terminalBNEF(BloombergNewEnergyFinance).(2023).SustainableFinanceDatabase.https://about.bnef.comBP.(2022).StatisticalReviewofWorldEnergy2022.https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/energy-economics/statistical-review-of-world-energy.htmlCedigaz.(2023).Cedigaz(database).https://www.cedigaz.org/databases/CleanEnergyPipeline.(2022).(database).https://cleanenergypipeline.com/352InternationalEnergyAgencyWorldEnergyOutlook2023CRU(n.d.).Coal(database).https://www.crugroup.com/IJGlobal.(2023).Transaction(database).https://ijglobal.com/data/search-transactionsKayrros.(2023).(dataanalytics).https://www.kayrros.com/McCloskeybyOPIS.aDowJonesCompany.(2022).Coal(database).https://www.opisnet.com/commodities/coal-metals-mining/Oil&GasJournal.(2022).GlobalOilandGasReservesIncreasein2022.https://www.ogj.com/print/content/14286688RefinitivEikon.(2023).Eikon(financialdataplatform).https://eikon.thomsonreuters.com/index.htmlRystadEnergy.(2023).(database).https://www.rystadenergy.comS&PGlobal.(2023).CapitalIQ(financialdataplatform).https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/solutions/sp-capital-iq-proUSEIA(UnitedStatesEnergyInformationAdministration).(2022).(database).https://www.eia.gov/analysis/USNASA(UnitedStatesNationalAeronauticsandSpaceAdministration)LangleyResearchCenter(LaRC).(2022).PredictionofWorldwideEnergyResourceProject.https://power.larc.nasa.gov/WorldBank.(2023).PublicParticipationinInfrastructureDatabase.(database).https://ppi.worldbank.org/en/ppiIEA.CCBY4.0.AnnexEInputstotheGlobalEnergyandClimateModelE353InternationalEnergyAgency(IEA)ThisworkreflectstheviewsoftheIEASecretariatbutdoesnotnecessarilyreflectthoseoftheIEA’sindividualMembercountriesorofanyparticularfunderorcollaborator.Theworkdoesnotconstituteprofessionaladviceonanyspecificissueorsituation.TheIEAmakesnorepresentationorwarranty,expressorimplied,inrespectofthework’scontents(includingitscompletenessoraccuracy)andshallnotberesponsibleforanyuseof,orrelianceon,thework.SubjecttotheIEA’sNoticeforCC-licencedContent,thisworkislicencedunderaCreativeCommonsAttribution4.0InternationalLicence.AnnexAislicensedunderaCreativeCommonsAttribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike4.0InternationalLicence.Thisdocumentandanymapincludedhereinarewithoutprejudicetothestatusoforsovereigntyoveranyterritory,tothedelimitationofinternationalfrontiersandboundariesandtothenameofanyterritory,cityorarea.Unlessotherwiseindicated,allmaterialpresentedinfiguresandtablesisderivedfromIEAdataandanalysis.IEAPublicationsInternationalEnergyAgencyWebsite:www.iea.orgContactinformation:www.iea.org/contactTypesetinFrancebyIEA-October2023Coverdesign:IEAPhotocredits:©ShutterstockWorldEnergyOutlook2023TheWorldEnergyOutlook2023providesin-depthanalysisandstrategicinsightsintoeveryaspectoftheglobalenergysystem.Againstabackdropofgeopoliticaltensionsandfragileenergymarkets,thisyear’sreportexploreshowstructuralshiftsineconomiesandinenergyuseareshiftingthewaythattheworldmeetsrisingdemandforenergy.ThisOutlookassessestheevolvingnatureofenergysecurityfiftyyearsafterthefoundationoftheIEA.ItalsoexamineswhatneedstohappenattheCOP28climateconferenceinDubaitokeepthedooropenforthe1.5°Cgoal.And,asitdoeseveryyear,theOutlookexaminestheimplicationsoftoday’senergytrendsinkeyareasincludinginvestment,tradeflows,electrificationandenergyaccess.ThisflagshippublicationoftheInternationalEnergyAgencyistheenergyworld’smostauthoritativesourceofanalysisandprojections.Publishedeachyearsince1998,itsobjectivedataanddispassionateanalysisprovidecriticalinsightsintoglobalenergysupplyanddemandindifferentscenariosandtheimplicationsforenergysecurity,climatechangegoalsandeconomicdevelopment.