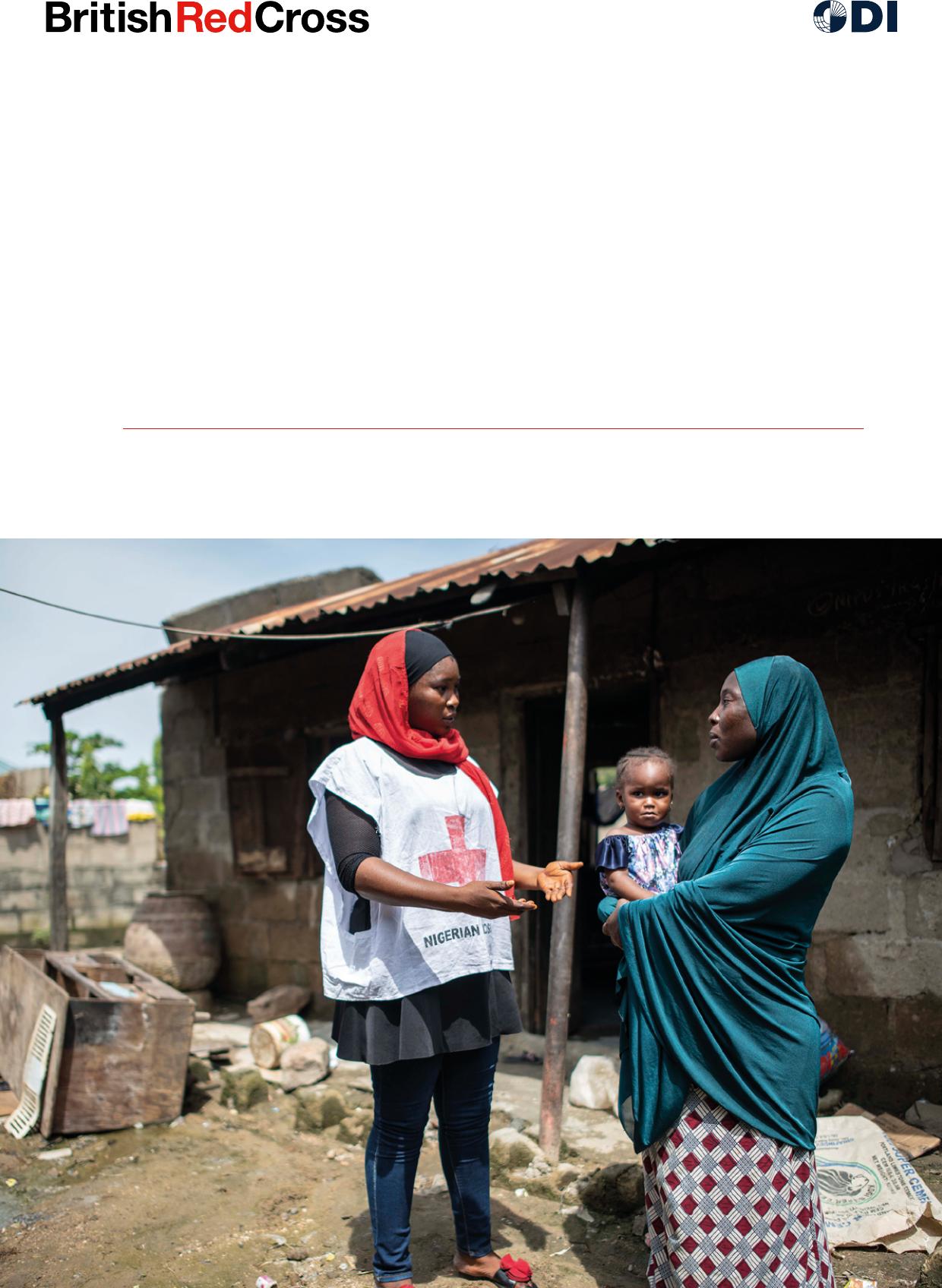

Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelFullreportiChangingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossAcknowledgementsThisreportwaswrittenbyGabrielleDaoust,YueCao,HusseinM.Sulieman,DansinéDiarra,BoukaryBarryandJimJarvie.ThisresearchwascommissionedbytheBritishRedCross.ODIandtheBritishRedCrosssincerelythankallthosewhocontributedandmadethisresearchpossible–inparticular,alltheindividualswhosharedtheirinsightsthroughsurveyparticipation,focusgroupdiscussionsandkeyinformantinterviewsinSudanandMali.InSudan,particularthanksgototheCentreforRemoteSensingandGISattheUniversityofGadarif,thedirectorandstaffoftheSudanCommissionforRefugeesandSudanHumanitarianAidinWhiteNilestateandalsothecommunityleadersinElfao,ElganaaandDabatBosin.InMali,thanksgotoKénéConseilsandallthosewhocontributedtothedatacollectioninBamakoandKayes.WeextendourappreciationandthankstotheMaliRedCrossandSudaneseRedCrescentSociety,aswellasNationalSocietiesacrossthewiderSahel,forsharingtheirassistance,knowledgeandinsights.Weexpressspecialthankstothefollowingpeoplefortheirinsights,contributionsandcommentsonthereport:EtienneBerges,LouizaChekhar,KouassiDagawa,GeorgieVanner,MariaTwerda,HugoGimbernatGuerin,JoannaMoore,AdelineSiffert(BritishRedCross),NouhoumMaiga(MaliRedCross),EddieJjemba(RedCrossRedCrescentClimateCentre),KarenHargrave(Independentconsultant),Sarah-OpitzStapletonandLeighMayhewascontributors,MauricioVazquezandCaitlinSturridge(ODI).Copyeditor:RoseCowlingDesign:vtype.co.ukCopyright2022BritishRedCrossODIredcross.org.ukodi.orgTheBritishRedCrossSociety,incorporatedbyRoyalCharter1908,isacharityregisteredinEnglandandWales(220949),Scotland(SC037738),IsleofMan(0752),Jersey(430)andGuernsey(CH142).Frontcoverphoto©IFRC/BritishRedCross.NigerianRedCrossvolunteerssupportedfloodevacuationsandprovidedpsychosocialsupportandfirstaid.NationalSocietiesparticipatingintheresearch:iiChangingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossPhoto©YukiSugiura/BritishRedCrossTheNigerRedCrosssupportspeopleinthemostvulnerablecommunitiesinNiger,onthefrontlineofclimatechange.iiiChangingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossAUAfricanUnionECOWASEconomicCommunityofWestAfricanStatesEUEuropeanUnionFGDFocusgroupdiscussionIDDRSIIGADDroughtDisasterResilienceandSustainabilityInitiativeIDMCInternalDisplacementMonitoringCentreIFRCInternationalFederationofRedCrossandRedCrescentSocietiesIGADIntergovernmentalAuthorityonDevelopmentINDCIntendedNationallyDeterminedContributionIOMInternationalOrganizationforMigrationIPCCIntergovernmentalPanelonClimateChangeNAPANationalAdaptationProgrammeofActionNGONon-governmentalorganisationPRSPPovertyReductionStrategyPaperUNUnitedNationsUNFCCCUnitedNationsFrameworkConventiononClimateChangeUNHCRUnitedNationsHighCommissionerforRefugeesAbbreviationsivChangingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTheSahelregion–thestripoflandextendingcoasttocoastfromwesttoeastAfrica–haslong-establishedpatternsofhumanmobility,largelycharacterisedbyinternalmovementwithincountriesorbetweencountries.Thismobilityhasactedasanimportantresiliencestrategyforpeople’ssurvivalandawaytocreateneweconomicopportunitiesduringtimesofbothcrisisandstability.Existingresearchsuggeststhatclimate-relatedchangesandrisksmightcontributetopressurestomoveforsomepeoplewhileconstrainingpossibilitiesformobilityforothers.FollowingalreadysignificanttransformationsintheSahel’ssemi-aridtoaridclimate,projectedchangesinrainfallandtemperaturesuggestthatclimate-relatedchallengesmayintensifyfurther.Therefore,understandingtheinfluenceofclimatechangeonmobilityintheSahelisanincreasinglyvitaltask.However,theevidenceontherelationshipbetweenclimatechangeandmigrationintheSahelremainsnascent,andtheevidencefarsparserthaninotherclimate-impactedregions.Inaddition,theresearchundertakentodatefocusesprimarilyontheimpactsofsudden-onset,short-durationclimateshocks,asopposedtoslow-onset,longer-durationchanges.CommissionedbytheBritishRedCross,thisresearchseekstofilltheseevidencegapsandtoimproveunderstandingofthelinksbetweenenvironmentalandclimatechangeandmigration,andtheirimplicationsforfuturemobilitypatternsandassociatedhumanitarianneedsandvulnerabilities.ManyofthefindingspresentedinthisreportvalidateandexpanduponexistingknowledgeonmobilityasitrelatestoenvironmentalandclimatechangeintheSahel;onpeople’scopingstrategiesandadaptationstrategies(longer-termadjustmentsthatmayenablepeopletoremaininplaceorsupportchoicesaboutmobility);andtherelationshipsbetweenthem.TheresearchconsideredMaliandSudanascase-studycountries.Ittookawidefocus,spanningbothsudden-onsetshocksandslower-onsetchanges,withexperiencesdocumentedinSudanpredominantlyreflectingtheformerandthoseinMalithelatter.Itexaminedpeople’sperceptionsoftheconnectionsbetweenclimatechangeandmigration,thewaysinwhichpeoplecopewithoradapttotheadverseconsequencesofclimatechange,andthevulnerabilities,barriers,andneedsexperiencedbythosewhousemigrationasanadaptationstrategy.ExecutivesummaryvChangingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossDatainMaliandSudanwascollectedthroughquantitativesurveys,qualitativefocusgroupdiscussions,andindividualkeyinformantinterviews.Thefollowingwerealsoanalysed:regionalandnationalpoliciesandframeworksonmigration,climate,anddevelopmentproducedbyregionalbodies,nationalgovernments,andinternationalorganisations;andexistingresearchontherelationshipsbetweenclimatechangeandmobilityintheSahelregion.Theresearchframedtheinquiryintopeople’sexperienceofclimatechangeimpactswithinabroaderperceptionofenvironmentalimpacts.Thisapproachwasdeliberatelychosen,giventhedifficultiesofisolatingthecontributionofslow-onsetclimateshiftsandwiderenvironmentalimpactsamongthemanyintersectingeconomic,political,social,andenvironmentalorclimate-relatedfactorsthatshapepeople’sdecisionstomoveorstay.Climate-relatedmigrationismulti-causal,influencedbyintersectingformsofvulnerabilityanddifferinglevelsofcapacity–eachshapedbygender,age,disabilities,andincome.Attentiontocurrentandfutureinteractionsbetweenthesedifferentfactorsisnecessarytounderstandthecomplexcausesandpatternsofmobility,andinturntoinformmorerobustpoliciesandprogrammes.Photo©SamuelTurpin/ICRCPartofHumans&ClimateChangedocumentaryprojectThisfarmerinSofara,southofMoptiinMali,saysthattheweatherhasbecomeunpredictable.Seasonsarechanging,periodsofextremeheatarelonger,andinfrequentrainsaresoheavy,whentheydocome,thattheydestroyeverything.viChangingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossKeyfindingsPerceptionsofenvironmentalchange,impactsandvulnerabilitiesVirtuallyallrespondentsinMaliandSudanobservedenvironmentalchangesintheirlocalities,withsignificanteffectsontheirsocialandeconomicconditionsandlivelihoods.Theyreportedmajornegativeclimate-relatedchangesasbeingthoseaffectingthevariability,distribution,andconcentrationofrainfall,andassociatedsecondaryhazardssuchasfloodsanddroughts.Inbothcountries,thekeynegativeenvironmentalchangesidentifiedbyrespondentswerethosemoreeasilyattributabletomanmadeactivities,includingdeforestation,reductioninorpollutionofwatersources,andsoildegradation.RespondentsinMaliandSudanoverallidentifieddecreasedagriculturalproductionanddecreasedherdsizesasthekeynegativeimpactsofenvironmentalchange,followedbysmallerfishcatches,foodinsecurity,andnegativeimpactsonemploymentandhealth.Patternsofdifferentiatedvulnerabilitiesshapetheimpactsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchange.Thereemergedtwobroadcategoriesofpeoplewhoareconsideredparticularlyvulnerableinthiscontext:farmers,herdersandfishers,duetotheoutsizedimpactsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchangeontheirlivelihoods;andothersthatarevulnerabletobothclimate-relatedandnon-climate-relatedstressesandhazards,duetowidersocio-economicfactors.Groupsidentifiedasmostvulnerabletotheimpactsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchangeincludedelderlypeople;women(especiallyinSudan),duetotheirhouseholdresponsibilities;youngmen(especiallyinMali),duetoalackofeconomicopportunities;poorerhouseholds,duetotheabsenceofreserveresources;andethnicminorities(inMali),duetoexistingsystemsofmarginalisationandinequality.KeymigrationpatternsandchangesMostrespondentsinMaliandSudanobservedthatmigrationpatternsarechangingintheirlocalities–duebothtoenvironmentalandwiderfactors.Mostrespondentsreportedincreasesinbothin-migration(i.e.migrationintorespondents’localities,fromelsewhereinthecountryorfromothercountries)andout-migration(i.e.migrationoutofrespondents’localities,towardotherpartsofthecountryortoothercountries).Inbothcountriesmost‘in-migration’isseentoinvolvepeoplefromneighbouringcountriesorwithinthesamecountry.Thesamewastrueintermsofout-migrationinSudanandSouthSudan.However,patternsofout-migrationappearmorevariedinMali,wherecross-bordermigrationtowardneighbouringcountriesandotherworldregionsweredescribedmorefrequently.InMali,changesinmigrationpatternswereobservedtohaveoccurredmainlyoverthepastfourto10years,reflectingmoregradualchangesinmigrationtrends(aswellasslower-onsetenvironmentalchanges).InSudan,changesinmigrationwereobservedtohaveoccurredmainlyinthepastonetothreeyears,reflectingmorerecentpatternsofsudden-onsethazards(i.e.flooding).Inbothcountries,migrationfromruraltourbanareas,likelylinkedtoeconomicopportunities,isseenasakeyinternalmobilitytrend–althoughrespondentsinSudanalsohighlightedtrendsinrural-to-ruralmigration,linkedtominingandviiChangingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossagriculturalopportunities.Respondentsinbothcountriesalsoobservedthatmigrationismainlytemporaryorseasonal,ratherthanpermanent–althoughthisvariedwithincountries,reflectinglocalisedpatternsofmobility.EconomicfactorswereidentifiedastheprimarymotivationformigrationinbothMaliandSudan.Environmentalfactorsweretypicallyidentifiedassecondarydrivers–althoughthereissignificantoverlapwitheconomicmotivationsgiventheimpactsofenvironmentalchangeonlivelihoods.MobilityandadaptationRespondentsinbothcountriesconsideredmigrationtobeacommonadaptationstrategy,althoughmoresoinSudan.Thislikelyreflectsdifferencesinthetypeofenvironmentalchangesandchallengesobservedbyrespondents,notablyrecentflood-induceddisplacementinSudancomparedtoslower-onsetenvironmentalchangesinMali.InMali,migrationwasdescribedasa‘lastresort’inresponsetoenvironmentalchanges,becauserespondentspreferredtostayinplace–anditisyoungpeoplewhotendtoshouldertheburdenoftakingthislastresort.‘Tippingpoints’,wherecopinginplacewasnolongerpossible,weremainlyassociatedwithsudden-onsethazards,suchasfloodingorcropfailure.Aswellasbeingaformofadaptationitself,migrationcanalsoprovidethemeanstosupportotherin-placeadaptationinitiativesthroughremittances–butthisconnectionrisksbeingoverstated,andnotallmigrantsareabletosupportsuchinitiatives.Likeothercopingandadaptationstrategies,migrationisnotequallypossibleforallpopulationgroups,witholderpeople,women,peoplewithdisabilities,andpeopleexperiencingfinancialdifficultiesfacingthegreatestbarriers.Thesesamegroupsarealsoamongthosemostvulnerabletotheimpactsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchanges.FamilyreasonsandadesiretostayinplacewerethemostfrequentlyidentifiedbarrierstomigrationinMali;thesewerealsoreportedinSudan(wherefinancialbarrierswereconsideredmostsignificant),reflectingstrongattachmentstocommunityaswellasaperceptionofpotentiallossesassociatedwithmigration.InMali,respondentshighlightedlogisticalbarrierstointernationalmigration,specificallydocumentationrequirementsandmorerestrictivemigrationpolicies.Migrationisjustoneofmanystrategiespeopleusetocopewithandadapttoclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchangesandchallenges.Overall,copingandadaptationstrategieswerereportedbymorerespondentsinMalithaninSudan,likelyreflectingdifferencesinthetypesofenvironmentalchangesandhazardsexperienced(slow-onsetenvironmentalchangesversussudden-onsetevents)andtheextentofadaptationpossible.Changesinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesortoagriculturalpracticesarecommonstrategiespeopleusetosupportin-placeadaptation,whilestrategiespeopleusetoenableshort-termcopingincludethecreationofwaterorfoodreserves,thesaleofassets,andchangesinconsumptionhabits.viiiChangingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossMigrationoutcomesandplansforreturnWhilemigrationcanenableimprovedsocialandeconomicconditions,itisalsoassociatedwithnumeroussocialandeconomicchallenges.InMali,mostrespondentswhohadthemselvesmigratedfeltthattheirsocialandeconomicconditionshadimprovedaftermigration,duetonewemploymentorbusinessopportunities,anabilitytomeettheirbasicneeds,andtheabilitytosendfundstosupporttheirfamilies.However,theyalsodescribedmigrationasbeingassociatedwithnumeroussocialandeconomicchallenges.Thiswasparticularlytrueforpeopleinvoluntarilydisplacedduetosudden-onsetenvironmentalhazardsandconflict;inthesecases,negativeimpactsincludelossofsocialstatus,resources,andproperty.InSudan,wheremostrespondentshadbeendisplacedbyseverefloods,themajorityreportedthattheirsocio-economicconditionshaddeclinedaftermigrating.WhilemostmigrantrespondentsinMaliplantoreturntoliveintheirlocalityoforigin(i.e.long-termorpermanentreturn),mostmigrantrespondentsinSudaneitherwishtoreturnbutarenotabletodoso,orhavenoplanstoreturn,forfinancialandenvironmentalreasons(forexample,becausetheirhomecommunitiesarefloodedorduetoincreasingfloodevents).Photo©GeorgeOsodi/BritishRedCrossMothers’ClubmembersoutsidetheRedCrossofChadofficeinN’Djamena,Chad.ixChangingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossPolicyresponsesExistingregionalclimate,development,andmigrationpoliciesandinitiativesacrosstheSaheltendtofocusmainlyoncross-borderandinternationalmigrationandonlong-termdisplacement,aswellasbordercontrolinitiatives.Untilrecently,lessattentionhasbeenpaidtoseasonalinternalmovement,multi-yearandcircularintra-regionalmigration,andhowclimatechangeisinfluencingtheseexistingtrends.AcrosstheSahel,policiesandlegalframeworkseithertendtoframemigrationoverallandmigrationrelatedtoenvironmentalandclimatechangelargelyasaproblemorthreattobecontrolledormanaged,ortheydonotmentiontheissueatall.Suchpoliciestendnottoacknowledgethatmigrationmayplayaroleincopingandadaptationstrategiesforclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchange.Nationalpoliciesareinfluencedbythesewiderpolicyframeworks.Theytypicallypresentmigrationasadirectresultofclimatechange,neglectingthecomplexinteractionofenvironmentalandsocio-economicdriversandvulnerabilitiesthatshapepeople’sdecisiontomove.InMaliandSudan,climateanddevelopmentpoliciesframeenvironmentalmigrationprimarilyasaproblemtobepreventedorcontrolled.InSudan,theapproachtomigrationprioritisesbordercontrolanddevelopingthecapacityoflawenforcement,whileplacingsomefocusontheprovisionofhealthandsocialservices.Assistanceforcopingandadaptationfromgovernmentandnon-governmentalorganisationsisskewedtowardsmeetingimmediateneedsaftershocks,withlesssupporttoshort-termcopingorlonger-termadaptation.Themostcommonlyreportedformsofassistancereceivedbypeoplefacingenvironmentalhazardsinresearchlocationsinbothcountrieswereformsofshort-termsupport(e.g.thedistributionoffood,cash,andnon-fooditems)that,whilealleviatingimmediateneeds,didnotdirectlyaddresskeychallengestocopingandadaptation.InMali,thissupportwasprovidedbygovernmentandbyNGOs,whileinSudan,mostifnotallassistanceinthelocationsthatweresurveyedcamefromnationalandinternationalNGOs.Differencesinaccesstoshort-termgovernmentandNGOassistanceacrossresearchlocationsmayresultfromgeographicdifferencesintheimpactsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalhazardsandchanges,aswellastheunevenallocationofthatassistance.Accesstolonger-termsupport(e.g.skillsandlivelihoodtraining,agriculturalinputs),thoughstillrelativelyuncommon,werereportedbyaslightlyhigherproportionofrespondentsinMali.Whiletrainingsupport,agriculturalinputs,andearlywarningsystemsareimportantforadaptationtoenvironmentalchanges,fewrespondentsreportedbenefitingfromthese.InMali,communitysupportinitiativesalsoplayimportantrolesinfacilitatingcopingandadaptation,alongsideorintheabsenceofsufficientgovernmentandNGOassistance.xChangingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossRecommendationsfornationalandinternationalhumanitarianactors(includingNationalRedCrossandRedCrescentSocieties)Ensurethatprogrammaticaction,organisationalnarrativesandpolicyframeworksacknowledgeandreflectthecomplexrelationshipbetweenclimatechangeandmobility:—Strengthenengagementwiththeexistingevidenceonclimatechangeandmigrationtoinformcommunicationsandadvocacystrategiesandstrategicplansonclimatechangeandmigration,ensuringthesereflectandadjusttoemergingevidence.—Pursuemoresystematicdialoguebetween,andcoordinationamong,actorsworkingindifferentcountriesandregionsofthesamecountry,giventhebroadandtransbordernatureofclimatechangeanditsimpacts.Addressvulnerabilitiesassociatedwithclimatechangeandmobility:—Targetandstrengthenroute-basedhumanitarianassistanceand(re)integrationsupporttopeoplewhomigrateinternallyandregionallyinresponsetoclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchanges.—Ensurethatsupporttakesintoaccountthedifferentialeffectsofenvironmentalandclimatechangealonglinesofgender,age,disability,livelihoodtype,andincome.Responsesshouldexplicitlyconsidertheneedsofgroupsthatareparticularlyvulnerabletotheadverseeffectsofclimatechange,andwhofacebarrierstoadaptation(includingmobility).—Supportgovernmentsandregionalorganisationstostrengthenthedevelopmentandimplementationoflawsandpoliciesaddressingclimate-relatedmobility(seebelow)throughpolicyengagementandhumanitariandiplomacy.Forexample,NationalRedCrossandRedCrescentSocietiescanbuildontheirroleashumanitarianauxiliariestonationalauthorities.—Advancepartnershipsbetweenactorswithaviewtoaddressinggapsintheevidencebaseinordertobettermeetneedsforsupport.Inthisrespect,NationalRedCrossandRedCrescentSocietieshaveauniqueroletoplayinassessingconditionsontheground.Supportadaptationandcommunityresiliencestrategieswithinclimate-vulnerablecommunities,sothatmobilityremainsachoicebutisnottheonlyoption:—Ensurethatsupportgoesbeyondshort-termneedsbystrengtheningmaterialsupportforlonger-termcopingstrategiesandlocally-ledadaptationinitiatives.—Ensurethatsupportisprovidedbasedonanunderstandingofthekeybarrierstoadaptationinspecificcommunitiesandtheneedsofdifferentgroups.Forexample,ensuringthatsupportforcopingstrategiesandadaptationinitiativesgoesbeyondtheagriculturalsector,toreflectthevariedaspirationsofyoungpeople.—Expandcommunityknowledgeofandaccesstoearlywarningsystemsandclimateinformation,tosupportpreparednessforclimate-relatedhazards,anticipatoryactionandresponses.RecommendationsxiChangingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossRecommendationsfornationalgovernmentsandregionalorganisations—Promotetheconsistentintegrationofclimate-relatedmobilityintorelevantnationalandregionalpolicyandlegalframeworksandstrategies.—Recognisemigrationinresponsetoclimatevulnerabilitiesasaformofadaptationandasinvolvingrisksandlosses,ratherthanasaproblemtobemanagedandprevented.—Avoidlookingatclimate-relatedmobilityinisolation;instead,situateitwithinthecontextofthebroaderdynamicsofenvironmentalchangethatunderpinclimate-relatedvulnerabilitiesandmigrationpatterns.—Supporttheestablishmentof,andexpandknowledgeofandaccessto,earlywarningsystemsandclimateinformationtosupportpreparednessforclimate-relatedhazards,anticipatoryactionandresponses.—Addresselementsofpolicyframeworksthatcreateorexacerbatevulnerabilitiesamongpeopleonthemoveingeneral,whichmayimpactindividualsmovinginresponsetoclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchanges.Recommendationsforinternationaldonors—Investinbuildinganevidencebasetoimproveunderstandingofhowclimatechangeinteractswithexistingandfuturepatternsanddriversofmobilityinspecificcontexts.—Addressvulnerabilitiesassociatedwithclimatechangeandmobility,includingthroughinvestmentinaddressingtheimpactsofclimatechangeonhumanitarianneedsbothformigrantsandforpeopleremaininginplace.—Ensurethatfundingthataimstoaddressvulnerabilitiesspecificallyassociatedwithclimate-relatedmigration,aswellasfundingthattargetswidervulnerabilitiesamongmigrants,takesawiderfocusonallmigrantsinsituationsofvulnerability–includinginthecontextofinternalandintra-regionalmovement.—Supportinternationalacknowledgementandconsensusthatmobilitycanbeanimportantadaptationstrategytobeenabledamongarangeofchoicesforpeopleinclimate-vulnerablecommunities.xiiChangingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossContents1.Introduction______________________________________________________________21.1ContextandResearchaims_____________________________________________21.2Structureofthereport__________________________________________________32.Researchframeworkandmethods_________________________________________42.1Researchframework____________________________________________________42.2Datasources__________________________________________________________42.3ResearchsitesinMaliandSudan________________________________________52.4Respondentdemographics______________________________________________63.TheevidenceonclimatechangeandmigrationintheSahel_________________103.1Climatevariability,environmentalchange,andfutureclimatechangerisksintheSahel______________________________________________________103.2CopingandadaptationstrategiesintheSahel___________________________113.3RelationshipsbetweenclimatechangeandmigrationintheSahel_________133.4Dimensionsofclimatevulnerabilityandconnectionstomigrationpressuresandbarriers_________________________________________________163.5Humanitarianneedsamongmigrants___________________________________194.Keyfindings:perceptionsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchangeinMaliandSudan_____________________________________________________________________214.1Observedenvironmentalchangesandperceivedcauses__________________214.2Impactsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchangesanddifferentiatedvulnerabilities____________________________________________245.Keyfindings:copingandadaptationstrategiesinMaliandSudan___________305.1Strategiestocopewithclimate-relatedenvironmentalchangesandchallenges_______________________________________________________305.2Barrierstocopingandadaptation_______________________________________345.3Assistanceforcopingandadaptation___________________________________351Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCross6.Keyfindings:migrationtrendsanddecisionsinMaliandSudan_____________416.1Overalltrendsinmigrationpatterns_____________________________________416.2Driversofmigration___________________________________________________446.3Perceivedchangestomigrationpatterns_______________________________466.4Mobilityandadaptation________________________________________________476.5Barrierstomigration___________________________________________________496.6Migrationoutcomes___________________________________________________516.7Tiesbetweenmigrantsandtheirfamiliesandcommunitiesoforigin________527.Policyframeworksandresponses_________________________________________547.1Regionalandnationalresponses_______________________________________548.Recommendations_______________________________________________________578.1Recommendationsfornationalandinternationalhumanitarianactors(includingNationalRedCrossandRedCrescentSocieties)_______________578.2Recommendationsfornationalgovernmentsandregionalorganisations____598.3Recommendationsforinternationaldonors______________________________609.References______________________________________________________________61Appendix1.Datacollectionmethods________________________________________71In-countryresearch_______________________________________________________71Datacollectionmethods__________________________________________________71Researchsites___________________________________________________________72Appendix2.Surveydatatables______________________________________________73Keyfindings:perceptionsofenvironmentalchangeinMaliandSudan_________73Keyfindings:copingandadaptationstrategiesinMaliandSudan_____________78Keyfindings:migrationdecisionsandtrajectoriesinMaliandSudan__________81Inthisreport,humanmobilityisusedasanumbrellatermtoencompassallaspectsanddriversofthemovementofpeople,includingvoluntaryinternalandcross-bordermigration,plannedandconsentedrelocation,andinvoluntaryinternalandcross-borderdisplacement(AdvisoryGrouponClimateChangeandHumanMobility,2015).Migrationreferstothemovementofpeopleawayfromtheirusualplaceofresidence,withinacountryoracrossaninternationalborder,temporarilyorpermanently,andforavarietyofreasons(whetherforcedorvoluntary)(IOM,2022a),inaccordancewithaninclusivistdefinitionof‘migrants’.Displacementreferstothemovementofpersonswhohavebeenforcedorobligedtofleeortoleavetheirhomesorplacesofhabitualresidence,especiallybecauseofenvironmentalorhuman-madedisasters,armedconflict,situationsofgeneralisedviolence,orviolationsofhumanrights.2Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCross1.1ContextandResearchaimsThebeltoflandknownastheSahelstretchesfromtheAtlanticOceaninthewesttotheRedSeaintheeastandcomprises13countries,includingMali,BurkinaFaso,Niger,Nigeria,Mauritania,ChadandSudan.Itischaracterisedbysemi-aridtoaridclimates,whichhavebeenexperiencingsignificantchanges–theresultofhumanactivitiessuchasagriculturalexpansion,aswellasglobalclimatechange.SomeSahelianpopulationshaverespondedtoenvironmentalchangesthroughmobility,whileothershavestayedinplaceandadapted.Patternsofmigrationintheregionareshapedbydeeplyrootedhistoriesofmobilityaswellasintersectingdemographic,socioeconomic,environmental,andsecuritycontexts.Thewaysinwhichclimatechangeaffectsmigration–includingtypesofcross-bordermovementrangingfromtheseasonalmovementoflivestocktomigrationforeconomicopportunitiestodisplacementafterextremeevents–highlightthetransboundarynatureofclimatechangerisksandassociatedadaptationchallenges,andtheimportanceofconsideringtheserisksandchallengesataregionalaswellasnationallevel(Opitz-Stapletonetal.,2021).RecentprojectionsoffutureclimatetrendsfromMalitoSudansuggestincreasesinannualtemperaturesandtemperature(especiallyheat)extremes,increasesinrainfallvariabilityandextremes,longerdryperiods,anddelayedrainfallonset(Holmesetal.,2022;Richardsonetal.,2022).Thesechangespresentpotentialinterconnectedrisksrelatedtowaterresourcesandwater-dependentservices,agricultureandpastoralism,fisheriesandaquaculture,foodsecurity,healthandmortality,settlementsandinfrastructure,andwiderecosystems(ibid.).Suchchangesandrisksmightcontributetoincreasedpressurestomoveforsomepeoplewhileconstrainingthepossibilitiesformobilityforothers.Existingpatternsofsocialmarginalisationandinequality,linkedtogender,age,income,disability,andmore,significantlyshapeindividuals’vulnerabilitytoclimate-relatedimpactsandwillinturnshapetheirvulnerabilitytofutureclimate-relatedrisks.Inanticipationofanincreasinglychangingclimate,itisnecessarytounderstanditsinfluenceonhumanmobilityintheSahel,whetherthatmobilityisapositiveadaptivepracticeoraresponsetocrisis.Ratherthanproblematisingmobilityandmigrationasriskstobe‘managed’or‘controlled’,migration1.Introduction3Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossshouldbeviewedsimultaneouslyaspartofawidersetofadaptiveresponsesandasinvolvingsociallosses(seeSelbyandDaoust,2021).However,framingmigrationasanecessarilyadaptiveresponseshouldalsobeavoided(Schwerdtleetal.,2020).Inthiscontext,thisresearchinvestigatesthelinksbetweenenvironmentalandclimatechangeandmigrationintheSahel,withaspecificfocusonMaliandSudan.Threebroadquestionsframethisresearch:—Howdopeopleperceivetheconnectionsbetweenclimatechangeandmigration,andwhataretheneedscreatedbyclimatechange,especiallyforvulnerablepeople?