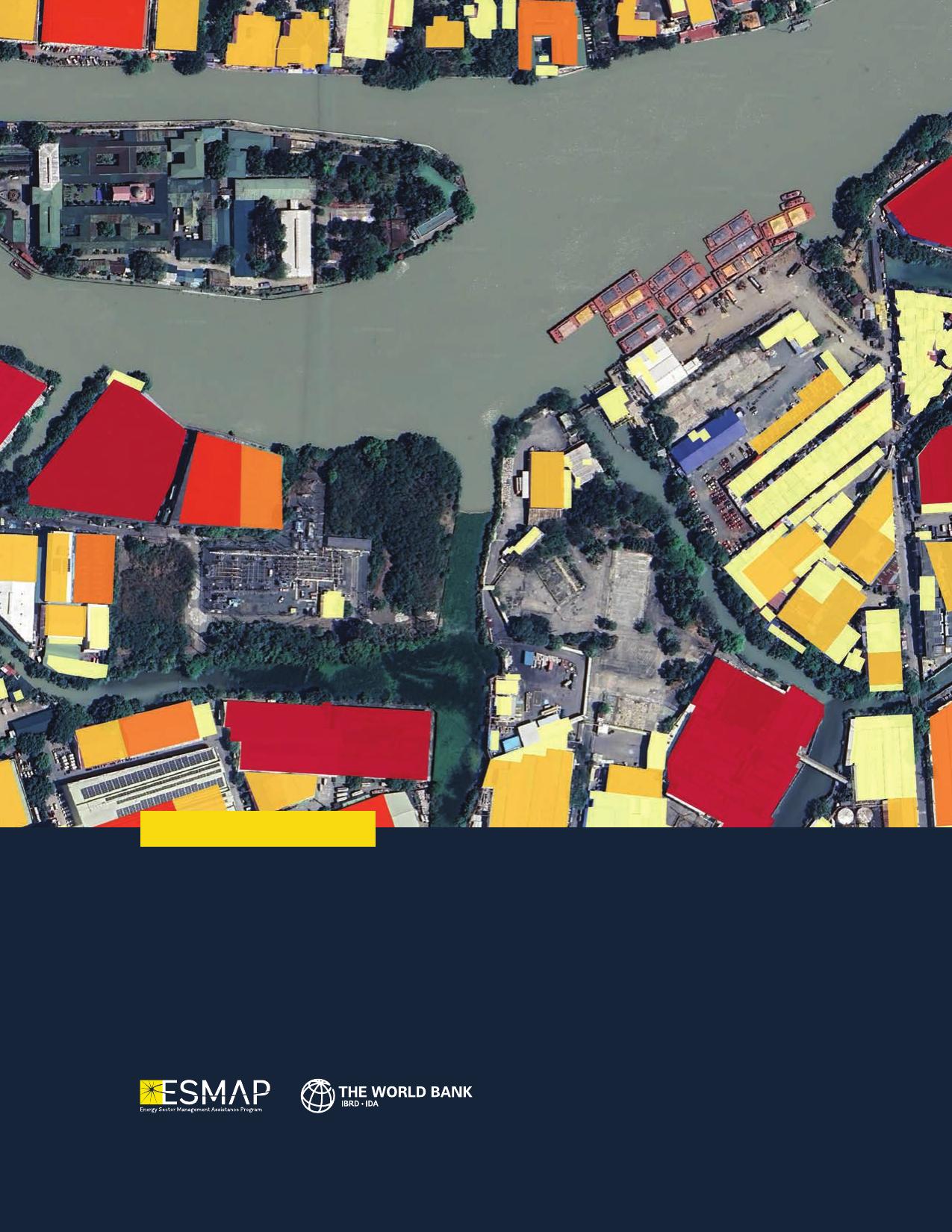

PublicDisclosureAuthorizedPublicDisclosureAuthorizedPublicDisclosureAuthorizedPublicDisclosureAuthorizedTECHNICALREPORTFROMSUNTOROOFTOGRIDPowerSystemsandDistributedPV1©2023InternationalBankforReconstructionandDevelopment/TheWorldBank1818HStreetNWWashingtonDC20433202-473-1000www.worldbank.orgThisworkisaproductofthestaffofTheWorldBankwithexternalcontributions.Thefindings,interpretations,andconclusionsexpressedinthisworkdonotnecessarilyreflecttheviewsofTheWorldBank,itsBoardofExecutiveDirectors,orthegovernmentstheyrepresent.TheWorldBankdoesnotguaranteetheaccuracyofthedataincludedinthiswork.Theboundaries,colors,denominations,andotherinformationshownonanymapinthisworkdonotimplyanyjudgmentonthepartofTheWorldBankconcerningthelegalstatusofanyterritoryortheendorsementoracceptanceofsuchboundaries.RIGHTSANDPERMISSIONSThisworkisavailableundertheCreativeCommonsAttribution3.0IGOlicense(CCBY3.0IGO)http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo.UndertheCreativeCommonsAttributionlicense,youarefreetocopy,distribute,transmit,andadaptthiswork,includingforcommercialpurposes,underthefollowingconditions:Attribution—Pleasecitetheworkasfollows:EnergySectorManagementAssistanceProgram(ESMAP).2023.FromSuntoRooftoGrid:PowerSystemsandDistributedPV.TechnicalReport.Washington,DC:WorldBank.License:CreativeCommonsAttributionCCBY3.0IGOTranslations—Ifyoucreateatranslationofthiswork,pleaseaddthefollowingdisclaimeralongwiththeattribution:ThistranslationwasnotcreatedbyTheWorldBankandshouldnotbeconsideredanofficialWorldBanktranslation.TheWorldBankshallnotbeliableforanycontentorerrorinthistranslation.Adaptations—Ifyoucreateanadaptationofthiswork,pleaseaddthefollowingdisclaimeralongwiththeattribution:ThisisanadaptationofanoriginalworkbyTheWorldBank.ViewsandopinionsexpressedintheadaptationarethesoleresponsibilityoftheauthororauthorsoftheadaptationandarenotendorsedbyTheWorldBank.Third-partycontent—TheWorldBankdoesnotnecessarilyowneachcomponentofthecontentcontainedwithinthework.TheWorldBankthereforedoesnotwarrantthattheuseofanythirdparty-ownedindividualcomponentorpartcontainedintheworkwillnotinfringeontherightsofthosethirdparties.Theriskofclaimsresultingfromsuchinfringementrestssolelywithyou.Ifyouwishtoreuseacomponentofthework,itisyourresponsibilitytodeterminewhetherpermissionisneededforthatreuseandtoobtainpermissionfromthecopyrightowner.Examplesofcomponentscaninclude,butarenotlimitedto,tables,figures,orimages.AllqueriesonrightsandlicensesshouldbeaddressedtoWorldBankPublications,1818HStreetNW,Washington,DC20433,USA;e-mail:pubrights@worldbank.org.PRODUCTIONCREDITSDesignerCircleGraphics,Inc.ImagesSatelliteimageryfromMaxarTechnologiesanalyzedandprocessedbyNEOB.V.(www.neo.nl)toshowbuildingtypeand/orrooftopPVpotential.Frontandbackcovers:Manila,Philippines;page8:Dhaka,Bangladesh;page12:Lagos,Nigeria;page38:Grenada;page46:Izmir,Türkiye;page82:Manila,Philippines.©WorldBank.Usedwithpermission.Furtherpermissionrequiredforreuse.Allimagesremainthesolepropertyoftheirsourceandmaynotbeusedforanypurposewithoutwrittenpermissionfromthesource.TABLEOFCONTENTS5ABSTRACT47�CHAPTER4:APPROACHESTOPOWERSYSTEMPLANNING6ABOUTTHISSERIESWITHDPV7ACKNOWLEDGMENTS47�TraditionalPowerSystemPlanningApproachesVarybyCountryandAre9KEYMESSAGESEvolving13�CHAPTER1:HOWIMPORTANT49�PowerSystemPlanningcanAddressISDPVFORPOWERSYSTEMDPVinaVarietyofWaysPLANNERSANDOPERATORS?51�GeneralStepsandPrinciplesforPower13�DPVhasDistinctImplicationsforPowerSystemPlanningwithDPVSystemsAroundtheWorld60Conclusion:BeyondTechnicalIssues16�DifferentDPVSystemsFeedAll,SomeorNoneofTheirOutputtotheGrid61�ANNEXA:TECHNICALDESCRIPTIONSOFNINEDPVUSECASESFORLMICs18�DPVImpactsonPowerSystemsEvolveasDeploymentGrows61UseCase1:BillReduction61UseCase2:Least-CostBackup23�CHAPTER2:TECHNICAL64UseCase3:Least-CostGenerationSOLUTIONSFORGRID-FRIENDLY65�UseCase4:Transmission&DistributionDPVAlternative24SolutionsMenu1:LocalLoadBalancing66UseCase5:UtilityBootstrap66UseCase6:AncillaryServices30�SolutionsMenu2:EnhancingHosting67UseCase7:CommunitySocialSupportCapacity69UseCase8:FinancialLossReduction70UseCase9:BoxSolution39�CHAPTER3:GRIDCODESFORGRID-FRIENDLYDPV71�ANNEXB:DISTRIBUTIONGRIDTECHNICALSTANDARDS39SuggestedGridCodeElementsforDPV73ABBREVIATIONS41�TheRationaleforSpecifyingDPVInverterBehaviorinGridCodes74GLOSSARY43�DPVSystemEquipmentStandards77REFERENCESandCertificationareImportantforEnforcementofGridCodes44�ProceduresforDPVConnectionShouldbeSimpleandPragmatic3ListofFiguresFigure12:PotentialImpactsofVariableFigure1:OverviewofPotentialPowerSectorRenewablesonGridsatDifferentTimeIssuesandSolutionsforGrid-FriendlyDPV10ScalesandSpatialAreasforStudies53Figure2:TypesofArrangementsforFigure13:ASiteAnalysisUsingtheDistributedGenerationFedintotheGrid17GlobalSolarAtlas55Figure3:VoltageAlongaRadialFeederListofTablesUnderDifferentConditionsofLoadandDPVOutputFedtoGrid19TableA:PowerSystemSolutionstoFigure4:RapidEveningDropinDPVDPVIssuesfromLowtoHighPenetration25GenerationwithRampUpofOtherTableB:RelevantGridCodeItemsforSources,AustralianExample21DPVSystemRequirements40Figure5:DistributionGridEffectsfromDPVbyLevelofPenetrationandCostListofBoxesRangeofSolutions26Box1:DPVUseCaseswithTechnicalFigure6:PVSizedGreaterthantheInverterBenefitsforPowerSystems15CapacityClipsPeakbutIncreasesBox2:RadialversusOtherTypesofNon-PeakOutput29DistributionFeeder20Figure7:TechnicalServicesthatDPVBox3:AggregationofDPVIntoVirtualInvertersMayProvideBasedonPowerPlants27AvailableCharacteristics31Box4:Grid-FollowingandGrid-FormingFigure8:UserInterface,ESMAP’sSimplifiedInverters33SolarPVForecastingTool36Box5:TechnicalScreeningCriteria:Figure9:GridCodeFormulationGuidancebyHelpfulorNot?45GridSizeandLevelofVariableRenewableBox6:AssessingIntegrationofRenewablesPenetration42forThailand’sPowerSystem50Figure10:Certificationandthe‘ChainofBox7:MappingDPV’sTechnicalPotential54Trust’forDPVEquipment44Figure11:GeneralStepsRelevantforDifferentBox8:DistributionSystemPlanningTools57ApproachestoPlanning514FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVABSTRACTRapidgrowthofdistributedphotovoltaics(DPV)hasupendedhowengineerstraditionallythinkaboutelectricpowersystems.Consumersnowincreasinglygeneratetheirownpowerandfeedittothegrid.PoorlymanagedDPVposesdistinctrisksforpowersystemsaspenetrationincreases.Yet,low-andmiddle-incomecountriescanbenefitfromthiscleandistributedenergyresource.HowcanDPVsystems,distributionnetworks,andthepowersystembeplannedandoperatedtomitigaterisksandreaptechnicalbenefits?Thisreport,thesecondinaseriesofthree,presentsamenuoftechnicalsolutionsapplicableacrossdiversecontexts.BalancingDPVsupplywithlocalloads,asfaraspractical,canhelpkeepgridoperationswithintechnicallimits.Agrid’shostingcapacityforDPVcanalsobeenhancedonmultiplefrontstocopewithchangedconditions.Manysolutionsareinexpensive.Inverterprogrammingunlocksvaluableservices.Anticipatingchallengesandopportunitiescanavoidcostlyfixes.Allcountriescanbenefitfromagridcodeandplanningapproachthatreflectexpectedgrowthofdistributedresources.Prudenttechnicalcriteriacanbeusedtostreamlinenewapprovalsforgrid-friendlyDPV.Technicalmeasuresalsorequirethetimelycapacitybuildingofpersonnel.Examplesofstandardsareprovidedforreadersseekingmoredetails.5ABOUTTHISSERIES:FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRIDThisreportisthesecondinaseriescalled“FromSuntoRooftoGrid”producedbytheWorldBank’sEnergySectorManagementAssistanceProgram(ESMAP).Distributedphotovoltaics(DPV)istheworld’sfastest-growingtechnologyforlocalgenerationofelectricpower.Thisseriesshowshowlow-andmiddle-incomecountriescantakefulladvantageofDPVasalow-cost,easy-to-installmodulartechnologyindiversecontextsfromlargestablepowersystemstosmallislandsandregionsmarkedbyfragility.Interrelatedtopicsacrossthreereportstargetarangeofreaders—fromnon-expertdecisionmakerstoplannersandregulators—toofferamenuofideas,approaches,andexamplestohelpdemystifychallengesencounteredindeployingDPV.TheseriesaimstohelpreadersrealizediversepotentialbenefitsofDPV,whetheronitsownorpairedwithotherdistributedenergyresourcessuchasbatteries,demand-sideenergyefficiency,anddemand-responsemechanisms.Therelationshipbetweenthethreereportsandintendedaudiencesisdepictedbelow.RELATIONSHIPOFREPORTSANDINTENDEDAUDIENCESOFTHESERIESDecisionmakers,non-experts1DPVinEnergy2PowerSystemsPlanners,SectorStrategiesandDPVregulators,policy•WhatisDPVandwhatare•Whataretechnicalstrategiestomakers,thebenefits?managehighsharesofDPV?experts•Whatplanningtoolsare•WhatarecurrentDPVneededforDPV?markettrends?DPV•WhataretheuseUsecasesforDPV?Cases3DPVEconomicsandPolicy•WhatsystemchallengescanDPVaddress?•Whoarekeystakeholders?•Howcanappropriateusecasesbeidentifiedandassessed?•HowcanDPVprogramsbedesignedandimplemented?Asarelativelynewtechnologywithdiverseapplications,knowledgeofhowDPVcanimpactandinteractwiththegridsvariesgreatly.Forthisseries,DPVisdefinedsimplyasanyphotovoltaicslocatedwithornearconsumersconnectedtoanelectricitygrid.Thisdefinitionimpliesnominimumormaximumsize.SystemscanrangefromasinglePVpanelof250watts,forexample,uptotensofmegawatts(MW)capacity.DPVcanbefoundonrooftops,ascanopiesabovecarparksorirrigationcanals,andinfloatingarraysonindustrialponds.Inadvancedcontexts,solarcellsarenowevenbeingintegratedintoconstructionmaterialssuchaswindowglass,rooftiles,andthesurfacesofsidewalksandhighways.DifferentDPVsystemsfeedall,some,ornoneoftheirelectricoutputtothegrid.Somegrid-tiedDPVsystemsprovidebackupelectricitytoconsumersincountries6withfrequentoutagesofgridpower.Off-gridinstallations,thatis,forconsumersorfacilitieswithnogridconnection,arenotthefocusofthisseriesexcepttotheextentthataccesstogridelectricitymaybecomeavailablewithintheireconomiclifetimes.Thefirstreportinthisseries,“DistributedPVinEnergySectorStrategies”(ESMAP2021),surveysDPVindifferentcountrycontexts.Aimedatenergyministriesandotherdecisionmakers,thisreportintroduceskeyconcepts,theDPVmarket,andnineusecases,orapplications,ofDPVtohelpsolvedifferentspecificproblemsfacedbyvariouslow-andmiddle-incomecountries.Considerationsfromapowersystemperspectivearethetopicofthissecondreport,“PowerSystemsandDistributedPV.”Thisreportisaimedmainlyatatechnicalaudience—planners,distributionandtransmissiongridoperators,andexpertstaffofenergyauthorities.However,thereportalsoaimstointroducetheissuessimplyenoughfornon-technicalreaderstobecomefamiliarwiththem.Thethirdreport,“DistributedPVEconomicsandPolicy,”detailsthestrategicobjectives,cost-benefitanalyses,regulatoryissues,andbusinessmodelsforDPV.Takentogether,thesethreereports(andtheirkeymessagesfordifferentstakeholders)aimtoenablelow-andmiddle-incomecountriestoharnesspowerfromthesuntobenefitallconsumersconnectedtothegrid.Formoreinformation,visitwww.worldbank.org/energyandwww.esmap.org/esmap-from-sun-to-roof-to-grid-distributed-pv.ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThisreportisanactivityoftheWorldBank’sEnergySectorManagementAssistanceProgram(ESMAP).ThereportleaderandmainauthorisAlanDavidLee.ThereportserieshasbeenledbyAlanDavidLee,ZuzanaDobrotkova,andThomasFlochel,withsupervisionsupportfromChristophedeGouvello.Forthisreport,manyindividualsandpartnerorganizationscontributedcontentand/orreviewsuggestions.Theseinclude:WorldBankstaffandconsultants—AbhinavGoyal,AshokSarkar,ClaireNicolas,ChrisGreacen,ChongSukSong,DaronBedrosyan,DebabrataChattopadhyay,JeremyLevin,KojiNishida,LeopoldSedogo,LuisMaurer,MohuaMukherjee,MonaliRanade,OliverKnight,PierreAudinet,SandraChavez,SilviaMartinezRomero,SimonMüller,TarekKeskes,TatyanaKramskaya,TorreyBeek,andWojciechKrawczyk;EnergynauticsGmbH—ThomasAckermannandEckehardTröster;HeymiBahar(IEA);TobyCouture(E3Analytics);USNationalRenewableEnergyLaboratory—OwenZinaman,NateBlair,FranciscoFlores-Espino,JulietaGiraldez,AdarshNagarajan;andNEOB.V.—FangFang.ManagementguidancewasprovidedbyDemetriosPapathanasiou,GabrielaElizondoAzuela,andRohitKhanna.StevenKennedyandFayreMakeigprovidedcopy-editing.Allviewsexpressedandanyshortcomingsarethoseoftheauthors.ACKNOWLEDGMENTS7RooftopsanalyzednearsubstationinDhaka,BangladeshKEYMESSAGESRapidgrowthofdistributedphotovoltaics(DPV)hasupendedhowpowersystemplannersandoperatorsthinkaboutelectricitygrids.Fallingcostsofsolarelectricityhavemadeon-sitegenerationandconsumptionalow-costoptionforaccesstonew,cleanpowerglobally.PVsystemslocatedclosetoconsumersenablethemtoself-supply,and—ifpermitted—feedintothegrid.DPVthuschallengeshowutilitiestraditionallygenerate,transmit,anddistributepowerasaone-wayflowfromcentralplantsdowndiscretesystemlevelstoconsumers.ManycountriesarelearningtosuccessfullymanageDPVatincreasingsharesoftotalpowergeneration.Low-andmiddle-incomecountries(LMICs)standtobenefitfromemerginglessons.Thisreportexplainscommontechnicalchallengesandopportunitiestoconsider,andstepstotakegiventhecurrentandpotentialfuturelevelsofDPV.Fortechnicalreaderswantingmoredetails,thereportpointstoexamplesofstandardsandtechnicalprocedurespublishedbyotherinstitutions.Well-managedDPVofferspotentialtechnicalbenefitstopowergridsinseveraldistinctways.DPVsystemscan,withotherdistributedenergyresources(DER),helpinLMICstovariously:(a)supplyleast-costgenerationtothegrid,especiallywherelandisconstrained;(b)defercertaintransmissionanddistributionupgrades;(c)provideancillarygridservices;and(d)“bootstrap”orupgradeunderperformingutilitiesbyimprovingserviceandincreasingbillcollectionsforconsumersinamicrogrid.1Theseandotherpotentialusecases,plusrapidinstallationtimes,enhanceDPV’svalueasacontributiontoleast-costdecarbonizationorlow-emissionsdevelopmentplans.BenefitsfromDPV,however,dependonappropriatepowersystemplanning,investmentsandoperations,suitedtothelocalcontext.AsDPVgrowsfromlowtohigherlevelsofpenetration,differenttechnicalriskstypicallyemerge.ThesearesummarizedinFigure1(leftcolumn).EffectsofDPVonpowersystemsaregradualandthespecificissuesthatariseasDPVgrowscanvaryfromplacetoplace.Atalowlevelofdeployment,DPVmayhavenegligibleimpacts,especiallyinlargergridsystems.DPVpowerfedtothegridcanusuallybesteppeduptohighervoltagelevelsoftenwithoutsignificanttechnicalmodificationstothedistributionsystem.However,poorlymanagedDPVcancausesystemoperatinglimitstobebreachedatcertaintimes.SinceDPVcanbeinstalledinamatterofweeks,atamuchfasterratethanbulkpowerplants,preparingforrisinglevelsofpenetrationisimperative.TheamountofDPVthatagridcanintegratesafely,whilekeepingwithinspecificoperationallimits,isnotfixed.HostingcapacityforDPVisadynamic,multi-facetedthreshold.Itcanvarywithinagridandovertime,dependingonthedesignandoperationofthepowersystemandofDPVsystems—inaggregateandlargeindividualsystems.AmenuofpotentialtechnicalsolutionsexisttohelpensureDPVisgrid-friendly.SeeFigure1,middleandrightcolumns,whichcorrespondtotwobroadapproachesasfollows.1.Localload-balancing.MatchingDPVsupplyandlocaldemandwitheachotherasmuchaspracticalcanhelpkeepgridswithinspecifiedsystemoperatinglimits.Thistypeofinterventionaimstokeepnetload2relativelystableandcertain,akintoloadconditionswithoutDPVoreven,ideally,toimproveuponthem.1“Bootstrap”heremeansusinginitialminimalresourcestoliftoneselfupoutofabadsituation.2“Netload”herereferstodemandforbulkgridelectricityexcludingdemandforelectricityservedbydistributedand/orbulkvariablerenewablesources.SeeGlossaryforthisandotherkeytechnicalterms.9FIGURE1:OVERVIEWOFPOTENTIALPOWERSECTORISSUESANDSOLUTIONSFORGRID-FRIENDLYDPVPowerSystemRisksfromSolutionsMenu1:SolutionsMenu2:DPVatRisingLevelsLocalLoadBalancingEnhancingHostingCapacityLowDPVpenetrationSupply-demandcoordinationDPVinverterprogramming•Breachofvoltagelimits•Promoteefficientdemandaheadof•Voltagemanagement•CopewithgriddisturbancesMediumDPVpenetrationdesigningDPV•Supportpowerquality•Disruptiontofault•Grid-formingmode•AnalyzehostingcapacityandgridprotectionschemecongestiontoinformstrategicsitesGridequipmentadjustmentorandDPVdesignupgrade•Breachoftransformercapacitiesandconductor•FavorlargeDPVclosetosubstations•Voltagecompensationthermalratings•Usedigitaltechnologiestomonitorequipment•IncreasedvariabilityandandcontrolDERs•On-loadtapchanginguncertaintyofnetloadtransformers•AggregateDERsintovirtualpower•Poorresponsetogridplants•Protectionschemesettingsdisturbances•HarmonicfiltersSupply-sideadjustmentsEnhancepowersystemflexibilityHighDPVpenetration•CalibratePVsizesandanglesto•Improveforecasts•Powerqualityproblems•Automateoperations•Lackofsynchronousservelocalpeakloadsanddiversify•Expandbalancingareasproductiontime•Shortendispatchintervalsandgeneration•DesignDPVsystemswithoptimallyscheduleupdateshighDC:ACratio(inverterclipping)•Fast-actingreserve•SizeDPVtomatchefficient•Synchronouscondensersprojectedlocalenergydemand•Limitfeed-indynamicallyorstaticallyDemand-sideadjustments•Demandresponse•EnergystorageSource:Originalbytheauthorsforthisreport.Note:Solutionslistedinthemiddleandright-handcolumnmayaddressmultiplerisksintheleft-handcolumn.Case-by-caseappraisalisimportanttodesignandcostanyintervention.HighDPVpenetrationismostlyrelevantforsmallpowersystems.HostingcapacityenhancementsmarkedwithanasteriskareforhighDPVpenetrationissues,whicharerarelyaconstraintforDPVuptakeinlargerpowersystems.ThresholdsforlowandmediumpenetrationarediscussedinChapter1.2.Hostingcapacityenhancements.Load-balancingmaynoteliminatetheneedforapowersystemtocopewithnewpressuresresultingfromDPVdeployment.Agrid’shostingcapacitycanbeenhancedbyDPVinverterprogramming,gridequipmentadjustmentsandupgrades,andflexibilityresourcesinthepowersystemoverall.Inassessinginterventionsforgrid-friendlyDPV,somegeneralprinciplesapply.Considerawidevarietyofoptionstoaddresstypicaltechnicalissues;considerifregulationsneedupdatingtoallownewoptions;considerthevalueofambitiousinvestmentoptionstoaccommodatelong-termdevelopments;andprioritizethemostcost-efficientsolutions.Costscanvaryfromonepowersystemtoanother,socase-by-caseappraisalisimportant.PlanningadequatelyaheadcanavertthemostcostlysolutionsorblanketrestrictionsonDPV.Historically,DPVhasencounteredproblemsonlywhenitsdeploymentpotentialhasbeenunderestimated,10FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVorwhendeploymenthasnotbeenaccompaniedbyastrategytomanageitsintegration.Highcostsresultfromneedingtoreplaceorupgradegridassetsbeforetheendoftheireconomiclifetime.MostoperationalmeasureshaveverylowcostswhilemostDPVplanningandinvestmentsolutionshavelowtomoderateincrementalcosts.SomelocalconditionsmayenableasignificantshareofDPVtobeintegratedwithpurelyoperationalmeasuressuchasinverterprogramming.Invertersneedstohaveappropriatecapabilitieswiththerightsettingsatinstallation;retrofittinginvertersismoreexpensive.Allcountriesshouldadoptagridcodethatreflectsexpectedfuturegrowthofdistributedenergyresources.DPVcanbecomerelevantfortheoverallpowersystem,sotechnicalrulesmustkeeppacewithinstalledDPVcapacity.Countrieswithnogridcodeshoulddeveloponeassoonaspossible.EveningridswithlowDPVpenetration,specifyingadvancedinverterfunctionstodaycanreducetheneedtochangesystemsinthefuture.Itisimportantforgridcodestobeeasytoimplement.TechnicalapprovalsforDPVinstallationstoconnecttothegridcanbestreamlinedwithprudentscreeningcriteriaforsystemsthatmeetcertainspecifications.IntegratedpowersystemplanningoradedicatedintegrationstudyarerecommendedwhereDPVmaybedeployedathighrates.TraditionalcapacityexpansionandproductioncostmodelscanbeadjustedtoaccountforDPVsimplyasa“negativeload.”However,thismaynotcaptureenoughdetailtoreflectimportantchallengesandopportunitiesthatemergeasrenewablesanddistributedresourcesbecomemoreprevalent.Distributedenergyresourcesspurnewprocessestoanalyzeanddesignpowersystemsaccountingforalternativefuturescenarios.Foranyapproachtopowersystemplanning,engagingDPVstakeholdersearlycanhelpfosterconvergenceonkeyissues.GoodprinciplesincludetosetplanningobjectivesthataccountforcurrentandpotentialnewusecasesofDPVandawiderangeofpotentialoperatingconditions.Considerthetechnicalpotentialofdistributedresources,deploymentforecasts,distributionnetworkperformanceindices,andoptionstoenhancehostingcapacity.Eveninlow-incomecountriesorthosemarkedbyfragility,low-costgeoreferenceddatasetsanddataanalysistoolsmaybehelpful.Scenariosbuildingonthesecanestimatecurrentandenhancedhostingcapacitieswithanalysistoevaluatealternativesandoptimizefortheobjectives.PlanningoutputscaninformDPVdeploymenttargets,prioritizeinvestmentstoenhancethenetwork,andguidefurthersite-specificanalysesforkeylocalprojects.LMICgovernmentswoulddowelltoseekadequateandongoingtechnicalandfinancialsupportforcapacitybuildinginDPVoperationsattheutilitylevel,attheearliestopportunity.Technicalmeasuresalonearenotenough.DPVintegrationalsoneedseffectivebusinessmodels,regulation,financing,andtimelycapacitybuildingofpersonnel.11RooftopsanalyzedinLagos,Nigeria1:HOWIMPORTANTISDPVFORPOWERSYSTEMPLANNERSANDOPERATORS?Thisreportexploresthetechnicalaspectsofgrid-tieddistributedphotovoltaics(DPV)toinformpowersystemoperatorsandplannersespeciallyinlow-andmiddle-incomecountries(LMICs).DPVisarelativelynewtechnologyandhasdiverseapplicationsacrosscontexts.Assuch,DPVanditstechnicalimpactsareoftenmisperceived.ThisreportseekstoexplainkeyissuessopowersystemplannersandoperatorscanidentifysolutionstomaximizeDPVbenefitswhileavoidingadverseoutcomesforthegrid.ThischapterestablishestheimportanceofDPV,first,byhighlightingitsglobalgrowthandtherolesthetechnologyplaysinenergysectorpriorities,especiallyinLMICs;second,byoutliningDPV’sincrementalimpactsonthepowersystemovertime.Chapter2subsequentlypresentsamenuofoptionsforgrid-friendlydesignandmanagementofDPVsystems,distributiongrids,andthepowersystematlarge.Chapter3describestheimportanceofgridcodeconnectionstandardstoscaleupgrid-friendlyDPV.Chapter4concludeswithapproachestopowersystemplanningwithDPV.DPVHASDISTINCTIMPLICATIONSFORPOWERSYSTEMSAROUNDTHEWORLDDPVisirrevocablychangingpowersystemsaroundtheworldDPVisirrevocablychangingpowersystemsaroundtheworld,includingindiverseLMICs.Thinandmodular,solarphotovoltaic(PV)cellscanbeeasilyinstalledinmyriadwaysonornearsitesofelectricityconsumption.ThesepropertiesdistinguishDPVfrombulkgenerationsources—includinglarge-scaleground-mountedPVpowerplants—andfromotherdistributedgenerationtechnologies.Bulk(centralized)powergenerationtechnologiesoccupylargeparcelsoflandandusuallytransmitenergytoconsumersoverlongdistances.Economiesofscalemeanthatpowerstationsforbulkgenerationofelectricitymaybeenormousphysicalstructuresrequiringlargededicatedparcelsofland,oftenlocatedatadistancefromcentersofpowerdemand(i.e.,urbanareasandindustrialzones).Transmissionsystemsaredesignedtoconveypowerefficientlyoverrelativelylongdistancesandenhancereliabilityofsupplyfrombulkpowersourcestolocalgrids.However,manycountriesfacelandconstraints,compoundedbyclimaterisksandenvironmentalconsiderationsaroundcompetinglanduses.Incontrast,DPVgeneratespowerfromdiverselocations,servingeitheritsdirectoperators,orfeedingelectricityintothepowergrid,withoutnecessarilydetractingfrompreexistinglanduses.DPVisalsodistinctfromotherdistributedgenerationtechnologies,suchasfuel-basedgeneratorsetsorsmall-scalewind,asDPVdoesnotrelyonmovingpartsorfeedstock.ThecosttooperateandmaintainDPVisthusextremelylow.13Integratedproperly,DPVcanactuallysupportthelocalenergyutilityandthenationalgrid.However,theresultingnewnetworkarchitecturehasconsequencesthatmustbeconsideredbypowersectorauthorities.GlobalGrowthofDPVisSettoContinueGlobalinstalledcapacityofDPVexplodedoverthepasttwodecadesfromjustafewmegawatts(MW)in2000toacumulativetotalofover383gigawatts(GW)bytheendof2021.Thisincludes238GWcommercialandindustrialPVandover145GWofresidentialPV(IEA2022a).MuchofthisgrowthisoccurringinChinaandIndia,althoughDPVisalsoexpandingacrosssmallisland-nationsandlow-incomecountries.DPVhasgrownsteadilyatagloballevel,rivalingutility-scalesolarandovertakingcoalandnuclear—combined—innetcapacityaddedeachyear.EvenastheCOVID-19pandemicslowedgrowth,newDPVinstallationsofferedadirectresponsetothegloballockdownsbyhelpingtopowerhealthclinicsinregionswithunreliablegridservice.DPVisalsoboostingeconomicresilienceandrecoverystrategies,includingjobcreation.Recentrisesinnaturalgaspricesofseveralregionshavepromptednear-termforecastsofDPVdeploymenttorevisedupward.Overthelongerterm,evenunderaconservativescenariobasedoncountries’recentlystatedpolicies,globalinstalledcapacityofPV(atallscales)isprojectedtoreachanorderofmagnitudegreaterthananyothersingletechnologybythe2040s(IEA2022b).Ascenarioofmoreambitiousdecarbonizationwillonlymagnifythisscale-up.Assuch,theriseofPVpluswindpoweraresettofundamentallyreshapepowersystemsandsignificantlyincreasethedemandforpowersystemflexibility.DPVhasDiverseUseCasesinLow-andMiddle-IncomeCountriesForLMICs,DPVcancontributeindistinctwaystothegoalofreliable,affordablecleanenergyforall.ManyLMICsareseeingsteepbutuncertaingrowthindemand,unreliablegrids,andrapidlychangingcircumstances,especiallyinareasfacingfragility,conflict,andviolence.Morethan50millionforciblydisplacedpeopleliveinurbansettingswheregridcapacityisstrained.Globally,anestimated350to500GWofdieselgeneratorssupplytemporaryorbackuppowertoconsumersofgridelectricity(IFC2019).Thesearenoisygeneratorsthatalsocreatepollution.Inaddition,dieselisacostlyfuelvulnerabletosupplydisruptions.Liketheselargeurbansettlements,manysmallislandsrelyonexpensiveoilimportsforpower,whiletheylackthelandrequiredtobuildground-basedpowerstationsortransmission.Formostcommunities,resiliencetorisksfromclimatechangeandcrisesisahighpriority.ThelocalnatureofDPV,thefactthatitcanachievehighaggregatecapacityfrommanyindividualplants,alsoaddstoresilience.Evenifaportionofsystemsfail,theoveralloutputwillnotbeaffectedasmuchaswithfewer,largeplants.Ineachoftheabovescenarios,DPVcouldprovidesignificantbenefitswhendeployedonitsownorcombinedwithotherresources.Systemscanbescaledtomatchavailableneedsandbudgetsandoperatedwithnofuelcosts,noemissions,andminimalmaintenance.DPVpairedwithbatterystorageisincreasinglycommonandgenerallyconfiguredtoprovidebackuppowerintheeventofapowerfailureontheutilitylines(ESMAP2020b).ThereareseveraltechnicaloptionsforconnectingbatterieswithaDPVsystem,andsystemscanalsobeconfigured,withtheproperinverter,tochargethebatteryfromthesolararrayaswellasfromthegrid.Whenusedinconnectionwithbatteries,DPVcanpowerconsumersindependentlywhenthegrid,orsunshine,areunavailable.Grid-tiedDPVschemescanalsoinformthedesignofoff-gridsystemsthatmightlaterbeconnectedtoanexpandedmaingrid.DPVCanProvideTechnicalBenefitstoPowerGridsWell-managedDPVofferspotentialtechnicalbenefitstopowergridsinseveraldistinctways.Thefirstreportinthepresentseries(ESMAP2021)introducednineusecases,orapplications,ofDPV,whicheachrespondtoaspecificproblemfoundinLMICs.Fromapowersystemperspective,fouroftheseusescasesstandout14FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVBOX1DPVUseCaseswithTechnicalBenefitsforPowerSystemsThefollowingtwousecasesarealreadyemerginginnumerouscountries.•DPVmaybepartoftheleast-costgenerationmix.Evenbeforeconsideringthevalueofavoidedpollutionandcarbonemissions,DPV’sproximitytoloadscanavoidtransmissionlossesandhelpovercomegridinfrastructureconstraintsorlackoflandavailableforbulkpowergeneration.ThisistrueregardlessofwhetherDPVsystemsfeedall,some,ornoneoftheiroutputtothegrid.HighpenetrationofDPVcandisplacetheneedforgenerationfrombulkpowerplants,suchasinsmallislands.Thisisespeciallyrelevantinpowersystemsthatfaceperiodsoflightdemand.•DPVcanhelputilitiesdefercertaintransmissionanddistributionupgrades.ThisispossiblewhenpeakdemandoccursduringthedaytimeandDPVhelpsmeetlocaldemand,plannedwithotherDERsuchasdemand-response,energyefficiency,andbatterystorage.Twomoreusecasesrepresentopportunitiesyettobewidelydeployed.•AncillarygridservicescanbeprovidedbyinvertersinDPVsystems,inisolationandinaggregate.Forexample,inverterscancontrolreactivepowerforvoltagemanagementorcurtailactivepowerforcongestionmanagement.MoreandmoregridcodesarebeingupdatedtorequiresuchcapabilitiesofinvertersbeforeapprovingnewDPVconnectionstothegrid.Policyincentivestoexploitmoreadvancedancillaryservicesareanewfrontier.•Finally,utilitiesinaviciouscycleofchronicunderperformancecanusegrid-connectedmicrogridswithDPVasa“bootstrap”toimproveservicereliability,expandaccess,andincreasebillcollections.SeeAnnexAfortechnicaldescriptionoftheseandotherDPVusecasesforLMICs.fortheirtechnicalimplications:least-costgeneration;transmissionanddistribution(T&D)alternative;ancillarygridservices;andbootstrap3,asdescribedinBox1.AnnexAprovidesatechnicaldescriptionofallnineusecasesincluding,forthemosttechnicalaudience,electricalengineeringdiagramstoillustratehoweachusecasemaybeconfigured.Acrosstheusecases,DPV’srapidinstallationtimesenhanceitsvalueasacontributiontoleast-costdecarbonizationorlow-emissionsdevelopmentplans.Acrosscountries,allsuchplanscallforanincreaseinelectrificationofendusesandinsolaramongotherpowersources.3“Bootstrap”heremeansusinginitialminimalresourcestoliftoneselfupoutofabadsituation.1:HOWIMPORTANTISDPVFORPOWERSYSTEMPLANNERSANDOPERATORS?15Latersectionsofthisreportwillrefertotheaboveusecases,linkinggeneralconceptswithreal-lifeapplications.Inpractice,twoormoreusecasesmaybecombinedtogeneratesynergiesinasingleprojectorschemeorcombinedwithotherDERandschemessuchasenergyefficiencyandmicrogrids.AllbenefitsfromDPV,however,dependonappropriateplanning,investments,andoperations,suitedtothelocalcontext,whichinturndependsontheinstitutionalcapacityofenergyagencies.EnhancingtheInstitutionalCapacityofUtilitiesInvestmentinutilityengineers’trainingintechnicalaspectsofDPVisanimportantprerequisiteforlaunchingadecentralizedgenerationprogramaspartofacountry’scleanenergytransition.Withoutsufficientnumbersofadequatelytrainedstaffinthedistributionutility,itislikelythatDPVcustomersawaitingapprovalfortheirsystemstobecommissioned,willhavetowaitformanymonths.Insomecases,theymayalsobepayinginterestonaloanfortheirinstalledbutnot-yet-commissionedDPVinvestmentwhilereceivingnobenefits,notevenfromself-consumption.TheresultantlossofreputationandconsumerappetiteforDPVwillbehardtorecoverfrom.IfconsumerinterestfadesitwilllikewisebedifficulttocreateacompetitiveecosystemoftherequiredserviceprovidersthatunderpintheDPVsector’sgrowth.LMICgovernmentswoulddowelltoseekadequateandongoingtechnicalandfinancialsupportforcapacitybuildinginDPVoperationsattheutilitylevel,attheearliestopportunity.DIFFERENTDPVSYSTEMSFEEDALL,SOMEORNONEOFTHEIROUTPUTTOTHEGRIDToFeedorNottoFeedtheGrid?BeforediscussingDPVindetail,itisimportanttorecognizeafundamentalconfigurationchoice:whetherall,some,ornoneoftheDPVelectricoutputisfedtothedistributiongrid,versususedforon-siteself-supply.Thisreportseriesusesatypologyoffeed-inarrangements,describedbelowandillustratedinFigure2.WhiledescribedintermsofDPV,thetypologyappliestoallsourcesofdistributedgeneration.•Feed-all.AllDPVoutputisfedintothegrid.ThisarrangementcanfurthercategorizedbywhetherDPVisconnectedtoaconsumer’spowercircuits(consumerside)ortoadistributiongriddirectly(gridside).Afeed-allDPVarrangementwithanon-siteconsumerisknowninsomeliteratureas“buyall,sellall”becausetheconsumerbuysalltheirpowerfromthegrid.Feed-allarrangementsmayalternativelybeonasitewithnotolittlegridconsumption,suchasground-mountedDPVinanemptylot.Sucharrangementsresemblestandardpowerplantsbutserveadistributiongriddirectlyatlowervoltagelevelsthanbulkgeneration.•Feed-some.SomeoftheDPVoutputisconsumedon-site(orstoredforlateruse)inlieuofconsumingpowerfromthegrid.TheremainderoftheDPVoutputisfedintothegrid.Feed-somemodelsmayinvolveasingle(bidirectional)“netmeter”thatmeasuresthenetflowofpowertoorfromthegrid,ortwo(unidirectional)“grossmeters,”oneforeachdirectionofpowerflow.•Feed-none.AllDPVoutputself-suppliestheconsumer.Feed-noneinstallationscanstillaffectthegridbyalteringthecustomer’sconsumptionprofile.Forexample,passingcloudscandisruptDPVoutputandtriggervariationsingridelectricityconsumption.Inturn,thesecanaffectgridvoltage.Hence,planningand16FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVoperationforvoltagemanagementmayneedtofactorinfeed-noneinstallations.Feed-nonearrangementsmayhavenoneedforameterthatmeasuresDPVoutput.However,largefeed-nonearrangementsmightbenefitfrommeasuringoutputtoinformtheuserortohelptheutilityforecastload.Systemsdesignedforusewithoutthegridtypicallyalsohaveabattery,chargecontroller,andaswitchtodisconnectthedirectcurrent(DC).FIGURE2:TYPESOFARRANGEMENTSFORDISTRIBUTEDGENERATIONFEDINTOTHEGRIDFd-llFd-somFd-nonAlldistributdnrtionisSomdistributdnrtionisAlldistributdnrtionfdtorid.fdtorid,somisforslf-suppl.isforslf-suppl.Thisrequiresseparate(gross)NetmeteringorgrossThisisoftenpairedwithabatteryormetersforproductionandotherbackup.Productionmayormayconsumption.meteringarepossible.notbemetered.Source:Originalfigurebytheauthorsforthisreport.DPVsystemsthatfeedsomeorallelectricitytothegrid,connect(orinterconnect)withthebroaderdistributionnetworkthroughabuilding-levelservicepanelonsmallersystemsorthroughadedicatedtransformerinlargerinstallations.Meterstypicallyserveasthepointofcommoncoupling,wheretheDPVsystemconnectstothegrid.AfterinstallationofaDPVsystemthatfeedsthegrid,inmostcasesinspectionandapprovalfromthedistributionutilityisrequiredpriortocommissioning.Connectionstandardsinelectricalgridcodesinformrooftopinstallationcompaniesontechnicalspecificationsandsafetyfeaturesthatmustbemetforfeed-inDPVsystemstobeapproved.ThesearecoveredinChapter3.Connectionstandardsdonotapplyforfeed-nonearrangements,thoughtheymaystillberegulated.DPVthatFeedstheGridhasDistinctImplicationsDPVthatfeedsintothegridchallengestheclassicrulesgoverningdistribution:thatthesubstationisthesolesourceofpowerflowingfromthesubstationtoconsumersdownstreamatfeedersections.Atgrowingsharesoffeed-inDPV,periodsofminimumloadandreversepowerflowsuptohighervoltagelevelsbecomeimportant.LowdemandperiodscancoincidewithpeakDPVoutputpotential,suchasonresidentialfeedersonweekdaysoratfactoriesthatshutdownatlunchtime.Thiscanleadtopowerflowing(orattemptingtoflow)fromlow-voltagetomedium-voltagenetworks,andevenfromadistributionfeedertothetransmissionsystem.1:HOWIMPORTANTISDPVFORPOWERSYSTEMPLANNERSANDOPERATORS?17Alldistributionsystemsare,technicallyspeaking,bidirectional.Feedingpowerfromageneratoronthecustomerside,athighervoltagelevels,istechnicallyfeasible.ThisissuccessfullymanagedintopDPVmarketsaroundtheworldandisnotinherentlydangerous.Itrequiresnomodifications,althoughinsomecasesitmayrequirechangestoprotectionequipment.InanAC-powersystem,thedirectionofcurrentitself—asimpliedbythename“alternatingcurrent”—alternatesinthesystemconstantly,manytimespersecond.Indeed,thechangeisnotasfundamentalasitmayseem.Nevertheless,reversepowerflowcanproducebottlenecks,dependingontheconditionoftheinfrastructureandassociatedoperationalcapabilities.OptimizingormaximizingtheamountofDPVinadistributiongridwhilemaintaininghigh-qualityserviceandreliabilitycallsforunderstandingthehostingcapacitylimitsandpossibleenhancements.DPVIMPACTSONPOWERSYSTEMSEVOLVEASDEPLOYMENTGROWSDPVhasbeendeployedatalargescaleformorethanadecadeacrossmanydifferentcountriesanddiversegridtopologies.ThisexperiencerevealsvariouswaysinwhichDPVchallengestraditionalpowersystemplanningandoperations.EnergySectorAgenciesNeedtoAnticipateIncrementalImpactsasDPVGrowsDeploymentofDPVhasagradual,incrementaleffectonpowersystems.However,akeyfeatureofDPVisthatitcanbeinstalledrapidly,inamatterofweeks,muchfasterthantraditionalbulkgenerationplants.Inmanycountrycontexts,DPVdeploymentrateshaveexceededexpectations,especiallywhendevelopersandconsumersrespondtoattractivefeed-intariffs.InVietnam,forexample,DPVcapacityincreasedfrom0.4GWpeakto9.3GWoverthe12monthsof2020,withanestimated6.7GWconnectedinDecemberalone.4Proactivelyaccountingforthelikelihoodanduncertaintyofahigh-growthscenarioisthusimportant.DPVdeploymentprojectionsalsoneedtoconsiderinteractionswithothertrends.Growthinelectricvehicles,forexample,mayincentivizeDPVindependentlyoffeed-intariffs.Historically,DPV’smainproblemsstemfrombeingunderestimated.Earlymanagementstrategieswerenotwellpreparedforrobustdeploymentsafewyearslater.Awell-designedDPVprogramshouldbestrategicfromtheoutset.Suitableattentiontoplanningmustthereforealsobepartofthecapacity-buildingsupportsoughtforutilitystafftofamiliarizethemwithDPV.DPVsharespropertiesofothervariablerenewableenergy(VRE)technologies,namelylarge-scalePVandwind.Forthisreason,itisimportanttoconsiderthedeploymentofDPVfromboththeperspectiveoflocaldistributiongridsaswellasoverallbulkpowergenerationresources.Inbroadterms,levelsofpenetrationcanbedistinguishedbytheshareofthepowersystem’sgrossannualelectricitygenerationcomingfromDPVonitsownorincombinationwithotherVRE.Lowpenetrationiswhenthisratioisnomorethanafewpercentagepoints.Atthislevel,effectsofDPVdeploymentareusuallylocalizedandrelateonlytothedistributiongrid.CertaindistributionfeedersmayencounterhighsharesofDPV(i.e.,nameplateDCpanelcapacityismultipletimesthefeederpeakcapacity),althoughDPVisnotyetasignificantcontributortotheoverallpowersystem.Mediumpenetrationmaybewhentheshareissomewhereintherangeof5to10percent,atwhichpointseffectsmaybeseenthroughoutthepowersystem.Highpenetrationcanoccuraround10percent,atwhichthresholdtheremaybeseveral4Vietnam’s25-foldincreasewasspurredbyatime-limitedprogramofgenerousfeed-intariffs,rangingfrom7.00to9.35UScentsperkilowatt-hour(kWh),with20-yearcontracts(Leandothers2022),thoughtherushofinstallationscontinuedafterthefeed-intariffdeadlinehadexpired(Le2022).Theunplannedboom,whichalsoinvolvedbulkrenewablepowerplants,ledtogridinstabilityandcurtailment(WBG2022).18FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVoccasionsduringtheyearwhenVREprovidesmorethan50percentoftheloadoveratleastonehour(Holttinen2018).Specificthresholdsdependonpowersystemcharacteristicsandcanvarygreatly.Differenttechnicalissuesareassociatedwithlow,medium,andhighlevelsofpenetration.Theseissuesaredescribedbelow,whilesolutionstoeachoftheseissuesarepresentedsubsequentlyinChapter2.ThereareimportantimplicationsforsystemoperationonceDPVgeneratesreservepowerflowsfrequentlyandinseverallocationstothetransmissionlevel.Broadlyspeaking,DPVcapabilitiesmustbematchedtoDPVreliability.ThegoalistoguaranteeDPVgenerationthatsystemoperatorscanseeandcontrol.Moreover,DPVneedstoprovidemoresystemservicesathigherpenetrationlevels.LowDPVpenetration:VoltageissuesTheearliestcommonrisktoariseisthebreachofvoltagelimitsofadistributionfeeder.VoltageissuesmayoccuratearlystagesofDPVdeploymentevenbeforeDPVoutputexceedslocaldemandonagivenfeeder,forreasonsexplainedbelow.Voltageissuesmayalsooccuratsubsequent,higherpenetrationlevelstoo.Inruralgridareasoratweakgridconnectionpoints,DPVatlowpenetrationlevelsmayalsocauselocaloverloadingorpowerqualityissuesasaddressedundermediumandhighpenetrationlevels,furtherbelow.Ageneralfeatureofdistributionfeeders,withoutDPV,isthatcustomersfarfromadistributiontransformerreceivepoweratalowervoltagethanthosenearthetransformer.Thisisbecausevoltagelevelalongafeederdecreaseswithdistancefromthetransformer,allthemoresowhenelectricitydemandishigh.InFigure3,thelower(black)lineshowsvoltagedeclinealongaradialfeederwithheavyloadsandnoDPVoutput,asFIGURE3:VOLTAGEALONGARADIALFEEDERUNDERDIFFERENTCONDITIONSOFLOADANDDPVOUTPUTFEDTOGRIDUpperDaytimelightloadvoltageincreasesvoltagewithdistancefromtransformerlimitFeedervoltageLowerEveningheavyloadvoltagevoltagelevelsdecreasewithdistancefromtransformerlimitDistributionLoadsonfeederatincreasingdistancefromdistributiontransformertransformerSource:Originalfigurepreparedbytheauthorsforthisreport.Note:Theconsumerfurthestfromthetransformer(farrightofthefigure)risksovervoltageattimesofhighloadandlowDPVoutput,andrisksundervoltageattimesofhighDPVoutputandlightload.ThisfigureassumesDPVwithoutuseofstorageordemandresponsemechanism.1:HOWIMPORTANTISDPVFORPOWERSYSTEMPLANNERSANDOPERATORS?19mightoccuronatypicaleveninginaresidentialarea.Voltagedropsareevenmorepronouncedinlocationswhereimpedanceishigh,forexamplewhenthediameterofconductorcableissmall.Inruralareaswithradialfeeders,voltageatthedistributiontransformeristhereforesetatthehigherendoftheallowedrange,ensuringthatsufficientvoltagereachesthefurthestcustomerunderheavy-loadconditions.Box2explainsradialversusothertypesofdistributionfeeder.AddingDPVtolongfeederscanexacerbatevoltageissues.ForDPVfeed-inarrangements,theDPVinverter“lifts”thevoltageatthepointofinterconnection,sothatelectricitycanfeedthegrid.Anyliftingeffecthasarangeofconsequences,whichmaybegoodorbaddependingonloadconditions.Iftotalloadfromlocalconsumptionishigh(matchingorexceedingDPVfedintothegrid),thenthevoltageattheDPVinstallationlocationwillberelativelylow.Inthiscircumstance,DPVfeed-inmightevenimprovevoltagelevelsbyraisingthemtothetargetlevels.However,problemsmayariseiflocalconsumptionislow—i.e.,whenDPVelectricityisbeingfedallthewaybacktothesubstationtransformer.Insuchcases,voltagesurgecanbesignificantwithariskofviolatingvoltagelimitsonthefeeder(see,e.g.,Bazrafshanandothers2019;Islamandothers2017;Palmintierandothers2016).InFigure3,theupper(orange)lineshowsthefeedervoltagelevelincreasingateachsitewithDPVwhenloadsarelight,asmightoccurinthedaytimeforaresidentialarea.Voltageproblemsareriskierforlongradialfeederswithgrid-feedingDPVsystemslocatedfarfromthedistributiontransformer.MediumDPVpenetration:AdditionalissuesAtmediumlevels,thermallineratingsandtransformercapacitiesmaybecomeconstraints.Additionalissuesmayinclude:maintainingfaultprotectioncapability;copingwiththevariabilityofnetload,whichwillexhibitsteeperandlargerrampsduringmorningandeveninghours;copingwithoutputuncertainty,asforecastsforBOX2RadialversusOtherTypesofDistributionFeederThetopologyorlayoutofdistributionfeedershasimplicationsfortheeffectofaddingDPV.Distributiongridsreceiveelectricityfromthehigh-voltagetransmissionsystematsubstationswheretransformerssteptheelectricitydowntolowervoltages.Eachsubstationtransformertypicallyfeaturesseveralcircuits,orfeeders,whichuseprimarydistributionlinestosupplyelectricitytoneighborhoods.Feedersindistributionsystemsmayhaveradial,spot,looped,ormeshconfigurations.•Radialnetworksaretree-likestructures,withthehigher-voltagepoweremanatingfromthetrunk,atthebaseofthecircuit,whileprimaryfeedersemanatelikebranchesfromthesubstation.Theyoperateonasinglepathofcurrent.Radialsystemsaretypicallyusedforlight-andmedium-densityloadssuitedtoresidentialandsmallcommercialconsumers.However,incountrieswithaweakgridenvironment,largerloadsmayalsobeconnectedviaradialsystems.•Spot,looped,andmeshednetworksdeliverconcentratedorhigh-densityloadstypicalincitiesandforfacilitiesthatneedhighlyreliablepower,suchashospitals.Thesenetworksprovideredundancybyhavingmultiplesourcesofsupplythroughaseriesofconnectedservicetransformers.20FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVFIGURE4:RAPIDEVENINGDROPINDPVGENERATIONWITHRAMPUPOFOTHERSOURCES,AUSTRALIANEXAMPLE35,000Solar(rooftop)13.4%30,000Solar(utility)7.5%25,000Wind8.5%20,000Hydro7.2%15,000Battery(discharging)0.1%10,000Othergasandoil0.6%Gas(opencycle)1.6%5,000Gas(combinedcycle)4.1%0Coal(black)43.6%Coal(brown)14.0%Pumps–0.5%Battery(charging)–0.1%–5,0000123456789101112131415161718192021222324Tues21DecSource:AustraliaNationalElectricityMarket,dataforDecember21,2021(McConnellandothers2021).PVoutputcanbedoneonlyafewdaysorhoursbeforehand;andcopingwithexceptionalconditionssuchasvoltagedips.TheseissuesarepracticallyidenticaltothoseobservedwithlargeamountsofbulkPVorwindgeneration.Byreducingoveralldemandforgridelectricity,DPVcandramaticallychangeloadcurvehourlypatterns.Thisistrueevenforbackuparrangementsthatfeednooutputtothegrid,andhasimplicationsforplanningofbulkgenerationandnetworkinfrastructure,aswellasforcostrecovery.5HighpenetrationratesofDPV,regardlessofthefeed-inarrangement,typicallyleadtohigherrampsbetweenpeakandoff-peakloads.Thispointstotheneedformoreflexibilityinthepowersystematlargetocopewithabruptchangesinnetload.Theresultingloadshapeisoftenreferredtoasthe“duckcurve,”whichcanalsobeseeninrelativelylargesystemswithutility-scalePV.Forexample,inAustralia,whichhassomeofthehighestDPVpenetrationlevelsintheworld,DPVisshapingthemainnationaltransmissiongridloadcurveandtechnicaloperations.Figure4illustratesanactualsummerdayinAustralia’smainelectricitynetwork,wherearapideveningdropofDPVgenerationismatchedbyarampupinothersources.AsDPVchangesthepatternsofdailyloadcurvesforgridelectricity,demandbecomeshardertopredict.Thischallengecanbeallthemoredifficultwhenpowerflowsbecomebidirectional5ThethirdreportinthisseriesdiscussesbroaderimplicationsofDPVforpowersectorfinancialviabilityanddifferentbusinessmodels.1:HOWIMPORTANTISDPVFORPOWERSYSTEMPLANNERSANDOPERATORS?21orwhenconsumersactivelymanagedemandtoreduceelectricitybills.Rulesofthumbandindustry-standardcalculationshistoricallyusedtoinforminvestmentdecisionsarethusbecomingoutdated.Advancedcommunicationinfrastructure,suchasSCADA6connectedtodistributedenergyresources(DER),canhelp.HighDPVpenetration:LesscommonissuesAttheextreme,DPVorothervariablerenewablesmaygeneratemostofthepoweratsometimes.Insuchcases,additionalissuesmayarise:powerquality;andlackofsynchronousgeneration.TheseissuesaremostlyrelevantforsmallpowersystemsandrarelyaconstraintforDPVuptake.HighpenetrationofDPVmayaffectpowerqualitybyintroducingharmonics.Thiscannegativelyimpactsensitiveequipmentincludingthatofothercustomers.Second,DPVisaninverter-basedgenerationtechnology,connectedtothegridviaelectronics,asdistinctfromthermalandhydropowerplants,whichhavemotorsthatdirectlyproducealternatingcurrent(AC)electricity.Motors’frequencyofrotationcanbesynchronizedwiththepowerofelectricitytransmittedanddistributedthroughoutthegrid.Forthisreason,thesetypeofpowerplantsareknownassynchronousgenerators.Ahighshareofinverter-basedgenerationcanaffectthestabilityofgridelectricityifnotaccompaniedbysolutionstocompensateforthelackofsynchronousgeneration.HostingCapacityforDPVisaDynamicConceptHostingcapacityhererefersbroadlytotheestimatedmaximumamountofdistributedgenerationthatcanbeintegratedintopartofanelectricalnetworkwhilekeepingwithinoperationalperformancelimits,beforeorafterenhancementtechniques.HostingcapacityisacriticalconceptforDPVandotherformsofdistributedgenerationthatfeedintoagrid.Itisrelevantforthepurposeofplanning,gridcodeconnectionscreeningandapprovalprocedures,andpowersystemoperation.Theconceptofhostingcapacity,firstintroducedin2004,hasseenstarklydifferentapplicationsacrosscountriesovertime(Ismaelandothers2019).Importantly,hostingcapacityisparticularforagivenpowersystematapointintimeandspace.Itisnotonefixedexactvaluebutratherdeterminedbyaprobabilisticrangeofperformanceindices(e.g.,overvoltage,thermaloverloading