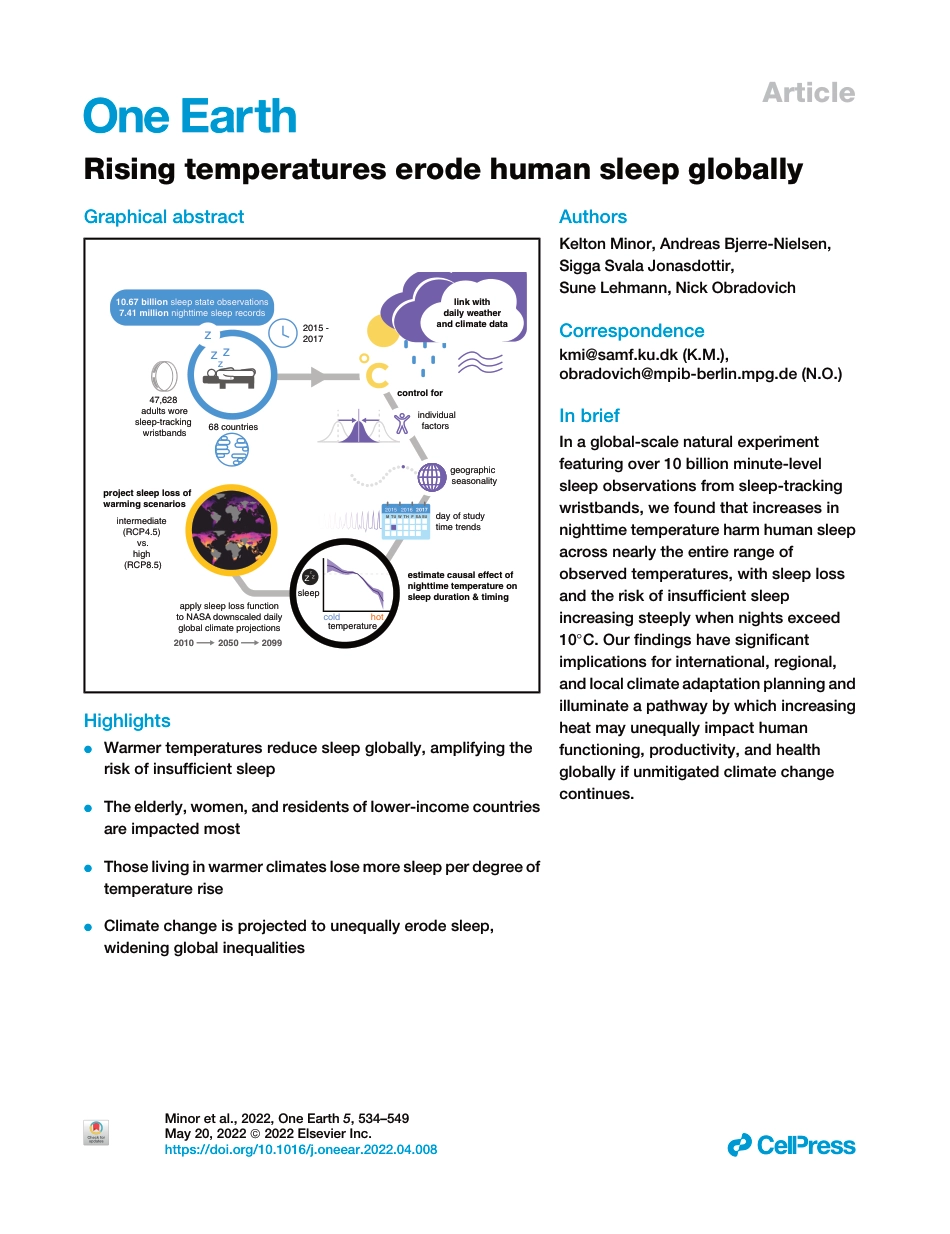

ArticleRising temperatures erode human sleep globallyGraphical abstractHighlightsd Warmer temperatures reduce sleep globally, amplifying therisk of insufficient sleepd The elderly, women, and residents of lower-income countriesare impacted mostd Those living in warmer climates lose more sleep per degree oftemperature rised Climate change is projected to unequally erode sleep,widening global inequalitiesAuthorsKelton Minor, Andreas Bjerre-Nielsen,Sigga Svala Jonasdottir,Sune Lehmann, Nick ObradovichCorrespondencekmi@samf.ku.dk (K.M.),obradovich@mpib-berlin.mpg.de (N.O.)In briefIn a global-scale natural experimentfeaturing over 10 billion minute-levelsleep observations from sleep-trackingwristbands, we found that increases innighttime temperature harm human sleepacross nearly the entire range ofobserved temperatures, with sleep lossand the risk of insufficient sleepincreasing steeply when nights exceed10�C. Our findings have significantimplications for international, regional,and local climate adaptation planning andilluminate a pathway by which increasingheat may unequally impact humanfunctioning, productivity, and healthglobally if unmitigated climate changecontinues.10.67 billion sleep state observations7.41 million nighttime sleep recordsz zz68 countries2015 -2017estimate causal effect of nighttime temperature onsleep duration & timingapply sleep loss functionto NASA downscaled dailyglobal climate projections47,628 adults woresleep-tracking wristbandscontrol for individual factors geographic seasonalityproject sleep loss ofwarming scenarioszlink withdaily weatherand climate dataM TU W TH F SA SU2015 2016 2017day of study time trendstemperaturesleephotcoldz zzintermediate (RCP4.5) vs.high (RCP8.5)205020102099Minor et al., 2022, One Earth 5, 534–549May 20, 2022 ª 2022...