—Howdothepopulationingeneral,andvulnerablegroupsinparticular,copewithoradapttotheadverseconsequencesofclimatechange,andhowdoesmigrationfitwithinthesestrategies?—Whatarethevulnerabilities,barriers,andneedsexperiencedbythosewhousemigrationasanadaptationstrategy?ManyofthekeyfindingspresentedinthisreportvalidatefindingsfrompreviousacademicandexpertresearchontherelationshipsbetweenenvironmentalandclimatechangeandmigrationintheSahel,reinforcing(andexpandingupon)existingknowledgeontheserelationships.Thesefindingsquestionsimpleorganisationalorpolicynarrativesthatpresentadirectrelationshipbetweenclimatechangeandmigration.Theyalsohighlighttheimportanceofdrawingonamorenuancedunderstandingofclimatechange-migrationrelationshipstoinformorganisationalnarrativesandprogramming.Andtheyhighlighttheintersectingnatureofclimate-relatedandbroaderenvironmentalchanges(whichmaybedifficulttodisentangle)onpeople’smobilitydecisions.Thismorenuancedapproachwillensurethatfutureresilienceandmigrationresponseswillbemorerelevantto,andbetteralignedwith,theneedsofvulnerablecommunitiesintheSahel.1.2StructureofthereportThereportisstructuredasfollows:—Section2presentstheresearchapproachanddatacollectionmethods.—Section3examinesexistingevidenceontherelationshipsbetweenclimatechangeandmigrationintheSahel,includingfindingsonpatternsinMaliandSudan.Sections4to6presentthefindingsemergingfromthisresearch:—Section4focusesonperceptionsofenvironmentalchange,causesofthesechanges,andtheireffects(includingpatternsofvulnerability).—Section5explorescopingandadaptationresponsestoenvironmentalandclimate-relatedchanges,includingchallengesandsupport.—Section6examinesmigrationdecisionsandtrajectories,includinglinkstoenvironmentalandclimatechangeandpatternsofvulnerability.—Section7outlinesthepolicyandlegalframeworksshapingmigrationpatternsandpossibilities,andresponsesintheregionasawhole.—Section8concludesthereport,presentingemergingrecommendationsanddirectionsforward.4Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCross2.1ResearchframeworkInexaminingfactorsthatcontributetodisplacementandmigrationpressures,thedatacollectionandanalysisinthisresearchinvolvedafocusonintersectingclimate-relatedandbroaderenvironmentalchanges.AsnotedinSection3.3,existingstudiesofclimatechangeanddisplacementormigrationintheSahelfocusprimarilyontheimpactsofrapid-onset,short-durationclimate-relatedhazards(e.g.floods,storms)ratherthanslowonset,longer-durationchangesinseasonalmeantemperaturesandprecipitation.However,theeffectsofsudden-onsethazardsondisplacementarerelativelyclear,whereastheimpactsofslower-onsetshiftsonpopulationmovementaremoredifficulttodisentanglefromotherdynamicsacrosstheregion,includingsocio-economic,political,conflict-related,andbroaderenvironmentaldynamics.Understandingthesecomplexcausesandpatternsofmobilityrequiresattentiontothecurrentandfutureinteractionsbetweenclimatechangeimpactsandbroaderenvironmentalchanges.Thisunderstandingmaythen,inturn,informmorerobustpoliciesandprogrammestosupportcoping,resilience,andadaptation.Thisreport’sapproachfollowsrecommendationsfromarecentevidencereviewonclimatechangeandmigration,whichsuggeststhat‘anarrowfocusonclimatechange-relatedmigrationshouldbereplacedwith,orcomplementedby,broaderconsiderationofenvironment-migrationlinkages’,giventhat‘climatechangeisfarfromtheonlyenvironmentalfactorinmigration’(SelbyandDaoust,2021:66).2.2DatasourcesMixedmethodswereadoptedfordatacollection,withquantitativeandqualitativemethodsusedtoexploreexperiencesandperceptionsofenvironmentalandclimatechangeandassociatedresponsesandstrategies.Datawascollectedthroughi)quantitativesurveys,ii)qualitativefocusgroupsdiscussions(FGDs),andiii)individualkeyinformantinterviews.Foradetailedpresentationofthemethodsanddatacollectiontoolsutilised,seeAppendix1.TheresearchinMaliandinSudanwasledbyin-countryresearchpartners.InMali,theresearchwasledbyKénéConseils,basedinBamako,andinSudan,theresearchwasledbyateamattheCentreforRemoteSensingandGISattheUniversityofGadarif.TablessummarisingthefullsurveydatafrombothcountriesarepresentedinAppendix2.Twocategoriesofdocumentswerealsoanalysedforthisresearch.Areviewwasundertakenofexistingregionalandnationalpoliciesandframeworksonmigration,climate,anddevelopmentproducedbyregionalbodies(theAfricanUnion(AU),theEconomicCommunityofWestAfricanStates(ECOWAS),whichincludesMali;andtheInter-GovernmentalAuthorityonDevelopment(IGAD),whichincludesSudan),nationalgovernmentsinMaliandSudan,andinternationalorganisations(includingtheInternationalOrganizationforMigration(IOM),theUNHighCommissionerforRefugees,UNHCR,andtheInternationalRedCrossandRedCrescentMovement).AnanalysisofresearchontherelationshipsbetweenclimatechangeandmobilityintheSahelinthepast15yearsineitherEnglishorFrenchwasalsoconducted,toinformanunderstandingoftheexistingevidenceonthetopicandtoprovide2.Researchframeworkandmethods5Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrosssomecontextforthefindingsemergingfromprimarydatacollectioninMaliandSudan.2.3ResearchsitesinMaliandSudanDatacollectionsites(forsurveys,focusgroups,andinterviews)inMaliandSudanweredeterminedincollaborationwithin-countryresearchpartners.Siteswereselectedtorepresentbothmigrationsendingcommunitiesandmigrationdestinationcommunities,accountingforresearchpartners’existingcapacitiesandsecurity1DifferencesinthenumberofresearchsitesinMaliandSudanareafunctionofthecontext-specificapproachestakentoidentifyingtargetrespondents,combinedwiththedatacollectioncapacitiesofin-countryresearchers,andaccessconstraints.andaccessconsiderations.However,asdiscussedinSection4,researchsitesinMaliwerecharacterisedmainlybyslower-onsetenvironmentalchangeswhilethoseinSudanwerecharacterisedbysudden-onsethazards(notablyflooding),whichinfluencedrespondents’observationsregardingenvironmentalchanges,copingandadaptationpossibilities,andimplicationsformobility.Table1providesanoverviewoftheresearchlocationsandrespondentnumbersforboththesurveysandthefocusgroupdiscussionsinthetwocountries.Table1.OverviewofsurveyandFGDlocations,andno.ofrespondents,inMaliandSudan1RegionorstateResearchlocationNo.ofsurveyrespondentsNo.ofFGDrespondentsMali10088BamakoFivecommunes5044KayesNinelocalities5044Sudan165118GadarifElfao5033WhiteNileDabatBosin5548Elganaa60376Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossResearchsitesinMaliInMali,surveydatawascollectedin14sitesintworegions:sendingandtransitareasintheregionofKayes(focusingoncommunitiesknownforhighlevelsofinternalandinternationalout-migration)anddestinationareasforbothinternalandcross-bordermigrationinBamako.Kayeshaslongbeenasiteoftransitforinternalandcross-bordermigrantsduetoitspositioninWestAfricantransportnetworksanditsproximitytoborderswithSenegalandMauritania,aswellasGuinea(Lombard2008).Theregionishometoapopulationofroughly661,000,with23%residinginurbanareasand77%inruralareas.Bamako,thecountry’scapital,ishometoover2.4millionpeople.ResearchsitesinSudanInSudan,datawascollectedinElfaoinGadarifstateandDabatBosinandElganaainWhiteNilestate.ThetownofElfaoisnearalargenationalirrigatedagriculturalschemethathasattractedmanypeopleasagriculturalworkers.Elfaoalsohostsacampforpeopleinternallydisplacedduetorecentflooding.ThevillageofElganaarepresentsahostcommunityforcross-borderrefugeesfromSouthSudan,duetoitslocationneartheSudan-SouthSudanborder.ThevillageofDabatBosinisatransitlocation,includingforSouthSudanesemigrantsdisplacedduetorecentfloodinginUpperNilestate,SouthSudan.TheseSouthSudanesecommunitieshavebeenrelocatedtodifferentrefugeecampsmanagedbytheSudaneseCommissionforRefugees(COR)andsupportedbytheUNHCRandothernationalandinternationalNGOs.Someresidentshadexperiencedtwoflooddisasterswithinsixmonths:firstinElganaarefugeecampin2021andtheninDabatBosinafterrelocatingfromElganaa.KeyinformantinterviewsAlongsidetheFGDs,individualinterviewswereconductedwithgovernmentofficialsandrepresentativesofnationalandinternationalnon-governmentalorganisations(NGOs)andcivilsocietyorganisations(CSOs)atnationalandsubnationallevels.Theinterviewsfocusedonperceptionsofmigrationpatternsandmotivations,patternsofenvironmentalchange,relationshipsbetweenenvironmentalorclimatechangeandmigration,andpolicyandprogrammeresponses.InMali,individualinterviewswereconductedwithfivemunicipalandregionalgovernmentofficialsandsixrepresentativesofinternationalandnationalNGOsandCSOs(includingmigration-,development-,andwomen–andyouth-focusedorganisations),includingtheMaliRedCross,inBamakoandKayes.InSudan,interviewswereconductedwithrepresentativesfromtheSudaneseRedCrescentSociety.2.4RespondentdemographicsTable2providesanoverviewofthesocio-demographiccharacteristicsofsurveyparticipantsinthetwocountries.RespondentsinMali.InMali,thelowproportionofwomenamongsurveyrespondentsmayreflectthefocusonmigrants,who(asdiscussedinSection6.5)aremainlymen,andtheimplementationofthesurveyviaheadsofhousehold.Mostrespondentswererelativelyyoung,aged45oryounger.Datacollectionviafocusgroupsenabledamorerepresentativerangeofperspectives,withseparategroupsheldwithwomenandmenofdifferentagesandwithpeoplewithdisabilities(seeAppendix1).MostrespondentsinBamakowereinternalmigrants.Surveylocationswereselected7Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrosstorepresentmigrantsending,transit,anddestinationareas(asdescribedabove),whichlikelyaffectsthefindingsonpatternsofmobility,includingthelikelihoodofidentifyingmigrationasanadaptationstrategy.Professionsvariedacrossresearchsites,withmorerespondentsinvolvedinagricultureinKayesandintradeinBamako.RespondentsinSudan.InSudan,surveyrespondentsinDabatBosinandElfaowereprimarilywomen,becauseSouthSudanesemenstayedintheirlocalityoforigintolookafterpropertyaftertheflood,andmostyoungmeninElfaohadout-migratedlookingforwork.Mostrespondentswereyoung,withafewagedover55years.DisabilitieswerealsomoreprevalentamongrespondentsinSudan(11%),potentiallyattributabletothemanyyearsofwar.Mostrespondentswereinvolvedinsubsistencefarming,whilemostwomenalsoengagedinhouseholdwork.Photo©SamuelTurpin/ICRCPartofHumans&ClimateChangedocumentaryprojectMamadou’sherdgrazesonthebedoftheYaméRiverinMali.ItisthefullrainyseasoninAugust,buttheYamériver,atributaryoftheNiger,isstilldry.8Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTable2.Socio-demographiccharacteristicsofsurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanCharacteristicsMaliSudanTotal(N=100)Bamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)Total(N=165)DabatBosin,WhiteNile(n=55)Elganaa,WhiteNile(n=60)Elfao,Gadarif(n=50)Respondent’sgenderMan81%70%94%44%33%70%24%Woman19%30%6%56%67%30%76%DisabilitystatusNodisabilityreported90%98%82%95%89%98%98%Disability10%2%18%5%11%2%2%Respondent’sageYoungerthan181%2%01%2%02%18to2410%14%6%18%18%17%18%25to3427%42%12%27%35%28%16%35to4422%28%16%24%16%28%26%45to5414%14%14%16%16%10%22%55orolder26%052%15%13%17%14%Respondent’shouseholdsize1to5people19%34%4%39%55%32%32%6to10people33%46%20%42%33%42%54%Morethan1048%20%76%18%13%27%14%Respondent’smaritalstatusSingle16%22%10%17%11%22%18%Married79%72%86%74%76%75%70%Divorced2%4%02%2%2%2%Widowed3%2%4%6%9%010%Respondent’seducationlevelNoformaleducation27%32%22%45%62%28%46%Qur’anicstudies25%18%32%4%02%12%Primaryeducation28%36%20%34%25%40%36%Secondaryeducation14%14%14%14%11%23%6%Highereducation6%012%2%2%5%0Respondent’sprofessionAgriculture25%16%34%48%47%60%34%Fishing6%4%8%25%62%13%09Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossCharacteristicsMaliSudanTotal(N=100)Bamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)Total(N=165)DabatBosin,WhiteNile(n=55)Elganaa,WhiteNile(n=60)Elfao,Gadarif(n=50)Herding6%4%8%11%18%13%0Householdwork12%22%2%56%67%30%76%Trade34%46%22%14%22%8%12%Transport12%16%8%2%2%2%2%Employee19%24%14%2%008%Other†13%8%18%25%25%17%36%Respondent’stimeincurrentlocalityEntirelife37%074%36%0100%0%Lessthan1year5%8%2%45%51%094%1to5years19%36%2%18%47%06%6to10years16%28%4%000011to15years8%10%6%0000Morethan15years15%18%12%0000Respondent’smigrationstatusResidentinlocalityoforigin36%072%36%0100%0Internalmigrant58%92%24%30%00100%Transhumance1%2%00000Fromanothercountry‡5%6%4%33%100%00MainactivitiesintheresearchlocationSubsistenceagriculture92%94%90%99%Commercialagriculture29%30%28%10%Subsistencefishing15%6%24%59%Commercialfishing16%10%22%10%Subsistenceherding47%48%46%79%Commercialherding39%38%40%4%Trade57%70%44%26%Mining22%22%22%3%Transport13%2%24%2%Disabilitiesincludedphysical,sight-related,andhearing-relateddisabilities†OtherincludeshandicraftsinMali‡�InMali,migrantrespondentscamefromTogo,Senegal,Niger,Nigeria,andEurope(returnmigrants).InSudan,theycamefromSouthSudan.10Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCross3.1Climatevariability,environmentalchange,andfutureclimatechangerisksintheSahelCommunicatingclimatechangetonon-specialistsisnotaneasytask.Thelanguageofclimatechange,includingtheuseofscientificjargonand‘bignumbers’,maynotrelatetopeople’sday-to-dayexperiences(Corneretal.,2018).Therefore,thisresearchhasframedtheinquiryintopeople’sexperienceofclimatechangeimpactsinMaliandSudanwithinabroaderperceptionofenvironmentalimpacts.PreviousresearchinbothSudanandMalishowsincreasedvariabilityofannualrainfallandtemperatures.2Furtherevidencehighlightsthenegativeeffectsofincreasinginter-annualandseasonalrainfallvariability,rainfalldistributionandconcentration;andofincreasingmeantemperaturesandchangesintemperatureextremesonvegetationcover,soildegradation,cropyields,foodinsecurity,andsoon.3Otherstudieshaveintroducednuancetothesefindings,however,showingthatenvironmentalandclimatevariabilityandtheirconsequencesarenotreducibletoanthropogenicclimatechangealone.Forinstance,astudyinSudanshowsthatforestbiodiversityisaffectedbyclimatechange-relateddrought,agriculturalexpansion,illegalwoodcutting,androadconstruction(ElTahiretal.,2010),whiledecliningsoil2Hiernauxetal.,2009;Elagib,2011;Traoreetal.,2013;Traoreetal.,2015;Halimatouetal.,2017;Hamadalneletal.,20213Hiernauxetal.,2009;SuliemanandElagib,2012;Traoreetal.,2013;Generoso,20154Holmesetal.,2022;Richardsonetal.,2022qualityislinkedtorainfallchangesaswellasagriculturalpractices(Abdietal.,2013).Similarly,researchinMalishowsthatdecliningcropyieldsmaybeattributedtochangesinrainfallwhilealsobeingdrivenbydecliningsoilqualityandfertility,orlackofneededinputssuchasfertilisers(Liehretal.,2016).Projectedclimatechangerisks.ProjectedchangesinrainfallandtemperatureintheSahelresultingfromanthropogenicclimatechange,includingincreasesinannualaveragetemperaturesandtemperature(especiallyheat)extremes,increasesinrainfallvariabilityandextremes,longerdryperiods,anddelayedrainfallonsetmayintensifycurrentclimate-relatedchallenges.4Risksincludenegativeeffectson(ibid):—agriculturalandherdinglivelihoods(e.g.decliningsoilquality,soilerosion,changesingrowingseasons,decliningcropproductionandlivestockhealth),—fisheries(e.g.threatstofishstockslinkedtochangingwaterlevelsandtemperatures),—health(e.g.changingincidencesofcommunicablediseases,healthimpactsoftemperatureextremes),and—widerthreatstobiodiversityandecosystems,alongsidemoreacutehazardssuchasflooding.Thesepresentriskstothevulnerablegroupshighlightedinthisresearchandmayexacerbateinequalitiesforfarming3.TheevidenceonclimatechangeandmigrationintheSahel11Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCross(especiallylow-intensity,low-inputrainfedfarming),herding,andfishinghouseholdsandcommunities,alonglinesofgender,age,ability,wealth,geographiclocation,andmore.Theseriskswillnotonlybeshapedbytheimpactsofprojectedclimatechangeitself,butalsobysocio-politicalfactorsindependentofclimatechange,suchasfuturepoliciesonresource(e.g.land,water)appropriationandfragmentation.Thesedifferencesarehighlightedthroughoutthereport.3.2CopingandadaptationstrategiesintheSahelCopingandadaptationstrategiesExistingstudiesprovideinsightsintopeople’scopingandadaptationstrategiesinresponsetoclimatevariabilityandchangeintheSahel,andtheirimplicationsfordisplacementandmigration.Recentresearch,includingstudiesinMaliandSudan,reportsthatthediversificationofagriculturalandnon-agriculturalincomesources,modificationstoagriculturalpractices(e.g.cropdiversification,croprotation,changestoplantingdates,multipleplantings,useofinputssuchas5Ebietal.,2011;Afifietal.,2012;Brockhausetal.,2013;Traoreetal.,2015;Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016;DeLonguevilleetal.,2019;YoungandIsmail,2019;Defranceetal.,2020;DeDialloetal.,2020;DeLonguevilleetal.,2020;Etanaetal.,20206DjoudiandBrockhaus,2011;Afifietal.,2012;Ickowiczetal.,2012;Djoudietal.,2013;Opondo,2013;BonnetandGuibert,2014;Bello,2016;Koutouetal.,2016;Epuleetal.,2017;MaregaandMering,2018;HermansandGarbe,2019;Etanaetal.,2020;Grothetal.,2020;Zoma-Traoréetal.,2020)7Brockhausetal.,2013;Sauvain-Dugerdil,2013;Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016),Sudan(Ibnouf,2011;YoungandIsmail,2019),andthewiderSahel(Djoudietal.,2013;DjoudiandBrockhaus,2011;DreesandLiehr,2015;DeubelandBoyer2017fertiliser),waterconservationandsmall-scaleirrigation,andchangesinlivestockspeciescanreduceorotherwiseaffectmigrationpressures.5Forexample,astudyinMalishowsthatwhiledroughtisassociatedwithincreasingmigrationfromruraltourbanareas,mobilityislowerwherecropsaremorediversified,andisaffectedbyhowwellhouseholdsareabletoadapttoclimate-relatedconstraints(Defranceetal.,2020).Thisreflectsadaptationstrategiesusedmorewidelyacrosstheregioninresponsetoenvironmentalandclimate-relatedchanges,alongsidetheincreasinginvolvementofherdersinagriculturalactivitiesandchangesinseasonalmobilitypatterns.6ExistingresearchinMali7alsoidentifiesmigrationasanimportantcopingandadaptationstrategy,enablinghouseholdstodiversifytheirincomesourcesbyaccessingnewresources,markets,orlabourorincomeopportunities.Inresponsetoenvironmentalchange,‘migrationservesasacopingstrategyoranimmediatereactiontobadconditionsandasanadaptationstrategyforincomediversificationinthelongrun’(Liehretal.,2016:155).However,previousresearchinMalisuggeststhatmigrationremainsadifficultchoiceinresponsetoenvironmental12Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrosschange,perceivedbypeoplewhomoveasa‘necessarybutundesirable’formofadaptationduetotheresultinginstabilityandlossofsocialnetworks(Brockhausetal.,2013).ExistingresearchpointstothecomplementarityofmigrationandadaptationintheSahel.Ontheonehand,someadaptationstrategiesmayenablepeopletoaccumulatethefinancialresourcesneededtomove,asshowninstudiesonresponsestoclimate-relatedchangesinEthiopia(Etanaetal.,2020;Grothetal.,2020).Ontheotherhand,researchinWestAfrica(Mali,Mauritania,andSenegal)andEastAfrica(Kenya)highlightstheimportanceoftransnationalmigrantnetworksascontributorsaftermovingtoadaptationintheirlocalitiesoforigin.Thismayinvolvethetransferofknowledge,technology,remittances,andotherresourcesfrommigrantstotheircommunitiesoforigin,aswellassupporttoinitiativessuchaswatersupplyinfrastructure,electrification,transportandhealthservices,andmore(Scheffranetal.,2012).Studiesshowthatmigrantremittancescanstrengthenhouseholds’abilitytocopewithhazards,povertyandfoodinsecurity,andtheircapacitytomediatelivelihoodrisks,includingthroughinvestmentsinagriculturalandherdinglivelihoods.88Gubertetal.,2010;Brockhausetal.,2013;Generoso,2015;Ng’ang’aetal.,20169DjoudiandBrockhaus,2011;Ebietal.,2011;Ibnouf,2011;Brockhausetal.,2013;Djoudietal.,2013;Dokaetal.,2014;Alouetal.,2015;Traoreetal.,2015;DeubelandBoyer2017;Dialloetal.,2020BarrierstoadaptationResearchonresponsestoenvironmentalandclimate-relatedchangeintheSahelshowsthatcopingandadaptationstrategiesarenotequallyaccessibletoall.InMaliandSudanandthewiderSahel,possibilitiesforadoptingthesestrategiesareaffectedbyexistingpatternsofinequalityofaccesstoresourcessuchaslandandwater,financialresources(e.g.financialassistance,accesstocredit),technicalassistanceandtraining,marketopportunities,anddecision-makingpowerathouseholdandcommunitylevels,alonglinesofgender,age,ethnicity,andsoon.9AshighlightedinresearchinSudan,adaptationoptionsarealsoaffectedbybroadergovernancepracticesincludingchangestolandtenuresystems,whichmaylimittheadoptionof‘traditional’adaptationstrategies(e.g.regularchangestocultivationareas)(YoungandIsmail,2019).Insomeareas,adaptationmaybecomeincreasinglydifficultduetofutureclimatetrends.AnalysisoffutureclimateprojectionsfortheSahelandassociatedsocioeconomicriskssuggeststhatinsomepartsoftheregion,futureclimate-relatedchangeshavethepotentialtoexceedadaptationlimitsduringsomeperiodsoftheyear.Forexample,thecombinationofincreasesintemperatureandhumidityextremesmayperiodicallyexceedphysiologicallimitsforhumansandlivestock,presentingathreattohealthandsurvivalandinturndisruptingandlimitingcertainsocioeconomicactivitiesaswellas13Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrosspossibilitiesforadaptation(Holmesetal.,2022;Richardsonetal.,2022).Furthermore,someadaptationstrategiescanthemselveshaveadverseenvironmentalconsequencesbyincreasingpressureonwater,land,andforestresources–then,inturn,intersectingwiththeeffectsofclimatechangetointensifymigrationpressures.Forinstance,agriculturalexpansion,irrigationdevelopment,and‘diversified’non-agriculturaleconomicactivitiessuchasminingcancreateadditionaldemandforwater,especiallyincontextsofunpredictablerainfall(seeHolmesetal.,2022).Large-scaleresponsestoclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchange–suchasthe‘GreatGreenWall’initiativeinvolvingtherestorationof100millionhectaresof‘degraded’landacross11Saheliancountriesby2030throughreforestation,vegetationregeneration,andwaterharvestingmeasures(UNCCD,2020)–willalsolikelyincreasepressureonwaterresources.3.3RelationshipsbetweenclimatechangeandmigrationintheSahelExistingmobilitypatternsintheSahelAcrosstheSahel,includinginMaliandSudan,migrationhaslongbeenanadaptationstrategyinthefaceofclimatevariabilityandenvironmentalchangeaswellaschangesinlivelihoodandeconomicopportunities10ThesefiguresarefromtheUNDepartmentofEconomicandSocialAffairs,whichincludeonlypeopleofficiallyrecordedasmigrantsandnotthosewhomoveinformallyacrossborders,andwhicharebasedondatathatmayvaryinqualityacrosscountries.Theymaynot,then,befullyrepresentativeofcurrentmigrationtrendsintheSahel.