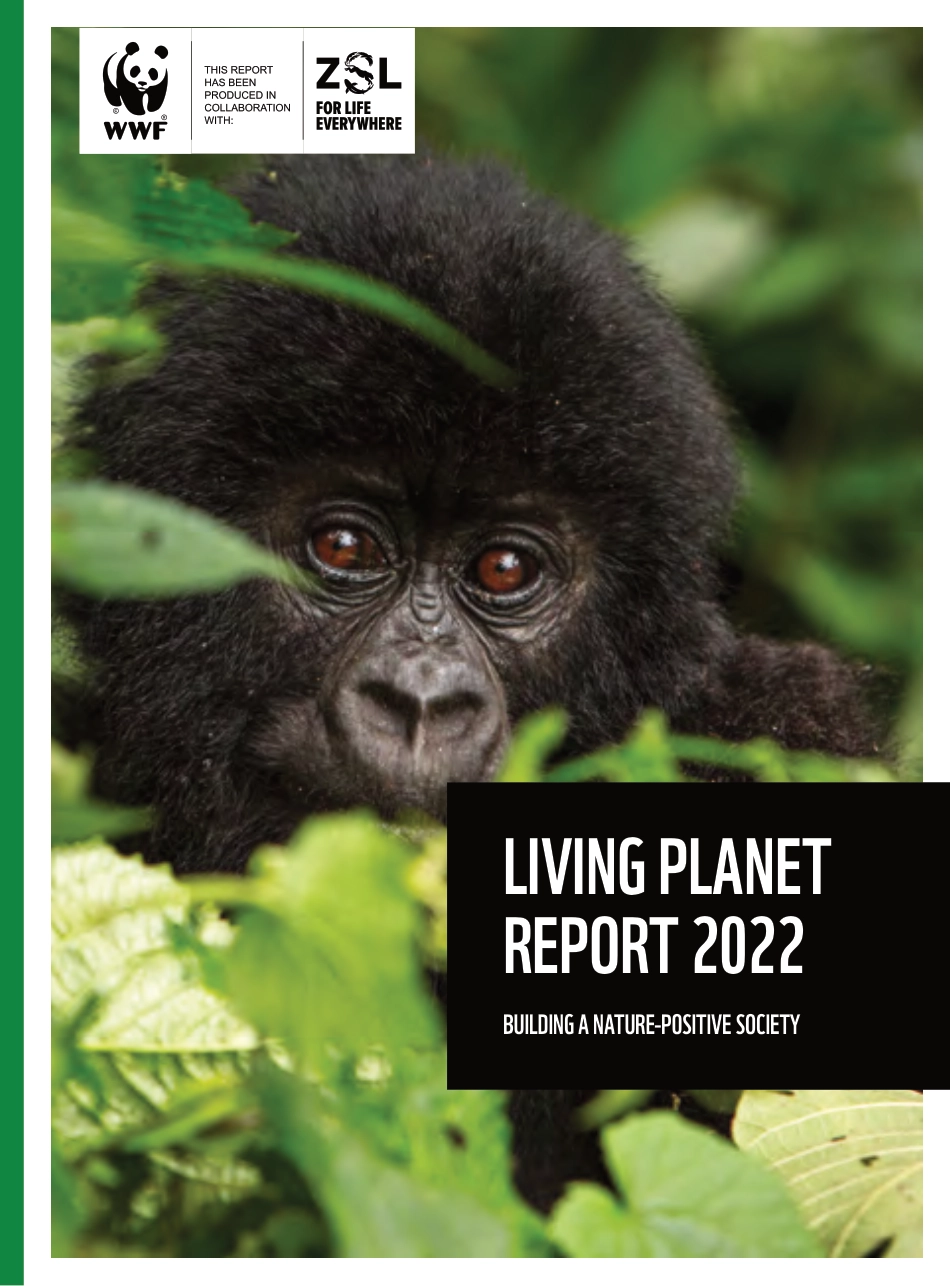

1BUILDING A NATURE-POSITIVE SOCIETYLIVING PLANET REPORT 2022WWF WWF is an independent conservation organisation, with more than 35 million followers and a global network active through local leadership in over 100 countries. WWF’s mission is to stop the degradation of the planet’s natural environment and to build a future in which people live in harmony with nature, by conserving the world’s biological diversity, ensuring that the use of renewable natural resources is sustainable, and promoting the reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption. ZSL (Zoological Society of London) Institute of Zoology ZSL is a global science-led conservation organisation helping people and wildlife live better together to restore the wonder and diversity of life everywhere. It is a powerful movement of conservationists for the living world, working together to save animals on the brink of extinction and those which could be next. ZSL manages the Living Planet Index in a collaborative partnership with WWF.Citation WWF (2022) Living Planet Report 2022 – Building a nature- positive society. Almond, R.E.A., Grooten, M., Juffe Bignoli, D. & Petersen, T. (Eds). WWF, Gland, Switzerland.Design and infographics by: peer&dedigitalesupermarktCover photograph: © Paul Robinson Mountain gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei) in the Virunga National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo.ISBN 978-2-88085-316-7Living Planet Report® and Living Planet Index® are registered trademarks of WWF International.CONTENTSEXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4FOREWORD BY MARCO LAMBERTINI 6SETTING THE SCENE 10AT A GLANCE 12CHAPTER 1: THE GLOBAL DOUBLE EMERGENCY 14CHAPTER 2: THE SPEED AND SCALE OF CHANGE 30CHAPTER 3: BUILDING A NATURE-POSITIVE SOCIETY 58THE PATH AHEAD 100REFERENCES 104...