,powerquality,protectionproblems).Thisindexvaluescanvarybylocation(nodesandfeeders)andbyenhancementtechniques(e.g.,reactivepowercontrol,voltagecontrol,activepowercurtailment,energystoragetechnologies,networkreconfigurationandreinforcementandmitigationofharmonics).Itisthereforeimportanttoconsiderwhyandhowtodefinehostingcapacityinagivencontexttoapplytheconceptinpractice.Chapter2discussesenhancementtechniques,whileChapter4discussesapproachestohostingcapacityanalysisinthecontextofpowersystemplanning.6SCADAreferstosupervisorycontrolanddataacquisition,asystemofinformationandcommunicationtechnology,withhardwareandsoftware,toassistsystemoperatorstoautomateandmanagethenetwork.22FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPV2:TECHNICALSOLUTIONSFORGRID-FRIENDLYDPVPowersystemsaredesignedandoperatedwithageneralobjectivetoinstantaneouslymatchdemandforelectricityacrossthegridbyadjustingbulkelectricitysupply.Naturally,therearetechnicalandeconomiclimitstoachievingthisobjectiveinfull,especiallyinmanyLMICs.Powersystemshavethusevolvedvariousmechanismstohelpcoordinatesupplyanddemandandtocopewithimbalancesthatoccurovertimeinsomepartorallofthegrid.SimilarprinciplescanbeappliedtomanageDER,withcertaindifferences.ThischapterexploressuchsolutionsforDPV.CharacterizingPotentialTechnicalSolutionsforGrid-FriendlyDPVAwiderangeofpotentialtechnicalsolutionsexistforgrid-friendlyDPV.Thesecanbecharacterizedintermsoftwogeneralapproaches:1.Localload-balancing.ThistypeofinterventionseekstomatchDPVsupplyandlocaldemandwitheachotherasmuchaspracticaltohelpkeepgridswithinagivenhostingcapacityorspecifiedsystemoperatinglimits.Theaimoftheseinterventionsistokeepnetload7relativelystableandcertain,akintoloadconditionswithoutDPVoreven,ideally,toimproveuponthem.Suchinterventionscanthushelpdeferorreduce,ifnoteliminate,thesizeandfrequencyoflocalimbalancesthatriskproblemsforthegrid.2.Hostingcapacityenhancement.Evenwithloadbalancing,therewillbeaneedforDPVsystemsandthepowersystemtocopewithchangedgridconditionsresultingfromdeploymentofDER.Keyoptionstothisendinclude:DPVinverterprogramming;gridequipmentadjustmentsandupgrades;andenhancingoverallflexibilityofthepowersystem.Thischapterdescribesamenuofexamplesolutionsundereachofthesetwocategories.Somesolutionsareintroducedbrieflywhileothersareelaboratedinmoredetail,basedonavailableinformation.Underbothcategories,differentsolutionscanbeimplementedatdifferentlevelsofthepowersystem,namely:designandoperationofDPVsystemsthemselvesontheconsumersideorgridside;localdistributiongrids;and,insomecases,thepowersystemoverallincludingbulkgenerationandtransmission.Inverters(withinDPVsystems)areemphasizedgiventhewiderangeoflow-costsystembenefitstheycanprovide,whichremainasyetlargelyuntappedinLMICs.WhichsolutionsarerelevantforagivencontextdependsonlocalconditionsincludingthecurrentandfuturelevelofDPVpenetration,notingactualgrowthratesoftenexceedexpectations.Grid-friendlyDPVsystemscanavoidormitigatenegativeimpactsonthegridinthefirstplace,andreducetheneedforotherfixesatthepowersystemlevel.DevelopersofDPVsystemprojectsusuallybasedesignsontheimpactforhostconsumersratherthanforthepowersystem.Certaindesignfeaturescan,however,affectlargeindividualsitesandpowersystemsgenerally.Tomaximizesynergies,developerscanbeencouragedtoconsiderpowersystemimpactsofDPVsystemdesignsinaggregateandforlargeindividualprojects.7Netloadherereferstogrossdemandforgridelectricitylessdemandservedbydistributedand/orbulkvariablerenewablesources,alsoknownasnegativeloads.23TableAsummarizestechnicalsolutionsforDPVbymappingissuesthatariseacrosslowtohighpenetrationlevelsandtheiroperationalandplanningorinvestmentsolutions.8Solutionshighlightedinitalicsinvolveload-balancing,whileothersaimtoenhancehostingcapacity.Someissuesaffectthedistributiongrid,whileothersconcernthepowersystematlarge.Costisnaturallyakeyconsiderationinassessingdifferentsolutions.Ingeneral,incrementalDPVsolutionsusuallyhavelowtomoderatecostswhenplannedahead.Highcostsresultfromneedingtoreplaceassetsbeforetheendoftheireconomiclifetime.Figure5illustratesthepotentialrangeincostofsolutionsforissuesthatmayaffectthedistributiongrid,ifnototherwiseavoided.Attheleveloftransmissionsystems,requirementsforforecasting,visibility,andcontrollabilityofbulkPVcanbeappliedtoDPVinaggregate.GeographicdispersionofDPVsystemsshouldtend,ontheonehand,tomakeaggregateoutputsmootheratthesystemlevelthanafewsiteswithalargeconcentrationofDPV—easingintegration.Ontheotherhand,theaccretionofmanyindividualplantscanhampervisibilityandcontrollability—complicatingintegration.Apragmaticapproachcouldbetoprioritizevisibilityforallbutthesmallestinstallations,whileensuringcontrolasrequired.SOLUTIONSMENU1:LOCALLOADBALANCINGSupply-DemandCoordinationOptionstocoordinatedistributedresourcesincludethefollowing.(a)�AvoidoversizedPVcapacityforself-consumptionbyensuringlocalenergyefficiencyopportunitiesareidentifiedbeforedesignandapprovalofDPVsystems.Indoingthis,accountforpotentialnewsourcesoflocalelectricitydemandfrombuildings,industrialprocessesandvehicles.(b)AnalyzehostingcapacitiesofnetworklocationstoinformDPVsitingandchoiceofoptimaldesignparameters.IdentifynodesorfeederswhereDPVcouldhelpeasecongestionwithorwithoutstorage.(c)FavorinstallationoflargeDPVsystemsclosetodistributiontransformerstohelpmitigatevoltageproblemsalonglongfeederswhereloadsareinflexible;(d)UsedigitaltechnologiessuchassmartmetersandinverterstoenhancemonitoringandcontrolofDER.(e)AggregateDERintovirtualpowerplantsorlocalbalancingareas.CoordinatingDPVtoprovidesystemservicesBydefault,bulkpowerplantsarerequiredtoprovidesystemservicestomaintainvoltageandfrequencywithinnominalrangesatalltimes(viaresponsecharacteristicsandreserves);theyalsoprovidecapabilitiestorestartthepowersystemfollowingalarge-scaleblackout.UsingDPVtoprovidesystemservicesistechnicallypossiblebutrequiresefficientcoordinationofacomparativelylargenumberofresourcestodoso.Theproblemcanbesolvedthroughtheapplicationofinformationandcommunicationtechnology.Thiscanbecost-effectivebyremovingtheneedforbulkpowerplantstoremainonthesystemandallowingDPVtosubstitutefortheirgenerationatzeromarginalcost.Putdifferently:DPVissometimescurtailedinfavorofmoreexpensivegenerationthatcanprovidesystemservicesmoreeasilyundercurrentconditions.AvoidingDPVcurtailmentmayhaveeconomicbenefitsthatoutweighthecostsofenablingsuchfunctionalities.Thiscanbeachieved,forexample,byaggregatingDPVinstallationsintoavirtualpowerplant(Box3).Invertprogrammingforsystemservicesisdiscussedfurtherbelow(page30).8SeeChapter1foranexplanationoflow,medium,andhighDPVpenetrationlevels.24FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVTABLEA:POWERSYSTEMSOLUTIONSTODPVISSUESFROMLOWTOHIGHPENETRATIONRISKISSUEOPERATIONALSOLUTIONPLANNINGORINVESTMENTSOLUTIONLowpenetration•ProgramDPVinverterstocontributetogridvoltage•PromotematchingofDPVVoltagelevels.DPVcanraisemanagementoutputandloadthroughlocalvoltagelevelsattimessupply-side,demand-side,andwhenPVoutputishighandlocal•Adjustexistingvoltagecoordinationinterventionsdemandislow.Thismaycausecompensationequipment,voltagelevelstoexceedallowedincludingtransformersettings•Installon-loadtapchangingmaximumvalues.transformerstoactively•ReconfiguresettingsofexistingmanagevoltageinrealtimeMediumpenetrationprotectionschemes•UpgradeprotectionschemestoFaultprotection.DPVmay•Dynamicallycurtailfeed-inimprovefunctionalityimpacttheefficacyofschemesduringtimesofsystemstress(iftoprotectthespreadoffaultsinsystemsaretechnicallycapable•PromotematchingofDPVdistributionnetworks.todothis)outputandloadTransformercapacitiesand•Incentivizedemandresponse•Plan,andifneededupgrade,conductorthermalratings.DPV•AggregateDPVintotransformersandconductorsoutputfedtogridmayincreasewithhigherratingspowerflowsinthedistributiongridcontrollable,virtualpowertothepointofoverloadingthermalplants•Increasepowersystemratingsandtransformercapacities.•Dispatchotherpowerplantsflexibility(demandresponse,moreflexiblystorage,flexiblegeneration,OutputvariabilityAcrossthe•ForecastDPVoutputandautomatesystemoperationspowersystem,netload(i.e.,measurereal-timeoutputatwithdigitaltechnologies)powerdemandminusDPVoutput)enoughDPVsitestoinformwillexhibitsteeperandlargersystemoperations•LimitrapidDPVoutputchangesramp-upsduringmorningandusingenergystorageeveninghours.•UseDPVinverterstoprovidelow-voltageride-throughand•EnsuregridcodesrequireOutputuncertainty.Acrosstheothersystemservicesinverterstohavethecapabilitypowersystem,accurateforecastsforhighDPVsharesofDPVoutputcanbeobtained•Maximizeuseofexistingonlyafewdaystoafewhoursinverterstosupportpower•Installharmonicfiltersandotherbeforehand.qualitypowerqualitymanagementequipmentExceptionalconditions(e.g.,•Adjustharmonicfiltersandothervoltagedips)inthepowersystem.powerqualitymanagement•Usegrid-forminginvertersDPVmustbehaveinawell-equipment•Installsynchronouscondensersdefined,system-friendlywayduringgriddisturbances.•Introducefast-actingreserveservicesHighpenetrationPowerquality.DPVmayaffectpowerqualityindistributionnetworksbyintroducingharmonics,whichcannegativelyimpactsensitiveequipmentincludingthatofothercustomers.Lackofsynchronousgenerationinthepowersystem.DPVconnectstothegridviapowerelectronicsratherthanasynchronousgenerator.Note:Texthighlightedinitalicsindicatesload-balancingsolutionsthathelpmatchDPVoutputwithlocaldemand.Incontrast,othersolutionsaimtoenhancehostingcapacitybyadaptingsystemstocopewithchangedgridconditions.Case-by-caseappraisalisimportantforthedesignandcostofanyintervention.2:TECHNICALSOLUTIONSFORGRID-FRIENDLYDPV25FIGURE5:DISTRIBUTIONGRIDEFFECTSFROMDPVBYLEVELOFPENETRATIONANDCOSTRANGEOFSOLUTIONShighThermallineratingandtransformercapacityPotentialcostofVoltagelevelsolutionFaultprotectionPower(ifissueisnotqualityotherwiseavoided)highlowLevelofDPVpenetrationinpowergridlowSource:Originalfigurepreparedbytheauthorsforthisreport.Note:Thisfigureisindicativeandbasedongeneralexperienceacrosscountries.Specificcostsofdifferentinterventionswillvaryfromcountrytocountryandshouldbeassessedcasebycase.Supply-SideAdjustmentsOnthesupplyside,DPVsystemscanbedesignedandoperatedtobetteralignwithlocalloadpatterns.Supplysidesolutionsmayincreasegenerationcostssomewhat,soconsiderthecostsandbenefitofintroducinggeneralrulesonthis.Optionsincludethefollowing.(a)CalibrateDPVpanelsizesandanglestoserveknownpeakloadsandtodiversifypeakproductiontimes.(b)SizeaPVarray’sDCcapacitytoexceedtheinverter’sACcapacityforanoptimalDC:ACratio(greaterthanone),sopeakoutputisclippedwhileoutputduringnon-peakperiodsismaintainedormaximized.(c)SizeDPVsystemoutputcapacitytoserveonlyefficientlocalenergydemandwhileaccountingforpotentialnewsourcesofdemandsuchaselectricvehicles.(d)Limitfeed-inthroughdynamiccurtailmentorarrangementsthatfeednoneoftheoutputtothegrid.OptimizingDPVpanelsizesandanglesacrossthegridThesolarPVarrayistheprimarycomponentofaDPVsystem.Itcomprisesoneormoremodules,orpanels,thatconvertincidentalsunlightintoDCelectricity.Generallymountedasfixedpanels,DPV26FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVBOX3AggregationofDPVintoVirtualPowerPlantsAvirtualpowerplant(VPP)isanaggregationofvariousdistributedenergyresources(DER),usinginformationandcommunicationstechnologytoprovidepowersystemoperatorswithserviceslikethoseprovidedbyabulkpowerplant.Butinformationandcommunicationtechnologywoulddelivertheseserviceswithgreaterprecision,flexibility,andefficiencythanindividual,uncoordinatedDERs.VPPshaveanimportantroletoplayinafuturethatfeaturesgreaterpenetrationofDPVtechnologies.Also,VPPswouldeaseplanningforthedispatchablegenerationorsystem-levelreservesrequiredtobalancevariablerenewableenergy.AVPP’sobjectivesusuallyarisefromthesystemormarketenvironmentinwhichitoperates.AlthoughVPPsarerelativelynew,commercialinitiativeshavealreadyemergedintheUnitedStates,Australia,andEurope.In2019,thecompanySunrunwonthefirstcontracttosupplycapacitytotheUSwholesalepowermarketfromaVPP,providing20MWofcapacityfromsolarenergyandstorageaggregatedfromhomes,viatheIndependentSystemOperatorofNewEngland’sForwardCapacityMarket.InAustralia,theAustralianEnergyMarketOperator(AEMO)conductedademonstrationprojectforVPPsfrom2019to2022.Althoughparticipationwasopentoanytechnology,allregisteredVPPsusedbatteriesintheirportfolios.Variousstate-basedincentivesprogramcollectivelytargetedupto700MWofVPP-capableresidentialbatterystorageby2022.AsofJune2021,almost168MWacrossabout31,000connectionshadregistered.TheprojectdemonstratedVPPs’capabilitytodeliverfrequency-controlancillaryservicesandothersupporttothegrid,andinformeddeterminationofamarketancillaryservicesspecificationin2021.Sources:MicrogridKnowledge(2019);AEMO(2021),andMaisch(2019).SeealsoIEA(2022c)forrecommendationsonmarketdevelopmentopportunitiesforDERsmoregenerally.modulesareinstalledatafixedangletocapturesolarirradiation.9Afixedpanelmaybemounteddirectlyonasurface,iftheangleofthatsurface(e.g.,atiltedroof)issuitable,ormountedonframesallowingthepaneltobesetatadifferentangle.Panelpositionshaveimplicationsforthepowersystem.PowerdensityisalwaysgreatestwhenthePVpanelisperpendiculartothesun.Butpanelscanstillgenerateelectricityfromdiffuseandindirectirradiation.Bifacialpanelscancapturesunlightfromeitherside,afeaturewellsuitedtosolar-reflectiverooftops,wherethepanelshelpbuildingswithpassivecooling(ESMAP2020a).9PVsystemscanalsobedesignedtomovealongoneortwoaxeseithermanually,e.g.,twiceayeartooptimizeforseasonalvariation,orautomaticallytotrackthesunoverthecourseofeachday.TrackingarrayshavehighercapitalandoperationalexpensesandoccurrarelyinDPVinstallations.2:TECHNICALSOLUTIONSFORGRID-FRIENDLYDPV27Inmostcases,panelangles(orientationandtilt)arechosentomaximizetotalannualenergyproduction.Thismeanpositioningpanelsforpeakproductiontooccuraroundnoon(i.e.north-facinginsouthernlatitudesandsouth-facinginnorthernlatitudes).Thisapproachnaturallysuitstheleast-costgenerationandbillreductionusecases,iffeedinisallowed.However,ifallDPVsystemsinadistrictpeakatthesamehourofaday,theiraggregateeffectonnetloadpeaksandtroughsismagnified.Theriskofsupply-demandimbalanceinthissituationmaybemoderateifpeakdemandinthosedistributionfeedersalsooccursaroundnoononaverage(e.g.,commercialbuildingswithhighcoolingneedsaroundnoononsummerdays),orifdemandcanbeflexiblyshiftedtomatchthehourofpeakproduction(e.g.,airconditionersprogrammedtoincreaseworkearlierthantheymightotherwisetocoolbuildingsefficientlyinadvanceofpeakcoolingdemand).Alternatively,panelscanbeorientedwithaneastwardorwestwardbiastoshiftpeakpoweroutputtothemorningsorevenings,tomatchtheaveragehourofpeakdemandonsiteoronthelocaldistributionfeeder.Inotherwords,panelpositioncanbedesignedtoreflectthetimevalueofproduction.Forexample,whenDPVdesignanalysesrevealthermaloverloadingofdistributionlines,otherpositionscanbeexploredtoyieldamoreconsistentoutputprofile.Whileorientingsystemseastorwestcanresultinlowertotalannualoutputsthaninstallations,thetrade-offcanbeconsideredstrategicallybyDPVsystemdesigners,ideallyincoordinationwithdistributionsystemplannersandoperators,andreflectedinconnectionstandardsandincentiveprograms.SizinginvertersforahighDC:ACratioAlmostallDPVsystemsdeliverDCpowerthroughelectricalcablestoaninverter,whichisasoftware-controlledpowerelectronicsdevicethatchangestheDCelectricityinputtoanACoutput.10InvertersmaybewiredtoPVpanelsindifferentways:(i)asinglePVpanelmayhaveitsowninverter,knownasa“microinverter”;(ii)morecommonly,alineofPVpanelstogetherfeedoneinverter,knownasa“stringinverter”;(iii)insomelargeinstallations,anarrayofseveralPVpanellinesmaybeservedbyasingle“central”inverter.DPVsysteminvertersinvolvetwokeydesignparameters:•DC:ACratioofinvertercapacityrelativetothePVarrayoutput,discussedbelow;and•Programmableelectronicfunctionsofinverter,discussedlaterunderhostingcapacityenhancements.TheDC:ACratio,alsoknownasinverterloadratio(ILR),istheratiooftheDCcapacityofaPVarray’speakoutputtotheACoutputcapacityofitsinverter.Thecostofinvertersincreaseswiththesizeoftheircapacity.Assuch,systemsaregenerallydesignedtousethesmallestappropriateinvertercapacity,allelsebeingequal.PVsystemsgenerateoutputattheirpeakDCcapacityonlyforsomehoursofanygivenyear,andlessthan1percentoftheenergyproducedwillbeatapowerabove80percentcapacity(Pulumbarit2023).Assuch,itisoftennotcosteffectivetosizeanACinvertertocaptureallofthePVoutput,i.e.,withaDC:ACratioofaround1,unlessmorePVcanbeconnectedtotheinverterinthefuture.AnoptimalratioforDPVsystemsmaybeintherangeofaround1.1to1.5orevenhigherdependingonthespecificcircumstances.11AsystemwithahighDC:ACratio(>1),andnoDC-connectedbatterystorage,10DCoutputfromPVpanelscan,inlimitedcases,beuseddirectlyforDCloadsorcircuits,andforcertainisolatedsettingssuchasruralmicrogrids(Tomar2020;Papadimitrouandothers2018;Hailuandothers2015).ButDCcircuitsandgridsarenotcommon.Forpracticallyallelectricitygrids,largeandsmall,andforconsumercircuits,thestandardisAC.Invertersarealsoknownasconvertorsinsomecountriesandinsomeliterature.11Invertersaretypicallylessthan100percentefficient.ThisshouldbetakenintoaccountwhenconsideringtheDC:ACratio.Indifferentliterature,thepracticeofdesigningsystemswithaDC:ACratiogreaterthan1maybeknownvariouslyasinverterclipping,peakshaving,overclocking,overloading,oversizing(ofPVrelativetoinverter),orundersizing(oftheinverter).Someliteraturealsoexpresstheratioasapercentage.28FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVshavesorclipsPVoutputduringtimeperiodsofpeak(potential)production(Figure6).However,itdoesthiswithoutconstrainingsolargenerationattimesofnon-peakproduction,includingthemorningsandeveningsofdayswithpeakirradiance.Inthisway,PVsizedgreaterthantheinvertercapacitycanincreasenon-peakoutput(seeFigure6).BecausethePVpanelsreachtheirmaximumoutputforalimitedamountoftime,itispossibletohaveastrongreductioninpeakfeed-incapacitywhilereducingtheoverallamountofusefulenergyonlymodestly.Typically,aratioof1.5mayleadtoareductioninannualenergyoutputofjust2to5percent(comparedtoaunitratioinverterforagivenPVcapacity),whilehavingapronouncedimpactonpeakreduction(Pulumbarit2023).ThisapproachcanenhancethedistributiongridhostingcapacityofDPV.ExperiencetodateinvariouscountriessuggeststhatoptimizingtheDC:ACratiocanfacilitatethetotalinstalledcapacityofDPVconnectedtoadistributionfeedertoexceed75percentofthefeeder’speakcapacity,whilekeepingwithinsystemoperatinglimits.CommonpracticeistosettheDC:ACratioashighaspossiblewithoutsignificantclippingloss.However,optimalDC:ACratiosarebestassessedcasebycase.Genericrulesofthumbforinvertersizingmaybeinaccurateorincorrectastheydependonanumberofparameters.Theseinclude:thesystem’slocation,arrayorientation,size,feedarrangement,technologycosts(modules,inverter,storage),voltagelevel,andfeederreactivepowersupportneeds.Thetimeresolutionofanalysisalsomatters(10-minuteintervalscanprovidesignificantlymoreaccuracythanhourlyintervals).NREL’sPVWattsoftwaregivesadefaultFIGURE6:PVSIZEDGREATERTHANTHEINVERTERCAPACITYCLIPSPEAKBUTINCREASESNON-PEAKOUTPUTKilowattB+C:OutputofPVsizedlargerthantheInvertercapacity(kWDC)inverter(withclipping),additionaltoAD:ClippedoutputofPVsizedlargerthantheinverterBA:OutputofPVsizedCthesameasinverter(noclipping)MorningMiddayEveningHoursofDaySource:Originalfigurepreparedbytheauthorsforthisreport.Note:Thelowercurve(areaA)representspoweroutputonadayofpeakproductionforaPVsystem(withoutbatteries)whereallDCoutputisinvertedtoACoutput,i.e.,DC:ACratiois1(disregardinginverterefficiency).TheuppercurverepresentsadditionalpotentialoutputofalargerPVsystem.Withthesameinvertercapacity,thisresultsinaDC:ACratioexceedingone:peakoutputisclipped(areaD),whilenon-peakoutput(areasBandC)isunconstrained.2:TECHNICALSOLUTIONSFORGRID-FRIENDLYDPV29ratioof1.2.12Anoptimalratiomaybehigherthan1.2forlargerPVplants,systemswithDC-connectedstoragetostorepeakoutputthatwouldotherwisebeclipped,andplantswithnon-orthodoxangles.13Settingfeed-inlimitsOnewaytomatchloadistocurtailDPVoutputduringtimesofhighoutputandlowload.Therearedifferentwaystodocurtailment.Thesimplestsolutionisastaticfeed-inlimit,suchasafeed-nonearrangement,oracapsetaspartoftheconnectionagreement.Inexpensiveinverterscanbeprogrammedtodispatchbattery-equippedDPVatsettimestoensuresmoothsystemoperations.Thissolutionhasbeenappliedeveninlow-incomecountriesmarkedbyfragility.However,thiscanalsobesimplistic.Astaticlimitisgenerallybasedonaworst-casescenariothatmayrarelyoccur,resultinginunnecessarycurtailmentandmissedopportunitiestofeedthegridduringtimesofdayortimesoftheyearwhenmoredistributedgenerationisdesirable.Amoresophisticatedsolutionistousecontrolsystemstocurtailoutputdynamicallywhenneeded.ThisisfurtherdiscussedunderDPVinverterprogrammingbelow.Demand-SideAdjustmentsFlexibledemandcanalsohelpmatchDPVoutputpatterns.Demand-responsemeasurescandirectlyreduceorincreasefinalusesofelectricityatdifferenttimesofdaysasneeded.Furtherflexibilitycomesfromenergystorage:plug-inelectricvehicles;orbatterysystemsconnectedeithertoconsumersordirectlytothegrid.SOLUTIONSMENU2:ENHANCINGHOSTINGCAPACITYDPVInverterProgrammingTheprogrammableelectronicsofinvertersofferarangeofvaluableservices.Thebehaviorandprogrammingofinvertersdeterminehowgeneratorsbehaveonthegridduringnormalandexceptionaloperatingconditions.Inverterscanbeprogrammedtokeepvoltagewithinsystemoperatinglimitsandcopewithexceptionalgridconditionsbyprovidingservicessuchaslow-voltageride-through.Astandardtypologyforinverterfunctionsislackingintheliterature.Figure7capturesasampleoftechnicalservicesthatinvertersinDPVsystemsmayprovide.Here,servicesaregroupedaccordingtothedistributedsystem’scapabilitiesto:(a)controlonlyreactivepower;14(b)controlbothreactiveandactivepower;or(c)additionallyoperateingrid-formingmodetosubstitutefunctionsusuallyprovidedbysynchronousgenerators.DPVinvertersettingsforautonomousregulationinresponsetolocalgridconditionsAutomatedinvertersettingscanturndowntheactivepowerinresponsetolocalfeederconditions.Allmoderninverterscanalsoprovidestaticreactivepower.Whilethisrequiresslightlyhigherinverterratings12NREL(2023).Thistoolgivesadefault3.33ACkWinverterwith4DCkWarrayatstandardtestconditions.13SeeMarcy(2018)andWeaver(2019).AstudyintheUnitedKingdomidentifiedanextremecaseof1.7foranorth-facingPVsystemwithoutstorage(Balouktsisandothers2008).14Reactivepower,measuredinvolt-amperereactive(VAr),isafundamentalfeatureofACelectricity,incontrastwithandcomplementarytoactivepower(measuredinwatts).Reactivepowercanbeinjectedandabsorbedbycertaintypesofelectricalgeneratorsandotherpowersystemequipmentincludinginverters,suchasinDPVsystems.30FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVFIGURE7:TECHNICALSERVICESTHATDPVINVERTERSMAYPROVIDEBASEDONAVAILABLECHARACTERISTICSControlcharacteristicServicesabletobeprovidedReactive1.Compensatereactivepower(staticvoltagesupport)power2.Faultridethrough(dynamicvoltagesupport)control3.Improvepowerquality(e.g.voltageprofile)Active4.Limitfeedintogrid(staticvoltagesupportandcongestionpowermanagement)control5.ProvideoperatingreservesGrid6.Providefirmcapacityformingcontrol7.Systemstabilityservices(syntheticinertia,frequencydroopcontrol)8.Operateasintentionalislandsduringoutages9.SupportblackstartaftersystemwideoutagesSource:Originalfigurepreparedbytheauthorsforthisreport,drawingonStetzandothers(2014).Seealso:Magalandothers(2014),Dingandothers(2020),Linandothers(2020),Kraiczy(2021).Note:Allservicesrequirereactivepowercontrolfromtheinverter.Inaddition,services5through9requireactivepoweroutput,whichcouldbefromPV,battery,oranotherconnectedpowersource.andbooststheelectricityflow(thatis,thereactivepowercomponentoftheflow)onthegrid,itmoderatesvoltageincreasesduetoDPV.Thetechnicalspecificationsinthegridcode(discussedinChapter3)provideonepathwayformandatingtheprovisionofdefaultstaticreactivepower.Someadvancedinverterscanalsoabsorborinjectreactivepowerdynamicallyinresponsetolocalfeederconditions.WhenDPVusegreatlyexceedslocalelectricitydemand,reactivepowerpropertiesmaybeaffected,withcircuitsexhibitinghigherreactivepowerconsumptionduringtheday,owingtohighactivepowerflowsfromDPVgeneration,andmorereactivepowergenerationatnight.Underthesecircumstances,managementofthereactivepowerofthesystemmayrequireadjustment.Inordertoavoidthechallengessurroundingvoltagesurgesduringrapiduptake,DPVconnectionstandardsshouldcontainprovisionsfordisconnectingfromthegridifvoltageexceedsacertainthreshold,addressedininterconnectionstandardsliketheInstituteofElectricalandElectronicsEngineers(IEEE)1547–2018,discussedbelow.WherelargerDPVsystemsareconnectedtomedium-voltagelevelsofthedistributiongrid,theymayberequiredtocontributetodynamicreactivepowermanagement—includinglow-voltageride-throughcircumstances—byremainingconnectedtothegridduringvoltagedips.ThiscapabilitybecomesmoreimportantasDPVpenetratesthesystem.Low-voltageride-throughhasbeenstandardforwindturbinesforoveradecadeandcanalsobeimplementedforDPVusingappropriateinverters.Athighlevelsofpenetration,poorlymanagedDPVsystemsmaynegativelyimpactthefrequencyofACbulkgridpower.Yet,asaninverter-basedgeneration,properlyconfiguredDPVcanactuallyhelpregulatefrequencyandotherdisruptionstothebulkpowersystem.Theresponseoffeed-inDPVtosuchdisturbancesshould2:TECHNICALSOLUTIONSFORGRID-FRIENDLYDPV31beconsideredtoensureconstantgridreliability.Ride-throughcapabilitiesandprotectionsagainstunder-andover-frequency,amongotherproblems,areespeciallyimportantforlargerDPVinstallationssuchasthoseabove30kWcapacity.Evenforsmallersystems,however,frequencyrangesandvoltageoperationsettingsneedtobedefinedandregulated,ideallythroughrevisionsofthegridcode(e.g.,adaptingIEEE1547toreflectlocalcharacteristics),asdiscussedinChapter3.Highpenetrationlevelsofinverter-basedgenerationcallforinnovativefrequencycontrols.MoreadvancedfunctionsofDPVinverters,especiallygrid-formingcontrols,arestillunderdevelopment.Grid-formingDPVsystemsForseveralyearsnow,solar-basedminigridshavebeenrapidlydeployedinremoteareasaroundtheworld.Alsoknownas“third-generationminigrids”(ESMAP2022),theyaregenerallyownedandoperatedbyprivatecompaniesthatleveragetransformativetechnologiesandinnovativestrategiestobuildportfoliosofprojectsinsteadofsingleprojects.Thetypicalthird-generationminigridisreadytobecomegrid-connectedandusesremotemanagementsystems,prepaysmartmeters,andthelatestsolar-hybridtechnologies.Companiesmayincorporateintotheirbusinessmodelenergy-efficientappliancesforproductiveusesofelectricityandprovidereliable,resilient,andhigh-qualityelectricitysupplytousersattheendofservicelines.PuertoRico,forexample,isutilizingsolar-based,third-generationminigridsasafoundationforitsrecoveryfromthedevastationofHurricaneMaria.Theisland’sintegratedresourceplan(IRP)hastakenagridthatwasoncepartofcentralizedgenerationandsegmenteditintoeightminigridsincorporatingPVwithbatteryenergystorage(Siemens2019).SuchsystemsrelyonadvancedDPVtechnology,includinginvertersthatcanfullysubstitutethefunctionsusuallyprovidedbysynchronousgenerators(Box4).GridEquipmentAdjustmentsandUpgradesHostingcapacitycanbemaintainedorenhancedthroughdistributiongridinfrastructure,whetheradjustingoperationalsettingsofexistinggridequipment,ensuringnewgridinvestmentsarecarefullydesigned,orasalastresort,upgradingexistinggridequipmentbeforetheendofitseconomiclifetime.Technologyoptionsincludethefollowing.(a)Voltagecompensationequipment,includingtransformersettings.(b)On-loadtapchangingtransformerstoactivelymanagevoltageinrealtime.(c)Faultprotectionequipmentsettings.(d)IncaseswhereDPVaddsenoughvaluetojustifythecost,gridequipmentcanalsobeupgradedtoexpandthecapacityoftransformersandthethermallineratingofconductors.Largerconductorsyieldgreaterhostingcapacitythankstofewervoltageissuesandhigherthermallimits.(e)Theadjustmentorinstallationofharmonicfiltersandotherpowerqualitymanagementequipment.ThisisrelevantonlyforhighDPVpenetrationlevels.VoltagecontrolequipmentWhenDPVoutputsupplieslocaldemandforgridconsumers,itreducesordisplacesloadonthelocaldistributionfeeder,evenifnoneoftheDPVoutputisfedtothegrid.DPVproductionoccurringtowardtheendofaradialfeederline(asintroducedinChapter1),mayneedspecialmeasurestomaintainvoltagelevels32FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVBOX4Grid-FollowingandGrid-FormingInvertersInverterscanprovideadistributionsystemwithasuiteofflexibleservices.Theseincludefaultride-through,dynamicreactiveandactivepoweroutput,rampratecontrol,andanti-islandingprotection.Inverterscomeinseveralfundamentallydifferenttypes.Oneclassofinvertersaregrid-following,anotherclassaregridforming,andsomeinvertershavetheabilitytoswitchbetweengrid-followingandgridformingmodes.Aninverteringrid-followingmodeoperatesasacurrentsource(i.e.,alternatingcurrent).Inthismode,theinvertercanadjustoutputandphase-anglerelativetothebroaderdistributiongrid.However,thereferencevoltageandfrequencyregulationwilldependonanexternalvoltagesource(i.e.,thegridoradieselgenerator).Grid-followinginverterscanbeconnectedtoanintermittentDCcurrentsourcelikePVwithoutbatterystorage.Assuch,theinvertercaninjectavailablePVpowerintotheACnetwork,uptothelevelofPVoutputoruptothelevelofinvertercapacity,whicheverislesser.Ingeneraltoday,mostgrid-connectedDPVsystems’invertersoperateingrid-followingmode.Aninverteringrid-formingmodeoperatesasanACvoltagesourceandcontrolsthefrequencytoloadsservedbytheinverter.Grid-formingasafunctionappliestobothmaindistributiongridsandtolocalloadssuchasinmicrogridsoperatinginislandmode.Formostpowergridstoday,thegrid-formingfunctionisprovidedbylarge-scalerotatingsynchronousgeneratorsfromcentralpowerplantsconnectedtothetransmissionsystem.However,asinverter-basedgenerationgrowstolargersharesofapowersystem,inverterswillalsoneedtobegincontributinggrid-formingforthenetwork.Aninverterwithgrid-formingfunctionalityisrequiredforamicrogridtooperateinanislandmode,independentofthemaingridnetwork.Grid-forminginvertersrelyonbatterystorageoranotheractivepowersourcesuchasadieselbackupgeneratortoprovidepowernecessarytodynamicallyincreaseordecreaseoutputtobalanceloadsandmaintainlocalfrequencyandvoltage.Invertersthatareabletooperateinbothgrid-followingandgrid-formingmodesoftenhavetwoseparatesetsofACterminals.Thegrid-followingsetofterminalsisconnectedtoanACsourcelikegridpower.Thegrid-formingterminalsareconnectedtolocalloads(orasubsetoflocalloadsthatareidentifiedaspriorityloads).Whengridpowerisavailable,theinverteroperatesinagrid-followingmode,routingACgridpowerfromthegrid-followingterminalsthroughtheinvertertotheload.Inthismode,theinverterisoperatingasacurrentsourceand,ifthereisafeed-somearrangementwiththeutility,theinverterfeedsunconsumedDPVoutputintothegridviatheinverter’sgrid-followingterminals.Intheeventthatthegridgoesdown,theinverterswitchestogrid-formingmode,internallydisconnectingfromthegrid-followingterminalsandoperatingasavoltagesourcetosupplyconnectedloadswiththeinverter’sownACwaveform.Foranillustratedexample,seeFigureA2inAnnexA.Source:OriginalbasedonEtoandothers(2018),IEEE(2018),Linandothers(2020),Kroposki(2021),McAllisterandothers(2019),IRENA(2022).2:TECHNICALSOLUTIONSFORGRID-FRIENDLYDPV33withinanacceptablerange.ForDPVfedtothegrid,evenwhenDPVgenerationexceedslocaldemand,powercanbesteppeduptofeedthehighervoltagegridwithoutnecessarilyhavingtochangecables,aslongasthemagnitudeoftheflowdoesnotexceedthepeakloadforthatdistributiongrid(called“feederpeakcapacity”).Atornearthislimit,atransformerwithafixedturnsratiomightneedtobeexchangedforonewithvariabletapsettings(auto-tap)sothatthetransformercanaccommodatethedailycyclesfromadaytimeinjectedcurrenttonighttimeloadwithoutvoltagefallingoutofanacceptablerange.Installationofanon-loadtapchangeratthedistributiontransformerisacommonsolutiontomanagevoltageonfeederswithDPV.Theseallowdynamicadjustmentofvoltageatthetransformer.Alowersettingavoidssurgesonthecustomersideunderlow-loadconditionsorreversepowerflows.Ahighervoltagesettingensuresthattherearenounder-voltages,forexample,duringthenightandunderhighloads.Bydynamicallyadjustingtolow-load/highfeed-inorhigh-load/lowfeed-insituations,on-loadtapchangingtransformerscanmitigatevoltageissues.Whereothervoltagecompensationequipmentispresentinthedistributiongrid,itssettingscanalsobeadjustedtoaccountforDPV.ButvoltageregulatorsmayneedtoaccountforfluctuationsinDPVoutputcaused,forexample,bypassingclouds.Equipmentupgradesmaybeneeded.Voltagecontrolequipmentmayinclude:DPVunitscontrolledbysmartinverters;shuntandseriescapacitorbanks,staticVArcompensators(SVC),andstaticsynchronouscompensators(STATCOM).FaultprotectionequipmentLargecumulativecapacitiesofDPVrespondingtoabnormalgridconditionscanhavesystem-wideimpacts.Forexample,ifthereisafaultsomewhereinthenetwork,aDPVsystemmayshutitselfoff,andinsodoingitdoesn’tcontributefaultcurrentthatovercurrentprotectionreliesontodetectandisolatethefault.AnotherscenariomaybeifalotofDPVisprogrammedtodisconnectimmediatelywhengridACfrequencyisaboveorbelownominalvalues.LossofonegeneratorcouldtriggerallthePVtoshutdownimmediately,contributingtofurthercascadingoutages,asdiscussedfurtherbelow.Athighpenetrationlevels,reconfiguringorupgradingunderfrequencyload-sheddingrelayscanbecomeapriority.Substationsoftenuserelaysasalastlineofdefenseagainstthethreatofasystem-wideblackout.Thetraditionalrationaleforconfiguringsuchrelaysassumesthatdistributiongridsarealwaysloadsanddonotcontributetogenerationatthetransmissionlevel.Butiftherelaydisconnectsthesystemwhileitisfeedingpoweruptothetransmissionlevel,theproblemmaybeexacerbated.Existingrelaysmaythusneedtobereprogrammedorsetdifferentlyorreplacedbynewonesaltogether.Theseimpactscanalsobemitigatedbyconnectionstandards,suchastheIEEE1547-2018,thatspecifyfunctionsofDPVsysteminverterstocopewithabnormalgridconditions.ChangestoprotectionschemesmightalsoberequiredathighersharesofDPV,oncepowerflowstohighervoltagelevelsbecomecommon.Protectionschemespreventpowerflowduringfaultconditionsbyseparating(“sectionalizing”)problematiccircuitsegmentsfromthebroadersystem.Thefunctionoftheseschemesistodetectcurrentsurgesduringafaultandthentoisolatetheproblematiclinesectionuntilnormalconditionscanberestored.ModernprotectionschemescanoperatereliablyathighsharesofDPVbutmayrequireconfiguration.Gridoperatorswillrequiretrainingtoensurecorrectconfiguration.ConductorsandtransformersDPVdeploymentcouldatsomepointrequireupgradestolinesandtransformers.Thermalcapacitycanbecomerelevant,forexample,ifthereisalargeinstallationattheendofasmallerradialfeederline.Alarger-diameterconductor(orsimilarinterventionslikeanadditionalcircuit)maybeneededintheeventelectricityistobefedbacktothetransmissionlevelortoconsumersclosertothetransformer.34FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVEnhancingPowerSystemFlexibilityAtthepowersystemlevel,DPVsharesmanyactionareasandsolutionswithbulkPVandwindpowerplants.AsatypeofVRE,variabilityanduncertaintyofDPVoutputcallforsystemflexibility.Optionsincludethefollowing.(a)Improveoperationalforecastsforvariablerenewableresources.(b)Automatepowersystemoperationstorespondquicklyandefficientlytonetloadfluctuationandtoresourceforecasts.(c)Expandbalancingareasofgridssuchasbyincreasinginterconnections.(d)Dispatchotherpowerplantsmoreflexiblywithfrequentscheduleupdatesclosetorealtimeandatshortdispatchintervals.(e)Introducefast-actingreserveservicesand/orinstallsynchronouscondenserstocompensateforalackofsynchronousgenerationathighpenetrationlevelsofinverter-basedgeneration.System-wideDPVgenerationforecastsInmanypartsoftheworld,forecastsforsolarPVgenerationhavebecomeacommodity.IfcentralizedPVforecastsareavailable,thensystem-levelDPVforecastscanalsobeobtained.Calculatingsystem-wideDPVforecastsdepends,however,onaccuratedataonthelocationandsizeofDPVinstallations.System-wideforecastswillbemoreaccuratethemoredetailsareavailableabout,forexample,orientationandtilt.Fordetailedguidanceonusingforecastingsystemstoreducecostandimprovedispatchofvariablerenewableenergy,seeESMAP(2019).Centralized,system-wideforecastsshouldbeimplementedinanycase,integratingtheforecastsofdifferentproviders.Thisisespeciallyusefulincasesofhighuncertainty,asdifferentforecastmodelstendtodivergeundersuchconditions.Acentralizedforecastcomplementsplant-orportfolio-levelpredictions.ThelattermaybeusedforschedulingDPVgeneration.ButsubjectingDPVtostrictbalancingrequirementswouldbeconsequentialonlyforlargerinstallations.Smallrooftopsystemstendtoaggregateoutputandachievebalancingthroughthesystemoperator—likebalancingelectricitydemanditselfinmanysystems.Thatsaid,whereDPVispairedwithabatterysystem,morestringentschedulingrequirementsareadvisable.Thisisbecauseincentivesforgreaterself-consumptioncreatealesspredictableinterplaybetweenloadandDPV.Whileeachcanbeforecastaccuratelyinisolation,theirinterplayismorecomplexwhenlinkedviaastoragesystem.ESMAPoffersasimplifiedPVforecastingtooltoinformthedecisionsthatutilitiesmakeregardingbasicelectricitydispatch.ThisisillustratedinFigure8.Inonemode,thetoolprovidesadailysolarPVgenerationforecastwithhourlyresolutionforaPVsystemorportfolioofsystems.Real-timevisibilityandcontrollabilityVisibilityandcontrollabilityarefoundationaltopowersystemoperations,andtheyremainvalidathighsharesofDPV.Indeed,theybecomeevenmoreimportantasDPVsharesgrow,becauseaccurate,well-visualizeddataandreliablecontrolmayberequiredwhenmanymoreindividualassetsareinvolved.1515SeeIEA(2022c)forfurtherrecommendedpracticesonincreasingthevisibilityofadistributionsystemandconsumerdynamics.2:TECHNICALSOLUTIONSFORGRID-FRIENDLYDPV35FIGURE8:USERINTERFACE,ESMAP’SSIMPLIFIEDSOLARPVFORECASTINGTOOLSource:WorldBank(2021).Note:TheSolarPVForecastToolisafree,web-basedapplicationdevelopedandoperatedbythecompanyNnergixEnergyManagementSLonbehalfoftheWorldBank,utilizingNnergixknowledgeandweatherforecastspubliclyavailablefromtheUSNationalOceanicandAtmosphericAdministration(NOAA),withfundingprovidedbyESMAP.ButDPVinstallationsaredifferentfromlarge,centralplants.Forexample,connectingthemtoatransmission-levelSCADAsystemwouldbeunnecessaryandexpensive.Moreusefulwouldbealayeredapproach,differentiatedbyvisibilityandcontrollabilityrequirements.Thisapproachstartswithamechanism,andappropriateincentives,forregisteringDPVinstallationsalongsidebasicplantdata.Withsamplesfromreal-time,meteredgenerationsites,forecastingcancreateaccurategenerationdataandreliable,system-wideestimates.ThiswayofattainingvisibilityissufficientwhenDPVisnotthegrid’smajorelectricitysource.Utilitiescanimprovepowersystemoperationsbydeployingproductionmeterssystematicallyand,whereDPVpenetrationlevelsarehigh,byinstallingsmartmetersthatenhancevisibilityandallowawiderrangeofoperations.Also,utilitiescanaskconsumerswillingtoinstallDPVtoseektheirapprovalandinstallspecificcontrolhardware(e.g.,ripplecontrol).Itisgenerallyadvisable,however,toensurethatDPVsystemscanbereadilyadaptedtoperformmorecomplexfunctionalitieswhenandifthesemaybeneeded.Thefirststepinthisdirectionismonitoringwithsmartmetersandreal-timegeneration.Anotherstepwouldbetoadjustgeneration—whichcanrangefromasimpleon/offcommandtodiscretesteps,orevenadetailedsetpoint.Costandproportionalityshouldbeprimaryconcerns,togetherwithreliability.Forcontrolstrategiestoworkasdesigned(especiallyinactivecontrolcases)utilitieswillneedtelemetryandsensorstorenderpowerflowsvisibleinthedistributionnetwork.Thesevisibilityinstrumentsmayrequireinvestmentsinmethodstomonitorandmanagethemanydevicesusedattheendpointsofthelow-voltagenetwork.UtilitiesareexploringcentralizedmanagementsystemstomonitorandcontrolDPVassetsasinputsintosystemoperations(forexample,adistributedenergyresourcemanagementsystem,orDERMS)orincoordinationwithschedulingresponsibilitiesandoperatingequipmentandprotection36FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVsystems(e.g.,advanceddistributionmanagementsystem,ADMS;oractivenetworkmanagement,ANM).Thesesystemshelptodevelopacoordinatedandcollaborativedistribution,whereassetsparticipateonbothsidesoftheservicetransformer.InvestmentsinANMorADMSfocusontheentiredistributionsystem,utilizingtop-downstrategiestomonitorandcontrolmyriadassetsonlow-voltagesecondarynetworksaspartofalargerfleet.ThereissomedevolutiontosubsetsofDPVsystems,soincrementaladjustmentscanbemadeatthelocallevel.Giventhecapitalinvestmentsinthesesystems—notably,afullyintegratedADMS—utilitiesandsystemoperatorsareexaminingphasedrollouts,beginningwithDERMS.DPVandDERassetmanagementcouldthenbemergedwithsystem-outagemanagementorprotectionautomation(Hansonandothers2019).SystematizingSolutionsThischapterhashighlightedamenuofpotentialsolutionsforgrid-friendlyDPVatgrowinglevelsofpenetration,andhowDPVcancontributetoreliablesystemoperations.Achievingtheseoutcomes,however,dependsonhavingagridcode,whichisthefocusofChapter3,andgoodplanning,thetopicofChapter4.2:TECHNICALSOLUTIONSFORGRID-FRIENDLYDPV37IllustrativeanalysisofrooftopsinGrenada3:GRIDCODESFORGRID-FRIENDLYDPVLarge-scaledeploymentofgrid-friendlyDPVdependsonagridcode:thefullsetofoperationalandtechnicalrulesgoverningapowersystem.Connectionstandardsareanimportantpartofagridcode.ConnectionstandardsaretechnicalrequirementsthatDPVsystemsmustmeettobepermittedtoconnectandfeedsomeoralloftheiroutputtothegrid.ConnectionstandardsdonotnecessarilyapplytoDPVsystemsthatfeednoneoftheiroutputtothegrid.Feed-nonesystems(explainedinChapter1)mayneverthelessneedtocomplywithsafetyregulations,equipmentstandards,ormonitoringschemes.Althoughconnectionstandardsarejustonepartofthegridcode,bothtermsaresometimesusedinterchangeablyinliteratureonDER.ForDPVsystems,connectionstandardsestablishhowtheymustrespondtocertainpowergridconditions,suchasabnormalfrequencyandvoltageparameters,andunderwhichconditionstodisconnector“ridethrough,”remainingconnectedduringmildortemporaryabnormalconditionstohelpsupporttheoverallgrid.SuccessfuldeploymentofDPVdependsonstreamlinedconnectionstandardsthatlessentheadministrativeandanalyticalburdenforeachDPVplant.ForDPV,connectionstandardsmayrequireminimumresponsesundernormaloperatingconditionsandduringcontingencies,givingutilitiesastandardizedmeanstoenforceoperationalrequirements.SUGGESTEDGRIDCODEELEMENTSFORDPVGridcodescanhelpaddressawidesetofpotentialproblemsandsolutionsassociatedwithDPV,asintroducedinChapters1and2.ForgridcodestofullyaccountforDPVsystemissues,manyspecificelementscanbeconsidered.TheseelementsareitemizedinTableB.SomeelementsrelatetotheconnectionofDPVsystemstothegrid,whileothersconcernDPVcommunicationsandcontrol.Mostoftheelementsrelatetofunctionsoftheinverter,asdiscussedfurtherbelow.Countrieswithnogridcodeshoulddeveloponeassoonaspossible,whilecountrieswithagridcodemayneedtoupdateittoreflectexpectedfuturescenarios.Aninitialgridcodemaybedevelopedquicklybasedoninternationalexperiencetoensureminimumfunctionalityforsecureoperations(IRENA2022).However,itisimportanttostressthatgridcodesmustbeconsistentwiththespecificsofagivenpowersystem.Copyingvaluesfromadifferentsystemcanproduceinconsistentrulesthatareincompatiblewiththereliableoperationofthesystem.Nevertheless,animperfectgridcodeis,inmanycases,betterthannogridcodeatall,especiallywhenDPVorothertechnologiesarerapidlydeployed.AppropriategridcodeelementsforVRE,includingDPV,willvarydependingonhowsmallorlargeisthepowersystemandhowloworhighisthelevelofpenetration.Figure9providessuggestionsfromarecentstudybyIRENA.Successfulimplementationofgridcodescriticallydependsontheavailabilityofutilitystaffwithadequateskillsandtrainingaswellasschemestomonitorandenforcecompliance.Inmanycountries,maintenanceofpowersystemsisalreadyamajorchallengeevenbeforeconsideringtheincreasedcomplexityofdistributedresourceswithmorevaried,independentactors.Insuchcases,itisimportantforgridcodeauthoritiestothink39TABLEB:RELEVANTGRIDCODEITEMSFORDPVSYSTEMREQUIREMENTSGRIDCODEITEMDESCRIPTIONDPVCONNECTIONREQUIREMENTSClassificationofgeneratorCategorizesDPVorDERbysizetodefinegroupsandproviderequirementssizeperconnectionvoltageforeachcategory.Eachcategorywillvarycountrytocountryaccordingtolevelsizeofthesystemandthedifferentvoltagelevels.PleaseseeAnnex1foranexample.NormaloperatingSetspermissiblevoltagelevelstobedefinedforeachcategoryasvoltageconditions—voltagelevelrangeswoulddifferdependingontheconnectionpoint.Theoperationrangesaren’tdefinedinsomedistributiongridcodesforDPVorDERbutwouldneedtobedefinedtoavoidundesiredsituationsinthegrid.NormaloperatingSetspermissiblefrequencylevelsandrequirementstodisconnectafteraconditions—frequencycertaindurationoffrequencyaboveacertainrange.DPVmustalsoremainconnectedtothesystembelowadefinedrateofchangeoffrequencyanddisconnectaboveacertainrate.Theoperationrangesaren’tdefinedinsomedistributiongridcodesforDPVorDERbutwouldneedtobedefinedtoavoidundesiredsituationsinthegrid.Anti-islandingandEnsurethatallinvertershavecapabilitiestodetectoutagesandstopactiveintentionalislandingpowersupplytoprotectequipmentfromdamage.Bimodalinvertersmay,however,operateinstand-alonemodewhendisconnectedfromtheutility.BehaviorduringabnormalDefinesvoltageride-throughcapabilitiesdifferentlyfordifferentsizesofoperatingconditions—DPVwheretheyarerequiredtostayonline.Someutilitiesmaysetanvoltageride-throughadditionaloptionalrange.BehaviorduringabnormalDefinesthefrequencyride-throughrequirementsbythefrequencyrangeoperatingconditions—ofoperationwhereDPVorDERmustsustainoperationforadefinedfrequencyride-throughminimumtime.ProtectiontimesettingsDefineprotectiontimesettingsinthegridcode,permittingreasonabledelaysforover/undervoltageandover/underfrequencyeventsinlightofvoltageandfrequencyranges.ProtectionandfaultlevelsEnsurethattheprotectionsystemissettopreventfaultsandstaysconnectedinnoncriticalsituations,suchassmallvariationsinthesystem(bidirectional).ReconnectionafterfaultStatetheconditionsinthegridcodeunderwhichDPVmayreconnect(synchronizationtothegrid)(i.e.,voltageandfrequencylevelssustainedoveracertainperiod).Powerquality—rapidvoltageMaintainvoltagebelowapredefinedthresholdtopreventvoltagechangesfluctuationsduetoswitchingoperationsofDPVorDER.ReactivepowercapabilitiesMandatestheoperationofDPVorDERaboveacertainvoltagelevel(orsize)atanypowerfactorwithinthedefinedcapableoperationrangesagreedthroughthegridcode.Invertersneedtobesizedconsideringthecapabilitytoprovidevoltageregulation.DynamicvoltagesupportPrioritizesDPVorDERaboveacertainvoltagelevel(orsize)tosupplyreactivepowerforgridsupportduringabnormalconditions.ActivepowercontrolSetsasizethresholdforDPVorDERtobecapableofcontrollingthesuppliedactivepowerattheconnectionpointwhenrequested.Rampcontrol/spinningIdentifiesDPVorDERaboveacertainsizethatarerequiredtocontrolreservesoutputfluctuations(rampcontrol)orevenprovidefrequencycontrolreserves(spinningreserves)whenneededbythesystemoperator.FrequencyresponseRequiresDPVtoreduceactivepoweroutputaboveacertainfrequencythresholdaccordingtoadefinedfrequency—power-outputcurvedefinedbythegridcodeSyntheticinertiaRequireDPVorDERaboveacertainsizetoprovideinertialresponse.Powerquality—flickerComplywiththelimitsforDPVdefinedinthegridcodewhenenforced—morerelevanttowindpower.40FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVTABLEB:RELEVANTGRIDCODEITEMSFORDPVSYSTEMREQUIREMENTS(Continued)GRIDCODEITEMDESCRIPTIONHarmonicsHighlevelsofharmonicswilldamageequipment.DPVtocomplywithharmoniclimitsenforcedinthegridcodeatthepointofconnectionwherethelimitsvaryfromcountrytocountry.DPVCOMMUNICATIONANDCONTROLRemotecontrolbysystemSpecifysystemoperatorcontroloversystembalancingaboveacertainsizeoperatorofDPVorDER,toadjustlevelsofactivepoweroperationForecastingrequirementsRequireforecastingforDPVorDERaboveacertainsize(i.e.,DPVintheMWrange).Source:Originalbyauthorsforthisreport.throughtheriskandconsequencesofpotentialnon-compliancewithcertainprovision.Forexample,evenasmallnumberofDPVsystemscanposeasafetyrisktopowersystemtechniciansiftheydonotcomplywithanti-islanding(orintentionalislanding)requirementsduringagridoutage.Overtime,powersystemstudies(asdescribedinChapter4onplanning)canevaluatetheadequacyofexistingrequirementsandidentifypointstoimprovesothatgridcodesreflecttheneedsofthepowersystemtodayaswellasexpectedfuturedevelopmentscenarios.StandardsaroundtheworldarebeingrevisedtoincorporatenewcapabilitiesofferedfromDPVsystems(AEMO2019).NotablepastexamplesincludeGermany’sexpansionoffaultride-throughcapabilitiesin2012,andupdatesintheUnitedStatesledbyCaliforniaandHawaiiin2018(IEEE2018).THERATIONALEFORSPECIFYINGDPVINVERTERBEHAVIORINGRIDCODESInverterstandardsarekeyforhighsharesofDPVtocopewithandavoidsystemdisturbancesfromabulkpowersystem,asdiscussedinChapter2.Invertersettingsforgridinteractioncanandshouldbemandatedbygridcodeconnectionstandards.TheycandefinehowDPVinvertersinteractwithkeydistributionoperationalfunctions,includingtheregulationofvoltageandfrequency,themonitoringofpowerquality,andthefunctioningofprotectionsystemsneededforreliabilityandsafety(AznarandStout2018;IRENA2022).DPVthatadherestothegridcodeconnectionstandardscanbenefitpowersystems.EveningridswithlowDERpenetration,requiringadvancedinverterfunctionstodaycouldreducetheneedtochangesystemsinthefuture(IEA2022c).Forexample,itisgenerallynotpossibletoretrofitgrid-followinginverterstohavegrid-formingcapability.InitialapproachestoDPVconfigurationfollowedtheprinciplesbywhichdistributionsystemswereoriginallyplannedandoperated:“fitandforget”and“donoharm.”ExperienceincountrieswithrisingDPVshareshasshown,however,thatDPVintegrationrequiresamorenuancedapproach.Forexample,theGermangridcodeusedtomandatethatDPVinstallationsdisconnectfromthegridwhensystemACfrequencyreaches50.2hertz(Hz),orcyclespersecond.Thiswouldlead,thethinkingwas,toado-no-harmresponsetosurplusgeneration.Towardtheendof2020,however,GermanyhadaninstalledPVcapacityofapproximately70percentofpeakdemand,mostofwhichwasDPV,meaningthatdisconnectingallDPVat50.2Hzwouldhaveplungedthecountryintoasystem-wideblackout.Germanyhassincereviseditsgridcode,andeachDPVsystemnowdisconnectsatarandomlychosenvaluewithinfrequencyintervalsthatdeliverasmooth,system-stabilizingresponse(BDEW2016).3:GRIDCODESFORGRID-FRIENDLYDPV41FIGURE9:GRIDCODEFORMULATIONGUIDANCEBYGRIDSIZEANDLEVELOFVARIABLERENEWABLEPENETRATIONVREStoragefacilityGrid-forminginvertersGrid-formingservicesintegrationintegrationforstabilityissuesinandblack-startregionswithoutfunctionalitytobeHighFullfrequencyandhydropowerprovidedbynewassetsvoltagecontrolconnectedtocapabilitiesFrequencycontrolandhighvoltagelevelsactivepowercontrol(e.g.VREpowerplantsGrid-formingandperformancesuitableorlarge–scalestorage)black-startservicesforAGCintegrationfromstoragerequiredSteppingupLFSM-UandactivepowerFRTcapabilityandFRTcapabilityandactiveStartingcontrolperformanceactivepowercontrolpowercontrollabilitysuitableforAGCrequirementextendsrequiredforlow-voltageintegrationtonewlow-voltageconnectionsconnectionsRequirementsforNewrequirementsforenablingtechnologiesRequirementsforlargerfacilities(e.g.storage)enablingtechnologies(e.g.storage)RequirementsforAssetsmustwithstandenablingtechnologieswiderfrequencyand(e.g.storage)voltagerangeRequirementsmustalignwiththestateoftheart,NeedforcontrollabilitystandardsandrulesoftheVREindustryandFRTcapabilities(includingsmallDER)Powerquality,protection,suitablefrequencyoperatingranges,andLFSM-OmustapplytoallnewlyconnectedSmallSystemVREfacilitiesandenablingtechnologiesFormedium–voltageconnections,requirementsforpowerremotecontrolandFRTareneeded,butarenotyetcrucialforlow-voltageconnectionsMediumSystemLargeSystemSystemSizeSource:IRENA(2022).Note:AGC=automaticgenerationcontrol;DER=distributedenergyresources;FRT=faultridethrough;LFSM-O=limitedfrequencysensitivemodeforover-frequency;LFSM-U=limitedfrequencysensitivemodeforunderfrequency;VRE=variablerenewableenergy.42FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVThisexamplehighlightstwoimportantpoints:first,DPVcanbecomerelevantfortheoverallpowersystem,sotechnicalrulesmustkeeppacewithinstalledDPVcapacity.Second,suchrulesshouldbepragmaticandeasytoimplement,withfewrequirementsforcostlymonitoringandcontrolequipment.InregionswithhighDPVpenetration,inadequateresponsestosystem-widedisturbances(e.g.,theautomaticdisconnectionofDPVunits)riskworseningsystemconditionsratherthanimprovingthem.Toavoidthis,transmissionanddistributionplannersshouldcoordinatecloselytoinformandcomplywithappropriategridcodestospecifyandreflectthefunctionalcapabilitiesofDPV.Newfunctionalitiescanbetestedinpilotprograms.Autonomouscontrolsettings,forexample,canallowstakeholderstogainexperiencewithautomatedDPVmanagementofgridoperations.CaliforniaandHawaii(andelsewhereintheUnitedStates)havebegunincorporatingautonomouscontrolsettingsintoconnectionagreements,notablyforcircuitsnearingthelimitsofcapacity.Duringtheconnectionprocess,utilitiesandDPVuserscandevelopcustomsetpoint-basedcurvesthatautonomouslyadjustreactive,orreal,poweroutputbasedonterminalvoltagestolimittheneedforconventionalDPVintegrationmeasuressuchascurtailment(AEMO2019;Horowitzandothers2019;Palmintierandothers2016).Overtime,withgreaterinvestmentinmonitoringsystems,DPVcanexpandbeyondenergygenerationintoreliabilityandcapacitydistributionservicessuchasblack-startfunctionalitiesorprovidingfirmcapacity.DPVSYSTEMEQUIPMENTSTANDARDSANDCERTIFICATIONAREIMPORTANTFORENFORCEMENTOFGRIDCODESEquipmentstandardsdefinecapabilitiesandsometimesparametersofcomponentsinDPVsystemsforqualityperformance.InthecaseofDPVinverters,standardsprovideforthemanufacture,programming,andtestingofinverterstosafelyperformlistedfunctions,includingactivesupportfordistributionsystemoperations(EnergyTransitionInitiative2017).Attheconsumerlevel,dedicatedstandardsregulatethesafetyandinstallationofDPVsystemsonconsumerpremises.IntheUnitedStatesandLatinAmerica,theNationalElectricalCode(NEC)providesthebuildingcodetowhichallDPVsystemsmustbedesigned,built,installed,andusedforpowersystemsoperatedat60Hz.TheInternationalElectrotechnicalCommission(IEC)teststhesafetyrequirementsforDPVsystemsconnectingtopowersystemsbasedona50Hzoperation.Financers’evaluationsofDPVprojectsrelynotonlyonstandardsbutalsothecertificationofsystems,credibleinstallers,appropriateinsurance,andoperationsandmaintenancepackages(IFC2014).Certificationbodiesreviewdocumentstoverifythatequipmentcomplieswithstandards.Thecertificationprocessdependsonachainoftrust(Figure10).Aninternationallyrecognizedaccreditationbodymustalsoendorsethecertifiertoassuretheircompetenceandintegrity.TheInternationalOrganisationforStandardization(ISO)/IEC17065standardconcernsbodiescertifyingproducts,processes,andservices.ExamplesofcertifyingbodiesincludeAmericanNationalStandardsInstitute(ANSI),JointAccreditationSystemofAustraliaandNewZealand(JAS-ANZ),andDAkkS(DeutscheAkkreditierungsstelle[GermanAccreditationBody]).CertificationofDPVequipmentcanbetime-consumingandexpensive,butisimportanttoassuretheintegrityofthesystembyrequiringthatallcomponentsareadequate.Countriesthathaveinsufficientresourcestocertifyequipmentdomestically,maybepromptedtoborrowaninternationalcertificationfromelsewhere.Tobevalid,followinganinternationalcertificationgrantedinanotherlocationrequiresagridcodesimilartotheoneinusewherethecertificationwasgranted.3:GRIDCODESFORGRID-FRIENDLYDPV43FIGURE10:CERTIFICATIONANDTHE“CHAINOFTRUST”FORDPVEQUIPMENTGovernmente.g.ISO/IEC17065InternationalRecognitione.g.IEC61215standardsAccreditationbodyAccreditationorganizationCertificationbodyCertificationCertificateSource:Originalfigurepreparedbytheauthorsforthisreport.PROCEDURESFORDPVCONNECTIONSHOULDBESIMPLEANDPRAGMATICConnectionagreements(alsoknownasinterconnectionagreements)providethetechnicalandregulatorybasisforDPVsystemstobeconnectedtothegrid.Connectionstandardsareestablishedbyregionalbodiesworldwide:theInstituteofElectricalandElectronicsEngineers’IEEE1547(NorthAmericaandinternationally),TechnicalStandardsforConnectivitytotheGrid(India),EN50438:2013(Europe-widetechnicalspecification),VDE-AR-N4100(Germany),andAS/NZ4777(AustraliaandNewZealand).Aconnectionprocessgenerallyinvolvesthefollowingsteps.1)Application.Aservicecompanyorconsumerappliestotherelevantauthority(e.g.,distributioncompanyorutility)toinstallaDPVsystemataspecificlocationinthedistributiongrid.Theapplicantsubmitsdocumentsdetailingsystemcapacity,feedarrangement,inverterspecifications,andotherspecificsofthedesign.Theapplicantmightrelyonknownstandardsorconsulttheauthorityorotherexpertsonhowtomeetrequirementsindesigningandprocuringequipmentforthesystem.2)Review.Therelevantauthorityreviewstheapplicationagainsttechnicalstandardsandgridcoderequirements,includingforbasicsafetyandreliabilityandknownhostingcapacityofthelocaldistributionnetwork,todetermineiftheapplicationcompliesassubmittedorrequiresmodificationstobecomecompliant.ConnectionagreementscanbestreamlinedtoapprovesystemsdesignedtokeepwithinspecificparameterssuchasacapacitythresholdforsmallerDPVsystemsandwhereamplehostingcapacityofthelocaldistributionnetworkexists.Thiscanavoidtheneedforaspecificstudytoensurethesystemisgrid-friendly.However,technicalscreensmaymischaracterizepotentialimpactsespeciallyinaggregate(Box5).Detailedassessments,ontheotherhand,canbetime-consumingandcostly,butmaybenecessaryandbeneficialforlargeorcomplexprojectstooptimizedesignsincludingtopotentiallyprovidegridservices.44FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPV3)Issuance.Theauthorityissuestheconnectionagreement,authorizingtheprojectdevelopertoproceedwithinstallationandconnectionofthesystemasspecified.TheagreementtypicallyalsodocumentsthepermissibleoperationalbehavioroftheDPVsystem.4)Connection.ThedeveloperinstallstheprojectsandtheprocessiscompletewhenaDPVplantstartsoperation(commissioning).Auditsmaybecarriedouttoensurecompliance.AtlowDPVpenetrations(regardlessofconfiguration),utilities,distributioncompanies,regulators,DPVusers,anddevelopershavesomediscretionoverdesignandcriteriaintheconnectionreview.Thisflexibilitycanbeusedtobalancetechnicalrigorwithaforward-lookingperspectivefocusedonsystemintegration.Aspenetrationgrows,stakeholdersshouldreviewandupdateconnectionproceduressoprocessesbalancedeploymentwiththetechnicalrequirementsofdistribution.Box5discussesprosandconsoftechnicalscreeningcriteria.BOX5TechnicalScreeningCriteria:HelpfulorNot?SomecountriesusetechnicalscreensduringDPVconnectionreviewstodeterminethepotentialsafetyandreliabilityimpactsofaproposedinstallation.Technicalscreensfast-trackthereviewofinnocuoussystems(i.e.,thoseunlikelytoinduceimpacts),consideringthatutilityreviewscanoftenbethemosttime-consumingpartoftheconnectionprocessandmostDPVconnectionrequestsareinsignificant.Theygenerallyfocuson(1)theriskofunintentionalelectricalislands(i.e.,distributedgenerationunsafelyfeedingthegridduringasystemoutage);and(2)theimpactsonvoltagecontrolprograms.TechnicalscreenscommonlyrelyonhostingcapacitycalculationstoestimatethepointwhereDPVwouldinducetechnicalimpactsonsystemoperations.Suchscreeningcriteriaarewidelyused,forexample,inIndiaandtheUnitedStates.InIndia,forexample,regulationsformanystatesspecifythatDPVinstallationsizewillbelimitedtoagivenpercentage(e.g.,80percent)ofthecustomer’speakload.AuthoritiesinGermanyandAustraliaimposenogenerallimitsonfeederpenetration.TechnicalscreensandhostingcapacitythresholdsoftenunderstatethecapabilityofDPVsystemstoavoidunintentionalislandingthroughpreprogrammedclearingtimesortheavailabilityofcontrolmodestolimitvoltageimpacts.Toimprovetheuse,ifany,oftechnicalscreeningcriteria,utilitiesandsystemoperatorscanconsidermetricsrelevanttotheimpactsofDPVonlow-voltagedistributiongrids,suchasDPVcapacitypenetrationrelativetominimumfeederdaytimeload.Source:BasedonAznarandStout(2018);EnergyTransitionInitiative(2017);Horowitzandothers(2019);Palmintierandothers(2016);Rylanderandothers(2015);Singhandothers(2019).3:GRIDCODESFORGRID-FRIENDLYDPV45Analysisofrooftopsinİzmir,Türkiye4:APPROACHESTOPOWERSYSTEMPLANNINGWITHDPVThischapterdescribesvariouspossibleapproachestopowersystemplanningwithDPV,andkeyissuestoconsiderinchoosinganapproach.DPVcanberelevantforpowersystemplansatdifferentlevels:distribution;bulkgeneration;andeventransmission,dependingonthelevelofDPVandothervariablerenewablesinthesystem.Whererelevant,powersystemplanningcanalsotakeDPVintoaccountindifferentways.Nosingleapproachwillsuitallcountries,justaspowersystemplanningitselfvariesfromcountrytocountry.Untilrecently,mostcountriesaroundtheworldhavetakenarudimentaryapproachtoDPVinpowersystemplans.UtilitieshavehistoricallyrespondedtoDPV-relatedchangesonthegridinamannerthatisreactiveandadhoc,ratherthanproactiveorstrategic.RapidDPVgrowthhasrevealedtheneedforplanningtoevolve.ManyregionswithhighDPVpenetrationratesareupdatingtheirmethodologiesforpowersystemplanningtobetterreflectthecharacteristicsofDPVandtoimproveoverallhostingcapacities.Moreadvancedapproachesareemerging.Whilenewapproachesarenotyetwellestablished,therearesomegeneralsteps,principles,andcommontoolstoconsider.Thesearethefocusofthischapter.TRADITIONALPOWERSYSTEMPLANNINGAPPROACHESVARYBYCOUNTRYANDAREEVOLVINGEvenbeforeconsideringDPV,itisimportanttorecognizehowgeneralapproachestopowersystemplanningcanvarysignificantlyacrossdifferentcountries.Ingeneral,powersystemplanninginvolvesprojectingfuturedemandforelectricity,andidentifyinginvestmentsneededforgenerationandgridinfrastructuretoeconomicallymeetthisdemand,takingintoaccountkeyconstraintsandassumptions.Thesemaybetechnical,suchasreliabilityandsafety,orpolicyrelated,suchasenvironmentalstandardsandtargetyearsforelectrificationandemissionsreduction.Powersystemplanningcaninvolvevariousdataandanalysistools,modelsandprocesses,toaddressdifferentspecificquestions(Boyd2016).Traditionally,themainmodelinpowersystemplanningiscapacityexpansion.Capacityexpansionmodelssimulatebulkgenerationandtransmissioncapacityinvestmentstoidentifytheleast-costmixofpowerplantsthatshouldbebuilttomeetdemandincomingyearsanddecades(e.g.,5to30years).Typically,thesemodelsuseasampleofrepresentativedaysforeachyearforsimplicity(ratherthansimulateall8,760hoursofayear).Acapacityexpansionmodelmaybesupplementedbyothermodelssuchas:•Productioncostmodel,alsoknownasunitcommitmentandeconomicdispatch.Thistypicallytakestheoutputsofacapacityexpansionmodelandsimulatethepowersystem’soperationathighertemporalresolution(hoursto5-minuteintervals)forallhoursofrelativelyshorttimeperiods(e.g.,oneweektooneyear)toidentifyleast-costdispatchofbulkpowerplants.47•Networkreliabilitymodel.Thesesimulatetransmissionnetworkoperationsoververyshorttimeperiods(e.g.,30secondsto1minute)toassessgridadequacyundernormaloperationconditionsandcontingencies(steadystateswithallormostassetsavailable)anddynamiceventssuchasfaultconditions.Outputsofaproductioncostmodelmayserveasinputstonetworkreliabilitymodelandviceversa.•Electrificationplanning.Incountrieswherethepopulationlacksuniversalaccesstoaccess,aleast-costgeospatialelectrificationplanmayidentifywhichcommunitiestoprioritizeforgriddensificationandextension,andwhichmaybemorecost-effectivelyservedbynon-gridelectricitysolutionssuchascommunityminigridsorstandalonehouseholdPVandbatterysystems.16Planningpracticesvaryfromcountrytocountryinimportantways.Variationsinclude:theextenttowhichgeneration,transmission,anddistributionareplannedtogetherorseparately;timehorizon,geographiccoverage,andtemporalandspatialresolutions;thesophisticationofdataandmethodsofanalysisthatinformtheplans;therolesandinvolvementofdifferentstakeholders;thedegreetowhichplansarefollowedinpracticetoguideactualinvestments;andhowfrequentlyplansareupdated.Theparticularapproachpursuedinagivencountrycontextdependsoftheavailabilityofdata,technology,expertise,andfunding.Regulationandinstitutionsarealsoimportant.Somelow-incomecountrieslackanyformalpowersystemplansduetoresourceconstraintsandlimitedinstitutionalcapacity.Whileallmodelsrequireexpertstomanageinputs,runthemodel,andinterprettheoutputs,someadvancedmethodsforpowersystemplanningrequiresophisticatedcomputationalresourcesforprobabilisticanalysis.Historically,planninghasinvolveddiscretetracksforgeneration,transmission,anddistribution.Forsmallpowersystemswithoutatransmissionnetwork,generationanddistributionareoftenplannedseparatelyeventhoughtheyarecloselylinked.Withinthistraditionalapproach,integrationacrossplanningtracksmaynotbeseenasimportant,giventheassumptionsthatpowerflowsinonedirectionandthatdemandisinflexible.Globally,thedevelopmenttrendistowardmoreintegratedplanning.Forlargepowersystems,moreintegratedapproachesgenerallyrequirehigherlevelsofresources,andgreatercoordinationamongstakeholders.Suchanapproachisalreadyevidentinmiddle-incomecountries(e.g.,LatinAmerica).Incountrieswithmanyseparate(horizontallyunbundled)distributioncompanies,technologiessuchasadvancedmetersandSCADAcanhelpfacilitatecommonapproachestocoordinatewithplanningbulkgenerationandtransmission.Akeyelementoftheplanningprocessistoanalyzethecurrentdemandforelectricityandprojectfuturedemandbasedonpopulationgrowth,economicactivity,andotherfactors.Traditionally,demandisexogenoustopowersystemmodels,andisassumedtofollowpredictabledailyloadcurvesthataremodulatedbyweekdayandperhapsseason.So,thecapacityoftheentirepowersystem—frombulkgenerationstationstothegrid—isbuiltouttomeetpeakdemandacrossallenduses.17InmanyLMICs,distributionplanningtypicallyinvolvesconstructingorupgradingsubstationsandfeederstomeetfuturedemandandaccesstargetsatleastcost(GeorgilakisandHatziargyriou2015).Thisprocesstends16Foranexampleofthisapproach,forMyanmar,seeWorldBank(2016).17Thisistrueforcapacity-constrainedpowersystems—thatis,thelimitingfactorisgenerationcapacitywhilefuelitselfisgenerallyalwaysavailable(fossil-andnuclear-dominatedsystems).Bycontrast,systemswithalargeshareofhydrogenerationcanalsobeenergy-constrained:demandcanbemetatanygivenmoment,buttotalproductionmaynotbeablemeetalldemandoveralongerperiod.48FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVtooverlookDER.Somedemand-sideflexibilitymaybeachievedthrough,forexample,contractswithindustrialconsumerstoshiftproductionduringsystempeaksorextremeeventslikestormsorprolongedcoldspells.PowersystemplansinLMICsaretypicallyupdatedevery5–10yearsorevenlongerinsomecases.Mosthigh-incomecountries,forcomparison,updateplansmorefrequently,suchasevery3–5years.Periodicreviewandupdatingofplansisimportanttooptimizetheuseofavailableresourcesandaccountforemergingissues.Theintegrationofrenewableenergysourcesandpursuitofdecarbonizationarealsopromptingpowersystemplanstobeupdatedmorefrequentlythaninthepast.Vietnam,forexample,wasrecentlyrecommendedtousepowersystemplanningasadynamicinvestmentdecisiontoolthroughacontinuousprocessthatperiodically,perhapsevenannually,examinesthechangesinmarketconditions—demand,costs,technologicalprogress—whileincreasinglyfactoringin(currentlyuncaptured)localandglobalexternalities.Suchanapproachcanavoidapotentiallong-termcarbonlock-inthatisnotalignedwithpolicygoalswhilealsoshieldingtheeconomyfromimportrelianceonandpricevolatilityoffossilfuels(WBG2022).POWERSYSTEMPLANNINGCANADDRESSDPVINAVARIETYOFWAYSWheretraditionalpowersystemplanninghasseriouslimitationsforDPV,avarietyofalternativeapproachesarepossible.Theseincludethefollowingthreearchetypes.1.AdjusttraditionalpowersystemmodelstoaccountforDPV.PlannersneednotwaitforentirelynewmodelstostartaccountingforDPV.Mosttraditionalmodelscanincorporatevariablerenewablesanddistributedresources,includingDPV,toadegree.However,legacymodelsmaynotcaptureenoughdetailtoreflectimportantchallengesandopportunitiesthatemergeasrenewablesanddistributedresourcesbecomemoreprevalent.2.Conductdiscreteintegrationstudiesspecificallyforvariablerenewablesand/ordistributedresources,supplementarytoconventionalpowersystemplans.DiscretestudiesmaytakeconventionalplansasaninputthenmodelthebehaviorofDPVinthatcontexttoassessimpactsonpowersystemreliability,stability,andcost.Thisistypicallybeyondthescopeofconventionalgridadequacyassessmentforcountrieswhereallgenerationisdispatchable.Thetimehorizonforanalysisindiscreteintegrationstudiescanvarysignificantly.Neworupdatedstudiesmaybeneededeachtimesignificantnewinvestmentsorchangestothepowersystemareexpected.3.Dointegratedplanning.Anintegratedapproachaimstoexplicitlyconsidertheinterdependenceofdifferentcomponentsofthepowersystemandtheimpactofdifferenttypesofgenerationanddemandoneachother.Theroleofvariablerenewablesanddistributedresourcestohelpmeetelectricitydemandcanbeanalyzedindetailaspartofpowersystemplanningfromtheoutset.Linkinganditeratinganalysescanco-optimizepowersystemcomponentsthatwouldotherwisebeplannedindependently.Integratedplanningthusrepresentsanevolutionbeyondtraditionalapproaches.Theabovethreearchetypalapproachesarenotexclusive.Aspectrumofvariationsarepossiblebetweentraditionalandfullyintegratedapproachesateitherextreme.Furthermore,evenanintegratedplanmaystillrequiresupplementarydiscretestudies.Capturingthecomplexityanddiversitywithindistributionsystemscanbedifficulttogeneralizeacrossanentiresystem.Therefore,plannersmaysupplementoriteratesystem-wide4:APPROACHESTOPOWERSYSTEMPLANNINGWITHDPV49BOX6AssessingIntegrationofRenewablesforThailand’sPowerSystemThailand’s2015PowerDevelopmentPlanprovidedpowerdemandforecastsandagenerationandtransmissioncapacityexpansionplanto2036.In2018,thisplanwasusedasthebasisforaproductioncostmodelthatsimulatedvariousscenariosofvariablerenewabledeploymentthroughto2036.Themodelanalyzedandcomparedtheoperationalandeconomicimpactsofdifferentlevelsofvariablerenewablesinthepowersystem,aswellastheefficacyofdifferentflexibilityoptions.TheanalysisfoundthatThailand’spowersystem,asplannedforin2036viathe2015plan,wouldbetechnicallycapableofaccommodatingsubstantiallyhighersharesofvariablerenewables.Italsofoundthatmeasurestoimprovesupply-sideanddemand-sideflexibilitycouldreduceoperatingcostsinareliablemanner.Source:IEA(2018).planswithanalysesspecifictorepresentativesitesforkeyprojects.Eachsuccessiveplanorstudycanbuildonthefindingsofpastanalysesandonexperiencegainedinimplementation.SimplyadjustingtraditionalmodelsmaysufficeincontextswhereforecastsshowonlylowlevelsofDPVdeployment,orwhereDPVisexpectedtoservemostlyasabackup(i.e.,feed-nonearrangements).Thismaybethecaseforpowersystemssufferingfromfrequentorsevereoutagesandthathavelowprospectsofimprovingovertheplanningperiod.DPVdeploymentcanstillbeassessedfeederbyfeederasneedsarise.Eveninsuchcases,utilitiesinaviciouscycleofchronicunderperformancecanplanbottom-uptousegrid-connectedmicrogridswithDPVasa“bootstrap”toimproveservicereliability,andincreasebillcollections.18ForpowersystemswithhighforecastratesofDPVdeployment,goodpracticeistoundertakeintegratedplanningorelseanintegrationstudy.ThisincludesforcountrieswhereDPVisasourceofleast-costgeneration,suchasinsmallorland-constrainedcountries.Insuchcontexts,simplyadjustingtraditionalpowersystemmodelsmaynotsuffice.Integratedplanningandintegrationstudiescanhelptoensurethatthepowersystemismorereliableandresilientwhilealsominimizingcostsandenvironmentalimpacts.TheycanidentifywaystoenhancehostingcapacitiestomatchtheforecastgrowthlevelortomaximizeDPVasaleast-costgenerationsourceandavoidoverinvestmentinbulkgenerationorgridupgradesthatmaybelessefficient.ExpertsconvenedbytheIEAhaverecommendedadetailedsetofpracticesforrenewableintegrationstudies,includingspecificallyforPV.19Keyfindingsfromthisworkarereflectedbelow.IntheUnitedStates,theWesternWindandSolarIntegrationStudyfrom2010to2015brokegroundtodemonstratehowexistingpowersystemplanscanaccommodatelargersharesofvariablerenewables(NREL2015).Box6providesamorerecentexamplefromThailand.18“Bootstrap”heremeansusinginitialminimalresourcestoliftoneselfupoutofabadsituation.ThisandotherDPVusecasesaredetailedinESMAP(2021),DistributedPVinEnergySectorStrategies,thefirstreportinthepresentseries.19SeeHolttinen(2018),andrelatedresourcesoftheIEA(2023)PhotovoltaicPowerSystemsProgramme(PVPS)athttps://iea-pvps.org/50FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVGENERALSTEPSANDPRINCIPLESFORPOWERSYSTEMPLANNINGWITHDPVTheremainderofthischapterdescribesasetofstepsgenerallyapplicableforpowersystemplanningwithDPV(Figure11).20Somestepswilldifferinthedetailofhowtheywouldapplyinatraditionalmodelversusadiscreteintegrationstudyorintegratedplanningapproach.However,sincethosethreearchetypalapproachescanbecombinedorvaried,thedistinctionbetweenthemcanbeblurry.Asaresult,thefocushereisonwhatstepsapplytoanyorallapproachesingeneral,whilenotingspecificissuesthatmayapplytoacertainapproach.Thestepspresentedincludeconsiderationsrelevantfordistributionlevelplanning,aswellasconsiderationsforthebroaderpowersystem,includingtransmission.Distributionplanningmayoccuraspartofintegratedpowerplanning,orasastandaloneexercisebasedonexistingpowersystemplans.Inaverticallyunbundledpowersector,anintegrationstudywithDPVwouldtypicallybetheresponsibilityofdistributionutilitiesordistributionsystemoperators.Inlargepowersystemswithahighorrapidlyrisingshareofdistributedresources,coordinationbetweentransmissionanddistributionsystemoperatorsisimportantforthegridtoobtainthefullvaluefromservicespotentiallyprovidedbyDPV.FIGURE11:GENERALSTEPSRELEVANTFORDIFFERENTAPPROACHESTOPLANNING2.Setobjectives3.Selectmethods10.Monitor1.Engage4.Collateandevaluatestakeholdersdatainputsoutcomes5.Devise9.Implementscenariosplan/s8.Makeandissueplan/s7.Iterate6.SimulateandandoptimizeassessSource:Originalfigurepreparedbytheauthorsforthisreport.Note:Thesestepscanbeappliedgenerallytotraditionalorintegratedpowersystemplanningortoasupplementarydiscreteintegrationstudyforvariablerenewablesand/ordistributedenergyresources.Thestepsmaynotbestrictlysequentialordiscrete.Stakeholderengagementcanoccurthroughouttheentireprocess.20ThissectiondrawsonStanfieldandothers(2021),Ismaelandothers(2019),Holttinen(2018),StanfieldandSafdi(2017),andLindlandothers(2013).4:APPROACHESTOPOWERSYSTEMPLANNINGWITHDPV51Stepsmaybealteredandsimplifiedorelaboratedtosuitlocalcircumstancesandneeds.Inallcases,thescopeanddetailofapproachshouldaccountforinstitutionalresourceconstraintsandopportunities:data,technology,expertise,potentialcollaborationwithregionalpartners;internalfunding;andavailabilityoftechnicalandfinancialsupportfromdevelopmentpartners.UtilitiesinsomeLMICslackadvancedtoolsandmethodologiestoplanexpansionofDPV.Planningdonewithexternalsupportshouldconsideropportunitiestocultivateexpertiseandbuildinstitutionalcapacityamonglocalpersonneltoatleasthelpdesignandinterpretmodellingresults.Thismayrequireinvestmentsingeographicinformationsystems(GIS),modelingsoftwarelicenses,dataacquisition,andtechnicaltrainingsuchasoninvertercapabilitiesandhostingcapacityanalysistechniques.Ifdataareunavailabletosupportachosenanalyticscope,methodsandplansmayneedtobesimplified.Step1:EngagestakeholdersFromtheoutsetitisimportanttoconsiderwhichstakeholdersarerelevantfortheplanningprocess,andengagethemstrategicallythroughout.Earlyandconsistentengagementcanhelptobuildandmaintainconsensusoncriticaldecisionstobemadeinsubsequentstepsandtoparticipateinmonitoringandevaluation.Principlesforgoodpracticeincludeopenmembership,openaccess,neutralfacilitationandreporting,andactiveinvolvementofutilities.StakeholderstoconsiderspecificallyforDPVinclude:distributionutilities,electricityretailers,consumerrepresentatives,projectdevelopers,andenergyservicecompanies.Step2:SetobjectiveThefirstcriticaldecisiontomakeisestablishingtheobjectiveofaplanningexerciseandspecificquestionstobeanswered.Forexample,thefocusofplanningmaybeonminimizingcostofserviceforatargetlevelofDPVdeployment,oronidentifyinghowmuchDPVcanbedeployedwithinafixedcostofservice.Indecidingtheobjectiveofplanning,considerrelevantpolicies,strategy,codesandstandards.ConsidertherangeofpotentialusescasesforDERandDPVfeedarrangements(seeBox1onpage15,andAnnexA).Afocusononeorotherusecasesmayhaveabearingontheoverallobjectiveofplanning.ExploringthepotentialapplicationofDPVasaT&DalternativeandforancillaryservicesmayrequiredifferentanalysisthanforuseofDPVforleast-costgeneration.Forexample,wheredisplacedgenerationfromDPVmightbesignificant,plannersneedtoconsiderflexiblegenerationoptions—thatis,dispatchablegenerationthatwouldfulfillthebalancingneedsofthesystem.ForcasesofDPVasleast-costgenerationandT&Dalternative,coordinationbetweenplanningentitiesiskeytoensurethatDPVresourcesarereflectedinbothgenerationandtransmissionplanning.Moreover,coordinatedmanagementofDPV,suchasVPPs,canhelplimittheneedfordispatchablegeneration(seeBox3onpage28).Step3:SelectmethodsOncetheplanningobjectivehasbeendecided,thenselectthemodelsortoolforanalysistosuit.Itisimportantforthechoiceoftoolstobeguidedbytheobjectiveratherthantheotherwayaround,sincedifferenttoolsprovidedifferentinformation.Thechoiceofmethodisacriticaldecisionbecauseitisshapedbythekindandqualityofdataavailableinthegivencountry(Step4).Insomecases,availabledatamayconstrainthemethod.Inothercases,thechoiceofmethodmaypromptcollectionofnewdata.Keyquestionsformethodinclude:whattypesofgridimpactstostudy;howtoprojectDPVdeployment;andhowtoreflectDPVinstudies.52FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVWhattypesofgridimpactstostudy?Parametersofscopetoconsiderforpowersystemanalysisincludewhichenergysectorcomponentstofocuson(e.g.,gridelectricityonlyoralsospaceheating,waterheating,etc.)andthetimehorizon,geographicarea,andspatialresolution.Figure12showspotentialissuestostudyfortheimpactofvariablerenewablesatthedistributionlevelandatthetransmissionorpowersystemlevel,differentiatedbytimescaleandrelevantgeographicalarea.Notallplanningprocessesneedtolookatallaspectspresentedhere.Analysescanbedoneinphases.Forexample,afirstphaseforlowersharesofvariablerenewablesmaylookatshort-termimpactsoncurrentpowerplantsinproductioncostsimulations,oronlocaldistributionnetworks.Subsequentstudiesforhighersharesoverthelongertermmaylookatnetworkadequacyandcongestion,aswellasgenerationcapacityadequacy,includingthecapacityvalueofDPV.Considerthechoiceofmethodforhostingcapacityanalysis.Threearchetypalmethodsarestreamlined,iterative,orstochastic(StanfieldandSafdi2017,Stanfieldandothers2021):FIGURE12:POTENTIALIMPACTSOFVARIABLERENEWABLESONGRIDSATDIFFERENTTIMESCALESANDSPATIALAREASFORSTUDIESArearelevantforimpactstudiesTransmissionsystemstudiesSystemwideFastfrequencyManuallyReducedAdequacy1,000–5,000kmresponseactivatedemissionsofpowerfreq.reserveRegionalGridHydro/thermalAdequacy100–1,000kmstabilityTransmissionefficiencyofgridefficiencyLocalVoltageCongestion10–50kmmanagementmanagementPowerDistributionqualityefficiencyDistributionsystemstudiesMicrosecondsSecondsMinutesHoursDaysYearsDecadesTimescalerelevantforimpactstudiesSource:BasedonHolttinen(2018).Note:Theyellowareaanddarkbluebubblesindicateissuesofregionalscaleatthetransmissionandpowersystemlevel.Thelightorangebubbleareissuesrelevantformorelocal,distributionsystemstudies.Transmissionanddistributionefficiencyreferstogridlosses.Hydro/thermalefficiencyreferstolossesingeneration.“Freq.reserve”isfrequencyreserve.km=kilometer.4:APPROACHESTOPOWERSYSTEMPLANNINGWITHDPV53•AstreamlinedmethodappliesasetofsimplifiedalgorithmsforeachpowersystemlimitationtoapproximatetheDERcapacitylimitatnodesacrossthedistributioncircuit.•Aniterativemethod(alsosometimesknownasthedetailedmethod)directlymodelsDERsonthedistributiongridtoidentifyhostingcapacitylimitations.Apowerflowsimulationisruniterativelyateachnodeonthedistributionsystemuntilaviolationofapowersystemlimitationisidentified.•Astochasticmethodstartswithamodeloftheexistingdistributionsystem,thenaddsnewDPV(orotherDER)ofvaryingsizestoafeederatrandomlyselectedlocations.Thefeederisthenevaluatedforanyadverseeffectsthatarisefromthisrandomallocation,toderiveahostingcapacityrange.IssuesrelevantforassessingDPVhostingcapacitymayinclude,asshowninFigure12:voltagemanagement,distributionefficiency,congestionmanagement,powerquality,gridstability,andgridadequacy.Considerdetailslikeminimumnumberandtypeofloadhourstobeanalyzed.Probabilisticanalyses,orelsemultiplescenarios,helpmakedistributionplanningrobusttofutureuncertainties.PowerflowdynamicsisaspecificareatostudytoidentifynodeswhereDPVcaneaseexistingcongestionandwhereDPVfeedinriskscontributingtocongestion.PlannersneedtoaccountforpowerflowdynamicsunderawiderangeofoperatingconditionstoensurethatthepowersystemcanoperatereliablyandefficientlywithDPV.PlannersneedtoconsidertheaggregateimpactsofDPVonpowerflowdynamicsindeterminingtheplacementandsizingofgeneration,transmission,anddistributioninfrastructure,aswellasthedevelopmentofcontrolandprotectionschemes,accountingforregion-specificcharacteristics.HowtoprojectDPVdeployment?AllplanningapproacheswithDPVrequireprojectionsofaggregateDPVoutput.Thetemporalandspatialresolutionandaccuracyoftheseestimatescanvarygreatly.ProjectionsentailassumptionsaboutthesizeandnumberoffutureDPVsystems.Ideally,thelocationsofDPVsystemsshouldalsobetakenintoaccount.SolarprofilesappropriateforDPVsystemscanthenbeappliedtoprojectoutputforthehoursofrepresentativedaysofayear.ProjectingDPVdeploymentismorechallengingcomparedwithloadforecasts(awell-knownexerciseforutilities).However,accurateDPVdeploymentprojectionsareimportantasinaccurateprojectionscanresultinhighcostsforutilityinvestmentsthatcouldotherwisebeavoided.Under-estimatingDPVdeploymentcanleadtoneedlesscapitalexpendituresonutility-scalegenerationandunderinvestmentinflexibilityoptions,threateningthereliabilityofthegrid.Over-estimatingDPVdeploymentcouldleadtheutilitytofillgenerationshortfallswithenergyfromcostlysourcessuchasemergencyrentalgenerators.WhiletheexactnetloadshapedependsonthedemandstructureandtheaggregatePVgenerationprofile,increasedrampingrequirementsforotherpowerplantsduringthemorningandeveninghoursaretypicalforsystemswithlargerPVcontributions.DPVdeploymentestimatescancompriseseveralinterrelatedanalyses.•Typically,utilitiesorplannersfirstassessthemaximumpossibleDPVdeploymentgivenanytechnicallimitations,suchasavailableroofspace,orientation,andshadingatrequireddetailedgeospatialresolutions.Box7showcasestechniquestomapthistechnicalpotentialofDPV.•Followingfromthis,theeconomicpotentialcanbedetermined—i.e.,themaximumamountofviableDPVdeploymentaccordingtoeconomiccriteria(suchasnetpresentvalue).•Then,futureDPVdeploymentcanbeestimatedbasedonuser-levelrealitiessuchasmarketconditions,regulatorylimits,anduserpreferences(marketpotential).54FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVBOX7MappingDPV’sTechnicalPotentialDeterminingthetechnicalpotentialfordistributedphotovoltaic(DPV)developmentcanprovideananalyticfoundationforpolicyambitionsandprogramdesign.Techniquesgenerallycombinesatelliteandmeteorologicaldatawithdigitalsurfacemodels.TheWorldBank’sESMAPhascreatedafreeweb-basedtool—theGlobalSolarAtlas—thatcanhelpidentifypotentialsitesforsolarpowergenerationvirtuallyanywhereintheworld.Thetoolenablesuserstodeterminesolarenergypotentialforaspecificsite,howmuchelectricitywillbegenerated,andinwhattimeframe.Userscanincludedevelopers,utilities,plannerswithinutilities,orenergyministries.Solarenergyprojectscanbeplannedandevaluatedwithsiteanalyses,whichdetermineaveragesolarradiationatspecificlocations.Figure13showsascreenshotofthetoolinuse.FIGURE13:ASITEANALYSISUSINGTHEGLOBALSOLARATLASSite-specificvaluesChoosePVsystemtypeSource:https://globalsolaratlas.info/map.ESMAPdevelopedandispilotinganothertoolthatestimatesthesolarpowerpotentialofindividualrooftops.TheRooftopSolarMappingtool(rooftopsolar.energydata.info)wouldhelpcitiesdeterminethepotentialofrooftopDPV,takingintoconsiderationbuildingstructures,categoriesofbuildingownershipanduse,andneighborhoodlayouts.Userswouldbeabletodeterminehowmuchsolarcapacitycanbeinstalledonrooftopsandhowmuchpowereachinstallationcangenerateaccordingtoavailablerooftopspace,angles,andsolarirradiation.Individualbuildingsaremappedoutonafootprintpolygonextractedfromhigh-resolutionstereo-satelliteimagery,whichenablesthemeasurementofinstallablecapacity.(Seetheimagesusedonthecoverandbetweenchaptersofthisreportasexamples).Foreachbuildingrooftop,thegeographickWh/yearoutputvaluethatcorrespondstotherooftop’stiltandazimuthismultipliedbyinstallablecapacity.Theresultsareaggregatedbygeographiclocation,buildingcategory(commercial,industrial,single/multifamilyresidential),andothercategoryclustersthatprovideinsightstoDPVplanning.4:APPROACHESTOPOWERSYSTEMPLANNINGWITHDPV55HowtoreflectDPVinstudies?MostcapacityexpansionmodelstreatDPVasa“negativeload”thatmeetspartofgrossdemandforelectricity,leavinga“netload”orresidualdemandforgridelectricityfromothersources.21Inthisapproach,DPVoutputisdeductedfromthecurveoftheloadthatneedstobesuppliedbygridelectricity.Theexpansionmodelisthenrunusingthisadjusteddemand.22Thisapproachispragmaticwherethefocusisprimarilyonthetransmissionsystemanalysis,andwheredistributionlevelissuesareexpectedtobenegligibleorofsecondaryimportance.However,thisapproachimplicitlyassumesthatDPVcanfeedintothegridwithnocongestionandwithoutanyactivecontributiontosystemmanagement.Ifnofurtheranalysisisdone,thepowerplanwillnotcapturethefullrangeofpotentialbenefitsorchallengesfromDPVincludingitspotentialinteractionwithotherdistributedenergyresources(likeelectricvehiclesanddemandresponse)andthepowersystemmorebroadly.UtilitiesinLMICsoftenlackdataoroperationalguidanceonminimumloadperiods.Powersystemplansthusneedtoaccountforabroaderspectrumofpossibleoperatingconditions.Historically,distributiongridplanninghasofteninvolvedheuristicsorrulesofthumbforhostingcapacityasafixedvalue,forexample,basedonasubstation’stransformercapacity.SystemmodelsmaythenusethisruleofthumbtoimputehowmuchDPVwillbemaximallydeployedinaggregate.Moredetailedanalysiscan,incontrast,identifymoremeaningfulhostingcapacityestimatesbyexaminingwhathappenstovoltageatselectfeedersunderdifferentscenarios.RecentstudiesbyelectricutilitycompaniesshowthatsitingandsizingofDPVsystemscanbeoptimizedtomaximizetheirbenefits.Threeemergingapproachestosuchoptimizationanalysis,inorderofincreasingcomplexityandaccuracy,are:(1)approximateprocedures;(2)heuristicormetaheuristicapproaches;and(3)mixed-integerprogrammingtechniques(Bazrafshan&others2019).Box8describescommondistributionsystemplanningtoolsthatgobeyondanegativeloadapproach.Step4:CollatedatainputsCollectavailablerelevantdata.Inputswillvarydependingonthetypeofstudybeingdoneandthechoiceofmethodortool,butcouldinclude:systemdataonloads,thegrid,andexistingpowerplants;plusdataonavailableenergyresources,technologies,andprojecteddeploymentforDPVandotherDER(efficiency,storage,EV,gridservices)amongothernewgenerationsources.Wherepossible,mapgeospatialvariation.Checkthedataqualityandidentifyanynotablegapstofillorworkaround.DatascarcityandpoordataqualityarepressingchallengesinmanyLMICs.UtilitiesmayhaveinadequategeoreferencedinformationabouttheirgridsobtainedthroughGIS.Insomecases,distributiongridsareextendedonanadhocbasiswithoutproperplanning.Insuchsituations,planningforDPVpenetrationmaybecomemorechallengingsincetheutilitiesdonotknowexactlywherethefeedersareandwhichcustomerstheyserve.Datascarcityisparticularlyproblematicforloadforecastinganalyses.Together,thelackofdataandimproperlyplannedDPVdeploymentcanhavenegativeconsequencesforgridreliability,includingpoweroutages.Utilitieswithlimitedresourcescanmakenear-termDPVdeploymentforecasts21Netloadcanhavedifferentmeaningsdependingonthecontext.Hereitreferstodemandforbulkgridelectricityexcludingdemandforelectricityservedbydistributedsourcesandbulkvariablerenewablesources.Grossloadreferstototalend-userdemandforelectricityfromanysource,includingDPVorother“negativeloads.”Storage,anddemand-responsemeasuresmayalsobetreatedasnegativeloads.ItisimportanttonotethatDPVandconsumer-sidestoragereducedemandnotonlyforgridelectricityingeneralbutfrombulkrenewablestoo.22Foranexampleofthismethodologyinuse,forPakistan,seeWorldBank(2020).56FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVBOX8DistributionSystemPlanningToolsMostavailablecommercialtoolsfordistributionsystemplanningprovideforanalysesofpowerflow,powerquality,andfaultprotection.CommondistributionplanningtoolsincludeETAP,CYME,PSSSincal,Milsoft,Powerfactory,andSynergi.Someofthese,specificallyCYME,Synergi,andMilsoft,canbeusedtoassesshostingcapacityforDPV.AspecializedtoolforhostingcapacityanalysisisDistributionResourceIntegrationandValueEstimation(DRIVE)whichusesastreamlinedhostingcapacitymethoddevelopedbytheElectricPowerResearchInstitute(EPRI2015).ThismethodidentifiesoptimalDERlocations,mapsDERimpactsacrossthedistributionsystem,improvesinterconnectionscreening,andeventuallyinformsdistributionresourceplanswithDPVdata.ThismethodidentifieslocationswhereDPVismore(orless)likelytochallengegridoperationsandnode-,feeder-,andsystem-levelhostingcapacity.DRIVEcanbeusedinconjunctionwithotherdistributionplanningtools.Commercialtoolssuchasthosedescribedabovearethemostcommon.Beyondthese,open-sourcetoolshaveadditionalfunctionalitiesbeingdevelopedsuchassmartinvertercontrolsanddistributionsystemmanagementapplications.OneexampleisEPRI’sOpenDSStool,whichsupportsDERintegrationandgridmodernization.Furtheradvancementsofdistributionsystemplanningtoolsunderwayincludeincreasinghostingcapacitiesthroughsmartinvertersandinvertersettingsguidance.Note:Thisdoesnotcompriseanexhaustivelistofavailableproductsandservicesandshouldnotbereadasanendorsementofanytool.byextrapolatinghistoricaltrendsandusingopengeospatialplanningtoolssuchastheGlobalSolarAtlas.SeveralutilitieshavestartedincorporatingGISmappingoftheirgridandidentifyingthehostingcapacityofeachnodetofacilitateconnectionandstreamlineapprovalprocesses.Toimprovedatacollection,powersystemplannerscanadoptrelativelysimpleGIS-basedmethods.Forexample,staffcanfollowphysicallineswithamappingtool(suchasaglobalpositioningsystem)orusesatelliteimagery(e.g.,ofexistingorplannedconsumerlocations)togatherinputsfortheirdatabases.Utilitiescanalsoconductsurveys.TomonitorPVproduction,utilitiescanmandatemetersthatcapture,ataminimum,monthlyPVproductiontohelpwithdistributionnetworkplanning.MoresophisticatedapproachesrelyontheapplicationofaSCADAsystemtothedistributiongridandgrid-mappingtools.DuetoDPV’sabilitytogrowrapidly,deploymentforecastsmayneedregularupdatingtoreflectchangesinkeyfactors.FactorsthatcanimpactDPVprojectionsinclude:historicalDPVconnectionrequests;DPVsystemcosts;governmentDPVprocurementprograms;policiessuchasemissionstargetsorincentiveschemes;pricingreforms;andshiftsindemandpatternsfromelectrificationandurbanization.AssumptionsaboutallowableDPVfeed-inarrangementsmayaffectprojections.4:APPROACHESTOPOWERSYSTEMPLANNINGWITHDPV57Forhostingcapacityanalysis,thechoiceofperformanceindexorindicesiscritical.Anindexmaybebasedon:overvoltage,thermaloverloading,powerquality,and/orfaultprotection.Determinelimitsfortheindicesaccordingtolocalcodesorapplicablestandards.Identifyamenuofpotentialoptionstoenhancehostingcapacity(perChapter2).Makeappropriateassumptionstomatchtheagreedscopeforcurrentandprojectedloads;energyresources;demand-sideopportunities,bulkgenerationplants;andnetworks.Step5:DevisescenariosInputsareusedtosetupscenariostoillustratedifferentalternativefutures.Thesemayinclude:energyportfoliodevelopment,coveringallgenerationsources,demandresponse,andstorage;networks;andalternativesforsystemmanagement(e.g.,reserves,operationalmethods,andmarkets).Inaproductioncostmodel,scenariosmaydifferintermsofsystemflexibilitylevels.Inasystemexpansionstudy,scenariosmayvaryforfuelprices,technologycosts,etc.Considerbasecaseandalternativesforcomparison.ApplyforecastsforDPVdeployment.Sincedistributionfeedercharacteristicscanvarysignificantlywithinapowersystem,planningforDPVatthedistributionlevelreliesheavilyonscenariosbasedonmanyassumptions.Forthisreason,distributionlevelstudiesgenerallytakethelevelofvariablerenewablegeneration,andload,asaninputforscenariosratherthanaresultofoptimization.Atthetransmissionlevel,bycontrast,itiseasiertoassessandco-optimizethecapacitiesandlocationsoftransmissionnetworkswithbulkvariablerenewablestogether.Selecthostingcapacityenhancementoptionstoincludeinsimulations.Inidentifyingoptionstoenhancehostingcapacity,afewgeneralprinciplestokeepinmindinclude:(i)Considerawidevarietyofoptions;(ii)Considerwhichoptionsareallowedbyregulationandwhetherregulationsneedupdating;(iii)Considerthevalueofambitiousinvestmentoptionstoaccommodatelong-termdevelopments,versusincrementalchangesbasedononlyshort-termconditions;and(iv)Prioritizethemostcost-efficientsolutionsbeginningwithgridoptimizationfirst,thengridreinforcement,thengridexpansion,alsoknownastheNOVAprinciple.23Thethirdandfourthoftheaboveprinciplesneedtobebalancedagainsteachother.Gridoptimizationmayseemliketheleast-costoptionintheshorttermtoaccommodateincrementalchanges.However,insomecases,gridreinforcementandexpansionaremorecost-effectivethangridoptimizationfromalong-termperspective.Thisconsiderationisparticularlyimportantforgridinfrastructuregiventhelengthoftimeitcantaketoplanandbuild(years),itseconomiclifetime(decades),andtheexpenseandcomplicationofretrofittingascomparedtonewbuild.23ThistermNOVAisfromtheGermanlanguage:“NetzOptimierungVerstärkungAusbau”(gridoptimizationreinforcementenhancement).Germany’srenewableenergylawintroducedtheNOVAprincipleasacost-progressiveprocessforupgradingexistingelectricitygrids(Wagnerandothers2020).58FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVStep6:SimulateandassessscenariosScenarioscanthenbeusedforsimulationstoassess:(i)resourceadequacyandcapacityvalue(firmness);(ii)productioncostandsystemflexibility;(iii)networkadequacyatthetransmissionlevelanddistributionlevel;and(iv)systemdynamicsforgridstability.Thesesimulationscanbeconductedinanysequence,howevertheorderaslistedaboveisrecommended(Holttinen2018).Analysismayinclude:statisticaldataanalysisfortheimpactofDPVpoweronshorttermreserves;adequacyofgenerationresourcestoassessthecapacityvalueofDPV;productioncostsimulationstoseehowDPVimpactstheschedulinganddispatchofconventionalgenerationandsystemoperationalcosts;andnetworkadequacy.Calculatethedistributionperformanceindicesasafunctionoftheamountofdistributedgeneration.Runasuitableloadflowcalculationforthemodelwithincreasingamountsofdistributedgenerationbypre-definedstepsuntilperformanceindexresultsexceedallowablelimits.The“restricted”(uncontrolled)hostingcapacityisthemaximumamountofdistributedgenerationmodeledwithresultsnotexceedingallowablelimitsbeforeenhancements.Planningatthetransmissionlevelcanaccountforopportunitiestopromotealargerandmoreinterconnectedsystem,whichcanprovidergreateroptionsandflexibility.Gridstrengtheningandregionalinterconnectionscanexpandthebalancingareatosmooththenetloadcurveandprovidemoreflexibility,leveragingthegeographicdiversityofloadsandgenerationsources,suchasconnectingareaswithhighandlowlevelsofDPVinstallation.Step7:IterateandoptimizeExplorehowplansperformunderdifferentassumptions.Ifanysimulationgivesunacceptableresults,thesetupcanbevariedandsimulationsrunagain.Iterationscanidentifysystemenhancementsthatleadtoacceptableresultsacrosstherangeofassumptions.Plannerscanestimatetheimpactsofvaryinginputparameters(e.g.,changesinregulations)onDPVdeploymenttooptimizethepowersystemanalysis.Enhancementtechniquescanbechosenaccordingtothedefinedperformanceindexlimitandappliedconsideringtheoptimumratingandlocation.Loadflowcalculationscanbere-runconsideringtheenhancementstofindthecontrolled(enhanced)hostingcapacity,andonthisbasisdeterminetheremainingcapacityavailableonadistributiongrid.TheutilitycanalsolimitDPVdeploymentwhereappropriate.Optionsincludetolimitfeed-inthroughdynamiccurtailment,whereremotecontroltechnologiesareavailable,orelsebyapprovingonlyarrangementsthatfeednoneoftheoutputtothegrid.Inexpensiveinverterscanbeprogrammedtodispatchbattery-equippedDPVatsettimestoensuresmoothsystemoperations.Thissolutionhasbeenappliedeveninlow-incomecountriesmarkedbyfragility.Step8:MakeandissueplansOnceallsimulationsreturnacceptableresults,thenthedataanalysisandoutputsynthesiscaninformconclusionsaboutcosts,reinforcementneeds,stabilityconstraints,aswellaspotentialimprovementsforrulesandregulations.Identifyandevaluatecost-effectiveinterventionstoavoidordeferspecificequipmentupgrades,expediteinterconnectionprocedures,andenhancehostingcapacity.Publishandvalidateresults.TheoutputofanintegratedplanningapproachmaybeintheformofanIntegratedDistributionPlanor,forthepowersystematlarge,anIntegratedResourcePlan.Planningresultsanddeploymentplansshouldideallybesharedonuser-friendlyplatforms,suchasanonlineportal4:APPROACHESTOPOWERSYSTEMPLANNINGWITHDPV59onrelevantagencies’websites.Thisinformationcantheninformthedesignandtimingofnewprojects.Dependingonconfidentialityandcriticalinfrastructureconsiderations,theinformationmightbemadepublicorprovidedattherequestofDPVdevelopers.Step9:ImplementplansForDPVscale-up,planimplementationmaytypicallyinvolveproposing,solicitingandprocuringidentifiedinvestmentstoenhancehostingcapacity.Plansmayalsopointtotheneedforjust-in-timestudiesforspecificDPVinstallations,suchastoanalyzethebenefitsandcostsofproposedprojectsasspecificlocations.Thismayinvolveoutreachprogramsandmaterials,suchasauserguideforhostingcapacityanalysis,toguideconsumers’anddevelopers’preparationofnewDPVprojectstoalignwithoverallplans.Step10:MonitorandevaluateoutcomesDuringplanimplementation,monitortheeffectofchangestothesystemtovalidateexpectedimpactsoridentifyunexpectedresults.Powersystemoperatorsandotherstakeholderscanprovidevaluabledatatolearnfromevolvingexperienceandinformfutureefforts.Considerhowfrequentlyanupdatetoplansshouldoccurandwhattypesofchangesmighttriggeranupdate,suchasnewenergysectororemissionsreductionpolicies,anupdatetothegridcode,orsignificantchangesrelatedtoDERdeployment.CONCLUSION:BEYONDTECHNICALISSUESThisreporthasfocusedonthetechnicaldimensionsofgridoperationandplanningwithDPV.ButtoimplementaDPVrolloutprogram,itisessentialtoevaluatethecostsandbenefitsofdifferentDPVscenarios.Moreover,policiesareneededtoclearbarrierstodeployment,ensuretheeconomicviabilityofprojects,andprovideasoundfinancialbasisforinfrastructureandotherrelevantgenerationassets.Importantly,planningshouldnotbedoneinisolationfromregulationandpolicymaking.IfanalysisforplanningfindsthatDPVshouldbeconstrainedinsomeareastolimitthetechnicalorfinancialimpactsonthepowersystem,thiscaninformpolicysettings.IfDPViseconomicallyviableforacountryorregion,thenincentivestodevelopDPVshouldbesetinplaceandplansmadeaccordingly.Theseaspectsarecoveredinthethirdreportoftheseries:“DistributedPVEconomicsandPolicy.”60FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVANNEXA:TECHNICALDESCRIPTIONSOFNINEDPVUSECASESFORLMICsThisannexprovidestechnicaldescriptionsofnineusecases,orapplications,ofDPVrelevantforlow-andmiddle-incomecountries.Thefirstreportofthisseries(ESMAP2021)introducedtheseusecaseswithcountryexamples.TableCsummarizesthedefinitionofeachusecaseandtheirprevalenceacrosscountries,aswellasthedifferentfeedarrangementspossible.FiguresA1throughA9,furtherbelow,presentsingle-linediagramstoillustratehoweachusecasemaybeconfiguredinanelectricalengineeringframework.Abriefexplanationaccompanieseachfigure.Withinagivenusecase,technicalparametersmayvaryfromoneinstallationtoanother,andshouldbedesignedaccordingtolocalcircumstances.Keyparametersincludethetypeofequipmentandwiringconfigurations,aswellasfeedarrangementandmeters.Eachdiagramillustratesoneconceivableconfigurationforausecase.Inpractice,manydifferentconfigurationsarepossible.USECASE1:BILLREDUCTIONFigureA1showsafeed-somearrangementofDPVplusbatteryinstalledontheconsumersideofanetmeter.Feed-allandfeed-nonearrangementsarealsopossible.Thesystemcanhelpconsumersreducethemoneytheyarechargedintheirelectricitybillsinseveralways,comparedtoacasewithoutDPVandbattery(assumingthetariffstructureisthesameinallcases).First,DPVisusedtohelpreducetheoverallamountofgridelectricityconsumed.Second,theconsumermaybecompensatedforsurplusDPVoutputfedtothegridduringtimeswhenDPVoutputexceedsdemandonsite(assumingthebatteryisfullycharged).Third,thebatteryisusedtoadjustwhenandhowmuchgridelectricityisconsumedduringcertaintimesofdaytorespondtotime-of-usetariffsordemandcharges.Thisarrangementcannotbeusedforbackuppowerintheeventofapoweroutage,asthedirectconnectionoftheinverteroutputtotheutility-energizedlinesrequiresthattheinverterisagrid-followingtype,whichceasesproducingpowerintheeventofautilitypoweroutage.USECASE2:LEAST-COSTBACKUPFigureA2showsafeed-nonearrangementofsolarplusbatteryanddieselgeneratordifferentiatingpriorityloadssuchascomputers,lighting,medicalequipment,orrefrigeration.Non-priorityloadsremainconnectedtotheutilitygridandpoweredwhengridelectricityisavailable.Whenutilitypowerisavailable,allloadsaresuppliedbyutilityelectricitywithpriorityloadspoweredbyutilityelectricityroutedthroughtheinverter,24supplementedbyelectricityfromthePVarrayifthesunisshiningandbatteriesarefull.Intheeventofapoweroutage,electricitytopriorityloadsisautomaticallyswitchedovertoinverterpower(ingrid-formingmode)usingelectricitystoredinthebatteriesand,ifthesunisshining,electricityfromthesolarpanels.Typically,thetransitiontoinverterpowerwithlossofgridpowerhappenswithinabout40milliseconds,fastenoughthatthereislittleornodisruption.24SeeBox4foradescriptionofthisfunctionality.61TABLEC:NINEDPVUSECASESANDTHEIRPREVALENCEINLOW-ANDMIDDLE-INCOMECOUNTRIESUSECASEDEFINITIONPREVALENCEPOSSIBLEFEED1.BillreductionCommonARRANGEMENTDPVoffersaffordableelectricitybillstoCommonAny†2.�Least-costbackupconsumersbydisplacingelectricitythatwouldEmergingotherwisebepurchasedfromthegrid.Feed-noneor3.�Least-costEmergingfeed-somegenerationConsumersfacinggridelectricityoutageshaveDPV,typicallywithbatteries,toprovideOpportunityAny(typically4.�Transmissionimprovedservicewhileforegoingcostsandfeed-all)&distributiondependenceonfuelforbackupgenerators.OpportunityalternativeAnyDPVmaybeconsistentwithleast-costgenerationEmerging5.�Utilitybootstrapplanningforthepowersystem,especiallyinEmergingAnyplaceswithlandconstraints,giventheshortCommon6.�AncillaryservicestimelineforinstallationandlowlevelizedcostofFeed-someorelectricity.feed-all7.�CommunitysocialsupportDPVhelpsavoidordeferthemorecostlyAnyexpansionofnewpowerlines(alsoknownas8.�Financialloss“non-wirealternative”).ThisusecasedependsAny(typicallyreductiononcarefulgridplanningcoordinatedwithDPVfeed-none)systemlocationanddesign.Any9.�BoxsolutionAutilityinstallsDPV,withbatteriesand/orbackupgenerators(e.g.,asamicrogrid),toimproveserviceforatargetedsetofconsumersaspartofastrategytobuildtrustandincreasebillcollection.DPV,especiallyincombinationwithinvertersandbatteries,canprovidearangeofservicestothegrid,suchasfrequencyregulationandvoltagesupport.ThisusecaseimpliesclosecoordinationofDPVsystemswithgridoperations.Medium-to-largeDPVsystemscanbenefitalargenumberoflow-incomeconsumersthroughdirectconnectionsand/orsubscriptions.DPVreducesgridsalestocustomersinchronicarrearsandwhosesupplycannotbecutoff.PreassembledDPVsystem,quickandeasytoinstall,typicallywithabatteryorotherbackup,addressesurgentpowerneeds(e.g.,whenthegridbecomesunavailablefollowingadisaster)Source:Originalbyauthorsforthisreport.SeeESMAP(2021).Note:Well-establisheddeploymentsofDPVarecalled“common”usecases.Thosedeployedinonlyafewcircumstancesarecalled“emerging.”“Opportunity”usecasesarethosethatareyettobedeployed.†“Any”feedarrangementmeansaDPVsysteminthegivenusecasecouldbedesignedtofeedall,some,ornoneofitsgeneratedelectricitytothegrid.62FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVFIGUREA1:BILLREDUCTIONCASEREGULATOR-REGULATOR-PVARRAYBATTERYINVERTERINVERTERCIRCUITACBREAKERCIRCUITCIRCUITPVCHARGEBREAKERBREAKERARRAYREGULATORDCBATTERYINTERCONNECTIONDISTRIBUTIONPOINTPANELUTILITYGRIDNETMETER}LOADSFIGUREA2:LEAST-COSTBACKUPCASEREGULATOR-REGULATOR-PVARRAYBATTERYINVERTERINVERTERAC(FORM)CIRCUITACBREAKERCIRCUITCIRCUITPVCHARGEBREAKERBREAKERARRAYREGULATORDIESELBATTERYDCGENERATORAC(FOLLOW)TRANSFERSWITCHPRIORITYLOADSDISTRIBUTIONSUB-PANEL}NON-}PRIORITYPRIORITYLOADSLOADSCONSUMPTIONMETERUTILITYGRIDOPTIONALCURRENTSENSOR(FORFEED-NONE)INTERCONNECTIONPOINTANNEXA:TECHNICALDESCRIPTIONSOFNINEDPVUSECASESFORLMICs63Lossofmainpowercanbeusedtotriggeratransferswitch(orthetransferswitchcouldbemanuallyoperated),connectingtheinverter’sACinputtothedieselgenerator.Ifthebatterydischargesbelowaprogrammedthreshold,theinvertercansendasignal—typicallybyawirefromtheinverter(notshown)—tostartthedieselgenerator.BidirectionalfunctionalityofmostinvertersallowsforthebatteriestobechargedbyACelectricityfromtheutilitygridordieselgeneratorwhenenergized.Thiscanbeusefulforensuringadequatebackupbatteryreserves,andforequalizationcharging(controlledover-charging)whichcanhelpextendthelifetimeofcertaintypesofleadacidbatteries.Theinvertercanallowthedieselgeneratortosimultaneouslypowerloadsandchargethebattery,operatingthedieselengineatmoreefficient,higherpoweroutputlevels.Inpractice,thisconfigurationisconvenienttoretrofitintoexistinggrid-connectedbuildingsasitkeepsmuchoftheexistingwiringlargelyintact,withthebuilding’spre-existingdistributionpanelrepurposedasanon-priorityloadpanelandsupplyingtheinverterandpriorityloadssubpanelfromadedicatedcircuitinthenon-priorityloadpanel.Duringperiodswhentheutilitygridisoperationalandsolarsupplyexceedsdemandfromallloads,anenergymanagementdeviceisrequiredtomeasureutilitycurrentandcurtailinverteroutputasnecessarytomaintainthefeed-nonearrangement.SuchadevicetypicallycommunicateswiththeinverterviaBluetoothorethernetcable.A“feed-some”arrangementisalsopossiblewithnetmetering,inwhichcasethecurrentsensorisnotrequired.USECASE3:LEAST-COSTGENERATIONFigureA3showsafeed-allarrangementofutility-sidePVnexttoagridelectricityconsumer.ThePVsystemfeedsallgeneratedelectricityintothegrid,bypassingbuilding-levelelectricalconnections.EvenifthesystemFIGUREA3:LEAST-COSTGENERATIONCASEPVARRAYPVARRAYCIRCUITBREAKERINVERTERACUTILITYGRIDDCINTERCONNECTIONACCIRCUITPOINTBREAKERCONSUMPTIONMETERGENERATIONMETER}LOADS64FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVisinstalledonornearbyabuilding(whichservesasahosttothePVsystem),thePVsystemisnotapartofthebuilding’selectricalsystem.ThereisnodirectelectricalconnectionbetweenthePVsystemandanybuildinginfrastructureotherthanthroughthegrid.Theconfigurationrequirestwometers,onefortheelectricityfedfromPVintothegridandtheotheronthecustomersidemeasuringthecustomer’selectricityuse.USECASE4:TRANSMISSION&DISTRIBUTIONALTERNATIVEFigureA4showsafeed-somearrangementofDPVwithnetmetering.Thismaysuitasitewheregridelectricityisreliablebutalargemiddaypeakdemand(e.g.airconditioning)cannotbefullymetbythelocaldistributiongridcapacity.Inthisscenario,productionofelectricityonthesiteoftheconsumerhelpsthegridtodefernetworkupgradesthatwouldotherwiseberequiredtosupplyallelectricityfromthegrid.DuringtimeswhenDPVoutputexceedsdemandonsite,surplusDPVoutputisfedtothegrid.FIGUREA4:T&DALTERNATIVECASEPVPVARRAYCIRCUITBREAKERINVERTERARRAYACINTERCONNECTIONUTILITYGRIDPOINTDCACCIRCUITBREAKERNETMETER}LOADSANNEXA:TECHNICALDESCRIPTIONSOFNINEDPVUSECASESFORLMICs65USECASE5:UTILITYBOOTSTRAPFigureA5showsafeed-allarrangementofDPVplusbatteryinstalledonthegridsideofexistingregularconsumptionmeterstoimproveservicefortargetedconsumersinthehopesofimprovingcollections.Inthisscenario,thetargetedconsumersenjoylessgridoutagesthanbeforethankstotheDPVandbatterysystem,whichusesasimilararchitecturetotheleast-costbackupusecasesamplesabove.Thesystemmaybeownedbytheutility.(Ifownedbyathirdparty,agenerationmeterwouldbeneededtomeasureelectricityproductionfromtheDPV).USECASE6:ANCILLARYSERVICESFigureA6showsafeed-somearrangementidenticaltoFigureA1ofDPVplusbatteryandinvertertoprovideancillaryservicestothegrid,suchasfrequencyregulation,voltagesupport(includingreactivepower),anddemandresponse(includingramping).Asmartinverterallowsthisconfigurationtorespondwithinmillisecondstomaintaintheproperflowanddirectionofelectricity,addressimbalancesbetweensupplyanddemand,andhelpthesystemrecoverafterapowersystemevent.FIGUREA5:UTILITYBOOTSTRAPCASEREGULATOR-REGULATOR-PVARRAYBATTERYINVERTERINVERTERCIRCUITACAC(FORM)BREAKERCIRCUITCIRCUITPVCHARGEBREAKERBREAKERARRAYREGULATORUTILITYGRIDDCAC(FOLLOW)BATTERYINTERCONNECTIONCONSUMPTIONPOINTMETER}LOADS66FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVFIGUREA6:ANCILLARYSERVICESCASEREGULATOR-REGULATOR-PVARRAYBATTERYINVERTERSMARTCIRCUITINVERTERBREAKERCIRCUITCIRCUITACPVCHARGEBREAKERBREAKERARRAYREGULATORDCBATTERYINTERCONNECTIONDISTRIBUTIONPOINTPANELUTILITYGRIDNETMETER}LOADSUSECASE7:COMMUNITYSOCIALSUPPORTFigureA7showsagrid-sidefeed-allarrangementofDPVasacommunityschemenearanumberofconsumers,includingapartmentsthathaveonlyamasterconsumptionmeter.Inthisscenario,apartmenthouseholdspayfortheirelectricitybasedonsomemeasureotherthantheirspecificuse(e.g.floorarea).AgenerationmetermeasuresalltheelectricityproducedbythePVinstallation.Thisarrangementtypicallyrequirescooperationwiththeutilitytoimplementsubscriptionmodeforbilling(alsoknownasvirtualnetmetering),inwhichthePVproductionismeasuredandtheequivalenttotalamountofenergyisdividedupandappliedtooffsetenergyamountsintheutilitybillsofeachsubscribingcustomeraccordingtotheirdistributionofownershipofsharesinthecommunitysolarfacility.Inprinciple,thesolararraycouldbeanywhereintheutility’sserviceterritory;itneednotbelocatedinthebeneficiarycommunity.Theprogrammayprioritizelow-incomeusersasaformofsocialsupport.ANNEXA:TECHNICALDESCRIPTIONSOFNINEDPVUSECASESFORLMICs67FIGUREA7:COMMUNITYSOCIALSUPPORTCASEPVARRAYPVARRAYCIRCUITBREAKERINVERTERACDCAPARTMENT}ACCIRCUITLOADS}BREAKER}HOUSEHOLD}APARTMENTGENERATIONLOADSLOADSMETERAPARTMENTUTILITYGRIDLOADS}APARTMENTLOADSCONSUMPTIONMASTERMETERMETERINTERCONNECTIONPOINTCONSUMPTIONAPARTMENTAPARTMENTMETERLOADSLOADS}}MASTERMETER}HOUSEHOLDLOADS}}APARTMENTAPARTMENTLOADSLOADS68FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVUSECASE8:FINANCIALLOSSREDUCTIONFigureA8showsafeed-nonearrangementofDPVasmaybeusedtoreduceconsumptionofgridelectricityforconsumersinchronicarrears.Assumingtheutilitycannotdisconnectservicetothesedelinquentconsumers,theiruseofDPVhelpsreducethefinanciallossesincurredbytheutilityfromsellingthemgridelectricity.Inthisconfiguration,alltheelectricityproducedbytheinstallationissuppliedtotheconsumer.Nooutputisfedtothegrid.AcurrentsensorcommunicatesviaBluetoothorethernetcabletocurtailsolaroutputtopreventthePVarrayoutputfromexceedingthelocalload.(Feed-someorfeed-allarrangementsarepossiblewithdifferentconfigurations).FIGUREA8:FINANCIALLOSS-REDUCTIONCASEPVPVARRAYCHARGEINVERTERARRAYCIRCUITREGULATORACBREAKERDCLOADS}INTERCONNECTIONCONSUMPTIONCURRENTPOINTMETERSENSORUTILITYGRIDANNEXA:TECHNICALDESCRIPTIONSOFNINEDPVUSECASESFORLMICs69USECASE9:BOXSOLUTIONFigureA9showsafeed-somearrangementofDPVplusbatteryanddieselgeneratorasbackupinapre-assembledboxsolution,i.e.,ametalcabinet,orinlargecasesashippingcontainer,foreaseoftransportationandinstallation.Thisservesasanuninterruptiblepowersupplyforasitewithaconnectiontounreliablegridelectricity,providingtheabilitytoswitchovertobackuppowerwithintensofmillisecondsaftergridpowergoesdown.Aboxsolutionlikethiscanbedeployedquickly,improvingresilienceincaseofnaturaldisaster.Thebidirectionalinvertersupplieselectricitytoloadswhenthegridpowerisout,supportedbyabackupdieselgenerator.Whenutilitygridpowerisavailable,theinvertercanusegridelectricitytochargethebatteryifneeded.IfthebatteriesarefullychargedandPVpanelsproduceelectricityinexcessofloadthenelectricitycanflowouttotheutilitylines.(Feed-allandfeed-nonearrangementsarealsopossible).FIGUREA9:BOXSOLUTIONCASEBOXSOLUTIONREGULATOR-REGULATOR-PVARRAYBATTERYINVERTERINVERTERACCIRCUIT(FORM)BREAKERCIRCUITCIRCUITPVCHARGEBREAKERBREAKERACARRAYREGULATORDIESELDCGENERATORAC(FOLLOW)BATTERYTRANSFERSWITCHINTERCONNECTIONNETMETERDISTRIBUTIONPOINTPANELUTILITYGRID}LOADSANNEXB:DISTRIBUTIONGRIDTECHNICALSTANDARDSKeyrecentstandardsondistributedPVandotherdistributedenergyresourcesarelistedbelow,aspublishedbytheInstituteofElectricalandElectronicsEngineers(IEEE)andInternationalElectrotechnicalCommission(IEC).Thislistisnotintendedtobeexhaustive.Standardsareupdatedperiodicallytoreflectadvancesintechnologyandpracticalexperience.Consultrelevantauthoritiesforlatestdevelopments.IEEE1547seriesoninterconnectionofdistributedenergyresources:https://standards.ieee.org/products-services/icap/programs/der/•IEEE1547-2018,InterconnectionandInteroperabilityofDistributedEnergyResourceswithAssociatedElectricPowerSystemsInterfaces•IEEE1547,StandardforInterconnectingDistributedResourceswithElectricPowerSystems•IEEE1547.1-2020,StandardConformanceTestProceduresforEquipmentInterconnectingDistributedEnergyResourceswithElectricPowerSystemsandAssociatedInterfaces•IEEE1547.2,ApplicationGuideforIEEE1547StandardforInterconnectingDistributedResourceswithElectricPowerSystems•IEEE1547.3,GuideforCybersecurityofDistributedEnergyResourcesInterconnectedwithElectricPowerSystems•IEEE1547.4-2011,GuideforDesign,Operation,andIntegrationofDistributedResourceIslandSystemswithElectricPowerSystems•IEEE1547.6-2011,RecommendedPracticeforInterconnectingDistributedResourceswithElectricPowerSystemsDistributionSecondaryNetworks•IEEEP1547.7-2013,GuideforConductingDistributionImpactStudiesforDistributedResourceInterconnectionIEEEpowerelectronicsanddistributionsystem–relatedstandards•IEEE2030–2011,GuideforSmartGridInteroperabilityofEnergyTechnologyandInformationTechnologyOperationwiththeElectricPowerSystem(EPS),andEnd-UseApplicationsandLoads•IEEE1826-2020,StandardforPowerElectronicsOpenSystemInterfacesinZonalElectricalDistributionSystemsRatedAbove100kW•IEEE1676-2010,GuideforControlArchitectureforHighPowerElectronics(1MWandGreater)UsedinElectricPowerTransmissionandDistributionSystems71Regardingbatterystorage,IEChasseveralcommitteesworkingondocuments(standards,guides)addressingbatteryenergystorageimplementationissues,eitherdirectly,underthegeneralheadingofDERtechnologyormicrogriddeployment.Forexample,IEC62933.IEC61850isanimportantsmart-gridsstandardrelatingtosubstationautomation.TC57hasbeenpreparingadocumentonhowIEC61850canbeusedandextendedforelectricalbatteryenergystorageforseveralusecases.ThedocumentisrelatedtoIEC61850-7-420,whichincludestheextensionofobjectmodelsforenergystorage,byitselfandincombinationwithdistributedgeneration.72FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVABBREVIATIONSACalternatingcurrentAEMOAustralianEnergyMarketOperatorANSIAmericanNationalStandardsInstituteDAkkSDeutscheAkkreditierungsstelle[GermanAccreditationBody]DCdirectcurrentDERdistributedenergyresource(s)DPVdistributedphotovoltaic(s)DRIVEDistributionResourceIntegrationandValueEstimationEPRIElectricPowerResearchInstituteESMAPEnergySectorManagementAssistanceProgramGISgeographicinformationsystemGWgigawatt(s)HzhertzIEAInternationalEnergyAgencyIECInternationalElectrotechnicalCommissionIEEEInstituteofElectricalandElectronicsEngineersILRInverterloadratioIRPIntegratedResourcePlanISOInternationalOrganizationforStandardizationJAS-ANZJointAccreditationSystemofAustraliaandNewZealandkmkilometerkWkilowattkWhkilowatt-hourLMICslow-andmiddle-incomecountriesMWmegawattNECNationalElectricalCodeNOVANetzOptimierungVerstärkungAusbau[gridoptimizationreinforcementenhancement]SCADAsupervisorycontrolanddataacquisitionSTATCOMstaticsynchronouscompensatorT&DtransmissionanddistributionVArvolt-amperereactiveVPPvirtualpowerplantVREvariablerenewableenergy73GLOSSARYactivepowerTheproportionofelectricityflowinginanACnetworkthatresultsinanettransferofenergy.