(Ouallet,2008;Barros,2010;Generoso,2015;Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016;YoungandIsmail,2019).MostmigrationintheSaheloccurswithintheregion(BluettandDavy,2020),andislargelymotivatedbyeconomicaims(Eizenga,2019)aswellasbyviolentconflict,asdiscussedbelow.Inrecentyears,socioeconomictransformation(includingchangesinagriculturalsystems),foodcrises,andwidespreadinsecurityhavecontributedtopatternsofmigrationfromruralareastourbancentresintheregion(OECD/SWAC,2014,2020).In2020,therewereroughly486,000internationalmigrantsrecordedinMaliand1.4millioninSudan.Refugeesaccountedforabout71%ofinternationalmigrantsinSudanbutonly10%ofthoseinMali.Therewere1.3millioninternationalemigrantsfromMaliand2.1millionfromSudanin2020(IOM,2022b).10Thesefigureshaveincreasedmarkedlyinrecentdecades.In2020roughly7,400peoplewerenewlydisplacedinternallybydisasters(suchasfloods,storms,extremetemperatures,anddroughts)and277,000byconflictandviolenceinMali,while454,000peopleweredisplacedbydisasters(especiallyfloods)and79,000byconflictandviolenceinSudan(IDMC,2021).Climate-migrationrelationshipsTherelationshipsbetweenclimatechangeandhumanmobilityarecomplex.Amultitudeofcontextualfactorsshapeindividuals’14Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrosschoiceandabilitytomove,leadingtooverlappingcontinuumsrangingfromforceddisplacementtovoluntarymigration,andfromtemporarymovementtoprotracteddisplacementorlong-termmigration(Opitz-Stapletonetal.,2017).Existingreviewsoftheevidenceonclimatechangeandmigrationhighlightthecomplex,context-specificnatureoftheserelationships.11Arecentevidencereviewfound‘noevidencethathuman-inducedclimatechangeiscurrentlycausingorcontributingtomigrationinauni-causal,directorunmediatedway’,andexistingstudiesconsistentlyemphasisethemulti-causalnatureofclimate-relatedmigrationandtheinfluenceofintersectingeconomic,political,social,andenvironmentalorclimate-relatedfactors(SelbyandDaoust,2021:66).Dependingonthecontext,extremeclimate-relatedeventsmaybeassociatedwithincreasedordecreasedmobility,withinandacrossnationalborders(ibid).Anotherrecentreviewshowsthatrelationshipsbetweenclimatechange,environmentaldegradation,conflictandmigrationarecontextdependent,indicatingthatthereisnosimpledirectcauseandeffect(Petersetal.,2020).Indeed,‘seekingtoisolateenvironmentalfactorsfromthecomplexinterplayofecological,economic,socialandpoliticalfactorsthat[drive]migrationdecisionswouldbeclosetoimpossible’(Hummel,2016:220).11seee.g.Borderonetal.,2019;Hoffmannetal.,2020;SelbyandDaoust,2021;Zickgraf,2021;Piguet,202212Nawrotzkietal.,2016;NawrotzkiandBakhtsiyarava,2017;Grotheetal.,2020),anddrought(Defranceetal.,2020;GrayandMueller,2012;HermansandGarbe,201913GrayandWise,2016;Nawrotzkietal.,2016;NawrotzkiandBakhtsiyarava,2017;Muelleretal.,2020a,2020bExistingevidenceonclimatechangeandmigrationintheSahelandwiderWestandEastAfricaregionshighlightsthesecomplexpatterns.Previousstudiespointtomixedfindings:thatclimate-relatedhazardsmayincreaseordecreasemobility,dependingonthetypeofshockandtheparticularcontext.NumerousstudiesintheSahelandneighbouringregionsreportthatheatextremes(Dillonetal.,2011),rainfallextremes12areassociatedwithincreasedinternalandcross-bordermigration–especiallyinareasmorereliantonagriculture,becauseofimpactsonagriculturalproductivityandincomes.InMali,astudyofyoungpeopleinKayesfoundthatreasonsformigrationincludedseekingnewopportunitiesinthefaceofinadequateanduncertainagriculturallivelihoods(Daum,2014).However,otherstudiesreportthattemperatureandrainfallfluctuationsareassociatedwithdecreasedinternalandinternationalmigration,likelybecausenegativeimpactsonagriculturalincomeimpedetheabilitytomove.13AstudyofBurkinaFasoshowsthattemperatureextremes(e.g.heatwaves)maydepletehouseholdresourcesandthusreducemigrationoptions,whilechangestorainfall(e.g.lower-than-averagerainfall,ordelayedonsetoftherainyseason)maybelinkedtoincreasedinternal,short-termmigrationbutlowerinternational,long-termmigration15Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCross(DeLonguevilleetal.,2019).Inothercases,decreasedmigrationmaybeduetoincreasedlocalworkopportunities(e.g.inagriculture)associatedwithprecipitationincreases(Muelleretal.,2020a).Stillotherstudieshavefoundthatclimatefluctuationsanddroughthaveinsignificantorinconsistenteffectsonmigration(GrayandWise,2016;Graceetal.,2018;OwainandMaslin,2018).AstudyofWestAfricancountriesfoundthatdroughtsweresignificantlyassociatedwithhighermigrationintentionsinSenegalandNiger,butnotinMauritania,Mali,orBurkinaFaso(Bertolietal.,2020),pointingtothevariabilityinclimate-migrationrelationshipsacrosscountriesintheregion.Climateprojectionssuggestthatmobilitypatternsmaychangeinthefuture–butthatthechangesarealsolikelytovaryinasimilarway.AnalysisoffutureclimateprojectionsfortheSahel,andassociatedsocioeconomicrisks,suggeststhatenvironmentalchanges(includingincreasesinannualtemperature;inheatextremes;inannualprecipitation;inrainfallvariabilityandextremerainfallevents;orinnumberofconsecutivedrydays)mayleadtochangesinexistingmobilitypatterns,especiallyamongherdingcommunities(Holmesetal.,2022;Richardsonetal.,2022).Whileclimate-relatedenvironmentalchangespresentarangeofrisksthatcontributetopressurestomigrate,theymayalsopresentneworexpandedopportunitiesthatcouldactas‘pullfactors’forin-migration.Forexample,projectedincreasesinannualprecipitationintheSahelmaycontributetoincreasedagriculturalproductivityand14Afifietal.,2012;Opondo,2013;Sauvain-Dugerdil,2013;GrayandWise,2016;Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016;DeLonguevilleetal.,2019;HermansandGarbe,2019;Bertolietal.,2020;Muelleretal.,2020bassociatedeconomicopportunities,suchasneworexpandedagriculturalopportunities,andinturnmayaffectpatternsofmigration,althoughthereisnoclearexistingevidenceonthesedynamics(SelbyandDaoust,2021;Holmesetal.,2022).Furthermore,initsSixthAssessmentReporttheIntergovernmentalPanelonClimateChange(IPCC)highlightsvulnerabilitiesgeneratedbyclimatechange(e.g.extremeweatherandclimateevents)throughdisplacementandmigration,butconcludesthat‘migrationpatterns,intheneartermwillbedrivenbysocio-economicconditionsandgovernancemorethanbyclimatechange’(IPCC,2022:15).Climate-relatedmigrationpatternsExistingevidencesuggeststhatmostclimate-relatedmigrationintheSahelisinternalandshort-term.RecentstudiesacrosstheSahel,inWestandEastAfrica,havefoundthatmigrationinresponsetoclimate-relatedandbroaderenvironmentalchangeismainlyinternalandtemporaryorshort-term(ratherthancross-borderorpermanent),potentiallybuildingonhistoriesofseasonalmigrationintheregion.14StudiesinMalireportthatmigrationinresponsetoenvironmentalchangesismainlyinternal,oftentowardlargerurbanareassuchasBamako–althoughsomemigrationdoesoccurtowardotherregionalcapitals(Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016).ClimateriskanalysesoftheSahelandEastAfricasuggestthatpatternsofpopulationmobility–includingpatternsofrapidurbanexpansionamplifiedbyrural-to-urbanmigration–mayincreaserisks16Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossrelatedtopoorhousing,sanitation,andbasicservices,especiallyininformalurbansettlements(Holmesetal.,2022;Richardsonetal.,2022).ResearchinKenya,however,hasfoundthatmostmigrationinresponsetofloodingandrainfallvariabilityoccursbetweenruralareas(Opondo,2013).Migrationchoicesanddestinationsareofteninfluencedbysocialnetworks.PreviousresearchinMalishowsthatinresponsetoenvironmentalchanges,migrationdestinationchoicesareinfluencedbythepresenceofrelativesandfriends,whocanprovideinformationonmigrationroutes,assistancewithfindingaccommodationandwork,andemotionalsupport.153.4DimensionsofclimatevulnerabilityandconnectionstomigrationpressuresandbarriersClimate-relatedvulnerabilitiesClimate-relatedvulnerabilitiesareunderstoodasvulnerabilitiestotheadverseimpactsofclimate-related(andwiderenvironmental)hazardsandchangesandtothemigrationpressuresorimmobilitythatresult.Currentevidenceprovidesinsightsintothecontextual,sociocultural,andeconomicdimensionsofvulnerabilityandmobilityintheSahel.Arisk-informedapproachhighlightsthecomplexityoftherelationshipsbetweenclimatechangeandhumanmobility,acknowledgingthe15Streiff-FénartandPoutignat,2014;Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016;BleckandLodermeier,202016Dillonetal.,2011;DjoudiandBrockhaus,2011;Ibnouf,2011;GrayandMueller,2012;Djoudietal.,2013;DreesandLiehr,2015;GrayandWise,2016;Hummel,2016;DeubelandBoyer2017;Muelleretal.,2020amultitudeofindividualandcontextualfactorsthatshapeindividuals’choiceandabilitytomove(Opitz-Stapletonetal.,2017).Itisimportanttoaccountforthesemultiplesourcesofvulnerability,whichoverlapandwhichmaydrivedifferentiatedclimatechangerisks.Intersectingformsofvulnerabilityandcapacitydeterminepeople’soptionstomoveorstayinresponsetoclimate-relatedhazardsandchanges,whichmayinturnbothincreasepressurestomovewhilealsoreducingthecapacitytodoso.Responsestorisksassociatedwithclimate-relatedmobilityshouldthereforeconsidernotonlythosewhomove,butalsothosewhocannotmoveduetosocioeconomicorotherbarrierstomobility–especiallyforpopulations‘trapped’insituationsofextremevulnerability.GenderGendercontributestoclimate-relatedvulnerabilitiesbyshapingaccesstoresources,economicpossibilities,andoptionsformobility.StudiesinSaheliancountriesreportthatmenaremorelikelytomoveinresponsetoshort-termtemperatureandrainfallfluctuationsanddroughtwhilewomenaremorelikelytobe‘trapped’,andthatmigrationcanincreasewomen’sphysicalandsocialvulnerability.16Forexample,studiesinMalishowthatmenaremorelikelythanwomentomigrateinresponsetolandandagriculturalchanges,duetosocioculturalrestrictionsonwomen’smobility(Brockhausetal.,2013;Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016).17Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossHowever,otherresearchinMalisuggestsamorecomplexpicture,showingthatinsomecommunities,womenmaybemorelikelytomoveduetomoreentrenchedpatternsofmigrationamongmenorgreaterhouseholdrelianceonmen’sincomeandthusmoreflexibilityinwomen’smovement(Graceetal.,2018).Genderalsoshapesmigrationmotivationsandduration.StudiesofresponsestoenvironmentalchangesinMalifindthatmenaremorelikelytoidentifyeconomicoreducationalmotivationsformigration,whilewomenaremorelikelytoidentifyfamily-related(e.g.marital)reasons(Konaté,2010;Sauvain-Dugerdil,2013;Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016).However,inrecentdecadeseconomicreasonshaveincreasedandfamilyreasonsdecreasedinimportanceamongwomenmigrants(Hummel,2016).Whilemenaremorelikelytoengageinseasonalmigration,womenaremorelikelytomigrateforlongerdurationsorpermanently(Liehretal.,2016).Differencesinmigrationpatternsexistamongwomenaswell.AstudyinKayesfoundthatyoungerwomenaremorelikelytomigratethanolderwomen,andthatmigrationismorecommonamongwomenwithatleastprimaryeducation(Konaté,2010).AgeExistingevidencepointstothemixedeffectsofageonexperiencesofclimate-relatedmobilityintheSahel.Agecanpresentvulnerabilitiesduetodifferentialaccesstoeconomicopportunitiesaswellasphysicalcapacitiesformigration.Studiesshowthatyoungerpeoplearemostlikelytomigrateinresponsetoshort-termclimaticfluctuationssuchastemperatureextremes(Graceetal.,2018;Grothetal.,2020;Muelleretal.,2020a).ResearchinBurkinaFasohasfoundthatolderpeoplearemorelikelytoengageinlong-termmigrationtoruralareasinresponsetopoorrainfallconditions.However,thesamestudyfoundthattheywerelesslikelytoengageinlong-termmigrationtourbanareasorinternationallyduetotheperceivedrisksassociatedwiththeseformsofmovement(DeLonguevilleetal.,2019),EmploymentandincomeRecentstudiesshowthatpeople’sdifferingmotivationsandpatternsofmovement(intermsofdurationanddestinationofmigration)candependonwhethertheirworkismoreorless‘climatesensitive’.WidespreadrelianceonagriculturalactivitiesintheSahel,includingsubsistenceandsmall-scalefarmingandherding(assourcesofincomeandfoodsupply),mayincreasepeople’svulnerabilitytoenvironmentalchangesandchangesintemperatureandrainfall.In2019,agriculture(includingfarming,herding,forestry,andfishing)accountedfor62%oftotalemploymentinMaliand38%oftotalemploymentinSudan(WorldBank,2021).Impactsalsovarywithdifferentlevelsofincome–withtheimpactsofclimatechangepotentiallymoresevereforthosewithlowerincomeandassets(whomayhaveaccesstofewerprotectiveoradaptativeresources).Somestudiesshowthatpeoplefrompoorerorlandlesshouseholdsaremorelikelytomigrateinresponsetodroughtandrainfallfluctuations(GrayandMueller,2012;Morrissey,2013),althoughotherresearchhasfoundthatwealthierhouseholdsaremorelikelytohavemigrantmembers(Etanaetal.,2020).AstudyofdisplacedcommunitiesintheEastandHornofAfricaregionfoundthatwhilepermanentrelocationinresponsetoclimaticvariabilitywasrare,thepoorestpeopleweremorelikelytorelocate(thoughinternally)(Afifietal.,2012).Morebroadly,18Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrosspreviousresearchinMaliidentifieseconomicfactors(e.g.seekingbetteremploymentandincomeopportunities)asthedominantmotivationsforinternalandinternationalmigration.17EducationClimate-relatedchangescontributetodifferentmotivationsandpatternsofmobilityamongpeoplewithdifferentlevelsofformaleducation.Individualswithnooronlyprimaryeducationmaybemorelikelytodependonclimate-sensitiveworkandarethusmorelikelytofacemigrationpressuresinthefaceofenvironmentalchanges(vanderLandandHummel,2013).However,theymayalsobelesslikelytohaveaccesstotheresourcesneededtofacilitatemobility.Forexample,astudyinKenyareportsthatpeoplewithatleastprimary-levelformaleducationaremorelikelythanthosewithoutformaleducationtomigrateinresponsetoclimatefluctuations(Muelleretal.,2020a).AstudyinBurkinaFasoshowsthatpeoplewithhigherformaleducationaremorelikelytoengageinlong-terminternationalmigrationinresponsetorainfallchanges(DeLonguevilleetal.,2019).OtherresearchinMaliandSenegalfoundthateducationallevelandeconomicactivitydonothaveasignificantinfluenceonmigrationinresponsetoenvironmentalchanges,althoughmigrationmotivationsmaydifferbyeducationlevel(vanderLandandHummel,2013;Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016).StudiesinMalishowthatpeoplewithnooronlyprimary-levelformaleducationaremorelikelythanthosewithhighereducationtoidentifyjobopportunitiesandincomeas17Sauvain-Dugerdil,2013;Daum,2014;Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016;KirwinandAnderson,2018;Hoogeveenetal.,2019;BleckandLodermeier,2020theirmainreasonsformigrationinresponsetoenvironmentalchanges,whilethosewithatleastsecondaryeducationaremorelikelytomigrateforfurthereducationortraining(vanderLandandHummel,2013;Hummel,2016).ConflictandinsecurityAcrosstheSahel,conflictcreatesconditionsofvulnerabilitythatmayintensifytheimpactsofsubsequentclimate-relatedchangesonpeople’slivelihoods,contributetomigrationpressuresandbarriers,andcompoundexistinghumanitarianneeds(describedinSection3.5).Conflict-drivendisplacementandsettlementincamps,damagetoordestructionofinfrastructure,foodinsecurity,livelihooddisruption,andlossofresourcesandpropertyintensifytheformsofvulnerabilitydescribedaboveandreducepeople’scapacitiestocopewithandadapttoclimate-relatedhazards(Naessetal.,2022).Furthermore,ongoingarmedconflictandinsecurityintheregion,aswellasgovernmentrestrictionsonmovementandborderclosuresinresponsetoarmedactivity,havedisruptedagriculturalandlivestockproductionandtrade,andinturnaffectedcropyields,income,foodprices,andfoodsecurity(FAO,2019).InMali,forexample,ongoingconflictsince2012hasmeantthatpastoralistmigrationandagriculturalproduction,aswellasaccesstomarketsforsellinggoods,havebecomemoredangerous(especiallyforwomen)duetotheoperationsofarmedgroupsandmilitaryforces,impedingthelivelihoodsofthosealreadyvulnerabletoclimate-related19Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrosschanges(TarifandGrand,2021).InSudan,agriculturalandpastorallivelihoodsystemshavebeendisruptedbyongoingintersectinglocal,national,andcross-borderconflicts(localisedinter-groupconflicts,conflictsinDarfurbetweengovernment-supportedforcesandotherarmedgroups,andcross-bordereffectsofconflictinChad)(YoungandIsmail,2019),reducingpeople’scapacitiesforcopingwithandadaptingtosubsequentenvironmentalandclimate-relatedchanges.Finally,armedconflictscaninhibitgovernmentandNGOresponsestotheadverseeffectsofclimatechange,bydivertingresourcestosecurityorconflict-relatedcrisisresponse,aswellasimpedingaccesstoaffectedcommunities.GiventhescaleofongoingconflictsacrosstheSahel–inMaliandthewiderCentralSahel,inSudan,inEthiopia,andmore–andresultingdisplacement,theimpactsofconflictonclimate-relatedvulnerabilitiesmustbeconsidered.3.5HumanitarianneedsamongmigrantsStudiesofinternalandcross-bordermigrantexperiencesintheSahelidentifyarangeofoverlappingrisks,needs,andvulnerabilities.Asinotherworldregions,people‘onthemove’intheSahelfacenumerouschallenges,includinglegalandsocietalbarrierstoaccessingbasicservices(e.g.healthcare,education)andsafehousing;legalandsocietalbarrierstoaccessingemployment(e.g.difficultiesaccessingworkpermits,discrimination);poorworkingconditions;increasedmentalhealthandpsychosocialsupportneeds;andexposurePhoto©IFRC/BritishRedCrossTheSudaneseRedCrescentSocietyrespondedtofloodingwithfirstaidandpsychosocialsupport,distributedfoodandemergencyitemsandassistedfamiliestomovetohigherground.20Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrosstogendered,sexualised,andotherformsofviolence,exploitation,andabuse(BluettandDavy,2020;Andersonetal.,2021;IhringandMeskers,2021;OHCHR,2021).Manyofthesechallenges,includinggapsinresponses,arealsosharedbymarginalisedmembersofhostcommunities.Aswellaspresentingchallengesinthemselves,theserisksandneedsfacedbymigrantscanalsointensifytheirvulnerabilitytotheimpactsofenvironmentalandclimatechange.Forinstance,barrierstohealthcareandlackofaccesstosafehousingcanrendermigrantsmorevulnerabletothehealthimpactsofheatextremes,flooding,andsoon,whilebarrierstoemploymentcanmakecopingwiththesehazardsdifficultorimpossible.Supportandservicesformigrantsareofteninsufficientinresponsetotheseneedsandvulnerabilities,andarenotequallyaccessibletodifferentcategoriesofmigrants(BluettandDavy,2020).Despite‘freemovement’frameworks,migration-relatedpoliciesandpracticeswithintheSahelhavebeenshowntocontributetohumanitarianvulnerabilitiesamongmigrants,throughadministrativeandfinancialbarrierstoobtainingresidentandworkpermits,andlegalandsocietalbarrierstohealthcareandeducationservices,housing,andemployment(BluettandDavy,2020).Whilesomesupport(e.g.housing,education)maybeprovidedtorefugeesbytheUNHCR,othercategoriesofmigrantsoftendonotbenefitfromsimilarsupport(ibid).Manypeoplemaymoveacrossbordersoutsideofofficialprocesses,renderingthemparticularlyprecariousandvulnerabletoexploitation.Since2020,nationalresponsestotheCOVID-19pandemic,includingrestrictionsonmobilitywithinandacrossborders,havepresentedadditionalbarrierstomigration.Thepandemichasalsointensifiedandcreatednewrisksforpeopleonthemove,alongsidemembersofhostcommunities,includingthesecondaryimpactsofpoliciesintendedtomitigateCOVID-19transmission.Ithas,forexample,exacerbatedissuesrelatingtounsafeshelterandaccesstohealthcare,whilerestrictionsoncommercialactivitieshaveposedchallengestolivelihoods(Andersonetal.,2021;IhringandMeskers,2021).21Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCross4.1ObservedenvironmentalchangesandperceivedcausesRespondentsinMaliandSudanwereaskedtodescribeenvironmentalchangestheyhadobservedintheirhomearea(orregionoforigin)andtheseverityandlengthofthesechanges.Theseincludedsudden-onsethydro-meteorologicalhazards(suchasheat,flooding,orstorms)andchangesinweatherpatterns,aswellaslonger-termchangesrelatedtoland,water,andforests.Whilerespondentswereaskedtodescribebothnegativeandpositiveenvironmentalchanges,theobservationsweregivenprimarilyinnegativeterms,withfewerpositivechangesidentified.Virtuallyallrespondentshadobservedenvironmentalchangesintheirlocalities,withsignificanteffectsontheirsocialandeconomicconditions.InMali,91%ofrespondents(94%inBamakoand88%inKayes)reportedsuchchanges.InSudan,itwas100%oftherespondentsacrossthethreesitesofDabatBosin,ElganaaandElfao–whichcanbeexplainedbytheirrecentexperienceoffloodinganddisplacement,inadditiontoslow-onsetenvironmentalstresses.Mostoftherespondentsacrossthetwocountries(92%inSudanand91%inMali)classifiedthesechangesas‘veryserious.’RespondentsinMaliandSudandescribedmajornegativeclimate-relatedchangesasthoseaffectingthevariability,distribution,andconcentrationofrainfallandtheirassociatedsecondaryhazards,suchasfloodanddroughts(seeFigure1).DifferenceswerenoticeablebetweenMaliandSudan.InMali,respondentsreportedadrierclimatewithdecreasedrainfall(56%ofrespondents)andrainfalldelays,longerandincreaseddroughts(30%),andincreaseintemperature(30%)andtemperatureextremes.FGDparticipantsandkeyinformantsfromthegovernmentandNGOsechoedthesefindings,addingthatwinterperiodswereshortening,oftenfromfourtotwomonths.Bycontrast,Sudaneserespondentsreportedawetterclimatewithincreasedrainfall(61%)andchangesinrainfalltiming(48%),morefrequentorsevereflooding(52%),andmorefrequentandseverestorms(38%).FGDparticipantsspecifieddelayedonsetsoftherainyseason,andchangesinrainfallpatterns(longspellsduringtherainyseasonandabove-averagerainfallinsomeseasons,leadingtocropdamage).However,inWhiteNile,Sudan,54%ofrespondentsviewedincreasedrainfallpositively,asitimprovedagriculturaloutputinrainfedfarming.PerceptionsofadrierclimateinMaliareinfluencedbyhistoricaleventsandtheirconsequences.TheSaheliandroughtsinthe1970sand80shavehadprofoundandlastingeffectsonpeople’sunderstandingsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchangesintheregion(Liehretal.,2016),includingthebeliefthatrainfallhasdeclinedoverthepastdecades,eventhoughrainfallovertheSahelhasinfactrecoveredsincethe1990s(Holmesetal.,2022).InSudan,perceptionsofawetterclimatecanbeexplainedbythemakeupoftherespondentgroup:theyhadallexperienceddevastatingfloodsthatforcedthemtomove.Thisisalsosupportedbytheperceivedlengthandtimingofchangesreported,as78%ofrespondentsinSudanstatedthattheyhadhappenedwithinthelastonetothreeyears.Incomparison,overhalfofrespondentsinMali(55%)reportedobservingchangeswithinthepastfourto10years,andathirdreportedthattheyhaveoccurredformorethan10years.4.Keyfindings:perceptionsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchangeinMaliandSudan22Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossFigure1.Negativeclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchangesobservedbysurveyrespondentsin█Maliand█Sudan0102030405060708090100IncreaseinrainfallMorefrequentorseverestormsMorefrequentorseverefloodingLossofaccesstolandDecreaseintemperatureChangesintemperaturetimingIncreaseintemperatureLongerormorefrequentdroughtsSoildegradationorerosionChangesinrainfalltimingDecreaseinrainfallReduction,pollutionand/orchangesinwatersourcesDeforestation64%63%57%76%56%8%34%48%32%41%30%16%24%12%21%10%17%9%15%52%11%52%10%38%8%61%23Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossInbothcountries,thekeynegativeenvironmentalchangesidentifiedbyrespondentswerethosemoreeasilyattributabletomanmadeactivities,includingdeforestation,reductionorpollutionofwatersources,andsoildegradation(Figure1).InMali,88%ofpeopleattributedthesechangestohumanintervention,includingagriculturalpractices(69%),energydemands(61%),mining(53%),industrialactivities(49%),andherdingpractices(43%).NumerousFGDandinterviewrespondentsidentifiedtheover-cuttingoftreesforfirewoodanddesertencroachmentasthemainreasonfordeforestationandsoilerosion.Othersnotedtheoveruseofpesticidesandfertilisersinagricultureandchemicalproductsinminingascontributingtowaterpollutionanddecreasedfishspecies.Miningwasdescribedbyoneintervieweeasmoredangerousthanclimatechange.Somerespondentsalsomentionedtheseizureoflandbyelectedofficials,conflictsoverlivestockgrazinglandbetweenherdersandfarmers,andtheactionsofsecurityforcesorarmedgroupsasaffectingaccesstoland,water,andforestresourcesandcontributingtoenvironmentaldegradation.InSudan,thesmallminorityofsurveyrespondents(13%)whoattributedenvironmentalchangestomanmadeactionsreportedthattheexpansionoflarge-scalemechanisedfarming,whichnowcoversmillionsofhectaresattheexpenseofnaturalvegetationcover,wasthekeydriverofdeforestation.ThiswashighlightedinElfao,GadarifStateandElganaa,WhiteNileState.Moreover,SouthSudaneseinformantsintheDabatBosinrefugeecampreportedthatamajorissuetheyfacedbackhomebeforedisplacementwasinsecurityduetoconflictsoverlandgrazingandwaterforcattle.However,mostrespondents(nearly90%)attributedtheobservedenvironmentalchangetothewillofGod.Thedifferencesinperceptionsofthedriversofclimate-relatedandbroaderenvironmentalchange(i.e.humanvsdivineinfluences)betweenMaliandSudanmaybeexplainedbythetypesofhazardthatpeopleexperienced.InSudan,themajorityofrespondentssufferedfromrapid-onsetevents(i.e.floods)–thesetypesofeventsmaybemoreaffectedbyanthropogenicclimatechangethanthekindsofhazardsexperiencedbythoseinMali.Withoutascientificunderstandingofthelinkagesbetweengreenhousegas(GHG)emissionsandhydrometeorologicalimpacts,respondentsmayhaveresortedtoGodtorationalizethedisastersthataffectedthem.Thisinterpretationissupportedbythe13%minoritythatattributedenvironmentalchangestohumanintervention,whofocusedonenvironmentalimpactsthatcanbeeasilyattributedtomanmadeactions,includingtheimpactofagriculturalpracticesonwaterresourcesandsoilerosionandreducedaccesstolandduetolarge-scalemechanisedfarming.Thesefindingsalignwithpreviousresearchontheinteractionbetweenagriculturalandlandpolicies,livelihoodpractices,andenvironmentalchange.TheexistingliteratureonMaliandtosomeextentSudanillustratestheimpactsofagriculturalexpansion(includinglarge-scalecommercialagriculture)onenvironment,landaccess,agriculturalandherdinglivelihoods,andmobility(Lindetal.,2020;MaregaandMering,2018;Sulieman,2013;SuliemanandElagib,2012;YoungandIsmail,2019).Meanwhile,widerresearchonchangestoagriculturalandherdinglivelihoodsintheSahelhashighlightedtheimpactsofagriculturaldevelopmentandexpansion;landtenureandresources24Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossmanagementsystems;andgovernancereforms,allinteractingwiththeeffectsofclimatechangetoshapemigrationpressuresandbarriersacrosstheSahel.184.2Impactsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchangesanddifferentiatedvulnerabilitiesThemainregionaleconomicactivitiesidentifiedbyrespondentshighlightthesignificanceofagriculturalactivities,includingfarmingandherding,acrossthetwocountries(seeTable2,Section2.4).InMali,morethan90%ofrespondentsinbothBamakoandKayesidentifiedsubsistenceagricultureasthemaineconomicactivity,whilecommercialagriculturewasidentifiedbyaboutathirdofrespondents.Subsistenceherdingwasidentifiedasthemaineconomicactivitybynearly50%ofrespondentsinthetworegionsandcommercialherdingwasidentifiedbyabout40%,pointingtothesignificanceofcommerciallivestockmarketsintheregion.TradeisamorecentraleconomicactivityinBamako,whilefishingactivitiesandthetransportsectorplayagreaterroleforrespondentsinKayes.Similarly,inSudan,subsistenceagricultureisthekeyeconomicactivity(99%),togetherwithsubsistenceherding(79%)andfishing(59%).DifferingfromMali,respondentsinSudanengagedfarlessincommercialactivities–whicharegenerallymoreprofitable–exceptforalimitednumberofcommerciallivestocktraders.18Benjaminsenetal.,2010;Ickowiczetal.,2012;Bouaré-Trianneau,2013;BonnetandGuibert,2014;Doso,2014;Hiernauxetal.,2014;Kiemaetal.,2014;Daouda2015;Koutouetal.,2016;Nilssonetal.,2020;Zoma-Traoréetal.,2020RespondentsinMaliandSudanidentifieddecreasedagriculturalproductionanddecreasedherdsizesasthekeynegativeimpactsofenvironmentalchange,followedbysmallerfishcatches,foodinsecurity,andnegativeemploymentandhealthimpacts(seeFigure2).TheseimpactsweremostprominentinSudan,wherealmosteveryrespondenthadsufferedfromloweragriculturaloutputandsmallerherdsizes.Thisreducedfoodquantityandquality,andledtohigherfoodinsecurityandimpoverishment(linkedtodecliningincomeandtherisingcostsofcerealsandotherfoods),hunger,andillness–aswellashavingsubsequenteffectsonhouseholdstabilityandmigration.ThehugeincidenceoffoodinsecurityinSudan(99%ofrespondents)comparedtoMali(32%)canbeattributedtothepredominanceofsubsistenceactivitiesInMali,threequartersofrespondentsreporteddecreasedagriculturaloutputs,whereasaroundonethirdreportedexperiencingtheotherimpacts.Inaddition,FGDrespondentsinMalialsomentionedanincreaseinheat-relatedillnessesandmalaria;theemergenceofnewdiseases;theeffectsofpoorerwaterqualityonhealth;anddifficultiesaccessinghealthcareduetodecliningincomeasfurthernegativeimpactsofenvironmentalandclimate-relatedchanges.Aminority(13%)ofrespondentsinMalireportedlessseverefoodinsecurityduetoenvironmentalchange,whereasvirtuallynopositiveimpactswereperceivedbyrespondentsinSudan.25Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTwobroadcategoriesofpeopleemergefromtheresearchasbeingparticularlyclimate-vulnerable:firstly,farmers,herdersandfishers,duetotheoutsizedimpactsofclimateandenvironmentalchangeontheirlivelihoods;andsecondly,peoplewhoarevulnerabletobothclimate-relatedandnon-climate-relatedstressesandhazards,duetowidersocio-economicfactors(e.g.genderinequality,poverty,conflict)(seeFigure3).InterviewsandFGDsinBamakoandKayes,Maliemphasisedthechallengesfacingfarmers,includingthelossofcultivableland,insufficientwater(forrainfedagriculture)duetoirregularrainfall,andpoorsoilqualityresultingindecliningcropyields,aswellasheavyrainfallthatdestroyscrops–witheachofthesechallengesreducingtheirresilience.Forherders,challengescamefromthedegradationandlossofpastureland,difficultiesaccessingsufficientwaterandfoodforlivestock,andtheincreasingpricesofwater,fertilisers,equipment,andlivestockfeedasaconsequenceofenvironmentalchange.AsnotedduringafocusgroupwitholdermeninBamako,“Atthetimeof[our]parents,itwasrainingenoughandtheanimalshadgrasstograzeforalongtime,whichallowedthemtostayinshapeforwintering…Todaytheoppositeishappening.”Accordingtoonesurveyrespondent,thesechallengeswereleadingto‘massiveabandonmentofherding.’Forfishers,challengeswereassociatedwithreductionsinriverwaterlevelsand,inturn,reductioninthequantityoffishcatch,andadeclineinordisappearanceofcertainplantandanimalspecies.Othersnotedthatarmedconflicthaspreventedfarmersfromcultivatingtheirfields.Thesewidersocioeconomicandsecurityfactorsunderpinandexacerbatevulnerabilitiestoenvironmentalandclimate-relatedchanges.Elderlypeoplewereamongthoseidentifiedasthemostvulnerabletotheimpactsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchangeinbothMaliandSudan.ThiswasfarmorepronouncedinSudan(70%ofrespondents)thaninMali(22%)despitethefactthattheformerhadalowershareofrespondentsagedover55(15%)thanthelatter(55%).ThismaybeinfluencedbythefactthatmostSudaneserespondentsobservedfirst-handthehardshipsfacedbyelderlypeopleduringtheirdisplacementjourneys,shapingtheirviewofolderpeople’svulnerability.Incomparison,respondentsinKayes,Mali(whichisasendingdestinationofmigrants)wereintheirlocalityoforiginandmaynothavehadacomparableexperienceshapingtheirperceptions.InFGDsinMali,respondentsalsoindicatedpeoplewithdisabilities,especiallyamongtheelderly,asbeingparticularlyvulnerable.Thehighervulnerabilityofelderlypeopleandpeoplewithdisabilitiesisassociatedwiththeirlowertolerancetotemperatureextremesandtotheeffectsofmalnutritionasaresultofimpoverishment.Somerespondentsalsolinkedthechallengesaffectingolderpeopletotheirresponsibilitiesasheadoftheirfamilies,whichintensifythepressuresresultingfromenvironmentalchangesandnegativeeffectsonlivelihoods,incomes,andabilitytomeethouseholdneeds.Manygroupsfacingvulnerabilitiestotheimpactsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchangealsofacebarrierstocopingandadaptationstrategies,asdiscussedinSection5.2.ParticularlyinSudan,womenwereperceivedtohaveincreasedvulnerabilitytotheeffects26Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossFigure2.Effectsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchangesreportedbysurveyrespondentsin█Maliand█Sudan0102030405060708090100DecreaseinfishingcatchesNegativeemploymentimpactsNegativehealthimpactsMoreseverefoodinsecurityDecreaseinherdsizeDecreaseinagriculturalproduction74%40%38%32%34%15%77%32%25%30%23%20%DecreaseinfishingcatchesNegativeemploymentimpactsNegativehealthimpactsMoreseverefoodinsecurityDecreaseinherdsizeDecreaseinagriculturalproductionMALIBamakoKayes0102030405060708090100DecreaseinfishingcatchesNegativeemploymentimpactsNegativehealthimpactsMoreseverefoodinsecurityDecreaseinherdsizeDecreaseinagriculturalproduction74%40%38%32%34%15%77%32%25%30%23%20%DecreaseinfishingcatchesNegativeemploymentimpactsNegativehealthimpactsMoreseverefoodinsecurityDecreaseinherdsizeDecreaseinagriculturalproduction27Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCross0102030405060708090100DecreaseinfishingcatchesNegativeemploymentimpactsNegativehealthimpactsMoreseverefoodinsecurityDecreaseinherdsizeDecreaseinagriculturalproduction85%87%98%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%98%85%47%96%92%70%2%DecreaseinfishingcatchesNegativeemploymentimpactsNegativehealthimpactsMoreseverefoodinsecurityDecreaseinherdsizeDecreaseinagriculturalproductionDecreaseinfishingcatchesNegativeemploymentimpactsNegativehealthimpactsMoreseverefoodinsecurityDecreaseinherdsizeDecreaseinagriculturalproduction0102030405060708090100DecreaseinfishingcatchesNegativeemploymentimpactsNegativehealthimpactsMoreseverefoodinsecurityDecreaseinherdsizeDecreaseinagriculturalproduction85%87%98%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%98%85%47%96%92%70%2%DecreaseinfishingcatchesNegativeemploymentimpactsNegativehealthimpactsMoreseverefoodinsecurityDecreaseinherdsizeDecreaseinagriculturalproductionDecreaseinfishingcatchesNegativeemploymentimpactsNegativehealthimpactsMoreseverefoodinsecurityDecreaseinherdsizeDecreaseinagriculturalproduction0102030405060708090100DecreaseinfishingcatchesNegativeemploymentimpactsNegativehealthimpactsMoreseverefoodinsecurityDecreaseinherdsizeDecreaseinagriculturalproduction85%87%98%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%98%85%47%96%92%70%2%DecreaseinfishingcatchesNegativeemploymentimpactsNegativehealthimpactsMoreseverefoodinsecurityDecreaseinherdsizeDecreaseinagriculturalproductionDecreaseinfishingcatchesNegativeemploymentimpactsNegativehealthimpactsMoreseverefoodinsecurityDecreaseinherdsizeDecreaseinagriculturalproductionSUDANDabatBosinElganaaElfao28Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossFigure3.Groupsidentifiedasmostseverelyaffectedbyenvironmentalchangesamongsurveyrespondentsin█Maliand█Sudan(multiplechoiceanswers)27%Women58%31%Youngpeople9%22%Olderpeople70%31%Herders50%69%Farmers78%15%Fishers9%4%Othervulnerablegroups4%MALISUDAN29Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchange,duetotheirhouseholdresponsibilities.Women’sincomeinMaliandSudanishighlydependentonvegetablecultivationandtheagriculturalsector,andthustochangesinrainfallandwatersources.Inadditiontotheirmaineconomicactivity,womenwerealsoreportedasresponsibleforhouseholdwork(52%inSudan),e.g.collectingwater,whichcontributestotheirvulnerabilitytoenvironmentalimpacts.InMali,youngpeople,especiallyyoungmen,werealsoperceivedasexperiencingincreasedvulnerabilitytoenvironmentalchange,duetoalackofeconomicopportunities.Alackofemploymentandalternativeeconomicopportunitiesaddsaburdentotheresponsibilitythatyoungmenperceiveastheheadsoftheirfamilies;thiscontributestopressureforthemtomigrateandthustotheirincreasedexposureandvulnerabilitytoenvironmentalimpacts.SomeFGDrespondentsinMalinotedthatchildrenareparticularlyvulnerabletothehealthimpactsofenvironmentalchanges.ThiscontrastswithfindingsfromSudan,whereonly9%ofrespondentsconsideredyoungpeopletobemostvulnerable,thoughitisunclearwhytherewassuchdifference.Poorerhouseholdswereidentifiedtobemorevulnerable,duetotheabsenceofreserveresources.ThiswasidentifiedbyrespondentsinFGDsinMali.Thelackoflandownershipheavilycontributedtothisvulnerability,whereasreserveresourcesandlandwereseenasservingaprotectivefunctionforwealthierhouseholds.AsagroupofolderwomeninMalistated,“Thesituationoftherichandthelandownersisdifferentbecausetheywillalwayshavesomething.”Meanwhile,anothergroupofoldermenexplainedthatdifferentialvulnerabilitytotheimpactsofenvironmentalandclimate-relatedchangeisinseparablefrombroadersystemsofeconomicinequality:“Theimpactsaredifferentfortherichandthepoor,becausetherichgetricheronthebacksofthepoor.Thesamegoesforlandownersandlandlesspeople,sinceeverydaylandownerstakethegoodplots[ofland].”EthnicminoritiesinMaliwerealsoidentifiedashavingincreasedvulnerabilitytoenvironmentalchange,basedonexistingsystemsofmarginalisationandinequality.DuringFGDs,onegroupofyoungpeopleinBamakonotedthatethnicgroupsincludingtheSonrhaï,Dogons,Peulhs,andBozosfacemorenegativeeffectsofenvironmentalchange,giventhattheyfacebroaderformsofsocial,economic,andpoliticalmarginalisationthatintensifyvulnerability(intermsofprecariouslivelihoodsorbarrierstolandaccess,forexample).30Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossAsdiscussedinSection2.3,existingresearchhasdocumentedarangeofcopingandadaptationstrategieswhichpeoplehaveadoptedinresponsetoclimatevariabilityandchangeintheSahel,whichcanaffectmigrationpressures.Here,‘copingstrategies’referstopeople’sshort-termresponsestoenvironmentalchangesandchallenges,while‘adaptationstrategies’encompassesthelonger-termadjustmentspeoplemaymaketoenablethemtoremaininplaceinthecontextofsuchchangesandchallenges,aswellassupportingtheirchoicesaboutmobility.Itshouldbenoted,however,thatthestrategiesdescribedbelow,whileframedasresponsestoenvironmentalchangesandchallenges,mayalsobeadoptedinresponsestoothersocialandeconomicchallenges.5.1Strategiestocopewithclimate-relatedenvironmentalchangesandchallengesOverall,copingandadaptationstrategieswerereportedbymorerespondentsinMalithaninSudan,likelyreflectingdifferencesinthetypesofchangesandhazardstheyhadexperiencedandtheextentofadaptationneeded.InMali,respondentsdescribedlonger-termenvironmentalchanges,whichmayallowpeoplemoretimetoidentifyandimplementadaptationstrategies.InSudan,thesudden-onsetnatureofenvironmentalhazards(floods)maylimitpossibilitiesforadaptationresponses.FloodsaroundtheNileRiverinSouthSudanandSudanhavebeenincreasinglysevereanddestructivesince2019,linkedtochangesinrainfallintensity,humanimpactsonthephysicalenvironment,andthepoorplanningofsettlements(Tiitmamer,2020;Elagibetal.,2021).Inaddition,adaptationmeasuressuchasflooddefences,diversioncanalsandreservoirs,andsoonrequireresourcesbeyondthecurrentcapacityofindividualsandhouseholds(Tiitmamer,2020,2021).MigrationwasconsideredasignificantadaptationstrategyinbothMaliandSudan(seeFigure4).OverhalfofsurveyrespondentsinMaliandnearlyallsurveyrespondentsinSudan(98%)identifiedmigrationasacommonadaptationstrategyinthefaceofenvironmentalorclimate-relatedchange,asdiscussedindetailinSection6.InMaliandSudan,changesinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesandchangestoagriculturalpracticesarecommonstrategiespeopleusetoadapttoenvironmentalchangeswhilestayinginplace–reflectingthefindingsofpreviousresearch.Theseadaptationstrategieswereidentifiedbyabout60%ofsurveyrespondentsinMaliand30to40%ofrespondentsinSudan.InMali,FGDrespondentsdescribedstrategiesincludingtheadoptionofnewagriculturaltechniques(e.g.newcropvarieties,changestoplantingseasonssuchasearlyseedplanting),theconstructionofsmallvegetablegardens,lowland/wetlanddevelopment,andwaterresourceimprovement(e.g.smalldams,waterretainingstructures,newwaterpoints).RespondentsinKayesweremorelikelythanthoseinBamakotoidentifychangesinworkorsubsistenceactivitiesasadaptationstrategies,likelyreflectingdifferencesincopingstrategiesbetweenmoreruralandmoreurbansettings.InSudan,respondentsdescribedadoptingdrought-resistantandshort-maturingcropvarietiesduringdryperiods,andcropsthatcanwithstandhighersoilmoistureduringrainyandfloodyears.Herdingpractices(suchasmovementtopasture)arealsomodifiedtocopewithchangingenvironmentsandweather5.Keyfindings:copingandadaptationstrategiesinMaliandSudan31Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrosspatterns.Theseechothein-placecopingandadaptationstrategiesdescribedinpreviousresearch,summarisedinSection3.2.Strategiesforshort-termcopingwithclimate-relatedhazardsandchangesincludethecreationofwaterand/orfoodreserves,thesaleofassets,andchangesinconsumptionhabits.Saleofassets(suchaslivestock)andchangesinconsumptionhabitswereeachreportedbyaboutaquarterofsurveyrespondentsinMaliandaboutone-fifthofrespondentsinSudan.InMali,respondentsexplainedthatthesaleofassetsismostoftendoneduringperiodsoffoodinsecurity,toenablethepurchaseoffoodandmeetotherbasicneeds(e.g.children’seducation).InSudan,respondentsreportedthatthesaleofassetswasastrategytoraisemoneytomigrate.InMali,respondentsinKayesweremorelikelytoidentifythecreationofwaterorfoodreservesasadaptationstrategies,whilerespondentsinBamakoweremorelikelytoidentifychangesinconsumption,likelyreflectingdifferencesinpossiblecopingstrategiesbetweenmoreruralandmoreurbansettings.InSudan,respondentsinElfaoweremorelikelythanthoseinothersitestoreportsuchcopingstrategies,potentiallybecauseresidentsofthetwoothersitesinSudanhadbeendisplacedbyfloodingandmaythereforehavehadfeweroptionsforcopinginplace.19RepresentativesoftheRedCrossofChad,BurkinabeRedCrossSocietyandtheSenegaleseRedCrossSocietyalsoreportedthatpeopleseekingneweconomicopportunitiesinresponsetotheimpactsofenvironmentalchangesonagricultureareengaginginartisanalgoldmining,whichhasharmfulimpactsonsoilandwater,andinthesaleofcharcoal,whichiscontributingtodeforestation.Changesinhousing(locationofstructure)weremorecommonlyreportedbyrespondentsinSudan,reflectingastrategytoadapttoincreasingfloodrisks.Thiswasreportedbynearly40%ofrespondentsinSudan,comparedtojustover10%inMali.ThislikelyreflectsthemakeupofrespondentsinSudan,wheremanyhadbeendisplacedbyfloods.Someadaptationstrategiescanthemselveshaveadverseenvironmentalconsequencesduetoincreasedpressuresonland,water,andforestresources(asreflectedinexistingresearch,discussedinSection3.2).Forinstance,anintervieweeinKayesdescribedhowaprevious‘greenbelt’tree-plantinginitiativesupportedbytheGermangovernmenthadsubsequentlybeencutdownforconstructionpurposesandforsaleasfirewood.PreviousstudiesinMaliandSudanreportthatcharcoalproductioncanbeanimportantincomediversificationstrategyinresponsetoenvironmentalchangesandclimatevariability,especiallyforwomen(Brockhausetal.,2013;YoungandIsmail,2019)–butcanalsocontributeincreasedpressuresonforestresourcesandworsentheriskofdeforestation.Similarly,alternativeeconomicopportunitiessuchasartisanalgoldmining,describedbyrespondentsinSudan,canhaveveryharmfulimpactsonlocalenvironments,includingthepollutionofwatersources,soilerosion,andmore(seeHolmesetal.,2022).1932Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossFigure4.Copingandadaptationstrategiesidentifiedbysurveyparticipantsin█Maliand█Sudan(overleaf)0102030405060708090100Changeinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesChangesincroptypesand/oragriculturalpracticesMigrationoffamilymembersCreationofwaterand/orfoodreservesChangesinherdingpracticesSaleofassets(e.g.livestock)ChangesinconsumptionhabitsChangesinfishingactivitiesChangesinhousinglocationorstructureChangeinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesChangesincroptypesand/oragriculturalpracticesMigrationoffamilymembersCreationofwaterand/orfoodreservesChangesinherdingpracticesSaleofassets(e.g.livestock)ChangesinconsumptionhabitsChangesinfishingactivitiesChangesinhousinglocationorstructure50%58%70%30%32%26%32%14%4%70%62%34%48%28%26%16%22%18%MALIBamakoKayes0102030405060708090100Changeinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesChangesincroptypesand/oragriculturalpracticesMigrationoffamilymembersCreationofwaterand/orfoodreservesChangesinherdingpracticesSaleofassets(e.g.livestock)ChangesinconsumptionhabitsChangesinfishingactivitiesChangesinhousinglocationorstructureChangeinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesChangesincroptypesand/oragriculturalpracticesMigrationoffamilymembersCreationofwaterand/orfoodreservesChangesinherdingpracticesSaleofassets(e.g.livestock)ChangesinconsumptionhabitsChangesinfishingactivitiesChangesinhousinglocationorstructure50%58%70%30%32%26%32%14%4%70%62%34%48%28%26%16%22%18%33Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCross0102030405060708090100Changeinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesChangesincroptypesand/oragriculturalpracticesMigrationoffamilymembersCreationofwaterand/orfoodreservesChangesinherdingpracticesSaleofassets(e.g.livestock)ChangesinconsumptionhabitsChangesinfishingactivitiesChangesinhousinglocationorstructureChangeinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesChangesincroptypesand/oragriculturalpracticesMigrationoffamilymembersCreationofwaterand/orfoodreservesChangesinherdingpracticesSaleofassets(e.g.livestock)ChangesinconsumptionhabitsChangesinfishingactivitiesChangesinhousinglocationorstructureChangeinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesChangesincroptypesand/oragriculturalpracticesMigrationoffamilymembersCreationofwaterand/orfoodreservesChangesinherdingpracticesSaleofassets(e.g.livestock)ChangesinconsumptionhabitsChangesinfishingactivitiesChangesinhousinglocationorstructure24%0%2%2%2%0%100%13%5%5%38%38%33%52%100%22%30%30%32%27%76%94%10%10%44%0%48%SUDANDabatBosinElganaaElfao0102030405060708090100Changeinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesChangesincroptypesand/oragriculturalpracticesMigrationoffamilymembersCreationofwaterand/orfoodreservesChangesinherdingpracticesSaleofassets(e.g.livestock)ChangesinconsumptionhabitsChangesinfishingactivitiesChangesinhousinglocationorstructureChangeinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesChangesincroptypesand/oragriculturalpracticesMigrationoffamilymembersCreationofwaterand/orfoodreservesChangesinherdingpracticesSaleofassets(e.g.livestock)ChangesinconsumptionhabitsChangesinfishingactivitiesChangesinhousinglocationorstructureChangeinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesChangesincroptypesand/oragriculturalpracticesMigrationoffamilymembersCreationofwaterand/orfoodreservesChangesinherdingpracticesSaleofassets(e.g.livestock)ChangesinconsumptionhabitsChangesinfishingactivitiesChangesinhousinglocationorstructure24%0%2%2%2%0%100%13%5%5%38%38%33%52%100%22%30%30%32%27%76%94%10%10%44%0%48%0102030405060708090100Changeinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesChangesincroptypesand/oragriculturalpracticesMigrationoffamilymembersCreationofwaterand/orfoodreservesChangesinherdingpracticesSaleofassets(e.g.livestock)ChangesinconsumptionhabitsChangesinfishingactivitiesChangesinhousinglocationorstructureChangeinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesChangesincroptypesand/oragriculturalpracticesMigrationoffamilymembersCreationofwaterand/orfoodreservesChangesinherdingpracticesSaleofassets(e.g.livestock)ChangesinconsumptionhabitsChangesinfishingactivitiesChangesinhousinglocationorstructureChangeinworkand/orsubsistenceactivitiesChangesincroptypesand/oragriculturalpracticesMigrationoffamilymembersCreationofwaterand/orfoodreservesChangesinherdingpracticesSaleofassets(e.g.livestock)ChangesinconsumptionhabitsChangesinfishingactivitiesChangesinhousinglocationorstructure24%0%2%2%2%0%100%13%5%5%38%38%33%52%100%22%30%30%32%27%76%94%10%10%44%0%48%34Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCross5.2BarrierstocopingandadaptationInMaliandSudan,alackoffinancialresourceswasthemostcommonlyreportedbarriertotheadoptionofcopingandadaptationstrategiesinresponsetoenvironmentalchanges.Thiswasidentifiedasamainbarrierby85%ofsurveyrespondentsinMaliand97%ofthoseinSudan,andfiguresweresimilaracrosssurveylocationswithinbothcountries.Thismaybeconnectedtotheimpactsofenvironmentalchangesonlivelihoods.Decreasedagriculturalproductionandherdsizes,smallerfishcatches,andnegativeemploymentimpacts(describedinSection4.2)leadtolowerincome,andmeanthatfewerresourcesareavailableforcopingandadaptationmeasures.Furthermore,asdiscussedinSection4.2,poorerhouseholdshavefewerreserveresourcesavailabletosupportadaptation.FGDrespondentsinMaliexplainedthatfinancialbarrierswereinpartaresultofinsufficientsupportfromgovernmentandinternationalpartners,discussedingreaterdetailinSection5.3.DifferencesbetweenMaliandSudaninresponsesrelatingtootherbarrierstocopingandadaptationstrategiesmaybeexplainedbythetypesofenvironmentalhazardsthatpeopleexperience.InMali,alackoftraining(61%)andinformationoncopingandadaptationstrategies(43%)wasfrequentlyidentifiedasanobstacle.Incontrast,thesebarrierswereidentifiedbyonly5%and25%,respectively,ofsurveyrespondentsinSudan.Thismaybeduetothenatureandseverityoftheenvironmentalhazards(floods)underpinningdisplacementinSudan,wherecopingandadaptationareunderminedbyfactorsotherthaninsufficientknowledge.InMali,respondentsinKayesweremorelikelythanrespondentsinBamakotoreportfinancial,training,andinformationalbarrierstoin-placecopingandadaptation.Thismayreflectpeople’sengagementwithdifferentadaptationoptionsinurbansettings(e.g.wagedemployment,ratherthanadaptationstoagriculturalpractices).Thepresenceofarmedgroupsandongoinginsecurityalsoimpedestheimplementationofadaptationresponses.WhilethiswasreportedmainlybyrespondentsinMali,thewaysinwhichconflictandinsecuritycanintensifyvulnerabilitiestoenvironmentalandclimate-relatedchanges,whilelimitingoptionsforin-placecopingandadaptation,isanimportantconsiderationacrossthewiderSahel.InMaliandSudan,womenwereidentifiedasfacingthegreatestbarrierstocopingandadaptation,dueinparttoobstaclesinaccessingfinancialsupport.Thiswasreportedbysimilarproportionsofsurveyrespondentsinbothcountries(41%inMaliand36%inSudan).InMali,respondentsexplainedthatthisisdueinparttogenderedinequalitiesinaccesstofinancialsupport(e.g.credit,loans)frombanksandothersources.Barriersfacingwomenincludediscriminatorysocialnorms,limitedfinancialliteracy,andlimitedlandrights(whichinturnlimitcollateralforloansorcredit)(Bizoza,2019).However,manysurveyrespondentsalsodescribedwomen’smobilisationofsharedresources(e.g.‘tontines’–sharedsavingcirclesamongpeers)tocopewiththeeffectsofenvironmentalchanges,highlightingtheneedtoconsiderbothgenderedvulnerabilityandagencyinresponsestoenvironmentalandclimate-relatedchange.RespondentsinSudanweremorelikelytoidentifyolderpeopleasfacingbarrierstoadaptation,duemainlytomobilitydifficulties,whilerespondentsinMaliweremorelikelyto35Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossidentifyyoungpeopleasfacingsuchbarriers,duetolimitedeconomicopportunitiesandresources.However,itisunclearwhytherewassuchdifference.InSudan,over80%ofrespondentsidentifiedolderpeopleasfacingsignificantbarrierstocopingandadaptation,whichwasreportedbyjustoveraquarterofthoseinMali.AsexplainedbyrespondentsinMali,thisisduetohealth–andmobility-relateddifficulties,anddifficultiesinadopting‘modern’agriculturalandlivelihoodtechniques.InMali,40%ofrespondentsidentifiedyoungpeopleasfacingsignificantbarrierstocopingandadaptation(comparedtojust2%inSudan).InMali,reasonsforthesebarriersechothoseidentifiedinSection5.3asunderpinningyoungpeoples’vulnerabilitytoenvironmentalchanges.Forexample,alackofemploymentandeconomicopportunitiesforyoungpeoplemeansthattheymaybelesslikelytohavesufficientfinancialresourcestosupportcopingandadaptationstrategies,andmayhavefeweropportunitiestocopeandadaptthroughchangestoworkorsubsistenceactivities.Peoplewithdisabilitiesalsofacebarrierstocopingandadaptation,duetophysicalmobilitydifficulties.One-fifthofsurveyrespondentsinMaliidentified‘other’groupsasfacingthegreatestbarrierstocopingandadaptation,andFGDrespondentshighlightedpeoplewithdisabilitiesasagroupfacingparticularbarriers.5.3AssistanceforcopingandadaptationInbothMaliandSudan,themostcommonlyreportedformsofassistancereceivedbypeoplefacingtheimpactsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalhazardsandchangesweretypesofshort-termhumanitariansupportforimmediateneedsthatdidnotdirectlyaddresskeychallengestocopingandadaptation(Figure5).Commonformsofassistancereceivedincludedfoodassistance(reportedby56%ofsurveyrespondentsinMaliand87%inSudan),cashandvoucherassistance(51%inMaliand61%inSudan),andnon-fooditemsforbasicneedssuchasshelterandsanitation(38%inMaliand46%inSudan).Theseformsofassistanceenablehouseholdstocopeby‘replacing’food,non-fooditems,andresourceslostthrougheventssuchasfloods,orbymitigatingthelossofharvestsandagricultural(andother)incomeduetoenvironmentalchanges(asdescribedinSection4.2).Whilethesetypesofsupportaddressurgentimmediateandshort-termneeds,andmaypotentiallyfreeupsomeresourcesforinvestmentsinlonger-termadaptativestrategies,theydonotdirectlyorsufficientlyaddressthekeychallengestocopingandadaptationstrategiesdescribedinSection5.2.Inparticular,theydonotmitigatethelackoffinancialresourcestosupportadaptiveinnovations(asopposedtosimplymeetingbasicneedsviacashassistance),ormeettheneedfortrainingandinformationonadaptationstrategiesandclimate-relatedhazards.InMali,thissupportwasprovidedbygovernmentandbyNGOs,whileinSudan,mostifnotallassistancecomesfromnationalandinternationalNGOs.InMali,forexample,FGDrespondentsdescribedtheprovisionofassistanceintheformofgrainstorageanddistributionbybothgovernmentandNGOs.InSudan,respondentsinDabatBosinandElganaareportedreceivingnosupportfromthenationalgovernmentorfromlocalauthorities–althoughthisrepresentstheexperiencesofstudyrespondentsandisnotnecessarilyreflectiveofoverall36Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrosspatternsofsupportprovision.RespondentsinIDPcampsinElfaomentionedthestate-levelgovernment’scoordinationofNGOsprovidingpost-disastersupport.Governmentresponsestodisasters,includingenvironment-relateddisplacement,arediscussedindetailinSection7.Whilepeoplecanseekoutothersourcesofsupporttolonger-termadaptation,thiscanentailrisks.Forexample,inMali,somerespondentsnotedthatitwaspossibletoobtaincreditfrombanks–butthispresentstheriskofcontributingtoindebtednessandfurthervulnerability.Thewidedifferencesinaccesstoshort-termgovernmentandNGOassistanceacrossresearchlocationsmayresultfromgeographicdifferencesintheimpactsofclimate-relatedandenvironmentalhazards,aswellastheunevenallocationofassistanceacrosslocationswithincountries.InMali,morerespondentsinKayesreportedreceivingfoodassistance,whileotherformsofassistance(e.g.financialassistance,non-fooditems)weremorefrequentlyidentifiedbyrespondentsinBamako.InSudan,foodassistancewasreportedbyallornearlyallsurveyrespondentsinDabatBosinandElfaoand65%ofthoseinElganaa;non-fooditemswerereportedbyallrespondentsinElfaobutnoneinDabatBosin;andfinancialassistancewasreportedby80to100%ofrespondentsinDabatBosinandElfaobutunder10%inElganaa.ThismayreflectthetypesofhumanitarianassistanceprovidedbydifferentnationalandinternationalNGOsacrossdifferentdisplacementsitesandcamps.Accesstoshort-termsupport(e.g.foodassistance,financialassistance,non-fooditems)wasreportedbyahigherproportionofrespondentsinSudan,whileaccesstolonger-termsupport(e.g.skillsandlivelihoodtraining,agriculturalinputs),thoughstillrelativelyuncommon,wasreportedbyaslightlyhigherproportionofrespondentsinMali.Thislikelyreflectsthetypesofenvironmentalchangesexperiencedbyrespondentsinthetwocountries:acutehazardssuchasfloodinginSudan,wherehumanitarianaidismorelikelytobeprovided,andslower-onsetenvironmentalchangesinMali,wherethereisgreaterscopeforfocusingonlonger-termadaptation.Trainingsupportandagriculturalinputswereidentifiedasimportantforadaptationtoenvironmentalchangesandchallenges,butfewrespondentsreportedbenefitingfromtheseformsofassistance.FGDrespondentsandintervieweesinMaliemphasisedtheimportanceofsupportsuchastrainingonagriculturalandherdingstrategies,subsidiesofagriculturalinputs,andmaterialsupportfortreeplantinginitiativesandtheconstructionoffirebreakstoprotectagainstbrushfires.However,onlyaquarterofsurveyrespondentsinMaliandunderone-fifthinSudanreportedreceivingtraining,whileonlyone-fifthofrespondentsinMaliandjustover10%inSudanreportedbenefitingfromagriculturalandfarminginputs,suggestingthatthesearenotwidelyavailable.AmongtheresearchsitesinSudan,peopleinElganaareceivedashorttrainingcourseonincomegenerationactivities,buttheothertwocommunitieshadnotreceivedsimilartraining.Respondentshighlightedtheneedtoincreasematerialsupportforlonger-termadaptationefforts.AccordingtoanintervieweeinKayes,‘AlltheStatedoesissensitisation[againstmigration],whichisnotlistenedtobytheseyoungpeople,’suggestingthateffortstosupportcopingandadaptationoughttoinvolvemoreconcretematerialsupportandassistance(e.g.fundsandequipmenttosupportlivelihooddiversification,agricultural37Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossinnovations,etc.).Similarly,asanotherintervieweeinKayesexplained,“Thegovernmentsensitisesthepopulation,especiallyyoungpeople,againstmigration,butthelackoffinancialresourcestotakecareoftheneedsoffamilies…pushesthemtowardsmigration.”Furthermore,respondentshighlightedaneedtoexpandsupportforcopingandadaptationinitiativesbeyondtheagriculturalsector,torespondtothevariedaspirationsofyoungpeople.InMali,FGDparticipantsandgovernmentandNGOrepresentativesemphasisedtheneedforstrategiesfocusingonyouth,includingprofessionaltrainingandemploymentcreationandsupport,financialsupporttoyouth-ledprojects,integrationsupportforyoungmigrants,andmonitoringofoutcomesandfollow-upsupport.PreviousresearchonmigrationinresponsetoenvironmentalchangesinMaliandNigernotesthatyoungpeople,especiallythosewithhigherlevelsofformaleducation,maynotfindfarmingattractiveandinsteadaspiretooccupationsoutsidetheagriculturesector(Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016)thatprovidehigherearningsandenableyoungpeopletomeetlifegoals(McCulloughetal.,2019).Finally,responsesinbothcountriesindicatedaneedtoexpandknowledgeofandaccesstoearlywarningsystemstosupportpreparednessforclimate-relatedhazards.RepresentativesoftheMaliRedCrossandIOMhighlightedtheimportanceofearlywarningsystemsandmeteorologicalinformationtoinformpreparednessanddecision-makinginresponsetoclimate-relatedrisks–toenablecommunitiestoputinplacemeasurestocopewithenvironmentalandclimate-relatedhazardsandchanges,andtomitigateassociatedrisks.However,only6%ofsurveyrespondentsinMalireportedbenefitingfromearlywarningmechanisms,suggestingthatthisisnotnecessarilyawidelyavailableorwidelyknownservice.AlackoftimelyweatherinformationwasalsoidentifiedasabarriertocopingandadaptationinSudan,likelyreflectingexperiencesofflood-relateddisplacement.AllcommunitiesinSudanreportedthattheyhadonlyheardaboutimpendingfloodsfromneighbouringcommunities,andnosurveyrespondentsreportedbenefitingfromearlywarningmechanisms.Forexample,inElganaa,thecommunityonlyheardaboutfloodrisktwodaysbeforeimpact–toolatetoadoptriskmanagementandcopingmeasures.Thesefindingsindicatetheneedformoresystematiceffortstoensureaccesstothesesystemsatthecommunitylevel,potentiallybuildingonexistingvolunteernetworkstosharealertsandcarryoutinitialassessmentsafterenvironmentalevents.38Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossFigure5.FormsofassistancefromgovernmentandNGOsreportedbysurveyrespondentsin█Maliand█Sudan39Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossFormsofassistanceMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Foodassistance56%50%62%87%100%65%98%Financialassistance(e.g.cashandvouchers,credit)51%68%34%61%100%8%80%Non-fooditemsforbasicneeds(e.g.shelter,sanitation)38%46%30%46%043%100%Medicalorhealthservices24%28%20%58%22%62%92%Skillsandlivelihoodstraining24%42%6%18%050%0Agriculturalinputs(e.g.seeds,tools)22%32%12%12%032%2%Psychosocialservices9%018%4%0014%Earlywarningmechanisms6%8%4%0000Supportforre-localisation5%6%4%1%004%Referraltootheragenciesorservices1%02%1%002%Noassistance19%14%24%————40Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossInMali,communitysupportinitiativesplayimportantrolesinfacilitatingcopingandadaptationefforts,alongsideorintheabsenceofsufficientgovernmentandNGOassistance.ThisechoespreviousstudiesinMalithatdescribetheimportanceofcommunity-basedcopingandadaptationstrategiesthroughmutualsupportandassistance(Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016).Roughlyone-fifthofsurveyrespondentsinMali(androughlyaquarterofthoseinKayes)reportedreceivingnoassistancefromgovernmentorNGOs,echoingfindingsfrompreviousresearchonmigrationinresponsetoenvironmentalchangesinMali(Hummel,2016).Similarly,someFGDrespondentsandintervieweesreportedthesupportprovidedbygovernmentauthoritieswasminimalatbestandthatmostsupportcamefromwithincommunities.Accordingtoafocusgrouprespondent,“Thestatedoesnotprotectmigrants.Itdoesnotsupportmigrants.Thestatedoesnotimprovepeople’slivingconditionstopreventthemfromleaving.”AsanationalNGOrepresentativestated,“Thegovernmenthasdonenothingaboutclimatechangeandhumanmobility[inourcommunity].Onlyneighbourshavecontributedtosupplyingthevillagewithdrinkingwaterbyinstallingawatertower,developingagardenarea…buildingthreeclassrooms…andthreelatrines.”Community-basedinitiativesdescribedbyFGDrespondentsandintervieweesincludelendingmoneythatwouldbereimbursedafterharvest,theestablishmentofcerealbanks,andincome-generatingactivitiesinvolvingthedevelopmentofsmallirrigatedareasinvillages,enablingpeopletomeettheirbasicneeds.RespondentsinSudandidnotspecificallydiscusscommunitysupportinitiatives,potentiallyreflectingtheirprecariousconditionsandlimitedresourcesresultingfromdisplacement.41Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCross6.Keyfindings:migrationtrendsanddecisionsinMaliandSudanRespondentsinMaliandSudanwereaskedtodescribetheoveralltrendsandnotablechangestheyhavenoticedinmigrationintoandoutoftheircommunities,includingtrendsandchangesintheregionsoforiginanddestinationofmigrants;thedurationofmigration;anddriversofandbarrierstomigration.20Theywerealsoaskedabouttherelationshipsbetweenenvironmentalfactorsandmigration,andhowmigrationcomparestoothercopingstrategiesinresponsetoenvironmentalchangesandchallenges.Respondentswereaskedtoreflectongeneralpatternsofmigration,aswellastheirownexperiencesofmigrationandtheexperiencesoffamilymembers.Thesechangingpatternsofmigrationtookplacenotonlyincontextsofenvironmentalchangebutalsoincontextsofwidereconomic,political,andsocialchange.6.1OveralltrendsinmigrationpatternsMostrespondentsinMaliandSudanobservedthatmostin-migration(i.e.migrationintorespondents’localities,fromelsewhereinthecountryorfromothercountries)involvespeoplefromneighbouringcountriesorfromwithinthesamecountry(Table3).MostsurveyrespondentsinMali(83%,including92%inKayes)observedthatin-migrantsarrivedfromotherlocalitiesinthecountry,whilenearlyhalf(andoverthree-quartersofthosefromKayes)reportedin-migrationfromthesamepartofthecountry.Significantnumbersofrespondents20Thissectionexaminesrespondents’perceptionsofmigrationpatterns,trends,andchanges,anddoesnotentailananalysisofspecificmigrationfigureswithintheresearchlocations.(44%)alsoreportedin-migrationfromneighbouringcountries(suchasSenegal,BurkinaFaso,Guinea,Côted’Ivoire,Algeria,accordingtointerviewees).InSudan,almostallrespondents(97%)inElganaapointedtoin-migrationfromaneighbouringcountry,reflectingpatternsofin-migrationfromSouthSudan.NearlyhalfoverallinSudanreportedin-migrationfromanotherlocalityinthesameregion.InDabatBosin,beforethemajorfloodin2021,youngSouthSudanesemenusedtomovetoSudantoworkasagriculturalseasonallabourersorinconstructionwork,whereassomeyoungwomenusedtoworkinbordermarketsasteamakers.InSudan,mostout-migration(i.e.migrationoutofrespondents’localities,towardotherpartsofthecountryortoothercountries)isalsoperceivedasbeingtowardsanotherlocationwithinthecountryortoaneighbouringcountry,buildingonlonghistoriesofmobilitybetweenSudanandSouthSudan.InElganaa,out-migrationtoadifferentlocalityorregionwithinthesamecountryortoaneighbouringcountrywasdescribedbyhalfofsurveyrespondentsormore,whileinElfaoallrespondentsobservedthatout-migrationismainlytowardadifferentregioninthesamecountry.AllrespondentsinDabatBosinreportedthatout-migrationismainlytowardaneighbouringcountry(i.e.betweenSudanandSouthSudan).TheyexplainedthatpeoplefromDabatBosinhavebeenmovingforalongtimebetweenSudanandSouthSudan,includingafterSouthSudan’sindependencefromSudanin2011,42Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossduetoinsecurity,transhumancelivelihoods,andcross-bordertrade.Patternsofout-migrationappearmorevariedinMali,withcross-bordermigrationtowardneighbouringcountriesandotherworldregionsdescribedmorefrequently.WhilemostsurveyrespondentsinMali(71%)observedthatmostout-migrantsheadtootherregionsofthecountry,largenumbersofrespondents(between55and66%)pointedtomigrationdestinationsfurtherafield,includingneighbouringcountries,otherAfricancountries,orcountriesoutsideAfrica.SurveyrespondentsinBamakoweremorelikelythanthoseinKayestohighlightout-migrationtoaneighbouringcountry,whilethoseinKayesweremorelikelytoidentifyanotherAfricancountryoracountryoutsideAfrica(e.g.inEuropeorGulfstates)asthemainout-migrationdestination,reflectingitspositionasahuboflonger-distanceinternationalmigration.Table3.TrendsinmigrantsourcesanddestinationsreportedbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanSourceordestinationregionMaliSudanTotalBamako(N=50)Kayes(N=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Originsofin-migrantsDifferentlocalityinthesameregionofthecountry48%20%76%n/an/a48%n/aDifferentregioninthesamecountry83%74%92%n/an/a3%n/aNeighbouringcountry44%40%48%n/an/a97%n/aAnotherAfricancountry9%8%10%n/an/a0n/aCountryoutsideAfrica5%4%6%n/an/a0n/aDestinationsofout-migrantsDifferentlocalityinthesameregionofthecountry18%22%14%29%078%2%Differentregioninthesamecountry71%94%48%52%060%100%Neighbouringcountry66%92%60%52%100%50%0%AnotherAfricancountry61%48%74%0000CountryoutsideAfrica55%22%88%1%002%43Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossMigrationfromruraltourbanareasisseenasakeytrendininternalmobilityinMaliandSudan,likelyduetoanticipatedeconomicopportunities–althoughrespondentsinSudanalsohighlightedtrendsinrural-to-ruralmigration(linkedtominingandagriculturalopportunities).21Rural-to-urbanmigration(especiallytowardnationalcapitals)wasreportedbyroughly40%ofsurveyrespondentsinbothMaliandSudan–potentiallydrivenbyasearchforeconomicopportunities(asdiscussedinSection6.2).However,responsesvariedwidelyacrossresearchsites.InMali,nearly90%ofrespondentsinBamakoidentifiedrural-to-urbanmigrationasthemostcommon(likelydrawingupontheirownmigrationtrajectories),butnorespondentsinKayesreportedthesame(focusinginsteadoncross-bordermigration).InSudan,nearly90%ofsurveyrespondentsinElfaofocusedonrural-to-urbanmigration,comparedtoroughlytwo-thirdsinElganaaandjust2%inDabatBosin.Conversely,overhalfofrespondentsinElganaaidentifiedrural-to-ruralmigrationasthemostcommontypeofinternalmobility.ThesetrendsmayreflectthedifferenttypesofeconomicopportunitiesavailabletomigrantsindifferentpartsofSudan:workopportunitiesinurbancentres,aswellasartisanalgoldminingareasandlarge-scalemechanisedfarmingschemesinruralareas.RespondentsinbothMaliandSudanobservedthatmigrationismainlytemporaryorseasonal,ratherthanpermanent–althoughthisvariedacrosslocationswithincountries,reflectingmorelocalisedpatterns21IthasbeenobservedthatthisalsooccursinMali,inthedryseasonandonalesserscale.ofmobility.AtleasthalfofsurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanreportedthatmigrationismainlytemporary,whileoveraquarterofthoseinMaliandone-fifthinSudanobservedthatmigrationismainlyseasonal.However,cleardifferencesemergedwithinbothcountries.InMali,respondentsinBamako(62%)weremorelikelythanthoseinKayes(38%)toidentifymigrationastemporary,whilethoseinKayesweremorelikelytoreportpermanentmigration(30%,comparedtojust6%inBamako),potentiallyreflectingtheprominenceofinternationalmigrationthere.InSudan,respondentsinElganaaandElfaodescribedmigrationmainlyastemporary(82%inElganaa,48%inElfao)orseasonal(50%inElfao).InElfao,forexample,respondentsexplainedthatmostinternalmigrationoccursonaseasonalbasistowardagriculturalschemestoworkinlabour.InDabatBosin,migrationwasdescribedastemporaryorofunknownduration(likelyduetotheuncertaintycharacterisingflood-relateddisplacement).InMali,alargeproportionofsurveyrespondentsreportedthatreturnmigrationisincreasing,duetoeconomic,political,andsanitary/healthcrises(notablytheCOVID-19pandemic)andmorerestrictiveresidenceandmigrationpolicies.FGDrespondentsandintervieweesidentifiedthereturn(oftenforced)ofmigrantsfromcountriessuchasLibyaorFranceasanimportantmigrationtrendinMali.ThisisreflectiveofMalihavingbecomeareceivingcountryfordeportedandreturnedAfricanmigrantsfromnorthern44Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossAfricancountries(e.g.Libya,Algeria)andEurope(TraunerandDeimel,2013).InMaliandSudan,adultmenwereidentifiedasthemostlikelytomigrate.Overall65%ofrespondentsinMaliand53%ofthoseinSudansharedthisperception,whileyoungermenspecificallywereidentifiedasmostlikelytomigrateby50%and64%,respectively,ofrespondentsinMaliandSudan.However,overhalfofrespondentsinBamakoidentifiedyoungwomenaslikelytomigrate,potentiallyreflectingagreaterpropensityamongyoungwomenformigrationtowardurbancentres.InSudan,allsurveyrespondentsinDabatBosinreportedthatbothmenandwomen(adultsandyoungpeople)arelikelytomigrate,likelyreflectingtheirexperiencesofflood-relateddisplacementofwholecommunities.6.2DriversofmigrationRespondentsinMaliandSudanwereaskedtoreflectondriversofmigrationintwoways,firstbyreflectingonthefactorsthattheyperceivedasunderpinninggeneralpatternsofmigration,andsecondbyreflectingontheirownmigrationdecisions(orthoseoftheirfamilymembers).Overall,reasonsformoving,orconsideringmoving,weremultipleandintersecting,encompassingpolitical,economic,social,andenvironmentalfactors.Inbothperceptionsofoveralltrendsandrespondents’ownmigrationexperiences,economicfactorswereidentifiedastheprimarymotivationformigrationinMaliandSudan(exceptamongthosedisplacedbysudden-onseteventssuchasfloods)(Table4).AsdiscussedinSection3.3,thisreflectsfindingsinthewiderliterature.InMali,economicmotivations(e.g.seekingbetterworkingandlivingconditions)wereidentifiedasunderpinninggeneralmigrationpatternsbynearlyallsurveyrespondents(98%),whileallrespondentsinBamakoandKayesreportedthateconomicfactorsdrovetheirownmigrationdecisions.FGDparticipants,especiallyyoungermen,sharedsimilarmotivations.InSudan,nearlyallsurveyrespondentsinElfao(94%)andElganaa(nearly80%)identifiedeconomicfactorsasthemainreasonfortheirownmigration(thoughinDabatBosin,allrespondentsidentifiedsudden-onsetenvironmentalhazardsasdrivingdisplacement).Environmentalfactors–especiallyrainfallchangesandlackofaccesstonaturalresources(andwiththeexceptionofsudden-onseteventssuchasfloods)–weretypicallyidentifiedassecondarytoeconomicfactors,althoughthereissignificantoverlapwitheconomicmotivationsgiventheimpactsofenvironmentalchangeonlivelihoodsandfoodinsecurity.InMali,precipitationchangesaffectinglivelihoodactivities,lackofaccesstonaturalresources,andfoodinsecuritywereeachidentifiedasprimarydriversofgeneralmigrationpatterns,andasdriversofrespondents’ownmigrationdecisions,byaboutathirdofsurveyrespondents.Asnotedabove,environmentalchangesandchallengesmaybelinkedtoeconomicfactorsthroughtheirimpactsonindividualandhouseholdsocioeconomicstatusandinturnincreasedpressuresformigration.Inrelationtobothgeneralmigrationpatternsandrespondents’ownmigrationdecisions,precipitationchanges,resourceaccess,andfoodinsecuritywereallidentifiedbymorerespondentsinBamakothaninKayes.ThismayreflectchallengesfacedpreviouslybyrespondentsinBamako,i.e.priortotheirownmigration.InSudan,allrespondentsinDabatBosinidentifiedsudden-onsetenvironmentalhazards(floods)asthereasonsfortheir45Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossdisplacement,asdid90%ofthoseinElfaoandnearly70%ofthoseinElganaa.However,respondentsinElganaaandElfaoalsoidentifiedotherenvironmentalfactorsasreasonsfortheirownmigration,thoughinbothcasestheseweresecondarytoeconomicmotivations.RainfallchangesaffectinglivelihoodswerereportedbyathirdofrespondentsinElganaaandoverhalfofthoseinElfao,andfoodinsecuritywasidentifiedbynearlytwo-thirdsofrespondentsinbothsites.Thissuggeststhatevenbeforethefloods,slower-onsetenvironmentalchangeswerecontributingtomigrationpressures.Table4.Primaryreasonsforsurveyrespondents’ownmigrationdecisionsinMaliandSudanMainreasonsformigrationMaliSudanTotal(N=72)Bamako(n=34)Kayes(n=38)Total(N=165)DabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Economic(searchforbetterworkingandlivingconditions)100%100%100%57%0%78%94%Rainfallchangesaffectlivelihoodactivities36%65%11%28%0%33%54%Lackofaccesstonaturalresources32%62%5%16%0%10%42%Foodinsecurity31%41%21%42%0%62%66%Security(e.g.conflict)18%21%16%2%0%0%6%Environmentalshocks(e.g.flooding)13%18%8%85%100%67%90%Temperaturechangesaffectingsubsistenceactivities6%9%3%5%0%0%18%46Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCross6.3PerceivedchangestomigrationpatternsMostrespondentsinMaliandSudanreportthatmigrationpatternsarechangingintheirlocalities,inparticularreportingincreasesinbothin–andout–migration.Increasesinin-migrationandout-migrationwerefrequentlyreportedinMali,eachidentifiedbynearlythree-quartersofsurveyrespondents.However,respondentsinBamakoweremorelikelythanthoseinKayestoreportsuchincreases.Nearly90%ofrespondentsinBamakoreportedanincreaseinout-migration,comparedtojustover50%inKayes.ThismayreflecttheBamakorespondents’ownexperiencesofmobility,aswellaschangesinmobilitypatternswithinandthroughBamako,asbothadestinationandincreasingtransitpoint.Forexample,researchonyouthmigrationinMalireportsthatmigrantsfromotherpartsofthecountrypassthroughBamakoontheirwaytoEuropeorwhenreturningfromEuropetotheirhomecommunities(Daum,2014).InSudan,anincreaseinout-migrationwasreportedbymostsurveyrespondents(90%,rangingfrom75%inElganaato100%inDabatBosin),whileanincreaseinin-migrationwasreportedonlybyrespondentsinElganaa(althoughallrespondentstherenotedsuchanincrease).InElganaa,patternsofincreasingin–andout-migrationexistsimultaneously,asrespondentsdescribedout-migrationtourbancentresandseasonallytoagriculturalfarms,alongsidein-migrationfromSouthSudaneserefugeesthatrecentlycrossedtheborderintoSudan.InMali,respondentsinKayesweremorelikelythanthoseinBamakotoreportdeclinesinbothin–andout-migration,potentiallyduetochangesinpatternsofcross-bordermobility.Declinesinin-andout-migrationwereobservedby25%and41%,respectively,ofsurveyrespondentsinKayescomparedtojust2%ofthoseinBamako.GivenKayes’positionasahubofcross-bordermobility,thismayreflecttheimpactsofmigrationrestrictions(spanningbothmorerestrictivemigrationpoliciesandCOVID-relatedrestrictions)andotherfactorsonpatternsofcross-bordermovement.InSudan,respondentsdescribedchangesingenderedpatternsofmigration,withyoungmarriedandunmarriedwomenmovingfurtherawayformonthsatatimetoworkintheagriculturalsector.Thischange,describedbyclosetohalfofrespondents,standsincontrastto‘traditional’normsandcustoms,andwasdescribedasresultingfromrecentenvironmentalchanges.However,thesefindingsarebasedonlyonrespondents’perceptionsofmigrationpatterns;itisunclearwhethertheyarereflectedinexistingmigrationdata.Normally,active-agewomenworkascasualwagelabourersinfarmingactivities,suchashandweedingandharvestinginnearbyfields.Now,respondentsrelayedthatwomenarealmostequallyaslikelyasmentomovefordistantagriculturalopportunities.Womenwhomovetaketheirbabiesandmustmanagethedualburdenofagriculturallabourandchildcare,incontextsofharshagriculturallabourconditionsnotsuitableforchildren.Thelong-termimplicationsofthisvaryandincludechildmalnutritionandtheweakenedhealthofmothers.InMali,changesinmigrationpatternswereobservedtohaveoccurredmainlyoverthepastfourto10years,reflectingmoregradualchangesinmigrationtrends(aswellasslower-onsetenvironmentalchanges).Mostsurveyrespondents(62%)reportedthatthesechangeshaveoccurredoverthepastfourto10years–althoughrespondentsin47Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossBamakoweremorelikelythanthoseinKayestoreportthatchangeshaveoccurredinthepastfourto10yearswhilerespondentsinKayesweremorelikelytoreportthatchangeshaveoccurredoveraperiodofmorethan10years.ThismayreflectKayes’longhistoryasamigrationtransithub,whereearlyindicatorsofchangingmigrationpatternsmaybemoreobservablegiventhescaleofmigrationflows.InSudan,changesinmigrationpatternswereobservedtohaveoccurredmainlyinthepastonetothreeyears,reflectingtheimpactsofmorerecentpatternsofsudden-onsetenvironmentalhazards(i.e.flooding).Mostsurveyrespondents(nearly70%)reportedthatthesechangeshaveoccurredinthepastonetothreeyears.Thiswasreportedbynearlyall(95%)ofrespondentsinDabatBosin,likelyduetoexperiencesoffloodingandassociateddisplacement.ThisechoespreviousreportsthatfloodsinSouthSudanandSudanhavebeenincreasinglysevereanddestructiveinthepastthreeyears(Tiitmamer,2020;Elagibetal.,2021).RespondentsinElganaaandElfaoweremorelikelythanthoseinDabatBosintoreportthatthesechangeshavebeenhappeningforlonger(20%ofrespondentsinElganaaandnearly40%ofthoseinElfaoobservedchangesoverthepastfourto10years).6.4MobilityandadaptationMorerespondentsinSudanthaninMaliobservedthatenvironmentalchangesarecontributingtoageneralincreaseinmobility,likelyreflectingdifferencesinthetypeofenvironmentalchangesandchallengesobservedbyrespondents.InSudan,nearlyallrespondentsoverall(93%),includingallrespondentsinElganaa,observedthatenvironmentalchangesarecontributingtoageneralincreaseinmobility–likelyreflectingtheimpactsofintensifiedfloodingondisplacementinrecentyears.InMali,justoveraquarterofsurveyrespondents(27%)reportedthatenvironmentalchangesarecontributingtoincreasedmobility.ThiswasobservedbymorerespondentsinBamako(45%)thaninKayes(9%),whichmayreflectrespondentdemographics,withagreaterproportionofthoseinBamakohavingmigrated.InMali,15%ofsurveyrespondents–andnearlyone-fifthofthoseinBamako–observedthatenvironmentalchangesarecontributingtoadecreaseinmobility.Whilelesscommonlyreportedthanincreasingmobility,thisisnonethelessimportant:itmayreflecthoweconomicimpactsofenvironmentalchangecanreducehouseholdincomeandinturnreduceoptionsformobility,echoingpreviousresearchdescribedinSection3.3.AsoutlinedinSection5.1,migrationisconsideredacommonadaptationstrategyinbothMaliandSudan(seeFigure4,inSection5.1).OverhalfofsurveyrespondentsinMaliidentifiedmigrationasacommonadaptationstrategyinthefaceofenvironmentalorclimate-relatedchanges–rangingfrom70%inBamakotojustathirdinKayes.Thislikelyreflectsrespondentdemographics,withagreaterproportionofthoseinBamakohavingthemselvesmigrated(seeSection2.4).InSudan,nearlyallsurveyrespondents(98%)identifiedmigrationasanadaptationstrategy.ThislargemajorityincludedallrespondentsinDabatBosinandElganaa–reflectingtheirownexperiencesofdisplacementduetoflooding.Forrespondentsidentifyingmigrationasanadaptationstrategyinresponsetoenvironmentalchangesandchallenges,48Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossthedestinationsanddurationofmigrationmayvarywidely,reflectingfindingsdiscussedinSection6.1.However,theimpactsofenvironmentalchangesonlivelihoodsandincome(asdiscussedinSection4.2)maylimitpossibilitiesformoreexpensivelong-distanceandinternationalmigration.InMali,migrationwasdescribedasa‘lastresort’inresponsetoenvironmentalchanges,onlyoccurringwhennootheralternativesexistbecausepeopleprefertostayintheirowncommunities–andyoungpeopleoftenshouldertheburdenofhavingtomigrate.ThiswasfrequentlyhighlightedbyFGDparticipantsandinterviewees,whileadesiretostayinplacewasidentifiedasakeybarriertomigrationbysurveyrespondents,asdiscussedinSection6.5.AsoneFGDrespondentexplained,“Ifwemanagetohaveastrategythatcanhelpusstay,somuchthebetter.Ifnecessary,ifwehavethepossibilitythroughmigrationtomanageandsend[money]toourparents,we’lldothat.Wehavenootherstrategybutmigration.”Youngpeopleoftenshouldertheburdenof‘lastresort’migrationinordertosupporttheirparentsandfamilies.AsaFGDparticipantinKayes(Mali)explained,discussinghisownexperience,“Giventhepovertyweweregoingthrough,myageandtheenergyIhadallowedmetodocertainthings.[Wehad]nosourceofincomeexceptland,butthishardlyproducedanything…Thedecisionismadetoleaveevenifthere’stheriskofdeath.”Similarly,accordingtoanintervieweeinKayes,“Youngpeoplewithno[opportunities]prefertomigrateeveniftheyhavetodieatsea.Thereisnoalternativesolutiontotheirproblemsaslongastheproblemofmoneyisnotaddressed.Europeansshouldunderstandthatnoonewantstoleavetheirlocalityforsomewhereelseinordertodieinthewater.Youngpeopleprefertostaybuttheydon’thaveasolution.”‘Tippingpoints’,wherecopinginplacewasnolongerpossible,weremainlyassociatedwithacuteenvironmentalhazards,suchasfloodingorcropfailure.InMali,FGDparticipantsdescribedcontinuedshockssuchasflooding,acutelackoffood,andpoorcropproduction(orfailedcrops)afterharvestasunderpinningmigrationdecisions.InSudan,almostallsurveyrespondents(98%)reportedthatmigrationbecamethemaincopingoptionasaresultoflarge-scalesuddenfloodingevents,whichrenderedtheirareasuninhabitable.Forexample,inElganaa,whenfarmsweretotallysubmergedbyfloods,localcommunitieschangedtheirworkandlivelihoodactivitiesfromfarmingandherdingtowagelabouring,oradaptedbymovingawayfromthearea.Whilesuch‘external’tippingpointswerediscussedmostfrequently,somerespondentsdescribedmoregradualdecisionsaboutmigration.Insuchcases,thedecisiontomovewasmadeearlier,andmigrationoccurredoncethenecessaryresourcesbecameavailable–once(foryoungerpeople)parentswerepersuadedtoallowmigrationtotakeplace,lodgingwasarranged,andmoneyforthecostsoftravelsecured.49Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossAswellasbeinganadaptationitself,migrationcanalsoprovidethemeanstosupportotherin-placeadaptationinitiativesthroughremittances–butthisconnectionrisksbeingoverstated,andnotallmigrantsareabletosupportsuchinitiatives.Echoingfindingsfrompreviousresearch(discussedinSection3.2),intervieweesinMalidescribedhowmigrationandwideradaptationareinterconnected,asremittancessentbymigrantscansupportadaptation-focuseddevelopmentsintheirhomecommunities,suchashydro-agriculturalinfrastructure,irrigationsystems,smalldams,orfishfarminginitiatives.AMaliRedCrossrepresentativedescribedinitiativesinKayesthataresupportedbymigrantsanddiasporamembers:“Thecontributionthat[migrants]bringtothecommunityintermsofinvestments…thehealthcentre,waterpointsorreforestation,supportforagricultureandmarketgardening…Thecommunitieswhoarethere,theyseemigrationasreallyapositive…Thereareprojectswhereweshouldsupportthecommunityonthebasisofanexpressionofneeds–createanareawithplantationsformarketgardeningandothers–butthemeansfortheprojectwerelimited…ItwasthediasporafromthisvillagewhowasinFrancewhosetupaboreholetoallowthe[garden]tobewatered.”However,thesemigration-adaptationconnectionsarenotguaranteed,andriskbeingoverstated.Forexample,alocalofficialinKayesexplainedthatwhilemigrantscontributeconsiderablytothedevelopmentoftheirhomecommunities,resourcesprovidedbymigrantsareofteninvestedininfrastructurethatdoesn’tdirectlyaddressenvironmentalrisksandvulnerabilities.Additionally,asdiscussedinSection6.7,notallmigrantsareabletosupportsuchprojectsgiventhatmanymigrantsareunabletoregularlysendmoneytotheirfamilies–withjust3%ofsurveyrespondentsinbothMaliandSudaninreportingcontributionstodevelopmentprojectsincommunitiesoforigin.Inmanycases,remittancesareonlysufficienttomeetfamilies’basicneeds,andarenotabletocontributetolargeradaptationefforts.6.5BarrierstomigrationOlderpeoplewereidentifiedasthegroupleastlikelytomigrate,andwomenandpeoplewithdisabilitieswerealsodescribedasfacingbarrierstomigration–highlightingtheintersectingandcompoundingeffectsofvulnerabilitiestotheimpactsofenvironmentalchange,generalbarrierstocopingandadaption,andspecificbarrierstomobilityalonglinesofgender,age,and(dis)ability(asdiscussedinSection4.2andSection5.2,respectively).OlderpeoplewereidentifiedastheleastlikelytomigratebythemajorityofsurveyrespondentsinMali(76%)andSudan(96%),duetophysicalmobilitychallengesanddifficultiesfindingemployment.Similarchallengesfacepeoplewithdisabilities.InMali,nearlythree-quartersofrespondentsreportedthatwomenareleastlikelytomigrate,duetomarriageandfamilyrestrictions.InSudan,despitechangestogenderedmigrationpatternsdescribedinSection6.3,socialrestrictionsonwomenwerestillconsideredabarriertomobility.Familyreasonsandadesiretostayinplacewerethemostfrequentlyidentified50Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossbarrierstomigrationreportedinMaliandwerealsoreportedinSudan,reflectingstrongattachmentstocommunityaswellaspotentiallossesassociatedwithmigration(Table5).InMalifamilyreasonswereidentifiedasakeybarriertomigrationbyover90%ofsurveyrespondentsandnearly60%ofthoseinSudan(androughly70to80%ofthoseinElganaaandElfao).AlthoughFGDrespondentsinMalidescribedfamilypressuresinrelationtoyoungpeopleshoulderingtheburdenformigration(asdiscussedinSection6.4),thesesurveyresponsessuggestthattheimpactsoffamilyrelationsonmobilityacrosstheSahelaremorecomplex.Whilesomemigrantsmayexperiencepressuresfromfamilymemberstomove,othersmaybepreventedfrommovingduetofamilialrestrictions(especiallyforwomen),responsibilityforsupportingfamilymembersthroughin-placeworkorcarelabour,lackoffinancialsupportfromfamilymembersformigration,oradesiretoremainwithfamily.ThisechoespreviousresearchinMali,whichdescribestheimportanceoffamilytiesandresponsibilitiesandattachmenttoplaceasreasonsfornon-migration(Sauvain-Dugerdil,2013;KirwinandAnderson,2018).OverhalfofsurveyrespondentsinMali(53%)identifiedadesiretostayinplaceasthemainbarriertomobility.Thishighlightstheimportancenotonlyoffamilybutofpeople’sattachmenttotheirlocality(basedonelementsofpersonal,communal,cultural,spiritual,andhistoricalsignificance).AdesiretostayinplacewasreportedbyunderafifthofthoseinSudan,potentiallyreflectingtheimpactsofincreasinglysevereflooding.InSudan,financialbarrierswereidentifiedasthemainbarriertomigration,butwerereportedlessfrequentlyinMali.NearlyallrespondentsinSudan(83%),especiallyinDabatBosin,describedalackoffinancialresourcesasabarriertomigration.Thismaybelinkedtorespondents’ownfinancialstatusintheaftermathofflood-relateddisplacementandcurrentconditionsinIDPorrefugeecamps.InMali,justathirdofsurveyrespondentsdescribedfinancialbarrierstomigration,althoughthesewereidentifiedbymorerespondentsinKayesthaninBamako(potentiallyduetotheprofilesofrespondents,withmostrespondentsinBamakohavingalreadymigrated).FGDrespondentsinbothBamakoandKayesdescribedfinanciallimitationsasakeybarrier,thoughitisunclearwhytherewassuchdifferencecomparedtosurveyrespondents.InMali,respondentsalsohighlightedlogisticalbarrierstointernationalmigration,specificallydocumentationrequirements(e.g.residencepermits)fordestinationcountriesandmorerestrictivemigrationpolicies.Thiswasidentifiedbysomeasanimportantchangelimitingpossibilitiesformobility,asoneFGDparticipantinKayesexplained:“Before,travelingtoFrancewaseasy.Thingshavenowchanged.Before,itwasenoughtohavethepassport…Now,havingapassportandtransportationarenotenoughtoreachFrance.”51Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCross6.6MigrationoutcomesInMali,mostrespondentsfelttheirsocialandeconomicconditionshadimprovedaftermigration,duetonewemploymentorbusinessopportunities,anabilitytomeettheirbasicneeds,andtheabilitytosendfundstosupporttheirparentsandfamiliesintheirhomecommunities.However,theyalsodescribedmigrationasbeingassociatedwithnumeroussocialandeconomicchallenges.MorerespondentsinKayes(72%)thaninBamako(56%)reportedthattheirsocialandeconomicconditionshadimprovedaftermigration,whilethoseinBamako(20%)wereslightlymorelikelythanthoseinKayes(12%)toreportthattheirconditionshaddeclined,potentiallyreflectingchallengesassociatedwithmigrationtourbancentres.Reflectingpreviousliteratureonthechallengesfacedbymigrants(discussedinSection3.5),FGDrespondentsalsodescribeddifficultiesassociatedwithmigration,notablychallengesinfindingwork,housing,andfood;financialdifficulties;healthconcernsinurbansettings(includingillnessandaccidents,andlikelyalsobarrierstoaccessinghealthservices);andpressuresassociatedwithresponsibilityforsupportingfamiliesintheirhomecommunities.Involuntarydisplacementduetosudden-onsetenvironmentalhazardsandconflictisassociatedwithparticularchallenges,includinglossofsocialstatus,resources,andproperty.InSudan,forinstance,wheremostrespondentshadexperiencedforceddisplacementduetoflooding,anoverwhelmingmajorityofrespondents(88%)reportedthattheirsocio-economicconditionsdeclinedaftermigrating.Theyexplainedtheyarecurrentlylivingunderthechallengesofbeingrefugeesinaforeigncountry,aswellascopingwithwidespreadlossesdueflooding,includinglossoflife,assets,houses,livestock,andlivelihoodactivities,lackofaccesstoschooling,andseparationfromhouseholdmembersandfromhome.Table5.BarrierstomigrationidentifiedbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanMainbarriersMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Familyreasons91%90%92%59%33%68%78%Adesiretostayinplace53%62%44%16%16%20%10%Lackoffinancialresources33%18%48%83%93%70%88%Useofin-placecopingstrategies18%10%26%2%05%0Lackofinformation4%08%13%20%17%2%52Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossInMali,FGDrespondentswhohadbeendisplacedduetoconflictdescribedchallengesassociatedwiththeexperienceofdisplacementandthelossofresourcesneededtonavigatesocialandeconomicprocesses.Theseincludedthelossofidentificationdocuments,mobilephones,meansoftransportation(e.g.motorcycles),andproperty,makingitdifficulttosettleandadaptaftermoving.Similarchallengesmayalsoaffectpeopledisplacedbyrapid-onsetenvironmentaleventssuchasfloods.AsonemaninBamakoexplained,“Wedidnotsettlehereforpleasure.Thatweleaveourlocalityforanotherisadifficultyinitself.”6.7TiesbetweenmigrantsandtheirfamiliesandcommunitiesoforiginFamilyandcommunitymemberssometimesprovidematerial,logistical,andemotionalsupportbeforeandduringmigrationjourneys–butmanymigrantsdonotreceiveanymaterialsupport.Overone-fifthofsurveyrespondentsinMalireportedthatfamilyandcommunityprovideassistance,advice,orguidancetofacilitatemigration.FGDrespondentswhowerethemselvesmigrantsexplainedthatfamilyandpeernetworksprovidedthemwithfinancialsupport(e.g.fundsfortransport)orlogisticalsupportsuchashelpingtoobtainadministrativedocuments(e.g.identitycards).Justunderaquarterofallsurveyrespondents(notonlymigrants)inMaliregularlyreceivedfoodormaterialobjectsfromfamilyandcommunitymembers,androughlyone-fifthwereregularlysentmoney.InSudan,aboutone-thirdofsurveyrespondentsreportedregularlyreceivingmoneyfromfamilyorcommunitymembers–thoughthiswasreportedbyroughlyhalfofrespondentsinElganaaandElfaocomparedtojust5%inDabatBosin,likelyduetoexperiencesofforceddisplacementofentirehouseholdsandcommunities.InMali,overaquarterofsurveyrespondentsreportedreceivingnosupportfromfamilyandcommunitymembers.AsFGDrespondentsinMaliexplained,provisionoffinancialsupportisclearlynotpossibleforallfamilies(duetoeconomicconstraints).Furthermore,supportfromfamilyvariesaccordingtothenatureofdisplacementormigration.Forinstance,whenmovementoccursduetoinsecurityortorapid-onseteventssuchasfloods,familiesareoftenunabletoprovidefinancialsupport.Migrantsprovidesupporttotheirfamiliesandcommunitiesoforiginbyregularlysendingmoney,food,orothergoods,althoughthiswasreportedbymorerespondentsinMalithaninSudan,andforsomemigrantsaninabilitytoprovidesuchassistancemaybeasourceofshame.OverhalfofsurveyrespondentsinMali(54%)reportedthatmigrantsregularlysendmoneytofamilyandcommunitymembers,whileoverathird(37%)reportedthatmigrantsregularlysendfoodorothergoods(e.g.medication).FGDparticipantswhoweremigrantsdescribedthemaintenanceofclosetieswithfamilymembersandcommunitiesoforigins,mainlythroughsendingmoneyaswellasclothing,medication,andprovisions.Onegroupnotedthatremittancestofamiliesaccountedforbetween70and90%ofsomemigrants’income.InSudan,athirdofsurveyrespondents(and45to50%ofthoseinElganaaandElfao)reportedregularlysendingmoneytofamilyandcommunitymembers,although53Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossveryfew(4%)reportedsendingfoodorothergoods.AccordingtosomeFGDrespondents,forsomemigrantsaninabilitytoprovidesuchassistancemaybeasourceofshame.Referringtotheirownmigrantfamilymembers,theyexplainedthatwhentheyleft,theyintendedtosendmoneybacktotheirfamilies.However,notallofthemhavemanagedtodoso.Theymayfeelshamewhentheyareunabletomeettheseobligations.MostmigrantrespondentsinMaliandSudanreturntotheirlocalitiesoforiginonlyoccasionallyorrarely,andreturnmainlytovisitfamily.Occasionalorrarereturnvisitswerereportedbynearly90%ofsurveyrespondentsinMaliandnearly60%ofthoseinSudan.However,inSudan,veryfewrespondentsinDabatBosin(7%)reportedmakingreturnvisits,giventheimpactsoffloodingintheirlocalitiesoforigin.Themainreasongivenbyrespondentsforreturningistovisitfamily,reportedbyoverthree-quartersofsurveyrespondentsinMaliandbetweenabout60and70%ofrespondentsinSudan.AsFGDrespondentsinMaliexplained,someyoungerwomenandmenmayreturntotheirhomecommunitiestohelptheirparentswithagriculturalwork.Returnvisitsforspecial(e.g.religious)occasionsandprofessionalorbusinessactivitieswereeachreportedmorefrequentlybysurveyrespondentsinSudanthaninMali.MostmigrantrespondentsinMaliplantoreturntoliveintheirlocalityoforigin(i.e.long-termorpermanentreturn),whilemostmigrantrespondentsinSudaneitherwishtoreturnbutarenotabletodoso,orhavenoplanstoreturn,forfinancialandenvironmentalreasons.Overthree-quartersofsurveyrespondentsinMali(77%)reportedthattheyplantoreturntotheirlocalityoforigin,althoughthiswasreportedbymorerespondentsinKayes(86%)thaninBamako(68%)–potentiallybecauseoverhalfofrespondentsinBamakohadmigratedoversixyearsago(seeSection2.4)andweremorelikelytobesettledintheir‘new’location.Similarly,onlyrespondentsinBamako(20%)reportedthattheydonotplantoreturn.BetweenaquarterandathirdofsurveyrespondentsinSudanreportedbeingunabletoreturnorhavingnoplanstoreturn,althoughresponsesvariedacrossresearchsites.MostrespondentsinDabatBosin(76%)wantedtoreturnbutwereunableto–forfinancialreasonsandbecausetheareaisstillflooded–whereasthoseinElfao(80%)didnotintendtoreturnduetoincreasingfloodeventsintheirlocalityoforigin.54Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossPeople’smigrationoptionsandtrajectoriesinresponsetoenvironmentalandclimate-relatedchangesintheSahelareinfluencedbyintersectingnational,regional,andinternationalmigration,climateanddevelopmentpoliciesandlegalframeworks(seee.g.Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016).ThissectionexploreshowthegovernmentsinMaliandSudanarerespondingtoclimateandenvironment-linkedmigrationandsituatesthemwithinthewidercountryandregionalframeworksthatrelatetohumanmobilityintheregion.7.1RegionalandnationalresponsesMigrationpoliciesinSudanandMaliareinfluencedbywiderregionalmobilityframeworksintheSahel.Theregionalframeworksreviewedtendtogivelittleacknowledgementoforattentiontotherolethatmigrationmightplayaspartofcopingandadaptationstrategiesinresponsetoenvironmentalandclimatechange.22TheseincludetheAfricanUnionMigrationPolicyFramework,whichidentifiesclimatechangeasa‘majorpushfactor’underpinningmigrationandwhichaimstoaddressitsrootcausesto‘bettermanage’migrationanddisplacement(AU,2018a).TheAU’sProtocoltotheTreatyEstablishingtheAfricanEconomicCommunityRelatingtoFreeMovementofPersons,RightofResidenceandRightofEstablishmentsets22Seealsodisasterdisplacement.org/portfolio-item/implementing-the-commitments(Mokhnacheva,2022)outrightstomobility,butwithnospecificreferencetoenvironmentalorclimaticdriversofmigration(AU,2018b).IGAD’sRegionalMigrationPolicyFrameworksuggeststhat‘migration-environmentinterrelatedpoliciesareinevitable’forMemberstatesbutdoesnotpresentdetailedresponsesbeyondreferencestoenvironmentalprotectionandadaptationtoaddresssourcesofdisplacement(IGAD,2012).However,morerecentlya2020IGADProtocolonFreeMovementofPersonsallowsentryandstayinthecontextofdisastersandrecognisesthepositivecontributionoffreemovementinmitigatingimpactsassociatedwithdisasters,climatechangeandenvironmentaldegradation.Thiswasadoptedin2020andisnotyetratifiedatthetimeofwriting.Last,whileECOWAS’CommonApproachonMigrationrecognisestherightsofECOWAScitizenstoenter,reside,andsettleinmemberstates(ECOWAS,2008),itincludesnospecificreferencetotheenvironmentorclimate.Moreover,itsimplementationhasbeenhinderedbyalackofstandardisedlegislation,weakinstitutionalframeworks,andrestrictivenationalpolicies(Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016).Regionalclimatepoliciestendtoframemigrationmainlyasaproblemtobecontrolled(Chazalnoëletal.,2016).TheAU’sDraftClimateChangeStrategyframesclimate-relatedforceddisplacementandinternalandinternationalmigrationasan‘additionalburden’ofclimatechange,anddiscusseseffortsto‘stemandevenreverse’7.Policyframeworksandresponses55Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossrural-to-urbanmigration.(AU,2020).23IGAD’sDroughtDisasterResilienceandSustainabilityInitiativeStrategyidentifiesenvironmentalchangeandclimaticvariationsascontributorstopopulationdisplacementand‘climaterefugees’andidentifiesbothdisplacementandrural-to-urbanmigrationassocioeconomicrisks(IDDRSI,2013).ManyNAPAsandotherpoliciesacrosstheSahelframecross-bordermigration,includingtranshumance,asapotentialproblem,linkedtocompetitionoverlandandwater,conflictandinstability,andenvironmentaldamage(Opitz-Stapletonetal.,2021).MaliReflectingregionaltrends,Mali’sclimateanddevelopmentpoliciesframeenvironmentalmigrationprimarilyasaproblemtobecontrolledorprevented,ordonotmentiontheissuealtogether:—DespiteMali’s2007NationalAdaptationPlanofAction(NAPA)recognisingmigrationasanadaptationstrategyinthefaceofenvironmentalrisksandnewclimaticconditions,especiallydroughtsintheInnerNigerDelta,itidentifiesascoreaimsthe‘sedentarisation’ofpopulationsandthereductionofmigration(Ministèredel’EquipementetdesTransport,2007).—Mali’s2011NationalPolicyonClimateChangeincludesnoexplicitmentionofmigrationormobility,apartfromthefactthatclimaticvariabilityhasstronglyaffectedherdinglivelihoods,drivingmovementstowardMali’ssouthandresultinginconflictsbetweenherdersand23TheAfricanUnionClimateChangeandResilientDevelopmentStrategyandActionPlanwasadoptedbyAUHeadsofStateandgovernmentinFebruary2022.farmers(Ministèredel’Environnement,2011).—Mali’s2013AgriculturalDevelopmentPolicyidentifiesasanaxisofinterventionthedevelopmentofclimatechangeadaptationmechanisms,includingthroughstrengtheningcapacitiesofvulnerableruralpopulations,andhighlightstheneedforsustainablenaturalandenvironmentalresourcemanagementinacontextofclimatechange(RépubliqueduMali,2013).However,itdoesnotmentionmigrationasanadaptationstrategy.