(Comparereactivepower).ancillaryservicesThisisanumbrellatermforallthecapabilitiesrequiredinapowersystem,apartfromactivepowergeneration,toreliablymeetdemand.Thesecomprisetoolsandprocedurestomaintainfrequencyandvoltagewithinnominalranges,andrestartthesystemafteramajorblackout.Ancillaryservicescanbeprovidedacrossalllevelsofthepowersystembygenerationsources,storagesystems,inverters,andotherequipment.Indifferentcontexts,provisionofsomeservicesmaybemandatory(e.g.,gridcodeconnectionrequirementsforDPVinverters),oroptionalandincentivizedbyremuneration.Forexample,DPVmaybeabletoprovideseveraldistributionsystemservices,includingtargetedloadreductionincapacity-constrainedareasofthenetwork(distributioncapacity),feeder-levelvoltagemanagement(voltagesupport),reductionsinthefrequencyanddurationofoutages(reliabilityorback-tie),andimprovedrecoverytimefromoutagesorsystemdisturbances.anti-islandingFortheprotectionofutilityworkers,generationresources(includingdistributedgenerationresources)mustbeabletodetectblackoutsanddisconnectsoasnottoformanisolatedisland.Thiscapabilityisreferredtoasanti-islanding.bidirectionalmeterAdevicethatmeasuresbothenergyfedtoagridandenergyconsumed.Meterdesignsvary.Metersthatmeasuretwoseparategrossvolumescanbeusedforgrossmetering,netmetering,ornetbilling.Incontrast,abidirectionalmeterthatonlymeasuresnetenergyfedtothegridandnetenergyconsumedfromthegridcanbeusedonlyfornetmeteringornetbilling.blackstartThecapabilityofageneratortocommenceoperationswithoutrelyingonanexternalpowersourceforstartingup.controllabilityThepossibilitytointerveneinasystemthatisinastateofdeviancefromatargetrange.Thisisafundamentalconceptofcontroltheory(i.e.,thescienceofmanagingdynamicsystems)alongwith“visibility.”distributedPVAnyphotovoltaicslocatedwithornearconsumersconnectedtoanelectricitygrid.Thisdefinitionimpliesnominimumormaximumsize.SystemscanrangefromasinglePVpanelof250watts,forexample,uptotensofmegawatts(MW)capacity.Inotherliterature,thetermmayrefertooff-gridPVsystems.feed-inarrangementDenoteswhetheraDPVorotherdistributedgenerationsystemisconfiguredtofeedsome,none,orallitspoweroutputtothegrid,versususeoftheoutputonsiteforself-supply.feederSegmentofthedistributiongridthatconnectsindividualsmallerconsumerstoalargerpowerline.gridcodeThefullsetofoperationalandtechnicalrulesgoverningapowersystem,includingstandardsforDPVsystemstoconnecttothegrid.grid-formingThefunctionofaninvertertoactivelycontrolfrequencyandvoltageoutput,withoutneedforanexternalACsource.Thisfunctionmaybeservedbyagrid-forminginverteroramultimodalinvertoringrid-formingmode.grid-followingThefunctionofaninvertertotrackthevoltageangleofanexternalsource(e.g.,thegrid)tocontroltheoutputsothatitsynchronizestotheexternalsource,injectingcurrentinsyncwiththe74externalwaveform.Thisfunctionmaybeprovidedbyagrid-followinginverteroramultimodalinvertoringrid-followingmode.grossmeteringMeasurementofallenergyfedtothegrid,withseparatemeasurementofallenergyconsumedfromthegrid.Afeed-allarrangementnecessarilyhasgrossmeteringofenergyproduced,sinceitisallfedtothegrid.Inafeed-allarrangement,aproductionmeterservesthispurpose.Grossmeteringisalsoanoptionforfeed-somearrangementsandcanbeachievedwithdualmetering,implyingtheuseoftwoseparatemeterdevices,orwithasinglebidirectionalmeter.Grossmeteringfacilitatesnetbillingforfeed-somearrangements.harmonicsACgridvoltageandcurrentideallyfollowasinusoidalwaveformatastablefrequency(50Hzor60Hzdependingonthepowersystem).Certaindevices—includinginverters—candistortthisidealshape.Theeffectofsuchdistortionscanbedescribedbyoverlayingasetofwaveformsthatareintegermultiplesofthetargetsystemfrequency.Theseadditionalwaveformsarecalledharmonics.Harmonicscannegativelyimpactequipment,suchasincreasedheatingofconductorsortransformers.hostingcapacityTheestimatedmaximumamountorrangeofdistributedgenerationpossibletointegrateintoanelectricalnetworkwhilekeepingwithinspecifiedoperationalperformancelimits(e.g.,overvoltage,thermaloverloading,powerquality,protectionproblems)beforeorafterenhancementtechniques(e.g.,reactivepowerandvoltagecontrol,activepowercurtailment,energystoragetechnologies,networkreconfiguration,gridreinforcements,andharmonicsmitigation).islandingCapabilityofadistributedgeneratortomaintainserviceinasmallportionofthegridevenifthemaingridexperiencesanoutage.Islandingisusuallyundesiredbecauseitcanharmutilityworkersstrivingtoreestablishservice.Microgridsaredesigneddeliberatelytohaveislandingcapabilities,butinawaythatdoesnotnegativelyinfluencethemaingrid.loadbalancingMeasurestomatchintimethedemandforandsupplyofpower.ForDPV,thiscaninvolveoptimizingDPVpanelsize,panelangles,andinvertershaving,sothatDPVoutputcoincideswiththeexpectedtimeandlevelofloads.ItcanalsoinvolvecalibratingloadstobettermatchDPVoutput(e.g.flexiblecoolersorheaters).EnergystoragesystemscanperformloadmatchingaspartofaDPVsystemoralone.microgridAsmallgridsystemwithitsownpowergenerationsourcestoserveoneormoreconsumerfacilities,typicallywithaninterconnectiontoamaingridandcapableofoperatingindependentlyduringanoutageofthemaingrid.minigridAsmallgridsystemtoserveoneormoreconsumerfacilities,typicallyinanoff-gridsetting.netbillingSeparatemeasurementandpricingofenergyconsumedfromthegridandenergyfedtothegridunderafeed-somearrangement(thatis,someDPVenergyisfedtothegrid,andsomeDPVenergyisconsumed),eachnetofself-supply.Typicallyaccountedwithabidirectionalmeter.netenergyThevectorsumofenergyconsumedandenergyfedbytheconsumertothegridoveragivenperiod(forexample,hour,day,month,orbillingcycle).Thesumforthegivenperiodmaybeanetfeed-in(“credits”fromtheconsumers’perspective,sometimescalled“excess”energy),netconsumption,orzero(ifthefeed-inandgridconsumptionamountshappentobeequal).netloadNetloadmayhavedifferentspecificmeaningsbutrefersheregenerallytodemandforgridelectricityexcludingdemandservedbydistributedand/orbulkvariablerenewablesources.Grossloadreferstototalend-userdemandforelectricityfromanysource,includingDPVorother“negativeloads.”Storage,anddemand-responsemeasuresmayalsobetreatedasnegativeloads.DPVandconsumer-sidestoragereducedemandnotonlyforgridelectricityingeneralbutfrombulkrenewablestoo.GLOSSARY75netmeterAmeterofnetenergy.Thesimplestversionofanetmeterisacommonretailmeterthatspinsforwardforeachunitofenergyconsumedfromthegridandthatcanspinbackwardswhenenergyisfedtothegrid.Withsuchameter,calculatingnetenergyinvolvescomparingthemeterreadingattwodifferentpointsintime(e.g.,onceeachmonth).Themorefrequentlysuchameterisread,themoreinformationisavailabletoinformbillingoptions.Suchametercantheoreticallybeusedtoestimatetotalenergyconsumedfromthegridortotalenergyfedtothegridwhenreadingsaretakencontinuouslyinrealtime.netmeteringTheprocessofaccountingforDPVgenerationfedtoagridusinganetmeterorequivalent,suchthatenergyfedtothegridiscompensatedatthesamerateastheenergycomponentoftheretailelectricitytariffforthegivenperiod(retailparitycompensation).Inpractice,therearemanyformsofnetmetering,anddifferentjurisdictionsapplythetermindifferentways.non-synchronousgenerationProductionofelectricitythatisnotsynchronizedtothegrid,namelyDCpower(e.g.,fromPV),orACpoweratafrequencyotherthanthegrid’sfrequency.Invertersconvertnon-synchronizedACorDCpowerintosynchronizedACpower.Bycontrast,synchronousgeneration(suchasfromthermalpowerplants)produceACelectricityatthegrid’sfrequencywithouttheneedforaninverter.penetrationTheamountofaparticulargenerationconnectedtoapowersystem.reactivepowerTheproportionofelectricityflowinginanACpowernetworkthatisneededtocontinuouslychargeanddischargetheelectromagneticfieldsinandaroundelectricalequipment.Reactivepoweroscillatesbackandforthinthegridanddoesnotcontributetoanettransferofenergy.ride-throughThecapabilityofanelectricgeneratortostayconnectedtothegridandtocontinueoperatingduringsystemdisturbances,withinarangeofconditions,tohelpavoidpoweroutages.ForDPV,thiscapabilityisprovidedbyagrid-connectedinverter.GridcodesmayrequireDPVinverterstobeabletoridethroughshort-termlow-voltageevents,forexample,whichmayoccuratthemomentwhenlargeloadsareconnectedtothegrid.underfrequencyload-sheddingrelaysDevicethatautomaticallydisconnectsaportionofadistributiongridduringperiodsofgenerationshortfalltoavoidalarge-scaleblackout.Iffrequencyfallsbelowasetthreshold,therelaymeasureslocallyanddisconnects.utilityElectricityservicecompany.ForDPV,autilitytypicallyreferstoadistributioncompanyoraverticallyintegratedutility,beingacompanythatownsassetsacrosstheelectricitysupplychain(generation,transmission,distributionandretail)withinagivenservicearea.virtualpowerplant(VPP)Avirtualpowerplantisanetworkofdecentralizedgeneratingunits,consumersofflexiblepower,andstoragesystems,allinterconnectedanddispatchedthroughcentralcontrolasiftheywereonepowerplantyetindependentinoperationandownership.visibilityTheabilitytoknowthestateofasystemorprocess,asafundamentalconceptofcontroltheory(i.e.,thescienceofmanagingdynamicsystems)alongwith“controllability.”SeealsoUSEnergyInformationAdministration(EIA)glossaryathttps://www.eia.gov/tools/glossary/.76FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVREFERENCESAEMO(AustralianEnergyMarketOperator).2019.“TechnicalIntegrationofDistributedEnergyResources:ImprovingDERCapabilitiestoBenefitConsumersandthePowerSystem.AReportandConsultationPaper.”Australia.www.aemo.com.au/-/media/Files/Electricity/NEM/DER/2019/Technical-Integration/Technical-Integration-of-DER-Report.pdfAEMO.2021.“VirtualPowerPlantDemonstrations:KnowledgeSharingReport#4.”Australia.www.aemo.com.au/initiatives/major-programs/nem-distributed-energy-resources-der-program/der-demonstrations/virtual-power-plant-vpp-demonstrationsAznar,Alexander,andSherryStout.2018.“USAIDDistributedPVBuildingBlocks:InterconnectionProcesses,Standards,andCodes.”UnitedStates.www.cleanenergyministerial.org/sites/default/files/documents/udaid-dpv-building-blocks_interconnection_may_finance_business-models.pdfBalouktsis,Ioannis,JiangZhu,RolandBrundlinger,ThomasR.Betts,andRalphGottschalg.2008.“OptimisedInverterSizingintheUK.”Paperpresentedatthe4thPhotovoltaicScienceApplicationandTechnology(PVSAT-4)Conference,UniversityofBath,April2008.UnitedKingdom.https://repository.lboro.ac.uk/articles/conference_contribution/Optimised_inverter_sizing_in_the_UK/9557000Bazrafshan,Mohammadhafez,LikhithaYalamanchili,NikolaosGatsis,andJuanGomez.2019.“StochasticPlanningofDistributedPVGeneration.”Energies12(3):459.Switzerland.doi.org/10.3390/en12030459BDEW(GermanAssociationofEnergyandWaterIndustries).2021.SystemStabilityOrdinance[originalGerman‘Systemstabilitätsverordnung’].Germany:BundesverbandderEnergie-undWasserwirtschaft.www.bdew.de/energie/systemstabilitaetsverordnung/Boyd,Erin.2016.“PowerSystemModelling101.”TechnicalAssistance.UnitedStates:DepartmentofEnergy.www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2016/02/f30/EPSA_Power_Sector_Modeling_FINAL_021816_0.pdfDing,Fei,YingchenZhang,JeffreySimpson,AndreyBernstein,andSubramanianVadari.2020.“OptimalEnergyDispatchofDistributedPVsfortheNextGenerationofDistributionManagementSystems.”IEEEOpenAccessJournalofPowerandEnergy7:287–95.UnitedStates.doi.org/10.1109/OAJPE.2020.3009684EnergyTransitionInitiative.2017.“SunScreens:MaintainingGridReliabilityandDistributedEnergyProjectViabilitythroughImprovedTechnicalScreens.”Discussionpaper.DOE/GO-102017-4946.UnitedStates:DepartmentofEnergy.www.nrel.gov/docs/fy17osti/67633.pdfEPRI(ElectricPowerResearchInstitute).2015.“IntegrationofHostingCapacityAnalysisintoDistributionPlanningTools.”UnitedStates:EPRI.www.epri.com/research/products/000000003002005793EPRI.2018.“RecommendedSmartInverterSettingsforGridSupportandTestPlan.”UnitedStates:EPRI.www.nationalgridus.com/media/pdfs/microsites/mass-solar/recommended-smart-inverter-settings-for-grid-support-and-test-plan_-interim-report.pdfESMAP(EnergySectorManagementAssistanceProgram).2019.“UsingForecastingSystemstoReduceCostandImproveDispatchofVariableRenewableEnergy.”TechnicalGuide.UnitedStates:WorldBank.www.esmap.org/using-forecasting-systems-to-reduce-cost-improve-dispatchESMAP.2020a.PrimerforCoolCities:ReducingExcessiveUrbanHeat.KnowledgeSeries031/20.UnitedStates:WorldBank.www.esmap.org/primer-for-cool-citiesreducing-excessive-urban-heat77ESMAP.2020b.DeployingStorageforPowerSystemsinDevelopingCountries:PolicyandRegulatoryConsiderations.UnitedStates:WorldBank.www.esmap.org/deploying-storage-for-power-systems-in-developing-countriesESMAP.2021.FromSuntoRooftoGrid:DistributedPVinEnergySectorStrategies.TechnicalReport017/21.UnitedStates:WorldBank.www.esmap.org/esmap-from-sun-to-roof-to-grid-distributed-pvESMAP.2022.MiniGridsforHalfaBillionPeople:MarketOutlookandHandbookforDecisionMakers.UnitedStates:WorldBank.www.esmap.org/mini_grids_for_half_a_billion_peopleEto,JosephH.,RobertLasseter,DavidKlapp,AmritKhalsa,BenSchenkman,MaheshIllindala,andSuryaBaktiono.2018.“TheCERTSMicrogridConcept,asDemonstratedattheCERTS/AEPMicrogridTestBed.”TechnicalReport.Berkeley,CA:LawrenceBerkeleyNationalLaboratory.Georgilakis,PavlosS.,andNikosD.Hatziargyriou.2015.“AReviewofPowerDistributionPlanningintheModernPowerSystemsEra:Models,MethodsandFutureResearch.”ElectricPowerSystemsResearch121(April):89–100.Netherlands.doi.org/10.1016/j.epsr.2014.12.010Hailu,Tsegay,LaurensMackay,LauraRamirez-Elizondo,JunyinGu,andJanA.Ferreira.2015.“WeaklyCoupledDCGridforDevelopingCountries:‘LessIsMore’.”PresentedattheAFRICONConference,September2015.Ethiopia.doi.org/10.1109/AFRCON.2015.7331939.Hanson,Dana,OmarAl-Juburi,JeffMiller,andBradHartnett.2019.“InanAcceleratedEnergyTransition,CanUSUtilitiesFast-TrackTransformation?”UnitedStates:GridWiseAllianceandEYCollaboration.https://gridwise.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Perspectives-on-a-Future-Distribution-System.pdfHolttinen,Hannele,ed.2018.RecommendedPracticesforWindandPVIntegrationStudies.InternationalEnergyAgencyTechnologyCollaborationProgrammeforCo-operationintheResearch,DevelopmentandDeploymentofWindEnergySystems(IEAWind)andPhotovoltaicPowerSystemsProgramme(IEAPVPS)ExpertGroup.Report16.2,Secondedition.France.https://iea-pvps.org/key-topics/recommended_practises_for_wind_and_pv_integration_studies/Horowitz,Kelsey,ZacPeterson,MichaelCoddington,FeiDing,BenSigrin,DanishSaleem,SaraE.Baldwin,BrianLydic,SkyStanfield,NadavEnbar,StevenColey,AdityaSundararajan,andChrisSchroeder.2019.AnOverviewofDistributedEnergyResourceInterconnection:CurrentPracticesandEmergingSolutions.TechnicalReportNREL/TP-6A20-72102.UnitedStates:NationalRenewableEnergyLaboratory(NREL).www.nrel.gov/docs/fy19osti/72102.pdfIEA(InternationalEnergyAgency).2018.ThailandRenewableGridIntegrationAssessment.PartnerCountrySeries.France:IEA.www.iea.org/reports/partner-country-series-thailand-renewable-grid-integration-assessment.IEA.2022a.“SolarPV.”France:IEA.www.iea.org/reports/solar-pv.IEA.2022b.WorldEnergyOutlook2022.France:IEA.www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022.IEA.2022c.UnlockingthePotentialofDistributedEnergyResources:PowerSystemOpportunitiesandBestPractices.France:IEA.www.iea.org/reports/unlocking-the-potential-of-distributed-energy-resources.IEA.2023.“PhotovoltaicPowerSystemsProgramme(PVPS).”France:IEATechnologyCollaborationProgram.https://iea-pvps.org/IEEE(InstituteofElectricalandElectronicsEngineers).2018.“IEEEStandardforInterconnectionandInteroperabilityofDistributedEnergyResourceswithAssociatedElectricPowerSystemsInterfaces.”78FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVStandard1547-2018(RevisionofIEEEStd1547-2003).UnitedStates:IEEE.doi.org/10.1109/IEEESTD.2018.8332112.IFC(InternationalFinanceCorporation).2014.“HarnessingEnergyfromtheSun:EmpoweringRooftopOwners.WhitePaperonGrid-ConnectedRooftopSolarPhotovoltaicDevelopmentModels.”India:IFC.https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/08bbf563-b5e7-5462-88d1-84c6397db6baIFC.2019.TheDirtyFootprintoftheBrokenGrid:TheImpactsofFossilFuelBack-UpGeneratorsinDevelopingCountries.UnitedStates:IFC.www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/mgrt/20190919-full-report-the-dirty-footprint-of-the-broken-grid.pdfIRENA(InternationalRenewableEnergyAgency).2018.InsightsonPlanningforPowerSystemRegulators.UnitedArabEmirates:IRENA.www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2018/Jun/IRENA_Insights_on_planning_2018.pdfIRENA.2022.GridCodesforRenewablePoweredSystems.UnitedArabEmirates:IRENA.www.irena.org/publications/2022/Apr/Grid-codes-for-renewable-powered-systems.Islam,F.Rabiul,KabirAlMamun,andMaungThanOoAmanullah.2017.SmartEnergyGridDesignforIslandCountries:ChallengesandOpportunities.Switzerland:Springer.Ismael,SherifM.,ShadyH.E.AbdelAleem,AlmoatazY.Abdelaziz,andAhmedF.Zobaa.2019.“State-of-the-ArtofHostingCapacityinModernPowerSystemswithDistributedGeneration.”RenewableEnergy130(January):1002–20.Netherlands.doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.07.008.Kraiczy,Markus.2021.PVasanAncillaryServiceProvider.ReportIEA-PVPST14-14:2021.France:InternationalEnergyAgencyPhotovoltaicPowerSystemsProgramme(IEAPVPS).https://iea-pvps.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/IEA-PVPS_T14_14_2021_PV_ancillary_service_provider_IEA_PVPS_report.pdfKroposki,Benjamin.2021.“TheNeedforGrid-FormingInvertersinFuturePowerSystems.WhyThisisTheMostCriticalTopictoAddresstoAchieve100%CleanEnergyGoals.”UnitedStates:UniversalInteroperabilityforGrid-FormingInverters(UNIFI)Consortium.https://youtu.be/ZaHkhkYxWwc?si=wXGEkE_9ZcAv5XSf&t=174.Le,HangThi-Thuy,EleonoraRivaSanseverino,Dinh-QuangNguyen,MariaLuisaDiSilvestre,SalvatoreFavuzza,andManh-HaiPham.2022.“CriticalAssessmentofFeed-InTariffsandSolarPhotovoltaicDevelopmentinVietnam.”Energies15(2):556.UnitedStates.doi.org/10.3390/en15020556.Le,Lam.2022.“AfterRenewablesFrenzy,Vietnam’sSolarEnergyGoestoWaste.”AlJazeeraMediaNetwork,May18,2022.Qatar.www.aljazeera.com/economy/2022/5/18/after-renewables-push-vietnam-has-too-much-energy-to-handle.Lin,Yashen,JosephH.Eto,BrianB.Johnson,JackD.Flicker,RobertH.Lasseter,HugoN.VillegasPico,Gab-SuSeo,BrianJ.Pierre,andAbrahamEllis.2020.ResearchRoadmaponGrid-FormingInverters.TechnicalreportNREL/TP-5D00-73476.UnitedStates:NationalRenewableEnergyLaboratory.www.nrel.gov/docs/fy21osti/73476.pdfLindl,Tim,KevinFox,AbrahamEllis,andRobertBroderick.2013.“IntegratedDistributionPlanningConceptPaper.”UnitedStates:InterstateRenewableEnergyCouncil(IREC).https://irecusa.org/resources/integrated-distribution-planning-concept-paper/Magal,Akhilesh,TobiasEngelmeier,GeorgeMathew,AshwinGambhir,ShantanuDixit,AnilKulkarni,B.G.Fernandes,andRanjitDeshmukh.2014.GridIntegrationofDistributedSolarPhotovoltaics(PV)inREFERENCES79India:AReviewofTechnicalAspects,BestPracticesandtheWayForward.India:PrayasEnergyGroup.https://energy.prayaspune.org/our-work/research-report/grid-integration-of-distributed-solar-photovoltaics-pv-in-india-a-review-of-technical-aspects-best-practices-and-the-way-forwardMarcy,Cara.2018.“SolarPlantsTypicallyInstallMorePanelCapacityRelativetoTheirInverterCapacity.”UnitedStates:EnergyInformationAdministration(EIA).www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=35372McAllister,Richard,DavidManning,LoriBird,MichaelCoddington,andChristinaVolpi.2019.NewApproachestoDistributedPVInterconnection:ImplementationConsiderationsforAddressingEmergingIssues.TechnicalReportNREL/TP-6A20-72038.UnitedStates:NationalRenewableEnergyLaboratory.McConnell,Dylan,SimonHolmesàCourt,StevenTan,andNikCubrilovic.2021.AnOpenPlatformforNationalElectricityMarketData.Australia.https://opennem.org.au.MicrogridKnowledge.2019.“BigWinforLocalEnergy:FirstVirtualPowerPlantSnagsContractinUSWholesaleCapacityAuction.”UnitedStates.https://microgridknowledge.com/virtual-power-plant-wholesale-sunrun/.NREL(NationalRenewableEnergyLaboratory).2015.WesternWindandSolarIntegrationStudy.UnitedStates:NREL.https://www.nrel.gov/grid/wwsis.htmlNREL.2023.PVWatts®Calculator.UnitedStates:https://pvwatts.nrel.gov/index.phpPalmintier,Bryan,RobertBroderick,BarryMather,MichaelCoddington,KyriBaker,FeiDing,MatthewReno,MatthewLave,andAshwiniBharatkumar.2016.OnthePathtoSunShot:EmergingIssuesandChallengesinIntegratingSolarwiththeDistributionSystem.TechnicalReportNREL/TP-5D00-65331.UnitedStates:NationalRenewableEnergyLaboratory.https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy16osti/65331.pdf.Papadimitriou,Christina,VasilisKleftakis,andNikosHatziargyriou.2018.“DCMicrogridsforEnergyCommunitiesintheDevelopingWorld.”PresentedattheInternationalConferenceandExhibitiononElectricityDistribution(CIRED),June2018.Slovenia.https://www.cired-repository.org/handle/20.500.12455/1104.Pulumbarit,Mike.2023.“UnderstandingDC/ACRatio.”UnitedStates:AuroraSolarHelioScope.https://help-center.helioscope.com/hc/en-us/articles/8198321934867-Understanding-DC-AC-Ratio.Maisch,Marjia.2019.“NationalProgramtoDriveVirtualPowerPlantParticipationinAustralia.”PVMagazine,July31,2019.Germany.www.pv-magazine.com/2019/07/31/national-program-to-drive-virtual-power-plant-participation-in-australiaRylander,Matthew,RobertJ.Broderick,MatthewJ.Reno,KarinaMunoz-Ramos,JimmyE.Quiroz,JeffSmith,LindseyRogers,RogerDugan,BarryMather,MichaelCoddington,PeterGotseff,andFeiDing.2015.Alternativestothe15%Rule.UnitedStates:EPRI,SandiaNationalLaboratories,andNREL.Siemens.2019.“PuertoRicoIntegratedResourcePlan2018–2019:DraftfortheReviewofthePuertoRicoEnergyBureau.”SiemensPTIReportRPT-015-19.UnitedStates:Siemens.https://energia.pr.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2019/06/2-IRP2019-Main-Report-REV2-06072019.pdf.Singh,Rashi,RishabhSethi,andRobinMazumdar.2019.“SolarRooftop:PerspectiveofDiscoms.”India:TheEnergyResourcesInstitute(TERI)Press.Stanfield,Sky,andStephanieSafdi.2017.“OptimizingtheGrid:Regulator’sGuidetoHostingCapacityAnalyses.”UnitedStates:InterstateRenewableEnergyCouncil(IREC).https://irecusa.org/resources/optimizing-the-grid-regulators-guide-to-hosting-capacity-analyses/80FROMSUNTOROOFTOGRID:POWERSYSTEMSANDDISTRIBUTEDPVStanfield,Sky,YochiZakai,andMatthewMcKerley.2021.“KeyDecisionsforHostingCapacityAnalyses.”UnitedStates:InterstateRenewableEnergyCouncil(IREC).https://irecusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/IREC-Key-Decisions-for-HCA.pdfStetz,Thomas,ManoelRekinger,andIoannisTheologitis.2014.“TransitionfromUni-DirectionaltoBi-DirectionalDistributionGrids:ManagementSummary.”France:InternationalEnergyAgency(IEA)PhotovoltaicPowerSystemsProgramme(PVPS)Task14Subtask2.https://iea-pvps.org/key-topics/transition-from-uni-directional-to-bi-directional-distribution-grids-iea-pvps-task-1403-2014/.Tomar,Anuradha.2020.“ControlArchitecturesforRuralStandaloneMicrogrids—AComprehensiveReview.”Presentedat2021IEEERuralElectricPowerConference(REPC),April2021.UnitedStates.http://doi.org/10.1109/REPC48665.2021.00014Wagner,Henrik,JonasWussow,andBerndEngel.2020.“NOVAMeasuresinSuburbanLowVoltageGridswithanInhomogeneousDistributionofElectricVehicles.”ConferencePaperpresentedatthe4thE-MobilityPowerSystemsIntegrationSymposium,November2020.Slovenia.www.researchgate.net/publication/346039201.Weaver,JohnFitzgerald.2019.“AWayOversizedDC:ACRatioSeenintheWild!”PVMagazine,July24,2019.UnitedStates.https://pv-magazine-usa.com/2019/07/24/a-way-oversized-dcac-ratio-seen-in-the-wild/WorldBank.2016.“ElectrifyingMyanmar:ChallengesandOpportunitiesPlanningNation-WideAccesstoElectricity.”UnitedStates:WorldBank.https://energypedia.info/images/c/cc/WB_2016_Electrifying_Myanmar_Opportunities_Challenges.pdfWorldBank.2020.“VariableRenewableEnergyIntegrationandPlanningStudy.”PakistanSustainableEnergySeries.UnitedStates:WorldBank.https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/884991601929294705/pdf/Variable-Renewable-Energy-Integration-and-Planning-Study.pdfWorldBank.2022.VietnamCountryClimateandDevelopmentReport.CountryClimateandDevelopmentReports(CCDR)Series.UnitedStates:WorldBank.http://hdl.handle.net/10986/37618WorldBank.2021.“SolarPVForecastingTool.”UnitedStates:WorldBank.https://solarforecasting.energydata.info/REFERENCES81RooftopsanalyzednearsubstationinManila,PhilippinesESMAPMISSIONTheEnergySectorManagementAssistanceProgram(ESMAP)isapartnershipbetweentheWorldBankandover20partnerstohelplow-andmiddle-incomecountriesreducepovertyandboostgrowththroughsustainableenergysolutions.ESMAP’sanalyticalandadvisoryservicesarefullyintegratedwithintheWorldBank’scountryfinancingandpolicydialogueintheenergysector.ThroughtheWorldBankGroup,ESMAPworkstoacceleratetheenergytransitionrequiredtoachieveSustainableDevelopmentGoal7(SDG7),whichensuresaccesstoaffordable,reliable,sustainable,andmodernenergyforall.IthelpsshapeWBGstrategiesandprogramstoachievetheWBGClimateChangeActionPlantargets.Learnmoreat:https://www.esmap.org.EnergySectorManagementAssistanceProgramTheWorldBank1818HStreet,N.W.Washington,DC20433USAesmap.orgesmap@worldbank.org