—PovertyReductionStrategyPapers(PRSPs)inMalihaveintegratedenvironmentalissuesascross-cuttingthemes,suggestingthatruraldevelopmentinitiativesconstituteimportantmeanstopreventrural-to-urbanmigration(Hummel,2016;Liehretal.,2016).—Mali’s2015IntendedNationallyDeterminedContribution(INDC)planincludesnomentionofmigration(RépubliqueduMali,2015),nordoesitsRevisedNDC(Ministèredel’Environnement,2021).—Mali’s2018thirdNationalCommunicationtotheUNFrameworkConventiononClimateChange(UNFCCC)onlymentionstranshumanceinrelationtomigration,pointingoutthatthecountryreceivestranshumanceherdersfromNiger,BurkinaFasoandMauritania.56Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossSudanClimate-andenvironment-relatedmigrationisnotprominentinnationalpolicies,inthecontextofrecentpoliticalchanges.Evenbeforethepoliticalcrisisin2021,migrationpolicieswerefocusedondisplacementcausedbyconflictandviolence,especiallyinDarfurandfromEthiopiaandSouthSudan.TheNationalCouncilforStrategicPlanningGeneralSecretariat’sTwenty-Five-YearNationalStrategy2007—2031makesthisexplicit,includingmigrationandinternalmovementasasecurityanddefencethreattogetherwithethnicandregionalviolenceandconflict,andmentioningtheneedto‘settlenomads.’Thecurrentgovernmentapproachtomigrationfocusesonbordercontrolanddevelopingthecapacityoflawenforcement,aswellasthehealthandsocialsectorstosomeextent.InWhiteNile,RedSea,KassalaandNorthernstates,amigrationtechnicalcommitteeisworkingonmigration,focusingondisplacementandonthelawenforcementperspective.Sudan’sclimateanddevelopmentpoliciesalsoframemigration(bothinternalandcross-border)inresponsetoclimate-relatedpressuresasproblematicandsomethingtobecontrolled(Chazalnoëletal.,2016):—The2016NAPAidentifiesmigrationasasignificant‘adverseimpact’ofclimatechange,referringtomovementduetoflooding,desertification,andresourcedegradationaswellaspotentialclimate-induceddisplacementtowardareaslessvulnerabletodroughts.Thedocumentalsomentionsthatdecreasingagriculturalproductivityinotherregionsmayalsoleadtoaninfluxofclimaterefugeesandtheout-migrationofpastoralists,andinturntotheneedtodevelopinstitutionalandinfrastructurecapacitytoaccommodatethis(MinistryofEnvironment,2016).—TheNationalPlanfortheimplementationoftheGreatGreenWallfortheSahelandSahararecognisestheinteractionofhumanactivitiesandclimatedriversinaffectingmobility.Itacknowledgesthatlarge-scalemechanisedfarmingisblockingtranshumantnomadicroutesbydecreasinggrazingareas,andthatclimaticconditionsareexacerbatingthis.—Sudan’s2015IntendedNationallyDeterminedContribution(INDC)planidentifieshumandisplacementasa‘keyvulnerability’linkedtoclimatechangeandproposeswater-relateddevelopmentstodiscouragemigrationfromvulnerableareas(RepublicofSudan,2015).Sudan’supdatedNDCsubmissionincludesnomentionofmigration(HighCouncilforEnvironment,2021).—Sudan’s2021PovertyReductionStrategyPaperdescribesadverseconsequencesofenvironmentaldegradationandclimatechangeascontributingtoorcompoundingpoverty,especiallyinruralareas,andidentifiesasaprioritystrengtheningresilienceofcommunitiesinthefaceofclimatechange.Whilenomentionismadeofmigrationspecificallyinrelationtoclimate,anaimoftheStrategy’sagriculturaldevelopmentcomponentisto‘discouragemigration’(MinistryofFinance,2021).57Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTheserecommendationsemergefromthefindingsandincludesuggestionsfromFGDparticipantsandintervieweesinMaliandSudan,aswellasintervieweesinthewiderSahel,whowereaskedtoidentifythetypesofassistancethatwouldbenecessarytosupportcopingandadaptationresponses,includinginrelationtomobility.8.1Recommendationsfornationalandinternationalhumanitarianactors(includingNationalRedCrossandRedCrescentSocieties)Ensurethatprogrammaticaction,organisationalnarrativesand(throughhumanitariandiplomacy)policyframeworksacknowledgeandreflectthecomplexrelationshipbetweenclimatechangeandmobility:—Strengthenengagementwithexistingevidenceonclimatechangeandmigration.Manyofthekeyfindingspresentedinthisreportchallengecommonorganisationalorpolicynarrativesthatoftenpresentasimplisticrelationshipbetweenclimatechangeandmigration(althoughthereasonsforsuchnarratives,includinginrelationtoadvocacy,mustbeacknowledged).Thishighlightstheimportanceofdrawingonexistingacademicandexpertresearchfindingsonclimatechange-migrationrelationshipstoinformcommunicationsandadvocacystrategies,andstrategicplansonclimatechangeandmigration,toensurethesereflectandareadjustingtoemergingevidence.—Giventhetransbordernatureofclimatechangeanditsimpacts,thereisaneedformoresystematicdialogueandcoordinationbetweenactorsworkingindifferentcountries,forexamplebetweendifferentNationalRedCrossandRedCrescentSocieties,andbetweenregionsofthesamecountry,toinformunderstandingofthevulnerabilitiesandneedsassociatedwithclimate-relatedmigrationinitslocalisedandtransborderdimensionsaswellasinformingthedevelopmentofregionalstrategiesandcapacities.Addressvulnerabilitiesassociatedwithclimatechangeandmobility:—Targetandstrengthenroute-basedhumanitarianassistanceand(re)integrationsupporttopeoplewhomigrateinternallyandregionallyinresponsetoclimate-relatedandenvironmentalhazardsandchanges.Toincreasewellbeingandsocio-economicoutcomesintransitandindestinationlocalities,formsofassistancemightincludeassistanceinsecuringfoodandhousing,accesstohealthcareandotherbasicservices,informationonaccessingrequireddocumentation(e.g.workpermits),jobtraining,psychosocialandpsychologicalsupport,andfacilitatingcommunicationwithfamilymembers.Thisshouldbeembeddedinwiderworktoaddressexistingvulnerabilitiesamongmigrantpopulations,andoughttoinvolvearangeofactors,fromNGOstogovernmentstohostcommunities.—Ensurethatsupportforadaptationandtomeetneedsamongvulnerablemigrantstakesintoaccountthedifferentialeffectsofenvironmentalandclimatechangeonvulnerabilityandmobility,alonglinesofgender,age,disability,livelihoodtype,andincome.Responsesshouldexplicitlyconsider8.Recommendations58Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrosstheneedsofgroupsthatareparticularlyvulnerabletotheadverseeffectsofclimatechange,andthosewhofacebarrierstomobility.Giventheunevenimpactsofenvironmentalchange,associatedmigrationpressuresandunevenaccesstoadaptationoptions(includingmobility),supportforin-placecopingandadaptationstrategiesshouldbetargetedto(andinformedbytheprioritiesof)groupssuchasolderadults,youngpeople,women,peoplewithdisabilities,farmers,herders,orfishers.Supportgovernmentstostrengthenthedevelopmentandimplementationoflawsandpoliciesaddressingclimate-relatedmobility(seeSection8.2),throughpolicyengagementandhumanitariandiplomacy.Forexample,NationalRedCrossandRedCrescentSocietiescanincreaseengagementwithnationalgovernmentsonthis,buildingontheirroleashumanitarianauxiliariestonationalauthorities,aswellasglobaleffortsbytheInternationalRedCrossandRedCrescentMovementtoaddresswiderassistanceandprotectionneedsofpeopleonthemove.—Advancepartnershipstoaddressgapsintheevidencebaseinordertobettermeetneedsforsupport.Inthisrespect,NationalRedCrossandRedCrescentSocietieshaveauniqueroletoplayinassessingconditionsontheground.Thisresearchpointstoaspectsofpatternsofclimate-relatedmobilityonwhichthereiscurrentlyadearthofinformation.Forexample:internalmigrantsworkinginartisanalgoldminesinSudanandthewiderSahel;peoplewhomigrateasanadaptivestrategybutwishtoreturntoliveintheirlocalityoforigin;orpeoplewhoaredisplacedmultipletimesduetothesameclimate-relatedhazard.Eachofthesegroupshavedifferentvulnerabilities,needsandaspirationsthatwillrequirespecificsupport.Inthisrespect,collaborativeworkingacrossdifferenthumanitariananddevelopmentorganisations,includingNationalRedCrossandRedCrescentSocieties,iscriticaltoincreasethespecificityofsupport.Supportadaptationandcommunityresiliencestrategieswithinclimate-vulnerablecommunities,sothatmobilityremainsachoicebutisnottheonlyoption:—Expandcommunityknowledgeofandaccesstoearlywarningsystemsandclimateinformation,tosupportpreparednessandearlyandanticipatoryactioninresponsetoclimate-relatedhazards,buildingongovernmentpartnershipsandexistingmechanisms(e.g.radiobroadcasts,volunteernetworks)toshareinformationandalertsandtoinformpeople’santicipatory,adaptative,andmobilitydecisions.—Ensurethatsupportgoesbeyondshort-termneedsbystrengtheningmaterialsupportforlonger-termcopingandlocally-ledadaptationinitiatives,guidedbylocally-determinedneedsandstrategies.Forexample,throughskillstrainingandprovisionofmaterialresources(e.g.fundsandequipmenttosupportlivelihooddiversification,agriculturalinnovations,etc.),targetingallthoseinneedofsupportregardlessoftheirintentionsorabilitytomigrate.—Ensurethatsupportisprovidedbasedonanunderstandingofthekeybarrierstoadaptationinspecific59Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrosscommunitiesandtheneedsofdifferentgroups.Forexample,ensuringthatsupportgoesbeyondcopingstrategiesandadaptationinterventionsintheagriculturalsectortorespondtothevariedaspirationsofyoungpeople,whomaynotwishtoworkinagriculture.8.2Recommendationsfornationalgovernmentsandregionalorganisations—Promotetheconsistentintegrationofclimate-relatedmobility,includingdisplacementandmigration,intorelevantnationalandregionalpolicyandlegalframeworksandstrategies,includingclimateadaptationplans,disasterriskreductionandresponseplans,povertyreductionandotherdevelopmentplans,andmigrationandsettlementpolicies.Responsesshouldbebasedonexistingevidence,shoulddrawontheneedsandprioritiesofaffectedcommunities,andshouldinvolvetheparticipationofNationalRedCrossandRedCrescentSocietyrepresentativesalongsidecivilsocietyandgovernmentactors.—Recognisemigrationinresponsetoclimatevulnerabilitiesasaformofadaptationandasinvolvingrisksandlosses,ratherthanasaproblemtobemanagedandprevented.Atthesametime,migrationshouldnotbeconsideredasafeasiblesolutionorpanaceatoclimate-relatedchallengesunderallcircumstances,giventhechallengesandsocialandmateriallossesthatmaybeassociatedwithmobility.Furthermore,non-migrationshouldnotbeequatedwithadaptation,giventhatmanypeoplemaybe‘trapped’insituationsofextremevulnerability.—Avoidlookingatclimate-relatedmobilityinisolation,butrathersituateitwithinthecontextofthebroaderdynamicsofenvironmentalchangethatunderpinclimate-relatedvulnerabilitiesandmigrationpressures.Thisinvolvesexplicitlyconsideringthesocioeconomicandpoliticalbarriers(andinequalitiesinaccess)tofinancialsupport,waterandagriculturalinputs;restrictionsonaccesstolandandwatersources;andalackofclearlandtenureandlegalrights;allofwhichcontributetoexistingsocioeconomicvulnerabilitiesandmayintensifytheimpactsofclimatechangeandassociatedmigrationpressureswhilelimitingpossibilitiesforcopingandadaptation.—Expandknowledgeofandaccesstoearlywarningsystemsandclimateinformationtosupportpreparednessandearlyandanticipatoryactioninresponsetoclimate-relatedhazardsthroughregionalandnationalmeteorologicalagencies.—Addresselementsofpolicyframeworksthatcreateorexacerbatevulnerabilitiesamongpeopleonthemoveingeneral,thatmayimpactindividualsmovinginresponsetoclimate-relatedandenvironmentalchanges.Thisinvolvesaddressingbarrierstoobtainingresidentandworkpermits,healthcareandeducationservices,housing,andemployment.60Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCross8.3Recommendationsforinternationaldonors—Investinbuildinganevidencebasetoimproveunderstandingofhowclimatechangeinteractswithexistingandfuturepatternsanddriversofmobilityinspecificcontexts,inordertoanticipatefutureimpactsandtosupportresilienceandadaptationstrategieswithinclimate-vulnerablecommunities.—Addressvulnerabilitiesassociatedwithclimatechangeandmobility,includingthroughinvestmentinaddressingtheimpactsofclimatechangeonhumanitarianneedsbothformigrantsandforpeopleremaininginplace.Intermsofaddressinghumanitarianneedsinthecontextofmigration,thisshouldinvolveconsiderationofclimate-relatedmigration,aspartofwiderflexible,needs-basedandsustainablefundingforinternationalhumanitarianassistanceandprotectiontomigrantsinsituationsofvulnerability.Supportforpeoplewhowishtoremaininplacemightinvolvetheprovisionofflexibleandaccessibleclimateadaptationfinancefornationalandinternationalorganisationstoaddressimmediatehumanitarianvulnerabilitieslinkedtoclimate-relatedmobilityalongsidepreparednessmeasuressuchasearlywarningsystemsandin-placecoping,adaptation,andresiliencemeasures.—Ensurethatfundingtoaddressvulnerabilitiesassociatedwithclimate-relatedmigration,aswellasfundingthattargetswidervulnerabilitiesamongmigrants,focusesonallmigrantsinsituationsofvulnerability.Thisincludesattentiontointernalandintra-regionalmovement,ratherthananemphasisonpreventing‘irregular’migrationtowardsEurope.—Supportinternationalacknowledgementandconsensusthatmobilitycanbeanimportantadaptationstrategytobeenabledamongarangeofchoicesforpeopleinclimate-vulnerablecommunities.61Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossAbdi,O.A.,Glover,E.K.,andLuukkanen,O.(2013)Causesandimpactsoflanddegradationanddesertification:casestudyoftheSudan.InternationalJournalofAgricultureandForestry,3(2),40–51.AdvisoryGrouponClimateChangeandHumanMobility.(2015)Humanmobilityinthecontextofclimatechange:elementsfortheUNFCCCParisAgreement.AdvisoryGrouponClimateChangeandHumanMobility.Afifi,T.,Govil,R.,Sakdapolrak,P.andWarner,K.(2012)Climatechange,vulnerabilityandhumanmobility:perspectivesofrefugeesfromtheEastandHornofAfrica.Bonn:UNU-EHS.AfricanUnion(AU)(2009)AfricanUnionConventionfortheProtectionandAssistanceofInternallyDisplacedPersonsinAfrica(KampalaConvention).AddisAbaba:AfricanUnion.AfricanUnion(2010)PolicyFrameworkforPastoralisminAfrica:Securing,ProtectingandImprovingtheLives,LivelihoodsandRightsofPastoralistCommunities.AddisAbaba:DepartmentofRuralEconomyandAgriculture,AfricanUnion.AfricanUnion(2018a)MigrationPolicyFrameworkforAfricaandPlanofAction(2018–2030).AddisAbaba:AfricanUnion.AfricanUnion(2018b)ProtocoltotheTreatyEstablishingtheAfricanEconomicCommunityRelatingtoFreeMovementofPersons,RightofResidenceandRightofEstablishment.AddisAbaba:AfricanUnion.AfricanUnion(2020)DraftAfricaClimateChangeStrategy2020–2030.AddisAbaba:AfricanUnion.Alou,M.T.,Maïga,I.M.andHainikoye,A.D.(2015)AucoeurdelamarginalisationdesfemmesenmilieururalNigérien:l’accèsàl’eauagricole.LesCahiersd’Outre-Mer,68(270),163–188.Anderson,K.,Golovko,E.andHargrave,K.(2021)Risksandresilience:exploringmigrants’andhostcommunities’experiencesduringtheCOVID-19pandemicinWestAfrica.Geneva:InternationalFederationofRedCrossandRedCrescentSocieties.Barros,D.D.(2010)Liensville-villageetchangementssociauxfaceàlamigrationsaisonnière:lemouvementdepersonnesentreSongho(régiondogon)etBamakoMali.Anthropos,471–488.Bello,I.M.(2016)LesstratégiesdegestionderisquesagricolesauNiger:évidenceempiriqueetimplicationpourlesménagesagricoles.ÉconomieRurale:Agricultures,Alimentations,Territoires,351,67–78Benjaminsen,T.A.,Aune,J.B.andSidibé,D.(2010)AcriticalpoliticalecologyofcottonandsoilfertilityinMali.Geoforum,41,647–656.9.References62Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossBertoli,S.,Docquier,F.,Rapoport,H.andRuyssen,I.(2020)WeathershocksandmigrationintentionsinWesternAfrica:insightsfromamultilevelanalysis.Munich:CenterforEconomicStudiesandIfoInstitute.Bizoza,A.R.(2019)LandrightsandeconomicresilienceofruralwomenintheG5-Sahelcountries,WestAfrica.AfricanJournalonLandPolicyandGeospatialSciences,2(1),46–59.Bleck,J.andLodermeier,A.(2020)Migrationaspirationsfromayouthperspective:focusgroupswithreturneesandyouthinMali.TheJournalofModernAfricanStudies,58(4),551–577.Bluett,K.andDavy,D.(2020)AccesstoessentialservicesforpeopleonthemoveintheECOWASregion.StudycommissionedbytheInternationalFederationofRedCrossandRedCrescentSocietiesandtheUnitedNationsHighCommissionerforRefugees.Bonnet,B,andGuibert,B.(2014)Stratégiesd’adaptationauxvulnérabilitésdupastoralisme:trajectoiresdefamillesdepasteurs(1972–2010).AfriqueContemporaine,1(249),37–51.Borderon,M.,Sakdapolrak,P.,Muttarak,R.,etal.(2019)MigrationinfluencedbyenvironmentalchangeinAfrica:asystematicreviewofempiricalevidence.DemographicResearch,41,491–544.Bouaré-Trianneau,K.N.(2013)Lerizetlebœuf,agro-pastoralismeetpartagedel’espacedansleDeltaintérieurduNiger(Mali).LesCahiersd’Outre-Mer,66(264),423–444.BritishRedCross(2022)Fromcommitmentstoreality:BritishRedCrosshumanitarianprioritiesfortheInternationalMigrationReviewForum.London:BritishRedCross.Brockhaus,M.,Djoudi,H.andLocatelli,B.(2013)Envisioningthefutureandlearningfromthepast:adaptingtoachangingenvironmentinnorthernMali.EnvironmentalScienceandPolicy,25,94–106.Chazalnoël,M.,Mach,E.andIonesco,D.(2016)MigrationintheIntendedNationallyDeterminedContributions(INDCs)andNationallyDeterminedContributions(NDCs).Geneva:IOM.Corner,A.,Shaw,C.andClarke,J.,(2018)Principlesforeffectivecommunicationandpublicengagementonclimatechange:AHandbookforIPCCauthors.[online]Oxford:ClimateOutreach.Availableat:ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2017/08/Climate-Outreach-IPCC-communications-handbook.pdf[Accessed13May2022].Daouda,Y.H.(2015)LespolitiquespubliquesagricolesauNigerfaceauxdéfisalimentairesetenvironnementaux:entreéchecsrépétitifsetnouvellesespérances.LesCahiersd’Outre‑Mer,68(270),115–136.63Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossDaum,C.(2014)Entreindividualisationetresponsabilitésfamiliales:lesmobilitésdesjeunesdelarégiondeKayesauMaliDefrance,D.,Delasalle,E.andGubert,F.(2020)Ismigrationdrought-inducedinMali?AnempiricalanalysisusingpaneldataonMalianlocalitiesoverthe1987–2009period.Paris:UMRLEDa.DeLongueville,F.,Ozer,P.,Gemenne,F.,etal.(2020)ComparingclimatechangeperceptionsandmeteorologicaldatainruralWestAfricatoimprovetheunderstandingofhouseholddecisionstomigrate.ClimaticChange,160(1),123–141.DeLongueville,F.,Zhu,Y.andHenry,S.(2019)DirectandindirectimpactsofenvironmentalfactorsonmigrationinBurkinaFaso:applicationofstructuralequationmodelling.PopulationandEnvironment,40(4),456–479.Deubel,T.andBoyer,M.(2017)Gender,marketsandwomen’sempowermentintheSahelregion:acomparativeanalysisofMali,Niger,andChad.Dakar:WorldFoodProgramme.Diallo,A.,Donkor,E.,andOwusu,V.(2020)Climatechangeadaptationstrategies,productivityandsustainablefoodsecurityinsouthernMali.ClimaticChange,159(3),309–327.Dillon,A.,Mueller,V.andSalau,S.(2011)MigratoryresponsestoagriculturalriskinNorthernNigeria.AmericanJournalofAgriculturalEconomics,93(4),1048–1061.Djoudi,H.andBrockhaus,M.(2011)Isadaptationtoclimatechangegenderneutral?LessonsfromcommunitiesdependentonlivestockandforestsinnorthernMali.InternationalForestryReview,13(2),123–135.Djoudi,H.,Brockhaus,M.andLocatelli,B.(2013)Oncetherewasalake:vulnerabilitytoenvironmentalchangesinnorthernMali.RegionalEnvironmentalChange,13(3),493–508.Doka,M.D.,Magoudou,D.andDiouf,A.(2014)Foodcrisis,gender,andresilienceintheSahel:lessonsfromthe2012crisisinBurkinaFaso,Mali,andNiger.Oxford:OxfamGB.Doso,S.(2014)LanddegradationandagricultureintheSahelofAfrica:causes,impactsandrecommendations.JournalofAgriculturalScienceandApplications,3(3),67–73.Drees,L.,andLiehr,S.(2015)UsingBayesianbeliefnetworkstoanalysesocial-ecologicalconditionsformigrationintheSahel.GlobalEnvironmentalChange,35,323–339.Ebi,K.L.,Padgham,J.,Doumbia,M.,etal.(2011)SmallholdersadaptationtoclimatechangeinMali.ClimaticChange,108(3),423–436.64Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossECOWAS(2003)RegulationC/REG.3/01/03relatingtotheimplementationoftheregulationsontranshumancebetweentheECOWASmemberstates.Dakar:ECOWAS.ECOWAS(2008)ECOWASCommonApproachonMigration.Ouagadougou:ECOWASCommission.Eizenga,D.(2019)LongtermtrendsacrosssecurityanddevelopmentintheSahel.Paris:OECDPublishing.Elagib,N.A.(2011)Changingrainfall,seasonalityanderosivityinthehyper‐aridzoneofSudan.LandDegradationandDevelopment,22(6),505–512.Elagib,N.A.,AlZayed,I.S.,Saad,S.A.G.,etal.(2021)DebilitatingfloodsintheSahelarebecomingfrequent.JournalofHydrology,599,126362.ElTahir,B.A.,MohammedFadl,K.E.,andFadlalmula,A.G.D.(2010)ForestbiodiversityinKordofanRegion,Sudan:Effectsofclimatechange,pests,diseaseandhumanactivity.Biodiversity,11(3–4),34–44.Epule,T.E.,Ford,J.D.,Lwasa,S.andLepage,L.(2017)ClimatechangeadaptationintheSahel.EnvironmentalScienceandPolicy,75,121–137.Etana,D.,Snelder,D.,Wesenbeeck,C.andBuning,T.(2020)Climatechange,in-situadaptation,andmigrationdecisionsofsmallholderfarmersincentralEthiopia.MigrationandDevelopment.FoodandAgricultureOrganization(FAO)(2019)Sahelregionaloverview:December2019.Rome:FAO.Generoso,R.(2015)Howdorainfallvariability,foodsecurityandremittancesinteract?ThecaseofruralMali.EcologicalEconomics,114,188–198Grace,K.,Hertrich,V.,Singare,D.,andHusak,G.(2018)ExaminingruralSahelianout-migrationinthecontextofclimatechange:ananalysisofthelinkagesbetweenrainfallandout-migrationintwoMalianvillagesfrom1981to2009.WorldDevelopment,109,187–196.Gray,C.andMueller,V.(2012)DroughtandpopulationmobilityinruralEthiopia.WorldDevelopment,40(1),134–45.Gray,C.andWise,E.(2016)Country-specificeffectsofclimatevariabilityonhumanmigration,ClimaticChange,135(3–4),555–568.Groth,J.,Ide,T.,Sakdapolrak,P.,etal.(2020)Decipheringinterwovendriversofenvironment-relatedmigration:amultisitecasestudyfromtheEthiopianhighlands.GlobalEnvironmentalChange,63,102094.Gubert,F.,Lassourd,T.andMesplé-Somps,S.(2010)Doremittancesaffectpovertyandinequality?EvidencefromMali.Paris:IRDandParisSchoolofEconomics.65Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossHalimatou,A.T.,Kalifa,T.,andKyei-Baffour,N.(2017)AssessmentofchangingtrendsofdailyprecipitationandtemperatureextremesinBamakoandSégouinMalifrom1961–2014.WeatherandClimateExtremes,18,8–16.Hamadalnel,M.,Zhu,Z.,Lu,R.,etal.(2021)Spatio-temporalinvestigationsofmonsoonprecipitationanditshistoricalandfuturetrendoverSudan.EarthSystemsandEnvironment,5(3),519–529.Hermans,K.andGarbe,L.(2019)Droughts,livelihoods,andhumanmigrationinnorthernEthiopia.RegionalEnvironmentalChange,19(4),1101–11.Hiernaux,P.,Diawara,M.andGangneron,F.(2014)QuelleaccessibilitéauxressourcespastoralesduSahel?L’élevagefaceauxvariationsclimatiquesetauxévolutionsdessociétéssahéliennes.AfriqueContemporaine,249,21–35.Hiernaux,P.,Mougin,E.,Diarra,L.,etal.(2009)SahelianrangelandresponsetochangesinrainfallovertwodecadesintheGourmaregion,Mali.JournalofHydrology,375(1–2),114–127.Hoffmann,R.,Dimitrova,A.,Muttarak,R.,etal.(2020)Ameta-analysisofcountry-levelstudiesonenvironmentalchangeandmigration.NatureClimateChange,10(10),904–912.Holmes,S.,Brooks,N.,Daoust,G.,etal.(2022)ClimateriskreportfortheSahelregion.London:MetOffice,ODI,andFCDO.Hoogeveen,J.G.,Rossi,M.andSansone,D.(2019)Leaving,stayingorcomingback?MigrationdecisionsduringthenorthernMaliconflict.TheJournalofDevelopmentStudies,55(10),2089–2105.Hummel,D.(2016)Climatechange,landdegradationandmigrationinMaliandSenegal:somepolicyimplications.MigrationandDevelopment,5(2),211–233.Ibnouf,F.O.(2011)ChallengesandpossibilitiesforachievinghouseholdfoodsecurityinthewesternSudanregion:theroleoffemalefarmers.FoodSecurity,3(2),215–231.Ickowicz,A.,Ancey,V.,Corniaux,C.,etal.(2012)Crop-livestockproductionsystemsintheSahel:increasingresilienceforadaptationtoclimatechangeandpreservingfoodsecurity.InA.Meybecketal.(eds)BuildingResilienceforAdaptationtoClimateChangeintheAgricultureSector(261–294).Rome:FAO.InternationalFederationofRedCrossandRedCrescentSocieties(IFRC)(2021a)Displacementinachangingclimate:localizedhumanitarianactionattheforefrontoftheclimatecrisis.Geneva:IFRC.IFRC,(2017)IFRCGlobalStrategyonMigration2018–2022–ReducingVulnerability,EnhancingResilience.[online]Geneva,Switzerland:InternationalFederationofRedCrossandRedCrescentSocieties.Availableat:https://www.ifrc.org/document/ifrc-strategy-migration-1[Accessed7Jun.2022].66Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossIFRC(2021b)Humanitarianassistanceandprotectionforpeopleonthemove:aroute-basedapproachspanningAfrica,MiddleEastandEurope.Geneva:IFRC.Ihring,D.andMeskers,J.(2021)TheimpactoftheSahelconflictoncross-bordermovementsfromBurkinaFasoandMalitowardsCôted’IvoireandGhana.MixedMigrationCentre.Inter-GovernmentalAuthorityonDevelopment(IGAD)(2012)IGADRegionalMigrationPolicyFramework.AddisAbaba:Inter-GovernmentalAuthorityonDevelopment.IGADDroughtDisasterResilienceandSustainabilityInitiative(IDDRSI)(2013)TheIDDRSIStrategy.Djibouti:IGAD.InternalDisplacementMonitoringCentre(IDMC)(2021)GlobalReportonInternalDisplacement2021:internaldisplacementinachangingclimate.Geneva:IDMC.InternationalOrganizationforMigration(IOM)(2022a)‘Keymigrationterms’,iom.int/key-migration-termsIOM(2022b)‘Migrationdataportal’,migrationdataportal.org/international-dataIntergovernmentalPanelonClimateChange(IPCC)(2022)Summaryforpolicymakers.InH.-O.Pörtner,D.C.Roberts,M.Tignor,etal.(eds.),ClimateChange2022:Impacts,Adaptation,andVulnerability.ContributionofWorkingGroupIItotheSixthAssessmentReportoftheIntergovernmentalPanelonClimateChange.CambridgeUniversityPress.Kiema,A.,Tontibomma,G.andZampaligré,N.(2014)TranshumanceetgestiondesressourcesnaturellesauSahel:contraintesetperspectivesfaceauxmutationsdessystèmesdeproductionspastorales.VertigO,14(3).Kirwin,M.andAnderson,J.(2018)IdentifyingthefactorsdrivingWestAfricanmigration.Paris:OECD.Konaté,F.O.(2010)LamigrationfémininedanslavilledeKayesauMali.HommesetMigrations,4(1286–1287),62–73.Koutou,M.,Sangaré,M.,Havard,M.,etal.(2016)Adaptationdespratiquesd’élevagedesproducteursdel’OuestduBurkinaFasofaceauxcontraintesfoncièresetsanitaires.AgronomieAfricaine,28(2),13–24.Liehr,S.,Drees,L.andHummel,D.(2016)MigrationassocietalresponsetoclimatechangeandlanddegradationinMaliandSenegal.InJ.A.YaroandJ.Hesselberg(eds.),AdaptationtoClimateChangeandVariabilityinRuralWestAfrica(147–169).Cham:Springer.Lind,J.,Sabates-Wheeler,R.,Caravani,M.,etal.(2020)Newlyevolvingpastoralandagro-pastoralrangelandsofEasternAfrica.Pastoralism:Research,PolicyandPractice,10,24.Lombard,J.(2008)Kayes,villeouverte:migrationsinternationalesettransportsdansl’ouestduMali.Autrepart,3(47),91–107.Marega,O.andMering,C.(2018)Lesagropasteurssahéliensfaceauxchangementssocio-environnementaux:nouveauxenjeux,nouveauxrisques,nouveauxaxesdetranshumance.L’EspaceGéographique,47(3),235–260.67Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossMcCullough,A.,Mayhew,L.,Opitz-Stapleton,S.etal.(2019)Whenrisingtemperaturesdon’tleadtorisingtempers:climateandinsecurityinNiger.London:ODI.Ministèredel’Environnementetdel’Assainissement(2011)PolitiqueNationalesurlesChangementsClimatiques.Bamako:Ministèredel’Environnementetdel’Assainissement,RépubliqueduMali.Ministèredel’Environnement,del’AssainissementetduDéveloppementDurable(2021)ContributionDéterminéeauNiveauNationalRévisée.Bamako:Ministèredel’Environnement,del’AssainissementetduDéveloppementDurable,RépubliqueduMali.Ministèredel’EquipementetdesTransports(2007)Programmed’ActionNationald’AdaptationauxChangementsClimatiques.Bamako:Ministèredel’EquipementetdesTransports,RépubliqueduMali.MinistryofEnvironment,NaturalResourcesandPhysicalDevelopment(2016)NationalAdaptationPlan.Khartoum:MinistryofEnvironment,NaturalResourcesandPhysicalDevelopment,RepublicoftheSudan.MinistryofFinanceandEconomicPlanning(2021)SudanPovertyReductionStrategyPaper2021–2023.Khartoum:MinistryofFinanceandEconomicPlanning,RepublicofSudan.Mokhnacheva,D.(2022)BaselineMappingoftheImplementationofCommitmentsrelatedtoAddressingHumanMobilityChallengesintheContextofDisasters,ClimateChangeandEnvironmentalDegradationundertheGlobalCompactforSafe,OrderlyandRegularMigration(GCM).Geneva:PlatformonDisasterDisplacement.Morrissey,J.W.(2013)Understandingtherelationshipbetweenenvironmentalchangeandmigration:thedevelopmentofaneffectsframeworkbasedonthecaseofnorthernEthiopia.GlobalEnvironmentalChange,23(6),1501–10.Mueller,V.,Gray,C.andHopping,D.(2020a)Climate-inducedmigrationandunemploymentinmiddle-incomeAfrica.GlobalEnvironmentalChange,65,102183.Mueller,V.,Sheriff,G.,Dou,X.andGray,C.(2020b)TemporarymigrationandclimatevariationineasternAfrica.WorldDevelopment,126.Naess,L.O.,Selby,J.andDaoust,G.(2022)Climateresilienceandsocialassistanceinfragileandconflict-affectedsettings.BASICResearchWorkingPaper2.Brighton:InstituteofDevelopmentStudies.Nawrotzki,R.J.andBakhtsiyarava,M.(2017)Internationalclimatemigration:evidencefortheclimateinhibitormechanismandtheagriculturalpathway.Population,SpaceandPlace,23(4).Nawrotzki,R.J.,Schlak,A.M.andKugler,T.A.(2016)Climate,migration,andthelocalfoodsecuritycontext:introducingTerraPopulus.PopulationandEnvironment,38(2),164–184.Ng’ang’a,S.K.,Bulte,E.H.,Giller,K.E.,etal.(2016)Migrationandself-protectionagainstclimatechange:acasestudyofSamburuCounty,Kenya.WorldDevelopment,84,55–68.68Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossNilsson,E.,Becker,P.andUvo,C.B.(2020)DriversofabruptandgradualchangesinagriculturalsystemsinChad.RegionalEnvironmentalChange,20(3),1–17.OECD/SWAC(2014)AnAtlasoftheSahara-Sahel:geography,economicsandsecurity.Paris:OECD/SahelandWestAfricaClub.OECD/SWAC(2020)Africa’surbanisationdynamics2020:Africapolis,mappinganewurbangeography.Paris:OECD/SahelandWestAfricaClub.OfficeoftheUNHighCommissionerforHumanRights(OHCHR)(2021)Humanrights,climatechangeandmigrationintheSahel.Geneva:OHCHR.Opitz-Stapleton,S.,Cramer,L.,Kaba,F.,etal.(2021)TransboundaryclimateandadaptationrisksinAfrica:perceptionsfrom2021.SupportingPastoralismandAgricultureinRecurrentandProtractedCrises(SPARC).Opitz-Stapleton,S.,Nadin,R.,Watson,C.andKellet,J.(2017)Climatechange,migrationanddisplacement:Theneedforarisk-informedandcoherentapproach.ODIandUNDP.Opondo,D.O.(2013)Erosivecopingafterthe2011floodsinKenya.InternationalJournalofGlobalWarming,5(4),452–66.Ouallet,A.(2008)Laquestionmigratoireetlesdynamiquestranssahariennesàtraversl’exemplemalien.AnnalesdeGéographie,5(663),82–103.Owain,E.L.andMaslin,M.A.(2018)Assessingtherelativecontributionofeconomic,politicalandenvironmentalfactorsonpastconflictandthedisplacementofpeopleinEastAfrica.PalgraveCommunications,4(1),1–9.Peters,K.,Dupar,M.,Opitz-Stapleton,S.,etal.(2020)Climatechange,conflictandfragility:anevidencereviewandrecommendationsforresearchandaction.London:ODI.Piguet,E.(2022).Linkingclimatechange,environmentaldegradation,andmigration:anupdateafter10years.WileyInterdisciplinaryReviews:ClimateChange,13(1),e746.RepublicofSudan(2015)IntendedNationallyDeterminedContributions(INDCs).Khartoum:RepublicofSudan.RépubliqueduMali(2013)PolitiquedeDéveloppementAgricoleduMali.Bamako:RépubliqueduMali.RépubliqueduMali(2015)ContributionPrévueDéterminéeauNiveauNational.Bamako:RépubliqueduMali.Richardson,K.,Calow,R.,Pichon,F.,etal.(2022)ClimateriskreportfortheEastAfricaregion.London:MetOffice,ODI,andFCDO.69Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossSauvain-Dugerdil,C.(2013)YouthmobilityinanisolatedSahelianpopulationofMali.TheAnnalsofTheAmericanAcademyofPoliticalandSocialScience,648(1),160–174.Scheffran,J.,Marmer,E.,andSow,P.(2012)Migrationasacontributiontoresilienceandinnovationinclimateadaptation:socialnetworksandco-developmentinNorthwestAfrica.AppliedGeography,33,119–127.Schwerdtle,P.N.,Stockemer,J.,Bowen,K.J.,etal(2020)Ameta-synthesisofpolicyrecommendationsregardinghumanmobilityinthecontextofclimatechange.InternationalJournalofEnvironmentalResearchandPublicHealth,17(24),9342.Selby,J.andDaoust,G.(2021)Rapidevidenceassessmentontheimpactsofclimatechangeonmigrationpatterns.London:Foreign,CommonwealthandDevelopmentOffice.Streiff-Fénart,J.andPoutignat,P.(2014)Vivresur,vivredelafrontière:l’aprèstransitenMauritanieetauMaliSulieman,H.M.(2013)LandgrabbingalonglivestockmigrationroutesinGadarifState,Sudan:impactsonpastoralismandtheenvironment.TheLandDealPoliticsInitiative.Sulieman,H.M.andElagib,N.A.(2012)Implicationsofclimate,land-useandland-coverchangesforpastoralismineasternSudan.JournalofAridEnvironments,85,132–141.Tarif,K.andGrand,A.O.(2021)‘ClimatechangeandviolentconflictinMali’,accord.org.za/analysis/climate-change-and-violent-conflict-in-maliTiitmamer,N.(2020)SouthSudan’sdevastatingfloods:whythereisaneedforurgentresiliencemeasures.Juba:SuddInstitute.Tiitmamer,N.(2021)AclimatecrisisinAfrica:thecaseofSouthSudan.TheCairoReviewofGlobalAffairs,thecairoreview.com/essays/a-climate-crisis-in-africa-the-case-of-south-sudanTraore,B.,Corbeels,M.,VanWijk,M.T.,etal.(2013)EffectsofclimatevariabilityandclimatechangeoncropproductioninsouthernMali.EuropeanJournalofAgronomy,49,115–125.Traore,B.,VanWijk,M.T.,Descheemaeker,K.,etal.(2015)ClimatevariabilityandchangeinsouthernMali:learningfromfarmerperceptionsandon-farmtrials.ExperimentalAgriculture,51(4),615–634.Trauner,F.andDeimel,S.(2013)TheimpactofEUmigrationpoliciesonAfricancountries:thecaseofMali.InternationalMigration,51(4),20–32.UNConventiontoCombatDesertification(UNCCD)(2020)TheGreatGreenWallimplementationstatusandwayaheadto2030.Bonn:UNCCD.70Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossvanderLand,V.andHummel,D.(2013)VulnerabilityandtheroleofeducationinenvironmentallyinducedmigrationinMaliandSenegal.EcologyandSociety,18(4).WorldBank(2021)‘WorldDevelopmentIndicatorsDataBank’.databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicatorsYoung,H.andIsmail,M.A.(2019)Complexity,continuityandchange:livelihoodresilienceintheDarfurregionofSudan.Disasters,43,S318–S344.Zickgraf,C.(2021).Climatechange,slowonseteventsandhumanmobility:reviewingtheevidence.CurrentOpinioninEnvironmentalSustainability,50,21–30.Zoma-Traoré,B.,Soudré,A.,Ouédraogo-Koné,S.,etal.(2020)Fromfarmerstolivestockkeepers:atypologyofcattleproductionsystemsinsouth-westernBurkinaFaso.TropicalAnimalHealthandProduction,52(4),2179–271Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossAppendix1.DatacollectionmethodsIn-countryresearchTheresearchinMaliandinSudanwasledbyin-countryresearchpartners.InMali,theresearchwasledbyKénéConseils,basedinBamako,andinSudan,theresearchwasledbytheDirectoroftheCentreforRemoteSensingandGISattheUniversityofGadarifandhisteam.VirtualplanningmeetingswereheldwiththeresearchersinMaliandinSudantoclarifyandrefinetheaimsofthestudy,themethodology,andkeyquestions.InMali,datacollectionwascarriedoutbyateamof10fieldresearchers,whoreceivedtrainingbytheleadin-countryresearchersontheaimsofthestudy,onthedatacollectiontools,andondatacollectiontechniquesandethics.SimilartrainingwasprovidedbythedirectoroftheCentreforRemoteSensingandGISattheUniversityofGadariftotheresearchteaminSudan.DatacollectionmethodsInMaliandSudan,datawascollectedthroughquantitativesurveysandqualitativefocusgroupsdiscussions(FGDs)andindividualinterviews.Thesurvey,FGD,andinterviewtoolsweredevelopedwithinputfromthein-countryresearchpartners.WhilecommontoolswereusedinbothMaliandSudan,in-countryresearchersadaptedquestionsinresponsetocontextualcircumstances.Thequantitativeandqualitativedatacollectioncomponentswereconductedsimultaneously.Quantitativesurveys.Quantitativedatawascollectedviaindividualsurveys.Purposivesamplingforthesurveystargetedbothmigrantsandmembersofsending,transitandreceivingcommunities,womenandmen,andyoungerandolderadults.InMali,100respondentstookpartinthesurvey,including50inBamakoand50inKayes.InBamako,surveydatawascollectedinfivecommunes:Communes1,2,4,5,and6.InKayes,surveydatawascollectedinninelocalities:HawaDembaya,LibertéDembaya,Kayes,Khouloum,Somankidi,SaméDiomgoma,Gouméra,GoryGopela,andBangassi.InSudan,165respondentstookpartinthesurvey,including50inElfaovillageinGadarif,60inElganaavillageinWhiteNileand55inDabatBosinrefugeecampinWhiteNile.InMali,thesurveywasimplementedinFrench,English,andinBamanankan,thelanguageusedbythemajorityofthepopulationinBamakodistrictandKayes.InSudan,thesurveywasimplementedinEnglishandArabic.Informedconsentwasverballyobtainedfromallresearchparticipants.Focusgroupdiscussions.QualitativeFGDswerecarriedouttoaddcontextanddepthtoquantitativefindings.InMali,11FGDswereconductedwithatotalof88participants,includingfiveFGDsinBamakoandsixinKayes.Separatefocusgroupswereheldwithwomenandwithmenofdifferentages(womenoverage40,menoverage40,womenunderage40,menunderage40)andwithpeoplewithdisabilities(bothwomenandmen),representingmigrants,membersofhostcommunities,andreturnedmigrants.InSudan,FGDswereheldwithatotalof118participants,includingcommunityleaders(e.g.campleaders),communitymembers(womenandmenofdifferentages),andyouth(youngwomenandyoungmen)frominternallydisplacedandrefugeecommunities.Wherepossible,separatefocusgroupswereheldwithwomenandwithmen,althoughmixed-genderfocusgroupswerealsoheld,withequalnumbersofwomenandmen.FGDlocationswerethesameasthoseforthequantitativesurvey.72Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossResearchsitesDatacollectionsites(forsurveys,focusgroups,andinterviews)inMaliandSudanweredeterminedincollaborationwithin-countryresearchpartners.Siteswereselectedtorepresentbothmigrantsendingcommunitiesandmigrationdestinationcommunities,accountingforresearchpartners’existingcapacitiesandsecurityandaccessconcerns.73Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA1.NegativeandpositiveenvironmentalchangesobservedbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanObservedchangesMaliSudanTotal(N=91)Bamako(n=47)Kayes(n=44)Total(N=165)DabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)NegativechangesDeforestation64%49%80%63%67%63%58%Reduction,pollutionand/orchangesinwatersources57%60%55%76%98%42%92%Decreaseinrainfall56%36%77%8%012%12%Changesinrainfalltiming34%51%16%48%53%37%58%Soildegradationorerosion32%43%20%41%58%25%42%Longerormorefrequentdroughts30%17%43%16%015%36%Increaseintemperature24%26%23%12%16%7%12%Changesintemperaturetiming21%36%5%10%16%12%2%Decreaseintemperature17%034%9%2%17%8%Lossofaccesstoland15%17%14%52%84%20%56%Morefrequentorsevereflooding11%13%9%52%58%42%56%Morefrequentorseverestorms10%4%16%38%53%28%32%Increaseinrainfall8%11%5%61%82%43%60%Appendix2.SurveydatatablesKeyfindings:perceptionsofenvironmentalchangeinMaliandSudan74Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossObservedchangesMaliSudanTotal(N=91)Bamako(n=47)Kayes(n=44)Total(N=165)DabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)PositivechangesImprovedforestation52%45%59%17%36%10%4%Increasedquantityand/orqualityofwatersources50%51%48%19%29%7%22%Decreaseintemperature17%034%8%13%8%2%Increaseinrainfall14%11%18%54%65%62%32%Lessfrequentorsevereflooding13%11%16%1%002%Shorterorlessfrequentdroughts12%6%18%0000Soilimprovement11%9%14%5%013%0Lessfrequentorseverestorms11%4%18%0000Betteraccesstoland7%014%0000Increaseintemperature6%011%1%02%0Changesintemperaturetiming6%4%7%1%2%00Changesinrainfalltiming6%9%2%1%02%2%75Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA2.TimescaleofenvironmentalchangesobservedbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanTimescaleofchangesMaliSudanTotal(N=91)Bamako(n=47)Kayes(n=44)Total(N=165)DabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Lessthan1year1%02%1%2%0%0%1to3years12%15%9%78%85%92%52%4to6years26%38%14%12%11%5%20%7to10years29%32%25%8%2%5%18%Morethan10years32%15%50%3%0%2%8%TableA3.HumanactivitiesidentifiedascausesofenvironmentalchangesbysurveyparticipantsinMaliandSudanPerceivedcausesMaliSudanTotal(N=80)Bamako(n=42)Kayes(n=38)Total(N=32)DabatBosin(n=22)Elganaa(n=4)Elfao(n=6)Agriculturalpractices69%64%74%11%7%13%12%Energydemands61%48%76%5%4%3%8%Mining53%64%39%1%0%0%2%Industrialactivities49%52%45%0%0%0%0%Herdingpractices43%50%34%5%4%10%2%Fishingpractices19%14%24%0%0%0%0%Actionsofsecurityforcesorarmedgroups19%14%24%0%0%0%0%Changestolandrights/tenure13%026%3%4%3%2%Other8%7%8%1%0%2%2%76Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA4.EffectsofenvironmentalchangesreportedbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanReportedeffectsMaliSudanTotal(N=91)Bamako(n=47)Kayes(n=44)Total(N=165)DabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)NegativeimpactsDecreaseinagriculturalproduction76%74%77%95%85%100%100%Decreaseinherdsize36%40%32%95%87%100%96%Moreseverefoodinsecurity32%38%25%99%98%100%100%Negativehealthimpacts31%32%30%98%100%100%92%Negativeemploymentimpacts29%34%23%71%98%47%70%Decreaseinfishingcatches18%15%20%65%85%100%2%PositiveimpactsLessseverefoodinsecurity13%11%16%1%002%Increaseinagriculturalproduction8%016%0000Increaseinfishingcatches7%014%3%9%00Increaseinherdsize5%2%9%1%2%02%Positiveemploymentimpacts3%07%0000Positivehealthimpacts1%02%0000ImpactsonmobilityIncreaseinmobility27%45%9%93%95%100%84%Decreaseinmobility15%19%11%3%2%08%77Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA5.GroupsidentifiedasmostseverelyaffectedbyenvironmentalchangesamongsurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanMostvulnerablegroupsMaliSudanTotal(N=91)Bamako(n=47)Kayes(n=44)Total(N=165)DabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Women27%36%18%58%71%37%70%Youngpeople31%34%27%9%4%18%4%Olderpeople22%19%25%70%55%72%86%Herders31%34%27%50%84%35%32%Farmers69%89%48%78%80%88%64%Fishers15%15%16%9%22%5%0Othervulnerablegroups4%4%5%4%05%6%78Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA6.CopingandadaptationstrategiesidentifiedbysurveyparticipantsStrategiesMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Changeinworkand/orsubsistenceactivities60%50%70%43%24%33%76%Changesincroptypesand/oragriculturalpractices60%58%62%28%052%30%Migrationoffamilymembers52%70%34%98%100%100%94%Creationofwaterand/orfoodreserves39%30%48%4%2%2%10%Changesinherdingpractices30%32%28%17%038%10%Saleofassets(e.g.livestock)26%26%26%22%13%22%32%Changesinconsumptionhabits25%32%18%17%5%5%44%Changesinfishingactivities15%14%16%12%2%30%0Changesinhousinglocationorstructure13%4%22%37%38%27%48%Keyfindings:copingandadaptationstrategiesinMaliandSudan79Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA7.BarrierstocopingandadaptationreportedbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanBarriersMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Lackoffinancialresources85%80%90%97%96%95%100%Lackoftraining61%56%66%5%4%5%8%Lackofinformation43%34%52%22%24%17%28%TableA8.GroupsfacingthegreatestbarrierstocopingandadaptationidentifiedbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanVulnerablegroupsMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Youngpeople44%38%50%2%006%Women41%48%34%36%44%13%54%Olderpeople27%18%36%84%82%80%90%Othervulnerablegroups20%32%8%36%35%43%30%80Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA9.FormsofassistancefromgovernmentandNGOsreportedbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanFormsofassistanceMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Foodassistance56%50%62%87%100%65%98%Financialassistance(e.g.cashandvouchers,accesstocredit)51%68%34%61%100%8%80%Non-fooditemsforbasicneeds(e.g.shelter,sanitation)38%46%30%46%043%100%Medicalorhealthservices24%28%20%58%22%62%92%Skillsandlivelihoodstraining24%42%6%18%050%0%Agriculturalorfarminginputs(e.g.seeds,tools)22%32%12%12%032%2%Psychosocialservices9%018%4%0014%Earlywarningmechanisms6%8%4%0%000%Supportforre-localisation5%6%4%1%004%Referraltootheragenciesorspecialistservices1%02%1%002%Noassistance19%14%24%————81Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA10.PerceivedchangesinmigrationtrendsamongsurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanMigrationtrendMaliSudanTotal(N=92)Bamako(n=46)Kayes(n=46)Total(N=165)DabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Increaseinin-migration73%78%67%36%0100%0Decreasedinin-migration14%2%26%0000Increaseinout-migration71%87%54%90%100%75%98%Decreaseinout-migration22%2%41%1%002%Keyfindings:migrationdecisionsandtrajectoriesinMaliandSudan82Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA11.TrendsinmigrantsourcesanddestinationsreportedbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanSourceordestinationregionMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Originsofin-migrantsDifferentlocalityinthesameregionofthecountry48%20%76%n/an/a48%n/aDifferentregioninthesamecountry83%74%92%n/an/a3%n/aNeighbouringcountry44%40%48%n/an/a97%n/aAnotherAfricancountry9%8%10%n/an/a0n/aCountryoutsideAfrica5%4%6%n/an/a0n/aDestinationsofout-migrantsDifferentlocalityinthesameregionofthecountry18%22%14%29%078%2%Differentregioninthesamecountry71%94%48%52%060%100%Neighbouringcountry66%92%60%52%100%50%0%AnotherAfricancountry61%48%74%0000CountryoutsideAfrica55%22%88%1%002%83Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA12.Trendsinmigration-destinationtypereportedbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanMigrationtypeanddestinationMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Rural-to-rural2%2%2%27%5%52%22%Rural-to-urban44%88%039%2%35%86%Urban-to-rural2%4%02%008%Towardneighbouringcountries4%2%6%50%100%43%2%TowardAfricancountriesoutsideoftheregion8%2%14%0000Towardinternationalregions(e.g.Europe,Gulfstates)40%2%78%2%03%2%TableA13.TrendsindurationofmigrationreportedbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanMigrationdurationMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Permanent18%6%30%9%4%18%4%Temporary50%62%38%53%25%82%48%Seasonal28%30%26%21%017%50%Don’tknow———24%71%0084Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA14.GroupsidentifiedasmostlikelytomigratebysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanMostlikelytomigrateMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Men65%48%82%53%100%22%40%Women6%10%2%36%100%3%4%Bothmenandwomen6%12%046%100%25%12%Youngmen50%68%32%64%18%100%70%Youngwomen29%56%2%45%100%0%40%Youngpeopleandadults31%38%24%39%0100%8%Elderlypeople1%02%33%100%00TableA15.PrimaryreasonsforgeneralmigrationpatternsaccordingtosurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanMainreasonsformigrationMaliTotal(N=100)Bamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)Economic(searchforbetterworkingandlivingconditions)98%96%100%Foodinsecurity35%54%16%Precipitationchangesaffectingsubsistenceactivities32%52%12%Lackofaccesstonaturalresources31%50%12%Security(e.g.conflict)21%26%16%Temperaturechangesaffectingsubsistenceactivities12%10%14%Environmentalshocks(e.g.flooding)11%16%6%85Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA16.Primaryreasonsforsurveyrespondents’ownmigrationdecisionsinMaliandSudanMainreasonsformigrationMaliSudanTotal(N=72)Bamako(n=34)Kayes(n=38)Total(N=165)DabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Economic(searchforbetterworkingandlivingconditions)100%100%100%57%0%78%94%Rainfallchangesaffectinglivelihoodactivities36%65%11%28%0%33%54%Lackofaccesstonaturalresources32%62%5%16%0%10%42%Foodinsecurity31%41%21%42%0%62%66%Security(e.g.conflict)18%21%16%2%0%0%6%Environmentalshocks(e.g.flooding)13%18%8%85%100%67%90%Temperaturechangesaffectingsubsistenceactivities6%9%3%5%0%0%18%TableA17.PerceivedtimescaleofchangesinmigrationtrendsamongsurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanTimescaleMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Lessthanoneyear1%2%05%010%4%1to3years9%7%11%69%95%68%42%4to6years39%50%28%11%2%2%32%7to10years23%30%15%8%018%6%Morethan10years28%11%46%5%02%16%86Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA18.GroupsidentifiedasleastlikelytomigratebysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanLeastlikelytomigrateMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Olderpeople76%98%54%96%100%90%100%Women71%66%76%13%7%20%12%Youngwomen27%16%38%8%012%12%Youngmen26%10%42%0000Men8%14%2%8%7%13%2%TableA19.BarrierstomigrationidentifiedbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanMainbarriersMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Familyreasons91%90%92%59%33%68%78%Adesiretostayinplace53%62%44%16%16%20%10%Lackoffinancialresources33%18%48%83%93%70%88%Useofin-placecopingstrategies18%10%26%2%05%0Lackofinformation4%08%13%20%17%2%87Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA20.SocioeconomicoutcomesofmigrationreportedbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanOutcomesMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Improved64%56%72%8%9%2%14%Declined16%20%12%88%87%95%80%Neitherimprovednordeclined4%8%02%2%2%2%Improvedanddeclinedindifferentways16%16%16%1%2%02%TableA21.Assistanceprovidedbyfamilyorcommunitymemberstomigrants,identifiedbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanFormsofassistanceMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)None27%32%22%————Regularlysendfoodormaterialobjects23%6%40%5%2%12%0Adviceandguidance22%44%0————Facilitatingmigrationofothers21%4%38%10%25%3%0Regularlysendmoney19%16%22%34%5%47%50%Contributionstocommunitydevelopmentprojects11%6%16%3%08%088Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA22.AssistanceprovidedtofamilyandcommunitymembersbysurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanFormsofassistanceMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Regularlysendmoney54%48%60%33%4%45%50%Regularlysendfoodormaterialobjects37%44%30%4%010%0Contributionstocommunitydevelopmentprojects3%2%4%3%08%0Facilitatingmigrationofothers3%06%2%5%2%0None3%6%0Other———36%36%32%42%TableA23.FrequencyofreturnvisitsandreasonsforreturnamongsurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanPatternsofreturnvisitsMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)AveragefrequencyofreturntolocalityoforiginSeveraltimesayear3%4%2%0000Occasionally42%48%36%56%5%98%62%Rarely45%40%50%2%2%04%Never10%8%12%41%91%2%32%ReasonsforreturnvisitsTovisitfamily77%72%82%42%058%68%Forspecialorreligiousoccasions12%14%10%25%048%26%Professionalorbusinessactivities5%4%6%25%5%62%2%89Changingclimate,changingrealities:migrationintheSahelBritishRedCrossTableA24.Plansforlong-termorpermanentreturntolocalityoforiginamongsurveyrespondentsinMaliandSudanPlansforreturnMaliSudanTotalBamako(n=50)Kayes(n=50)TotalDabatBosin(n=55)Elganaa(n=60)Elfao(n=50)Yes,andplantoreturn77%68%86%6%9%n/a10%Yes,butnotabletoreturn10%8%12%27%76%n/a6%No10%20%029%15%n/a80%Don’tknow3%4%2%1%0n/a4%